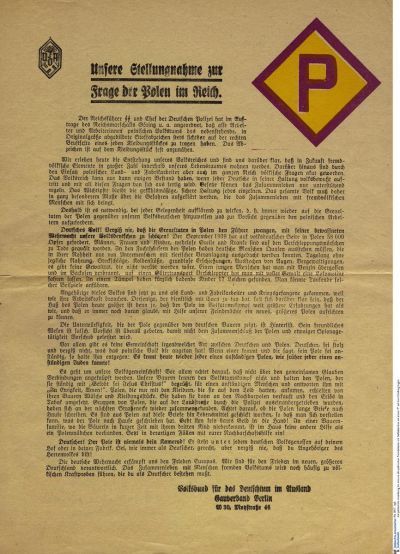

The letter „P“

Julian Banaś, who was forced to work in a Volkswagen factory, left behind comprehensive details about the way he wore his badge: “The camp had two gates and two guards. (…) [There] you were checked to see if your ‘P’ was sewn on. The ‘P’ was a sign of discrimination. I wasn’t ashamed of wearing the ‘P’ because I was a Pole. But I only wore the ‘P’ because I didn’t want to be kicked indiscriminately and be forced to listen to unpleasant and insulting remarks. Since the factory guards always checked whether the ‘P’ was sewn on, I used a coloured thread to sew around the piece of cloth with the letter P. It didn’t match properly and indeed really stuck out. But people could see that it was sewn on. I then fastened the badge with a pin. As soon as I had passed the guards I folded it together and stuck it in my pocket!”

In some factories there were even more refined categorisations. One of these was the Schichau docks in Elbing. Jan Uskwarek, who was forced to work there in 1943, remembers an unintentionally comic scene which might have ended very badly. He was ordered to wear an A (‘Ausländer’: the German word for foreigner) alongside his P – and in every section of the factory the ‘A’s had a different colour. One day a bug crawled under one of these badges just as it was being checked. “The foreman pointed at me with his pencil and asked if that was proof of Polish cleanliness. I felt insulted and replied that it wasn’t my fault. ‘And whose fault is it supposed to be’, he roared back at me, red with rage”. Luckily the situation did not escalate further and later Uskwarek explained to the foreman the reason why the bug had appeared – the forced labourers were only given a small piece of cheap soap once a month and they also had to wash with it; and the hygienic conditions in the camp barracks were anything but good.

The experiences of Polish forced labourers in the Reich were ambivalent. Since they were stigmatised in public and discriminated by a huge number of regulations everything was a matter of chance. Life was often worse in factories because here they were shut up in camps and at the mercy of arbitrary despotism. Furthermore their work became more and more dangerous as the factories were increasingly subject to air-raids. True, work in the countryside was also hard but life could be bearable there depending on which farm you were assigned to. Quite often Polish workers even took their meals with the farmer’s family, something which was strictly forbidden. Romantic relationships between Germans and Poles were equally forbidden. Any Pole who got involved with farm girls whose husbands were serving in the war, or with unmarried girls, was threatened with the gallows; whereas the German women were often pilloried as Polish sluts and sent to a concentration camp. Towards the end of the war when the lack of workers in German industry became ever more drastic, people tried to improve conditions for the forced labourers although the terrible state of food supplies often worked against this. In January 1945 the Central Office for Reich Security put forward proposals for a new Polish badge, a yellow ear of corn on a red and white label – but these were never put into practice.

Peter Oliver Loew, November 2014