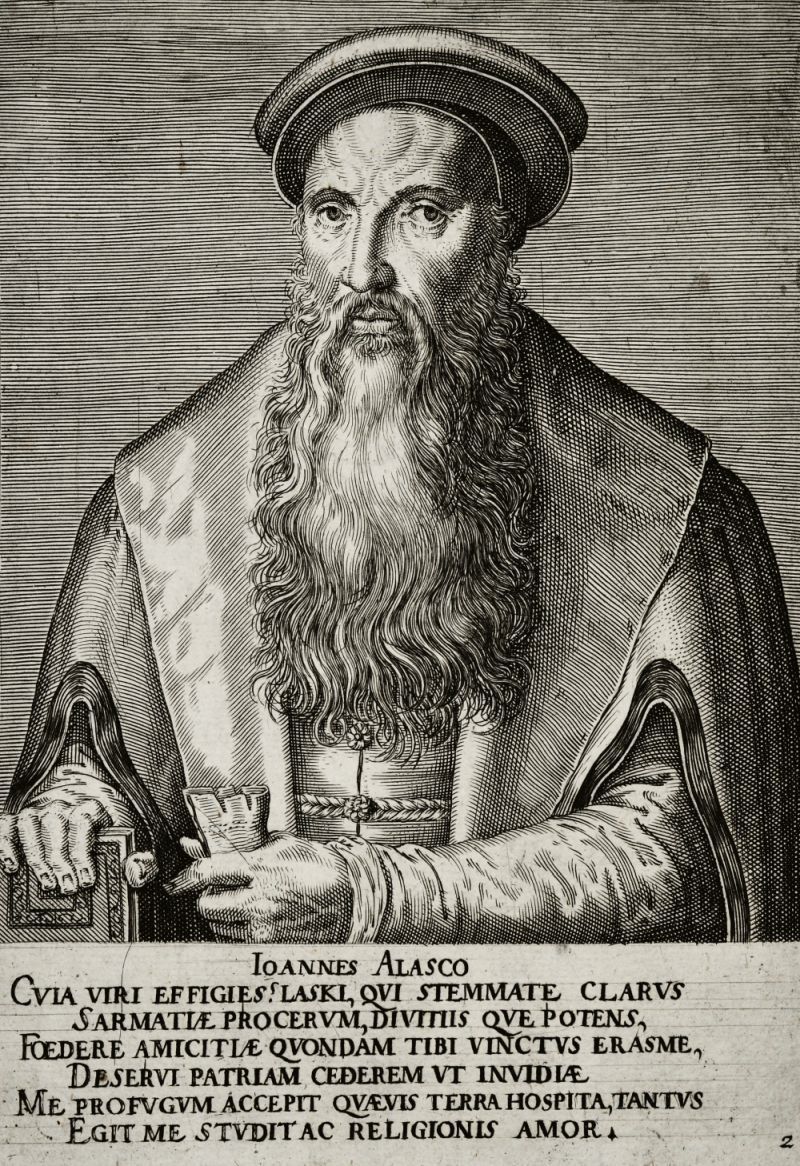

Johannes a Lasco

Mediathek Sorted

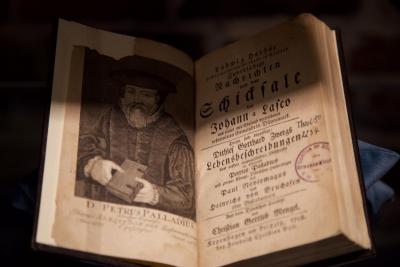

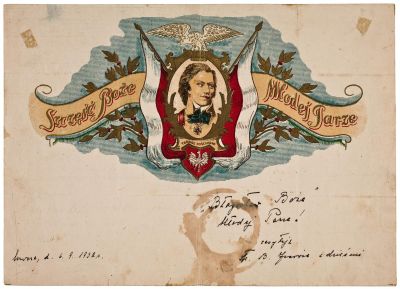

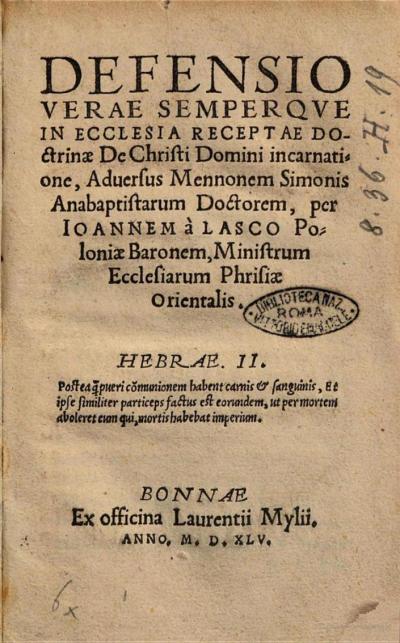

To differentiate the Protestant church from the Catholics and the Baptists, à Lasco chose disputation, a common measure of the time, which involved scholarly debate, in which the participants, based on the Bible, were supposed to provide evidence of the correctness of their belief and their teaching. The Catholic monks avoided these discussions and, as a result, were no longer allowed to preach or baptise. During the course of the 16th century they left East Frisia. In January 1544, a religious discussion of this kind was held with the Baptists, in particular Menno Simons (1496-1561), in which the aim was to reach a consensus about the original sin and the doctrine of justification, that is to say, the question of whether the justification of the sinner before God can be achieved by good deeds or merely through belief; no agreement could be reached about the incarnation of Christ and the offices of the church. However, the parties parted amicably. Menno left Emden a few months later and went to Cologne; however, large numbers of his followers, who at this time were already called “Mennonites”, remained in East Frisia. In 1545, à Lasco wrote a paper in which he defended his views on the incarnation of Christ against those of Menno (Fig. 1).[17] No agreement was reached with David Joris (1501/02-1556), the leader of the mystic-spiritualist school of thought among the Baptists. Instead of having all Baptists expelled from East Frisia, à Lasco embarked on difficult and time-consuming discussions with each of the religious refugees arriving from the Netherlands.

As organisational measures intended to stabilise the East Frisian church, à Lasco instigated the founding of a Church Council for each congregation and the church discipline for the members of the congregation and ordered all images, altars and Catholic requisites to be removed from the churches. The Church Council, which he introduced around the turn of the year 1543/44 for the Great Church in Emden, was made up of the preachers and four Elders elected from the congregation. The Church Council exerted church discipline on the members of the congregation, a discipline which demanded good behaviour in daily life, in marriage, towards neighbours and proper housekeeping. For anyone who was drunk, swore in public or committed other nuisances, the Church Council could impose penalties or exclusion from the Eucharist as a punishment. A Lasco managed to convince Countess Anna to abolish idolatry, i.e. image veneration, and, consequently, she had the majority of religious images and objects removed from the Great Church. He made sure that these measures were enforced in rural congregations by visitations, i.e. by personal visits to the village churches and their preachers.[18]

As a further step towards unification, à Lasco created “Coetus” (lat. assembly), a weekly meeting of preachers which took place in Emden in the summer half-year and at which theological issues were discussed. The suitability, teaching and lifestyle of newly arrived theologians were examined in mutual discussions. Using a compromise formula, the “moderatio doctrinae”, à Lasco attempted to emphasise the commonalities and to push back on the contentious questions, such as the dispute about the Eucharist, which was the problem discussed among the Reformers, Luther’s followers and Zwingli’s followers as to how Christ’s presence in the Eucharist was to be considered. However, the differences, particularly between the Reformers and the Lutherans, were so severe that the Coetus in its original form collapsed and only survived as a meeting of Reformist preachers, which still exists today. According to Jürgens, à Lasco, who corresponded with leading theologians of his time, such as Melanchthon, proved overall “to be less the profound theologian […], and more the capable organiser, who created functional and lasting committees and councils”.[19]

[17] Defensio verae semperque in ecclesia receptae doctrinae de Christi Domini incarnatione, adversus Mennonem Simonis …, Bonn 1545, Johannes à Lasco Bibliothek**, Emden; Jürgens 1999 (see Bibliography 2.), p. 54 f.

[18] Jürgens 1999 (see Bibliography 1.), p. 25-28; Jürgens 2002 (see Bibliography 3.), p. 222-303

[19] Jürgens 1999 (see Bibliography 1.), p. 29

![Fig. 4: Response to Joachim Westphal, 1560 Fig. 4: Response to Joachim Westphal, 1560 - John à Lasco/Jan Łaski: Responsio ad uirule[n]tam, calumniisque Ac Mendaciis Consarcinatam hominis furiosi Ioachimi VVestphali Epistola[m] quandam, qua purgationem Ecclesiaru[m] Peregrinarum Francoforti conuellere conatur, Basel 1560](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/4_antwort_auf_joachim_westphal_1560.jpg?itok=Pd3diTmf)

![Fig. 5: Three letters, 1556 Fig. 5: Three letters, 1556 - John à Lasco/Jan Łaski: Epistolae tres lectu dignissimae, de recta et legitima ecclesiarum benè instituendarum ratione ac modo: ad Potentiss. Regem Poloniae, Senatum, reliquos[que] Ordines, Basel 1556](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/5_drei_briefe_1556.jpg?itok=hQ0svO_N)