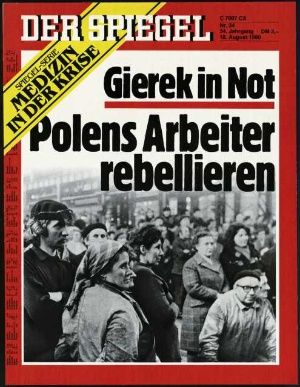

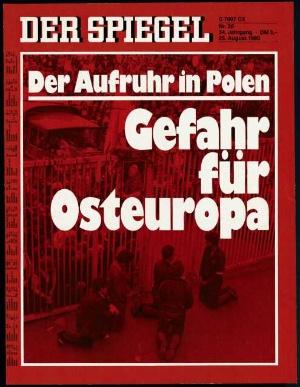

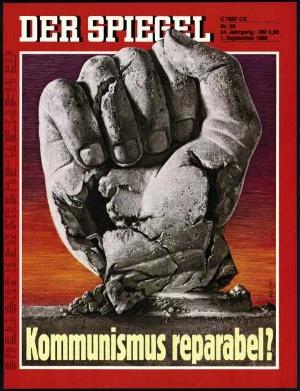

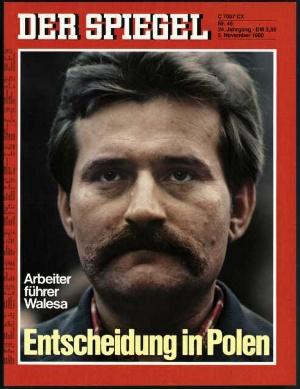

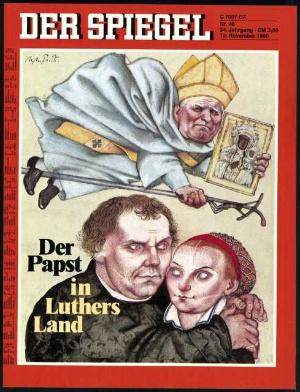

Poland’s path to freedom on SPIEGEL covers 1980 to 1990

Mediathek Sorted

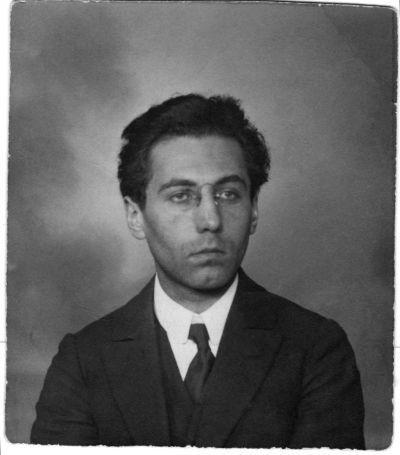

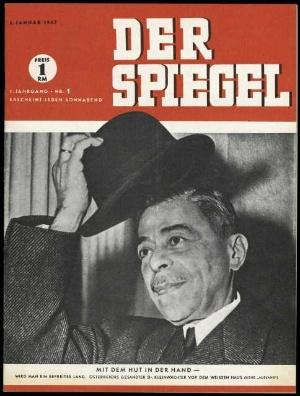

At a very early stage, the SPIEGEL showed its interest in topics relating to Poland by including them in its first issues even though they were still having to make do with relatively few pages. Two articles in the first issue of 4 January 1947 were already devoted to Polish themes and are mentioned here because of their slogan-like headings which were still embroiled in war rhetoric. One text appeared under the title “Lebensraum – rot lackiert” (“Habitat – painted red”), the other was entitled “Noch nicht verloren – polnische Wirtschaft hinter der Oder” (“Not yet a lost cause – Polish economy behind the Oder”). The first article refers to a word from General Władysław Anders to the Zurich newspaper “Die Tat” and states that: “Poland [today] is not in a position to digest the German territories up to the Oder [economically].”[9] The second article, which takes the same line in both its phrasing and content, highlights the fact that, because of the migration of Germans from the former Reich territories and because of its labour shortage, Poland will not be in a position to deal with these upheavals. Barely twelve months later, the SPIEGEL, as the first media organ in the British occupied zone, began to print the diaries of Stanisław Mikołajczyk, the Prime Minister of the Polish exile government who had already stepped down at that time.[10]

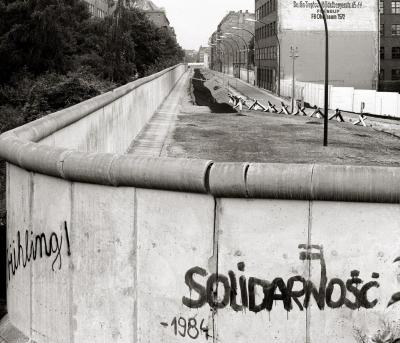

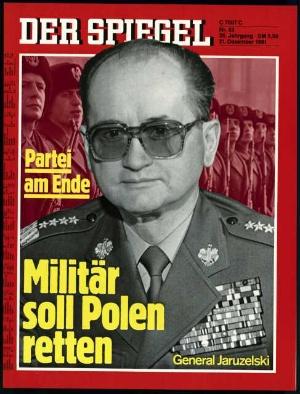

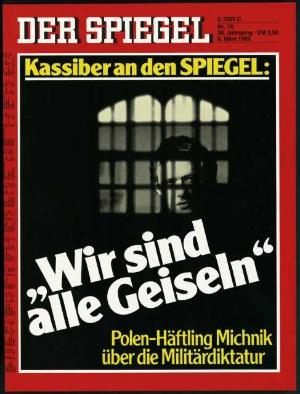

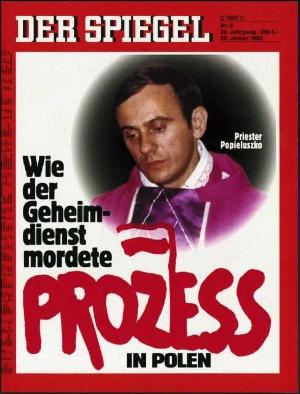

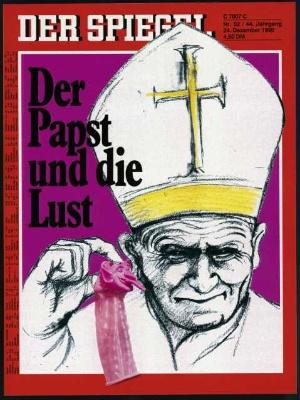

In the 1980s, which were plagued by enormous political crises, Polish topics also appeared more frequently and, similar to the turbulent 1940s, were represented by personalities who were critical of the political system in the country beyond the Oder in the post-war years. Straight after the war it was Stanisław Mikołajczyk and now, almost half a century later, it was members of the opposition, such as Lech Wałęsa, Jacek Kuroń and Adam Michnik, who were turning against the communist government. It should be noted at this juncture that a constitutive feature of the magazine, but also of other opinion-forming media, is that topics are examined in a multivoice discourse from at least two perspectives. Accordingly, the SPIEGEL reported about events in Poland from the perspective of the widely understood opposition and from the perspective of the ruling powers, as is shown by the presence in the magazine of the people mentioned above, but also of Mieczysław F. Rakowski and other important representatives of the Polish United Workers’ party (Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza).

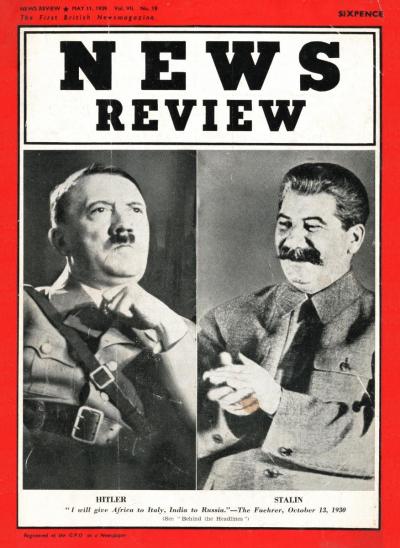

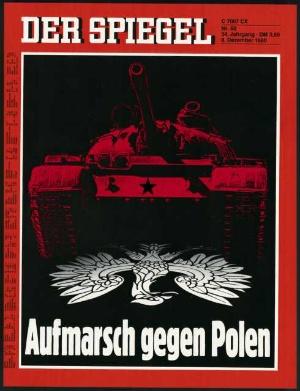

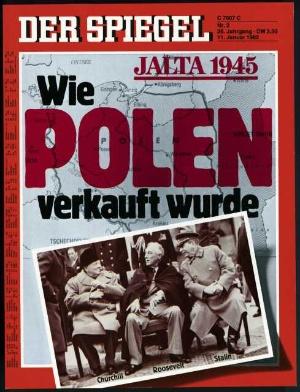

The texts about Poland from the 1980s contain a typical historical philosophical narrative which chooses to use the words “Polish drama” to represent the complicated history of the country. According to Stanisław Mikołajczyk writing in his diaries, “Poland, which is first conquered by Adolf Hitler and later left in the lurch by its allies, might seem to the readers like a faraway land. (…) and its tragedy may perhaps be touted by some as the normal state of Europeans and particularly of Poles. But what happens in Poland today also affects them [the German readers – author’s comment].” – This passage is quoted again by the magazine’s editors in the second issue in January 1982, this time in connection with the quotation from the American author William Faulkner: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”[11] – This passage is quoted again by the magazine’s editors in the second issue in January 1982, this time in connection with the quotation from the American author William Faulkner: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”[12] At the beginning of the 1980s, as the SPIEGEL writes, the “Polish drama” returns and overshadows the past which resulted from the Yalta Conference.[13]