Ateliers of Polish painters in Munich ca. 1890

Mediathek Sorted

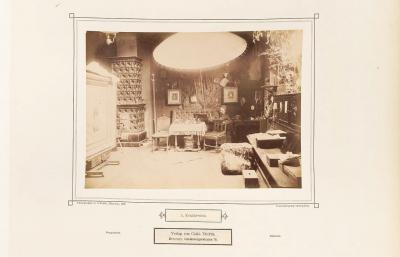

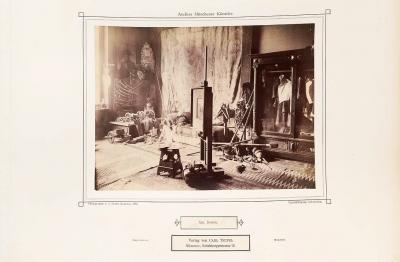

Lenbach, also a student of Piloty, had already set up a prestigious series of three rooms in his former studio that he ran from 1871 to 1886 in the atelier building of the sculptor Anton Hess (1838-1909) at Luisenstraße 17 in Maxvorstadt[17]: Whilst the first room served as the hallway, the second contained a museum-like collection with copies of Dutch and Italian paintings on walls covered with red damask. Also on display were bronze busts, carved cabinets, majolica, bear and tiger skins and antiquities “of all genres and periods”, which the artist had gathered during his trips through Europe. Only after passing through these rooms, was it possible to reach the third actual workroom, which was kept simple.[18] During his subsequent stay in Rome, Lenbach worked on a plan to build his Munich villa “as a palace which will eclipse anything that has gone before”. His historical collections were, at the highest level, to form the framework for his own works and integrate them seamlessly into the historical development of art: “There, the powerful centres of European art are to be connected with the present.”[19]

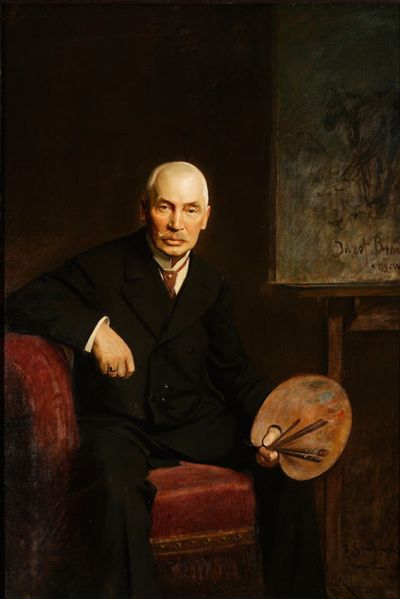

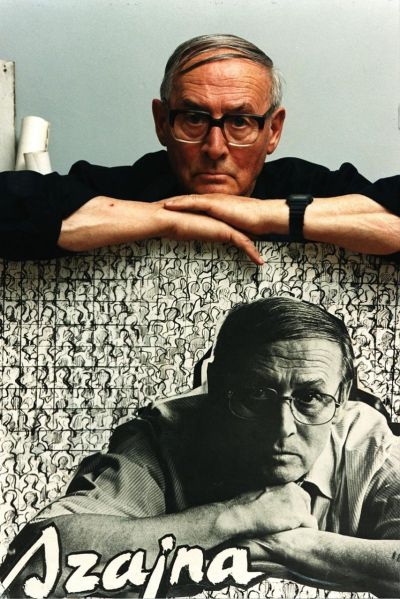

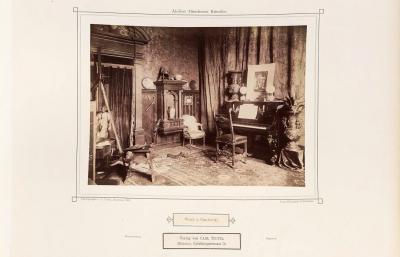

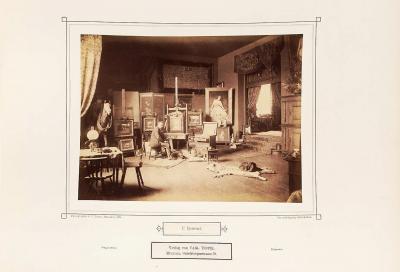

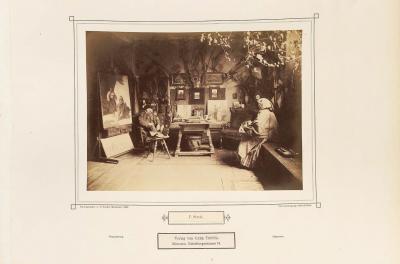

The historic artist and portrait painter Friedrich August von Kaulbach (1850-1920) set up his atelier to have a similarly high-profile. Since 1872, he had had an apartment and atelier in an apartment building at Schwanthalerstraße 36 in Ludwigsvorstadt, the rooms of which he had obviously had furnished in a stately manner. He purchased it in 1876. In 1887-89, like Lenbach, he had a villa built in the Italian Renaissance style by the architect Gabriel von Seidl (1848-1913). Whilst Lenbach’s atelier and collection were set up in an annex, Kaulbach’s atelier rooms were in the residential building where they extended across two floors over an area of 132 square metres. At the beginning of the 1890s, the studio, with its furnishing of tapestries, oriental runners, heavy materials and draperies, a coffered wooden ceiling, carved door frames, Renaissance furniture and antique sculptures, was considered the most elegant and most magnificently furnished atelier in the whole of Munich.[20] Kaulbach displayed his own paintings standing on easels and on the parquet floor along the walls. Makart in Vienna, and Lenbach and Kaulbach in Munich, but also Frederic Leighton in England, the Polish historical painter Jan Matejko in Krakow, the Hungarian Mihály Munkáczy in Paris and a generation later Franz von Stuck, again in Munich, were considered “painter princes”, not just because of their opulent artists’ residences but also because of their close ties to the ruling and royal houses and because of public homages. “Painter prince” was an unofficial and undefined title, which was actually bestowed upon Peter Paul Rubens in earlier art history and which was also applied to other artists in the late 19th century.[21]

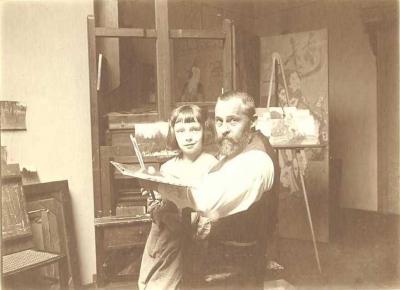

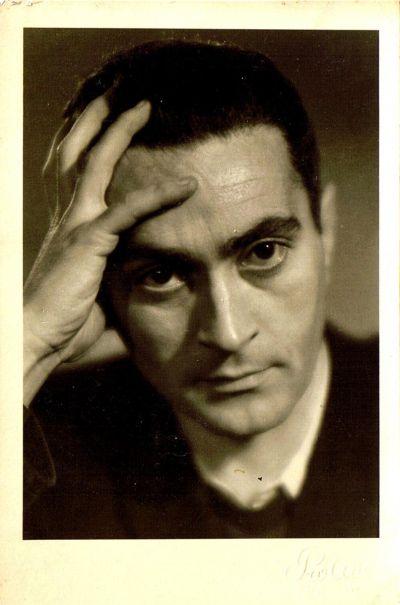

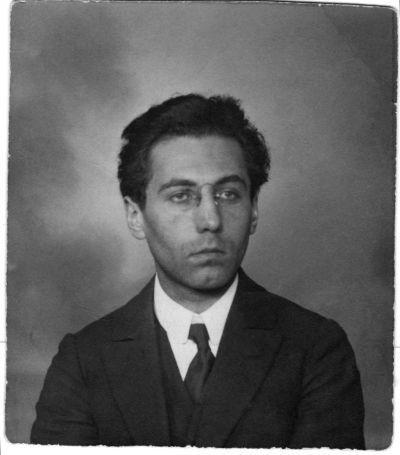

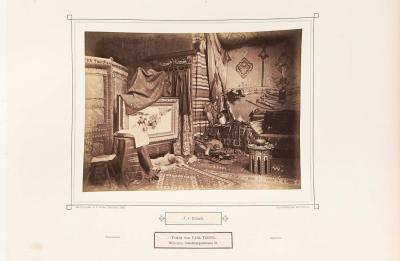

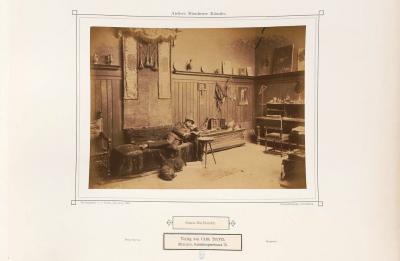

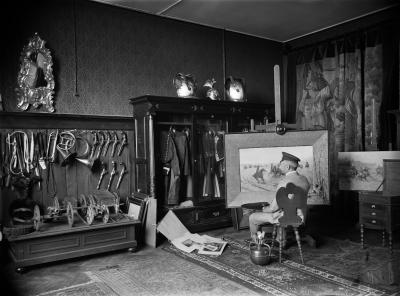

Sketched aspects and literary descriptions of the atelier of the Polish battle, equestrian and genre painter Józef Brandt (1841-1915), who called himself Josef von Brandt in Munich due to his heritage as Polish nobility, date back to the 1870s.[22] Brandt, who grew up in Warsaw, came to study in Munich via Paris in 1863. He was a year younger than Makart and, like Lenbach and Makart, studied at the Royal Academy of Visual Arts under Carl Theodor von Piloty, but mainly studied in the private atelier of the equestrian painter Franz Adam (1815-1886) and in the watercolour courses given by Theodor Horschelt (1829-1871). In 1867, he rented one of three interconnected atelier rooms at Franz Adam’s at Schillerstraße 23 in Ludwigsvorstadt. Adam taught his students, including the Polish painter Aleksander Gierymski (1850-1901), in the first room, the latter's brother Maksymilian Gierymski (1646-1874) and the Polish painter Juliusz Kossak (1824-1899), who was in Munich from 1868 to 1869, worked in the second, and Brandt did his work in the third.[23] In 1869, Brandt, who during his first year of study in Munich had already presented his works to the public there and in Krakow with tremendous success, completed his studies and went to work as a freelance artist.[24] In 1870, he moved into an apartment in the adjacent Landwehrstraße where one room served him as an atelier,[25] and in 1871 he moved one street further to Schillerstraße.[26] In 1874, Brandt rented a five-room apartment not far from Kaulbach on the second floor of an apartment building at Schwanthalerstraße 19, which he converted to meet his needs and in which he kept his atelier up until his death.[27] It is assumed that Prince Luitpold of Bavaria (1821-1912) visited Brandt’s atelier in this year. The Prince was known for his friendly association with the Munich art scene and for his visits to young artists, which were as regular as they were unannounced.[28] We can assume this because in autumn 1874, Brandt was invited to Luitpold’s for a meal at which he also met other members of the royal family.[29]

[17] Munich address book for 1878, Part III, page 82 (see online resources)

[18] Felix Gahl: Bei Franz von Lenbach, in: Der Sammler, No. 58, 1882, page 3-5; quote from Langer 1992, page 99

[19] quoted from: Franz von Lenbach 1836-1904, Exhibition Catalogue of the Municipal Art Gallery in the Lenbachhaus, Munich 1987, page 12

[20] Langer 1992, page 102-104; Birgit Joos: München – die Stadt der Malerfürsten, in: Malerfürsten 2018 (see literature), page 47; Doris H. Lehmann: Im Palast der Kunst. Bühne and Schauraum eines öffentlichen Lebens, in: Malerfürsten 2018, page 124 f. Images of Kaulbach’s atelier by an unknown photographer were published 1900 in the magazine Die Kunst für Alle, 15th Edition 1899-1900, Munich 1900, page 3 (digital reproduction: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/kfa1899_1900/0014/image); more historical photographs from Kaulbach’s atelier in the Malerfürsten exhibition catalogue 2018, page 146

[21] Birgit Jooss 2005 (see literature); Doris H. Lehmann: “Malerfürsten”. Facetten einer modernen Erfolgsgeschichte, in: Malerfürsten 2018, page 9-13. An explicit use of the term by Friedrich Pecht in an article about Makart and Lenbach’s teacher, Carl von Piloty: Ein Malerfürst der Gegenwart, in: Die Gartenlaube, No. 40, 1880, page 648-651 (digital reproduction: https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_JVxRAAAAYAAJ/page/n657)

[22] Biography of Józef Brandt in this portal in the Encyclopaedia Polonica, https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/lexikon/brandt-jozef. More information on Brandt’s ateliers can be found in the online exhibition “Józef Brandt – A Polish painter prince in Munich” in this portal, https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/Atlas-der-Erinnerungsorte/jozef-brandt

[23] Eliza Ptaszyńska 2008 (see literature), page XI; Halina Stepień: Franz Adam und sein Schülerkreis in Polen, in: Albrecht Adam and seine Familie, Exhibition catalogue of the Munich City Museum 1981/82, page 37 f.

[24] Anonymous: Art critique Die Schlacht bei Wien 1683. Oil painting by Joseph Brandt in Munich, in: Die Dioskuren, 18th Edition, No. 10, 9 March 1873, page 78

[25] Ptaszyńska 2008, page XI

[26] Munich address book for 1871, page 129

[27] Munich address book for 1875, page 126; Langer 1992, page 171

[28] Jooss 2012 (see literature), page 152, 167

[29] Ptaszyńska 2008, page XIII