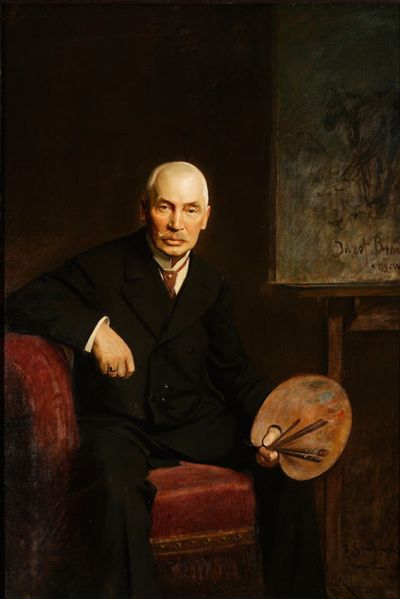

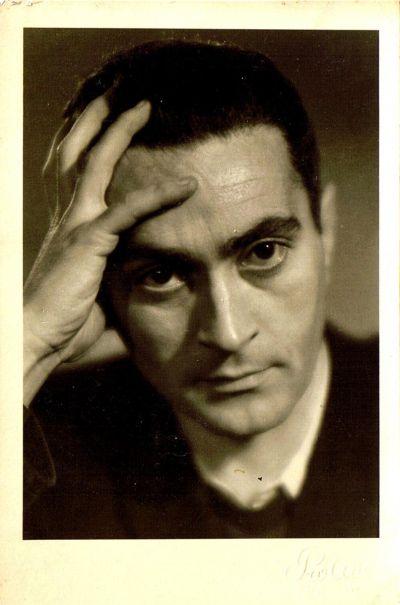

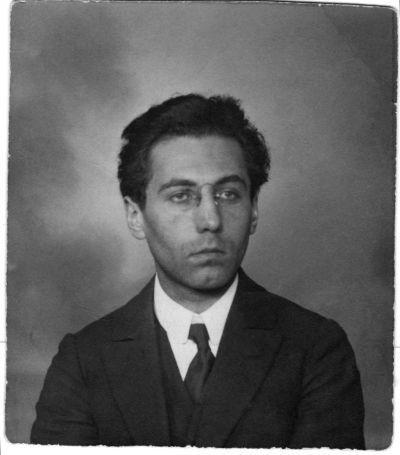

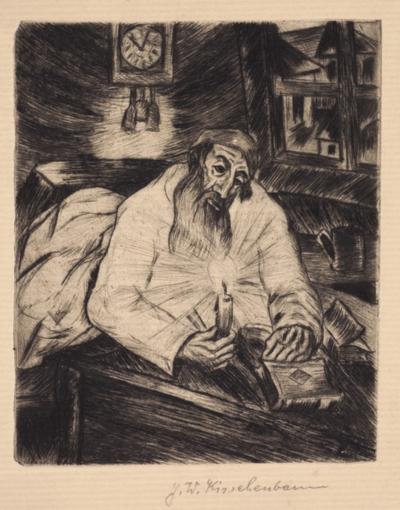

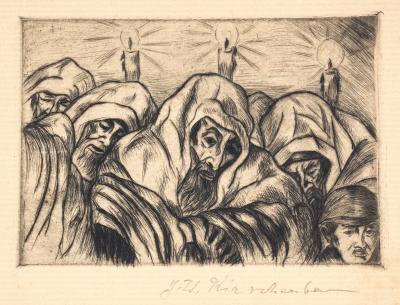

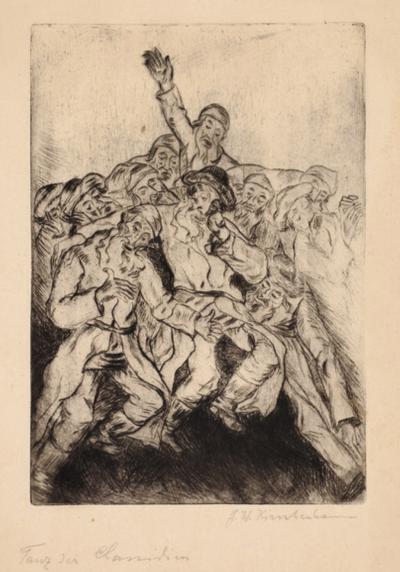

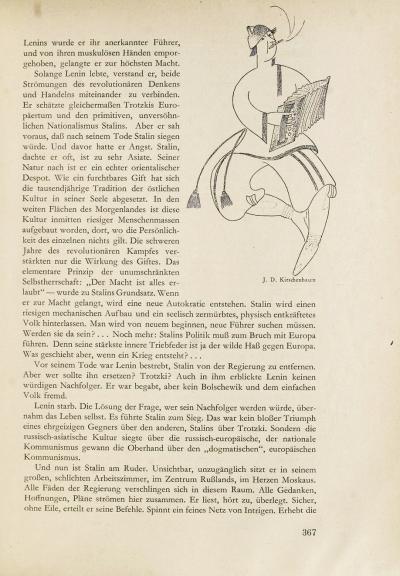

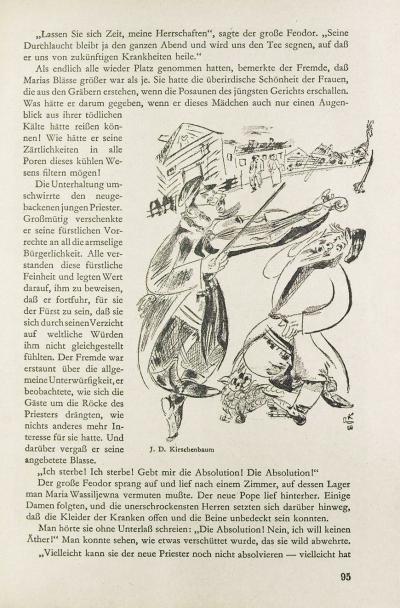

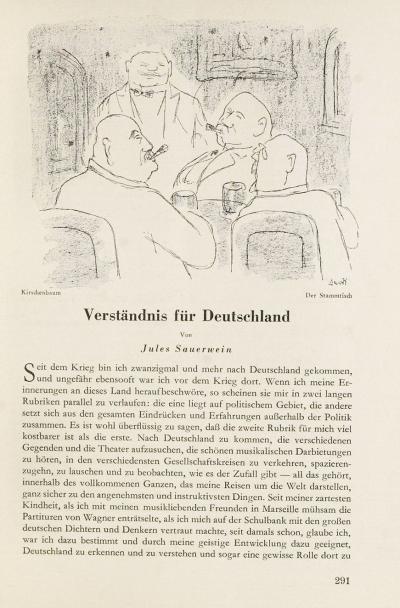

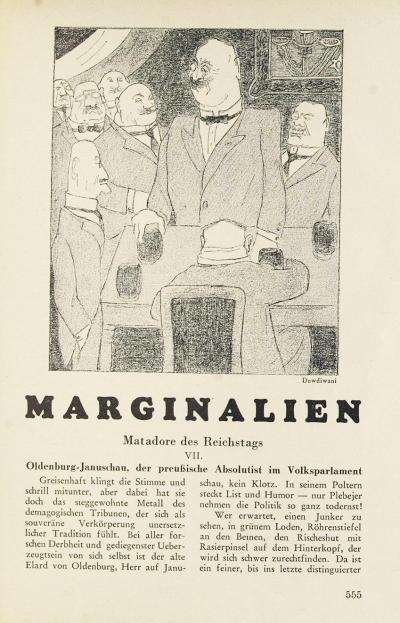

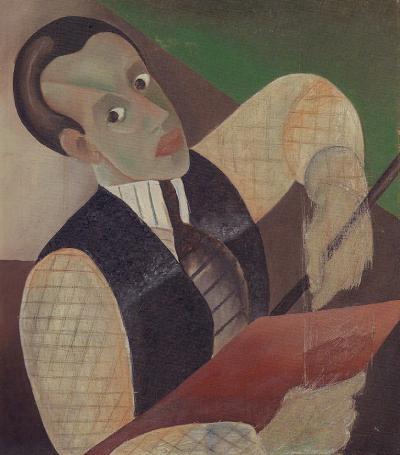

Jesekiel David Kirszenbaum (1900–1954). Student of the Bauhaus

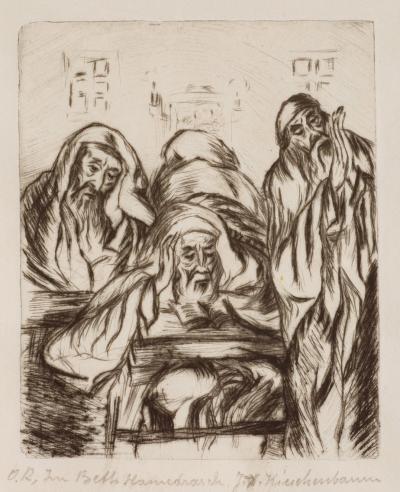

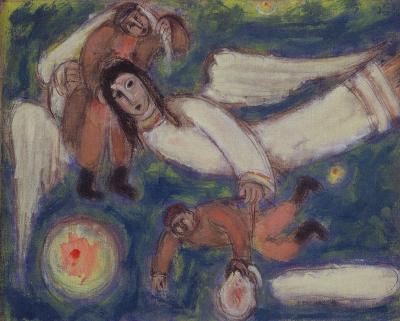

“What other children were allowed to do, was off limits for me”, writes Kirszenbaum in his memoirs about his childhood and youth in Staszów.[1] As the youngest child of the rabbi Natan Majer Kirszenbaum and his wife Alta, née Ledermann, his calling was to be a rabbi, so it was not becoming for him to take part in the other children’s games. In the Cheder, the religious primary school, his interest was awakened by the fantastically embellished stories of the Chumasch, the five printed books of the Tora, and the folk legends in the Sefer ha-Jaschar, the mediaeval Book of Jashar, whilst the Talmud and its commentaries bored him. He lived in a dream world and longed for stories full of imagination and creativity. After he lost both his older brothers to illness at the age of 10 and 13, his parents started to embrace fanatical religious beliefs whilst he lay in the meadow, daydreaming and thinking about things that only existed in his sub-conscious, instead of immersing himself in the Talmud in the Beth Midrasch, the study room.

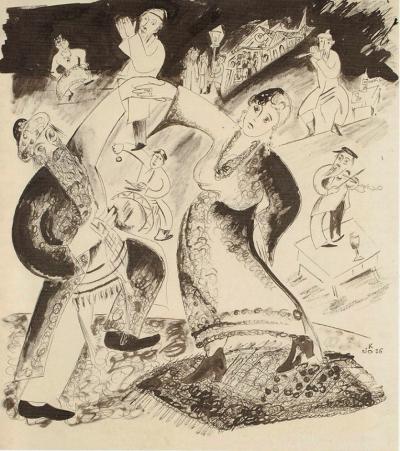

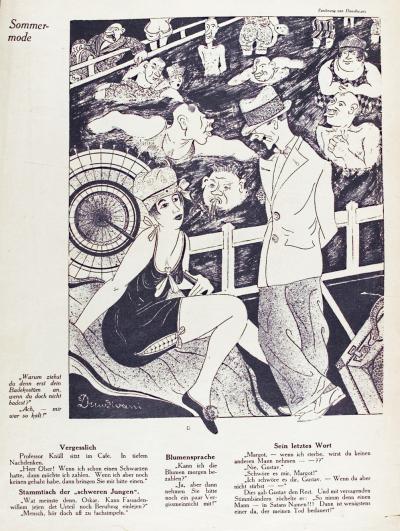

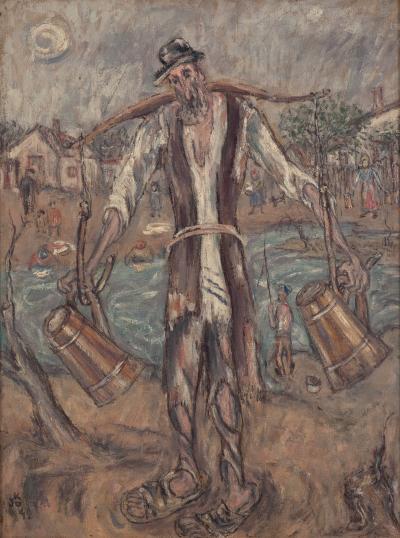

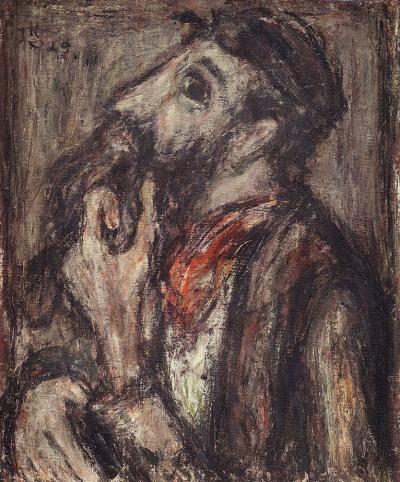

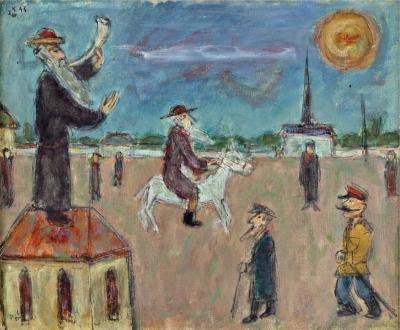

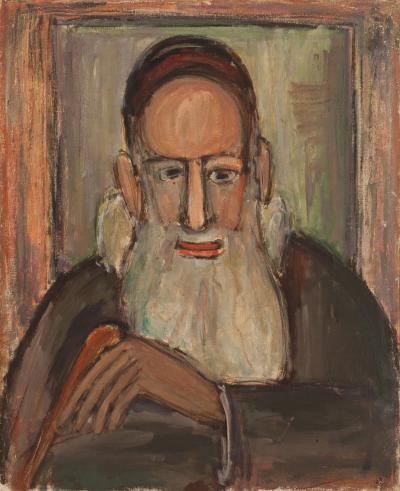

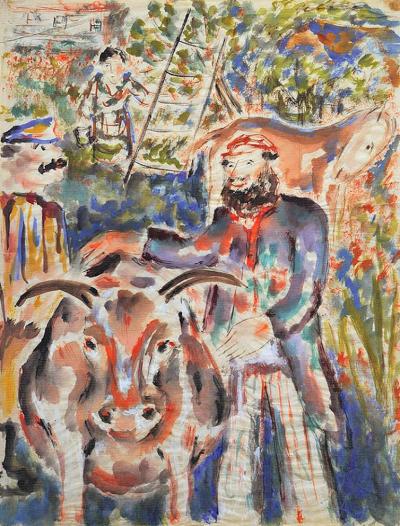

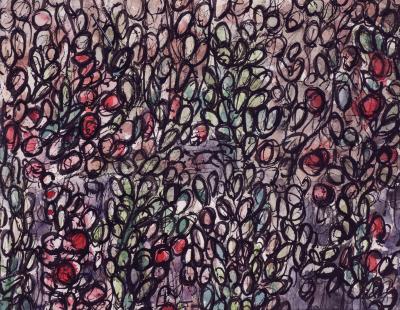

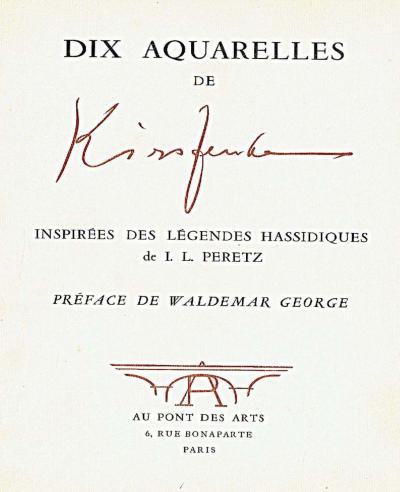

What made him happy was the way of life of the simple Jewish people, the wandering musicians with their parrots who played at the Jewish festivals, and the load carriers and water carriers with their colourful robes. He felt the urge to draw, especially portraits, which was forbidden because of the Jewish prohibition on representing living forms in images, and for which he was hit by his father. In Staszów during the First World War he experienced at first hand the Cossacks passing through his village and the Jewish pogrom. He also saw Austrian and German troops, plundering and murdering Tsarists, who took Jews away with them. When he was sixteen or seventeen, he began to read classic Yiddish authors like Jizchok Leib Perez (I.L. Peretz) and Spinoza and became an Epikoros, a critic of the Jewish religion. He hung around with his friends and with girls, became a member of the socialist-zionist Hashomer-Hatzair youth movement, was hit by his parents again and fled to relatives in the neighbouring village.

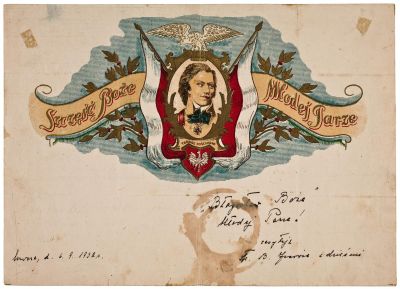

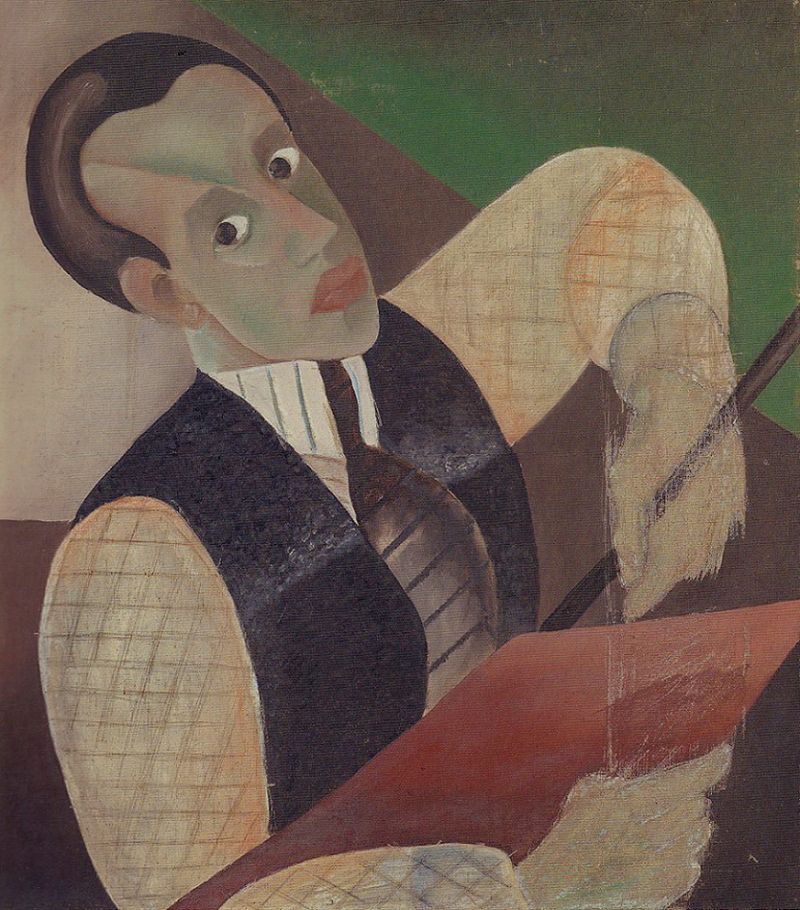

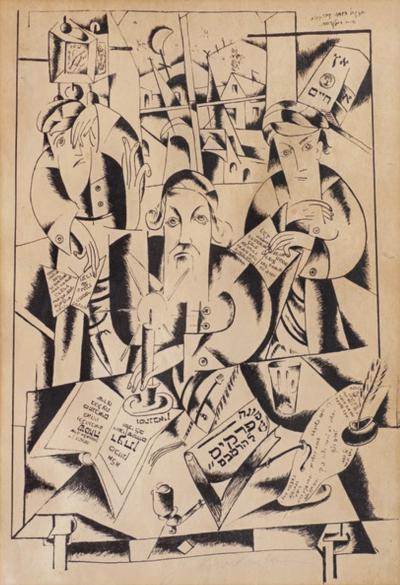

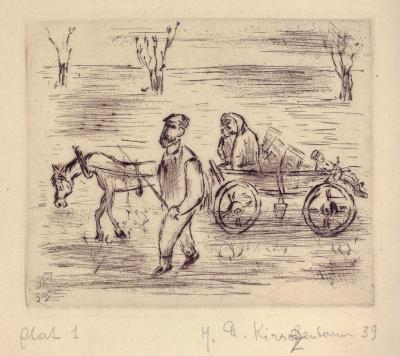

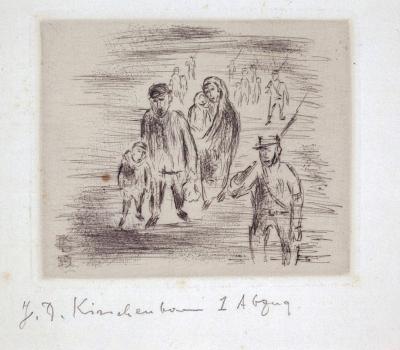

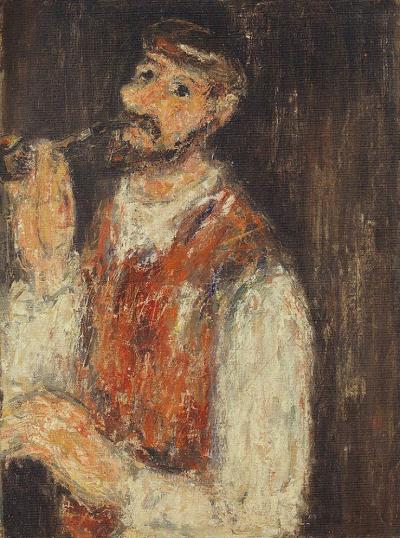

Having returned to his parents, he started reading books and drawing again. His portraits of Jewish ideologists Theodor Herzl, Karl Marx and Wladimir Medem hung in the clubs in Staszów and the surrounding towns, and his portraits of Yiddish authors Mendele Moicher Sforim, Scholem Alejchem and Perez hung in the local library (Fig. 1).[2] He made a second attempt to escape with the intention of studying art in Krakow, but failed because of his lack of money and education. When he returned home again, his relationship with his parents improved. In 1920, when he was due to be drafted into the Polish army during the Polish-Soviet war, he sold everything he owned to finance his journey to Będzin[3] on the border with Upper Silesia in Prussia and then his escape to Germany.

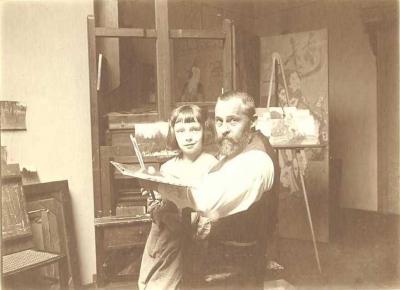

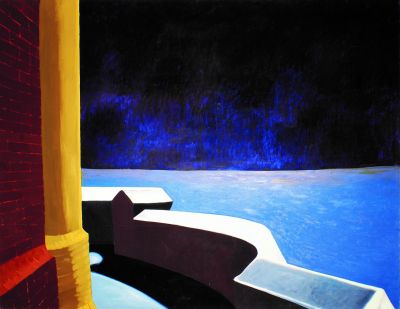

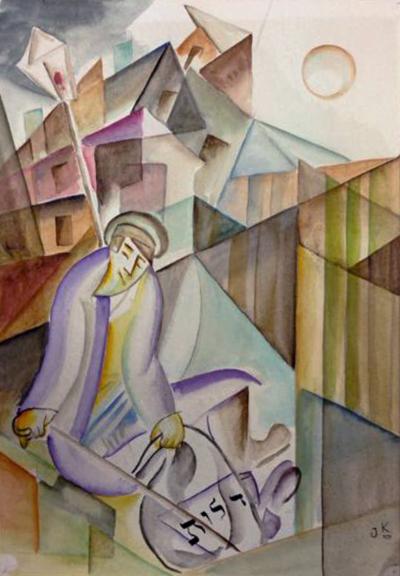

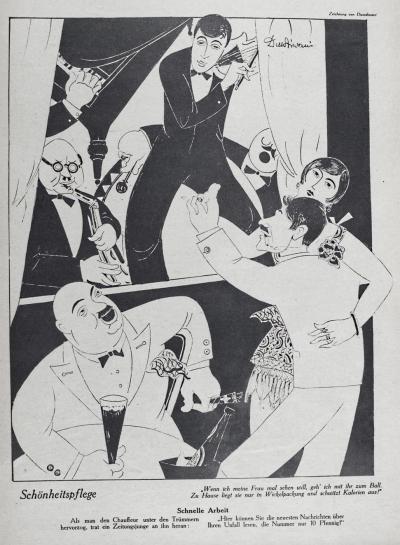

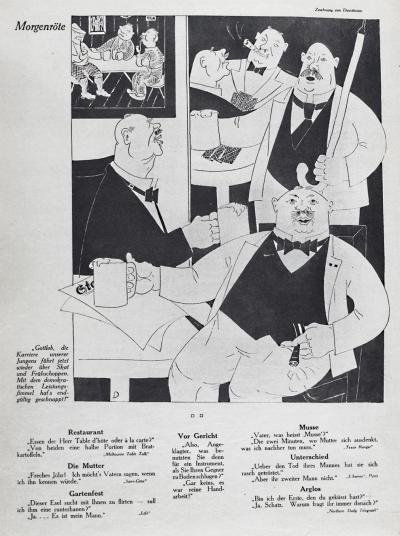

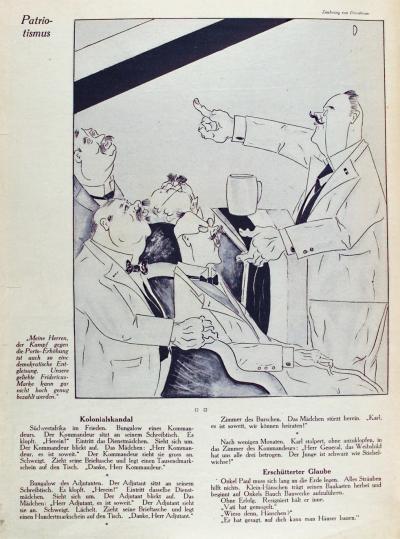

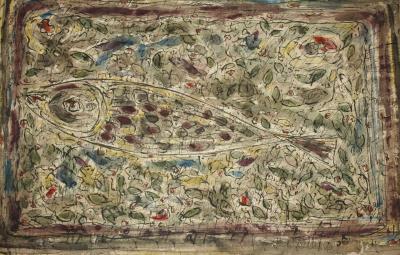

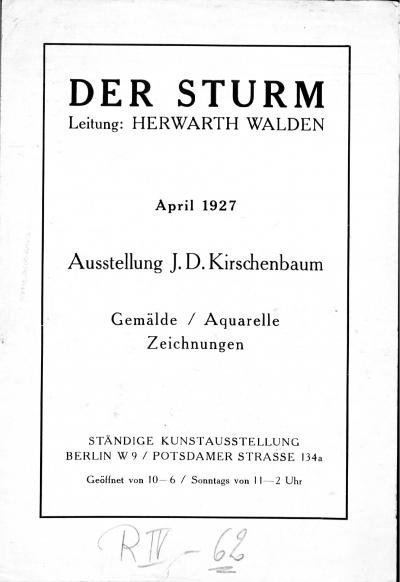

It is not known how exactly Kirszenbaum finally arrived in the Ruhr region. Like more than half a million Ruhr Poles who had emigrated there since the foundation of the German Reich, he earnt his money as a mine worker and from 1920 lived as a tenant in Duisburg, as evidenced by a postcard to his family[4]. He gave Hebrew lessons on the side, but must also have been working as an artist. The art historian August Hoff (1892-1971), who later became the director of the Duisburg Museum of Art/Duisburg Kunstmuseum, became aware of Kirszenbaum, urged him to study art and apparently found him a place at the State Bauhaus/Staatliche Bauhaus in Weimar. Kirszenbaum began his studies there in 1923 in the preliminary course given by Johannes Itten and, during the following three semesters, also attended courses given by Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee. He later wrote that Kandinsky and his clarity of thought had had the greatest influence on him. In particular, Kandinsky moved him from a formalistic style of painting to figurative painting, in contrast to his own artistic interests.[5] He is said to have maintained a collegial connection to Klee. Klee influenced him with his “inner world” and the diversity and endlessness of his dream images.[6] When political pressure meant that the Bauhaus was closed down at the turn of 1924/25 and moved to Dessau, Kandinsky is said to have earmarked him for a lecturing post at the new site, which ultimately failed to transpire following opposition from the Director, Walter Gropius.[7]

[1] Jechezkiel Kirszenbaum: Childhood and Youth in Staszów, in: J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see Literature), page 129

[2] ibid., page 155

[3] ibid., page 167 f.

[4] J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see Literature), page 49

[5] ibid., page 48

[6] ibid., page 49

[7] Linsler 2013 (see Literature), page 293. Linsler refers to an essay by Ernst Collin: J.D. Kirschenbaum, in: Exhibition Catalogue from Galerie Fritz Weber, Berlin 1931 [Bauhaus Archive, Inv. No. 2239], to an essay by Frédéric Hagen: J.D. Kirszenbaum = Exhibition Catalogue from Galerie Karl Flinker, Paris 1961, and to the article by Hanna Bartnicka-Górska: Jecheskiel Dawid Kirszenbaum, in: Słownik Artystów Polskich i obcych w polsce działających. Malarze rzeżbiarze graficy, 3, Polska Akademia Nauk, Instytut Sztuki, Warsaw 1979, page 412. Ernst Collin (1886-1942 murdered in Auschwitz) was a bookbinder, author, art editor and antiquarian from Berlin, see https://www.stolpersteine-berlin.de/de/biografie/6661. See below for more on Frédéric (Friedrich) Hagen.