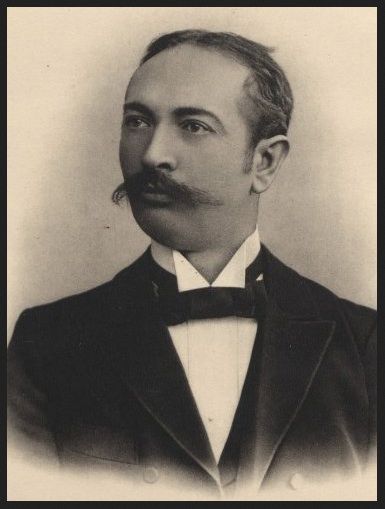

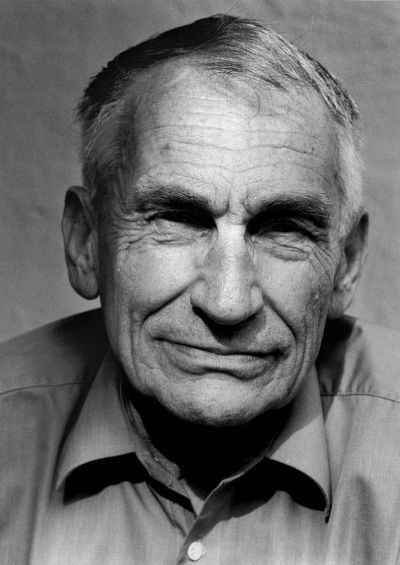

Collector, Physicist, Entrepreneur: Tomasz Niewodniczański

In the garden of his Bitburg house, Tomasz Niewodniczański had rooms built in an underground bunker to house his exhibits, creating ideal conditions for storing his collection. Along with this archive, he set up an atelier for restoring old papers and employed a curator: first Dr Peter H. Meurer, then Dr Kazimierz Kozica, who supported him in the last ten years of his life. The work of the two curators helped him to establish the collection within the scientific world. Niewodniczański published catalogues and original editions. Two volumes of the series “Cartographica Rarrissiia” (Alphen aan den Rijn) were devoted to his cartographic collection in 1992 and 1995. He visited exhibitions and conventions, supported scientific research, financially as well, in connection with objects in his collection and emerged as an author in his own right of numerous publications on the history of cartography. However, Niewodniczański was never able to complete the most prominent book project about his collection. The project involved extensive research that he had carried out in around 300 libraries and collections throughout the world over the course of 20 years working with renowned scientists. His aim was to publish a complete catalogue of cartographic representations of Poland which, alongside facsimiles and the descriptions of the maps, was to contain historical, geographical and bibliophile classification. The creators of the catalogue also wanted to provide information about maps that had supposedly not been passed down.

By acquiring manuscripts of Polish literature for his collection, Niewodniczański also brought them back into cultural circulation. The “Mickiewiczana” was published in a two-volume edition with the scientific assistance of Janusz Odrowąż-Pieniążek and Maria Danilewicz-Zielińska: “Mickiewicziana w zbiorach w Bitburgu”, (vol. I, Warsaw 1989, vol. II, Warsaw 1993). At the end of 1999, he took the initiative to publish the book “Julian Tuwim – Utwory nieznane” (Julian Tuwim. Unknown Works), which was based on the manuscripts he had acquired. Tomasz Niewodniczański was happy to have his collections on display and exhibited them on a total of 27 occasions in Holland, Spain, Germany, Poland and Lithuania. The largest exhibition with 2,272 exhibits was called “Imago Poloniae” and was held in Berlin for the first time from 2002 to 2003 and subsequently in Warsaw, Kraków and Wrocław.

In the midst of all this, Niewodniczański proved to be a generous patron transferring objects from his collection to the organisers of the exhibitions. In 1998, he gave the Uniwersytet Szczeciński (Szczecin University) 100 historical maps of Pomerania from the 16th and 19th century and around 200 views of Szczecin and towns from the region. In 2002, he gave 200 old maps and views of Silesia to the Ossolineum in Wrocław (Ossolinski National Library in Wrocław).

In the final years of his life, whilst pondering the future of his treasures, Dr Niewodniczański announced that he would be donating his collection of Polish memorabilia to museums in Poland, under the condition, however, that the Republic of Poland returned the so-called”Berlinka” collection to the State Library of Prussian Cultural Heritage. This collection, along with manuscripts from Goethe and Mozart, had found their way to Poland in all the confusion of the Second World War.[10] He broadened this proposal by asking the Germans to set up a foundation with a capital of 300 to 400 million euros to acquire any Polish memorabilia offered at auctions around the world for Polish museums. Whilst this idea was debated by the Polish and German media, it did not actually come into fruition.

Because of this, Tomasz Niewodniczański changed his instructions once more before his death. He realised his dream and handed over the lion’s share of his Polish memorabilia to the Royal Palace in Warsaw on permanent loan . The collection included around 2,500 maps, 40 Polish atlases, around 150 cityscapes, royal facsimiles, 900 old prints, around 4,700 historical and literary autographs and signed books of renowned authors. The rest of the collection remained in the Niewodniczański family.

[10] The State Library of Prussian Cultural Heritage is the successor to the State Library of Prussia.