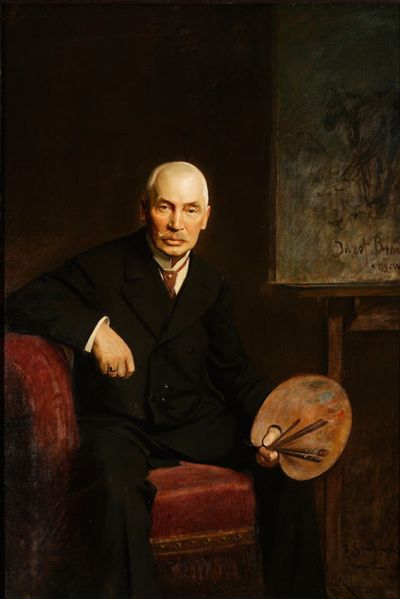

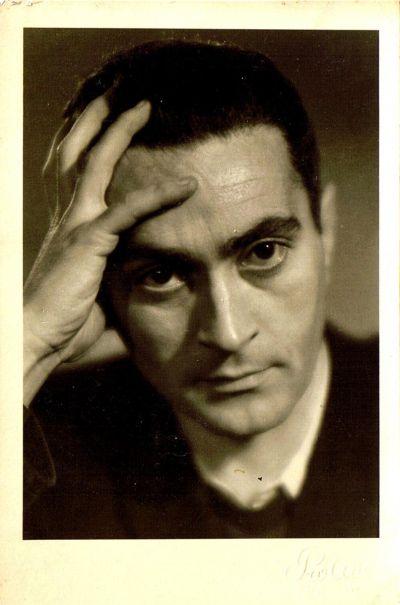

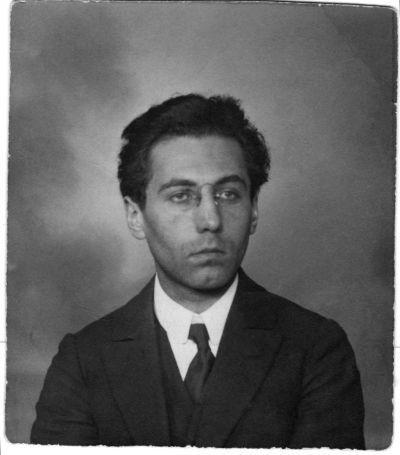

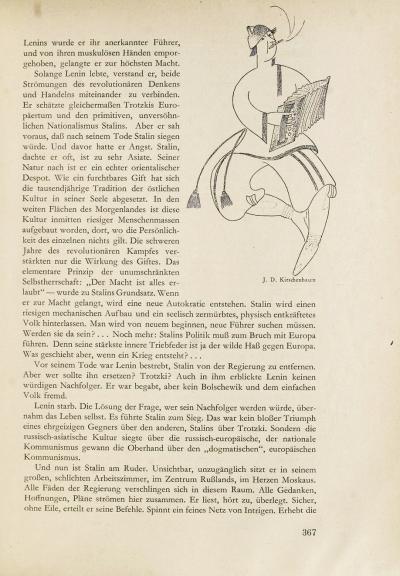

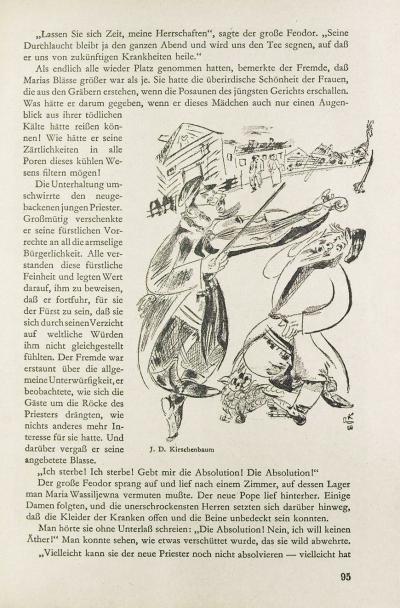

Jesekiel David Kirszenbaum (1900–1954). Student of the Bauhaus

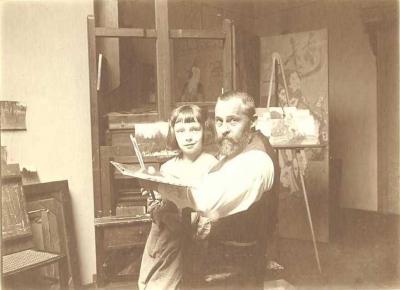

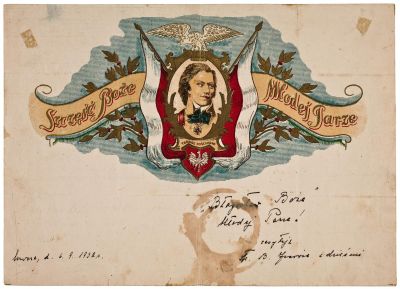

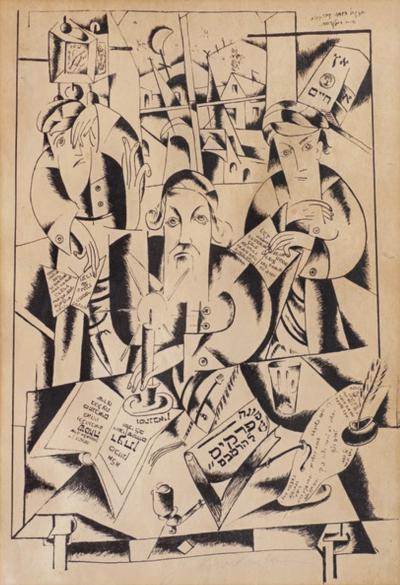

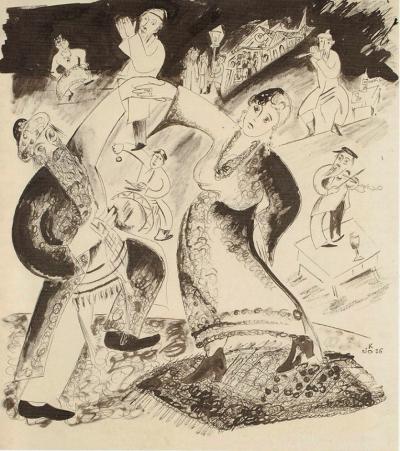

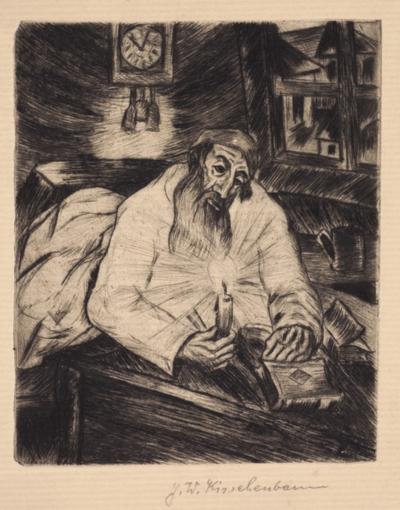

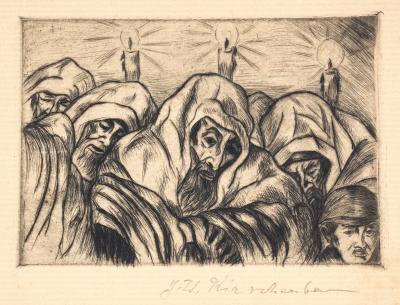

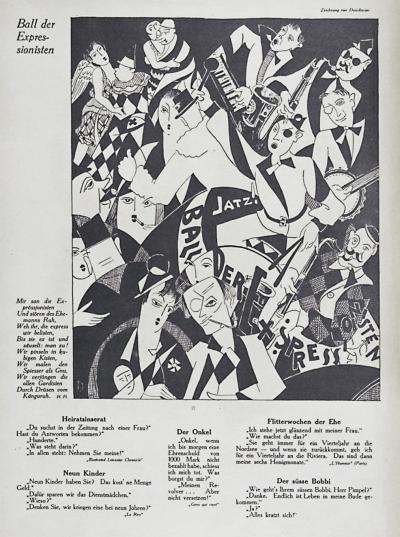

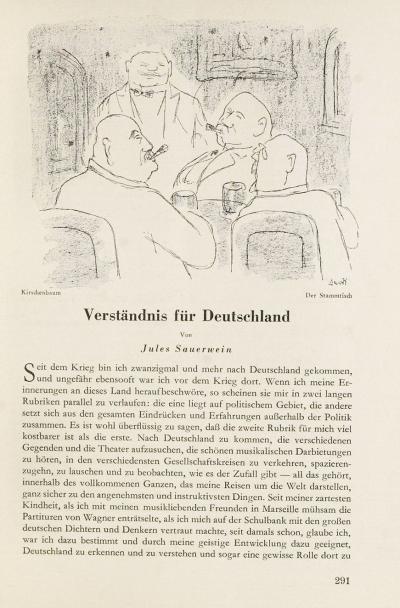

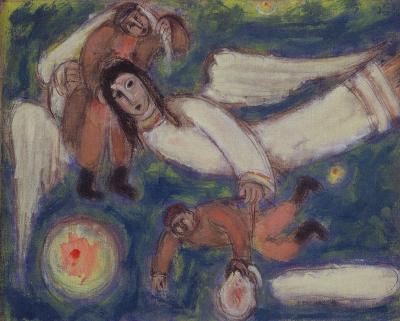

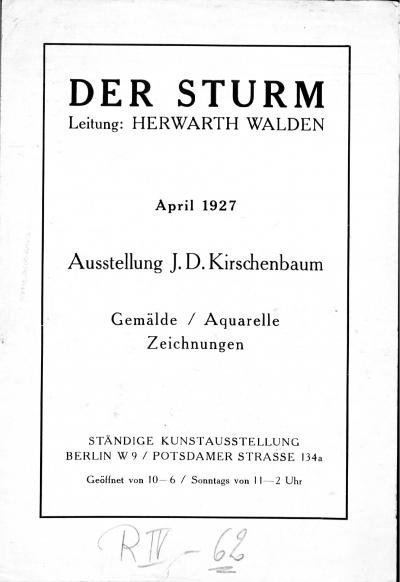

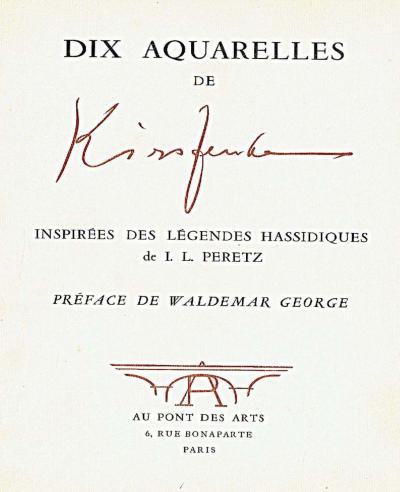

“Studying the Maïmonide” (Fig. 2) and “Musicians and their disciples” (Fig. 3), two ink drawings produced in Berlin in 1925 directly after Kirszenbaum’s studies at the Bauhaus, reflect, with their two-dimensional style, overlapping geometric and prismatic shapes and the introduction of written elements, art movements of the time between cubism, Dadaism and expressionism. It is possible that they were intended as templates for woodcuts and linocuts, like the high-contrast monochrome ones created by a number of artists at this time as illustrations and graphic supplements for magazines, such as the Sturm. The motifs reflect everyday scenes from the shtetl, which Kirszenbaum had experienced in his youth and childhood in Staszów and which he described in his written memoirs: studying the old Jewish scriptures in the Cheder, and the traditional fiddlers whose music brought together townsfolk and animals alike, recalling similar motifs by Chagall.

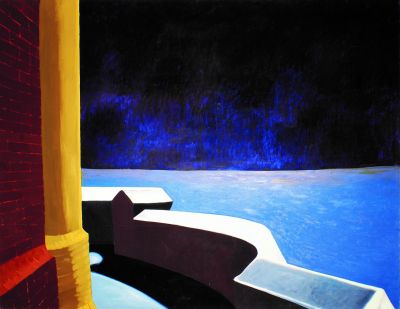

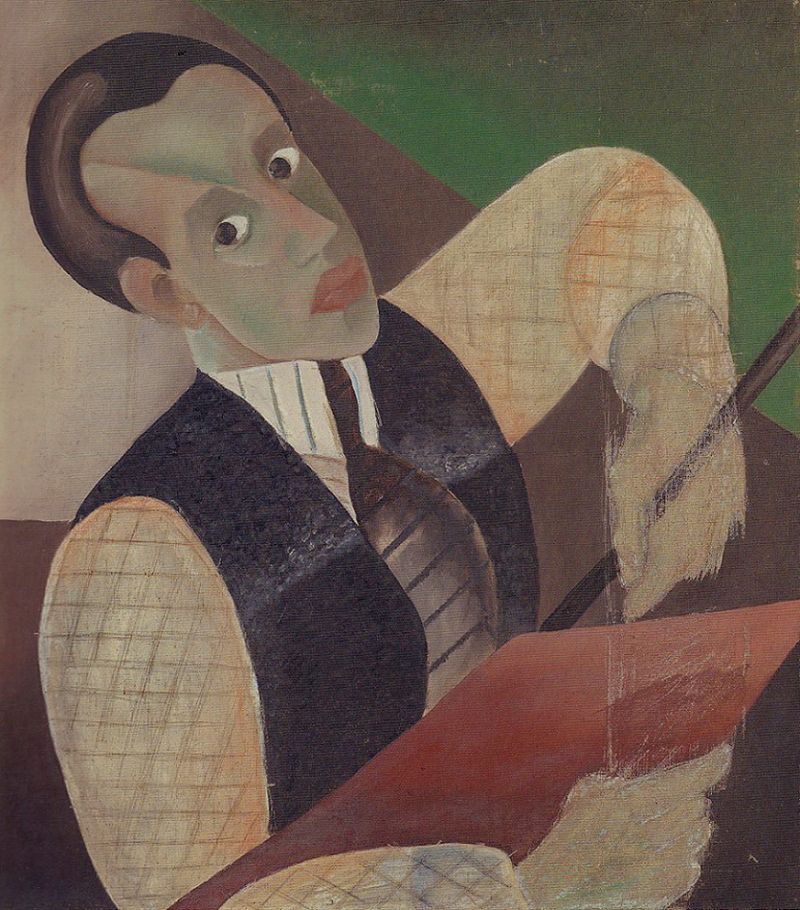

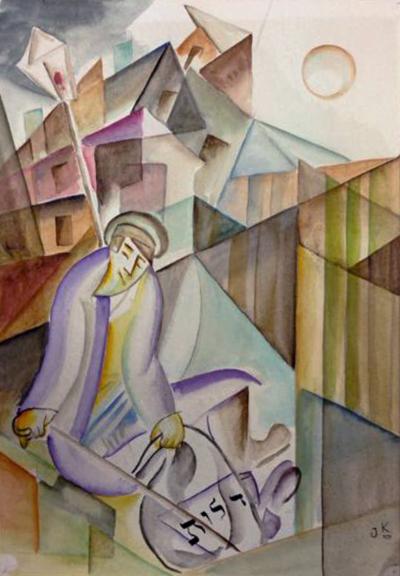

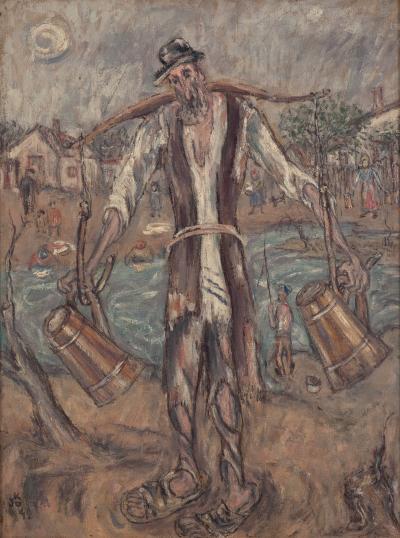

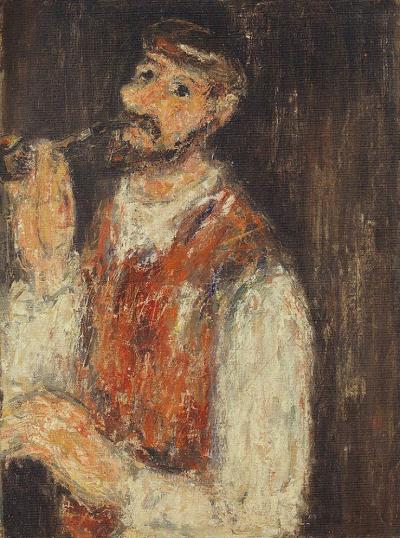

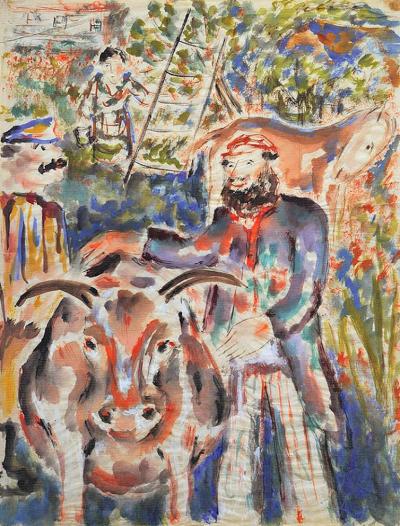

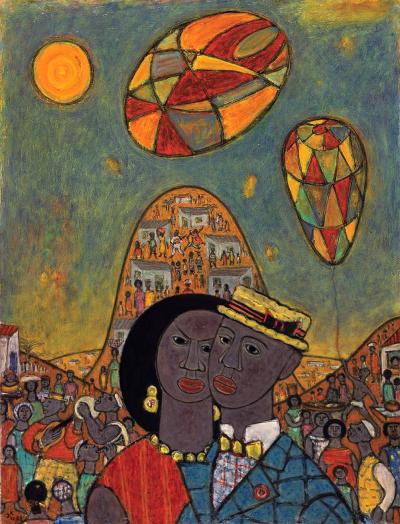

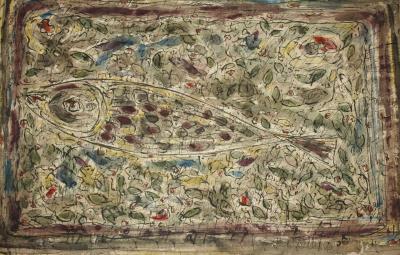

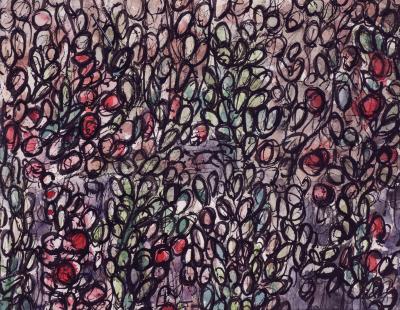

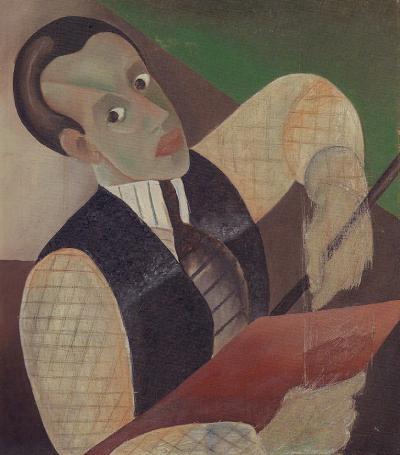

The geometric segmenting of the figures and the schematised physiognomies of the “musicians” (Fig. 3) recall the early work of Chagall, such as his “The cattle dealer” from 1912: sold by the Sturm publishing house as an art postcard and still depicted by Walden in a written defence of expressionism as late as April 1926.[49] In the “Maïmonide” work (Fig. 2), a prismatically blended cityscape, like the one created in 1922 in “Mellingen VI” by Lyonel Feininger, head of the printing workshops at the Bauhaus, appears in the view through the back window.[50] Kirszenbaum’s watercolour “Sorrow”, painted around 1925, is reminiscent of Feininger, but also of the prismatic shapes of the “Monument to the March Dead” in the main cemetery in Weimar created in 1922 by Walter Gropius, the director of the Bauhaus (Fig. 4). The painting “Fiddler in the shtetl” (Fig. 5), prepared in the cubist style as a motif in Chagall’s early work,[51] but also described in Kirszenbaum’s written memories of childhood,[52] sets the tone for his late-impressionist style of the thirties and forties (Fig. 38, 42).

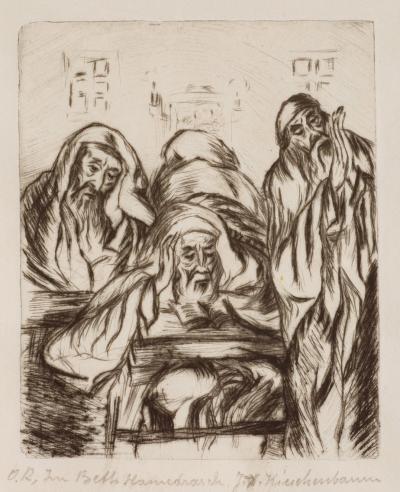

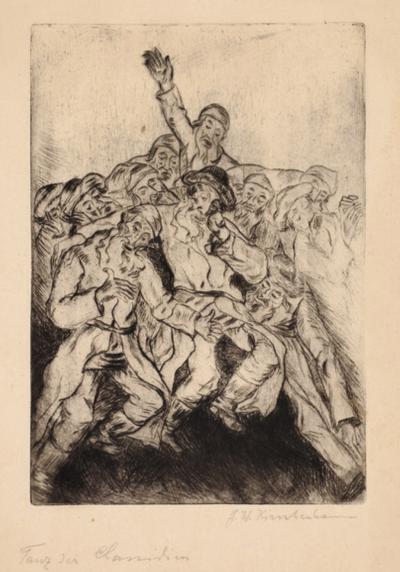

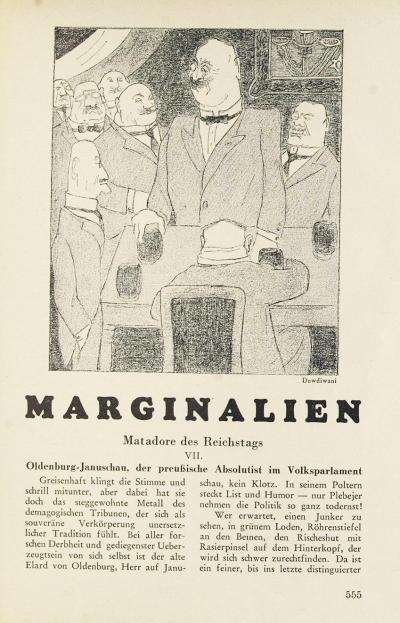

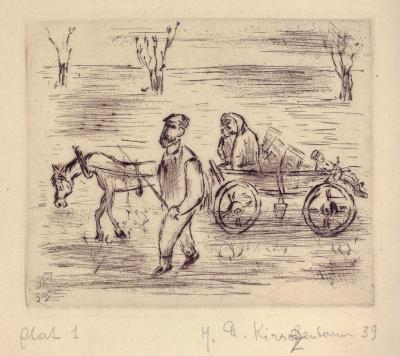

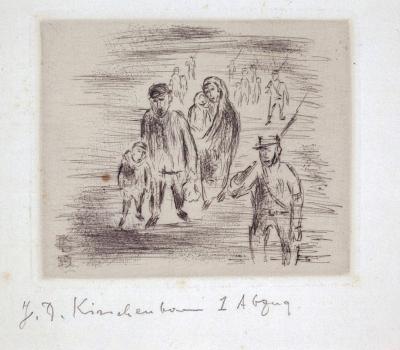

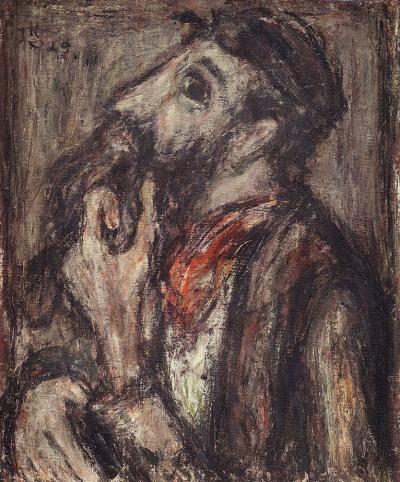

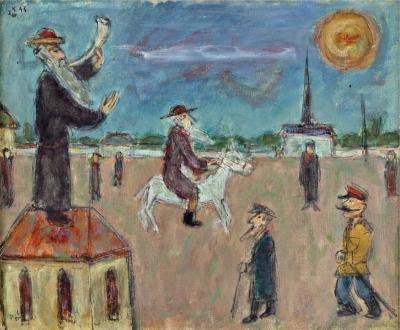

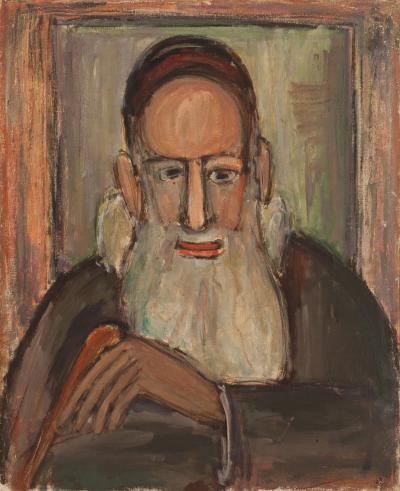

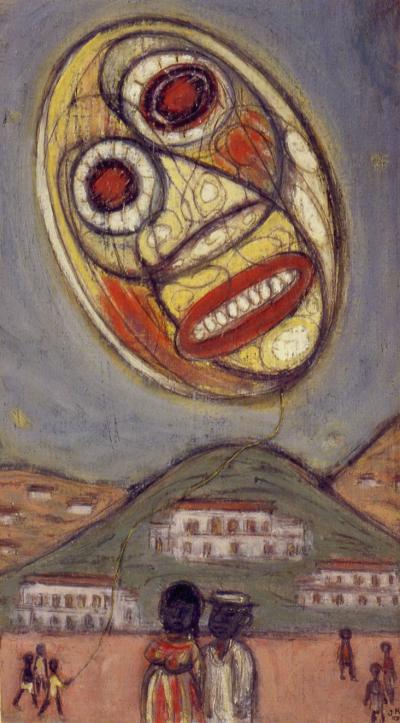

A drawing and etchings with scenes from Jewish life (Fig. 6-11), which follow the two earliest known motifs of this kind from 1923, are very different in character. With its scattered little figures, “The Wedding” (1925, Fig. 6), an ink drawing owned by the Jewish Historical Institute/Jüdischen Historischen Instituts in Warsaw, follows the stylised, light-hearted style favoured by Chagall in his etchings around 1925[53] which became characteristic of his later work. The sharp-edged expressionist scenes with faces of praying Jews visibly moved (Fig. 7-9) recall similar heads and similar scenes by Ludwig Meidner (1884-1966) and Jakob Steinhardt (1887-1968), who both belonged to the group of Berlin Sturm artists and who are both known for their Jewish motifs. The influence of these two artists is particularly visible in Kirszenbaum’s motional scenes, “Dance of the Hassidim“, (1925, Fig. 10) and “Pogrom by the Cossacks” (ca. 1930, Fig. 11).

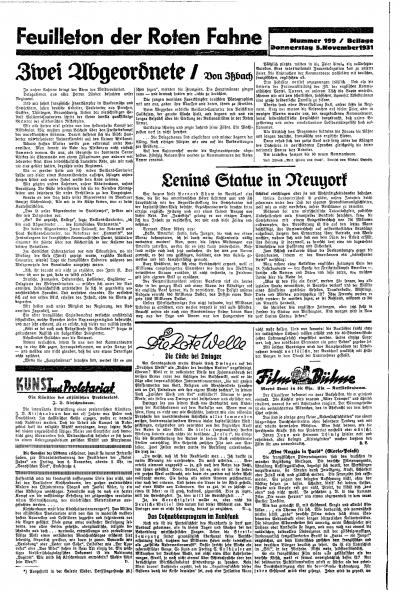

Also known for his Jewish motifs was the painter Issachar Ber Ryback (1897-1935). Originally from the Ukraine but living in Berlin from 1921, he belonged to the November Group, showed his works in the Juryfreie Kunstaustellung and went to Paris in 1926. He also produced numerous versions of a fiddler in the shtetl and other traditional folk scenes. It is fair to assume that during his time in Berlin, Kirszenbaum moved increasingly within the circle of Jewish artists, including Paul Citroen, where he was able to make a name for himself with the scenes he produced. Also documented is Kirszenbaum’s friendship with the Jewish painter Felix Nussbaum (1904-1944 murdered in Auschwitz), who studied at the Lewin-Funcke-Schule in Berlin from 1923, was ranked amongst the successful young Berlin artists from 1930/31, and in 1933 emigrated via Italy and France to Belgium.[54] In 1931, Nussbaum took part in the Women in Need/Frauen in Not exhibition.[55]

[49] Herwarth Walden: Expressionism, in: Der Sturm, 17th Edition, 1st Issue, Berlin, April 1926, pages 2-12, Marc Chagall: The Cattle Dealer, page 5, https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/sturm1926_1927/0013/image. Today, the painting can be found in the Basel Museum of Art/Kunstmuseum Basel, http://sammlungonline.kunstmuseumbasel.ch/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=1129&viewType=detailView

[50] Depicted in the catalogue accompanying the Bauhaus Exhibition of 1923: State Bauhaus Weimar 1919-1923, Weimar, Munich, 1923, page 183. Today the painting can be found in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, https://www.imj.org.il/en/collections/387956

[51] Marc Chagall: “The Violinist”, 1912/13, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, https://www.stedelijk.nl/en/collection/753-marc-chagall-le-violoniste; a wood or lino cut by Chagall with a violin in front of the shtetl depicted in 1917 in: Der Sturm, 8th Edition, 2nd Issue, Berlin, May 1917, page 25, online resource https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/sturm1917_1918/0031/image

[52] “The blind violinist would come to Staszów each year right before Pesach; he was the herald of spring in Staszów. The piercing strings of his violin would express boundless sadness, and when he would accompany his playing with a song on the pogrom in Kishinev, the whole picture of the terrifying events would be visible before my eyes.” (J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013, see Literature, page 129)

[53] Marc Chagall: Acrobat with the violin, 1924, etching and drypoint; illustrations for Nikolai Gogol, Dead Souls, 1923-27, etchings (Marc Chagall. Graphic print, published by Ernst-Gerhard Güse, Stuttgart 1985, page 247, 46-73)

[54] Around the turn of 1946/47, Kirszenbaum enquired about the fate of Felix Nussbaum in a letter to the Director of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, Paul Fieren, and on 20 January 1947 received the response that Nussbaum and his wife had been deported to a concentration camp and had not returned. (Letter pictured in J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013, see Literature, page 26 f.)

[55] Adolf Behne: The “Women in Need” exhibition, in: Welt am Abend, No. 243, 1931; depicted in: Revolution and Realism 1978 (see Literature), page 28