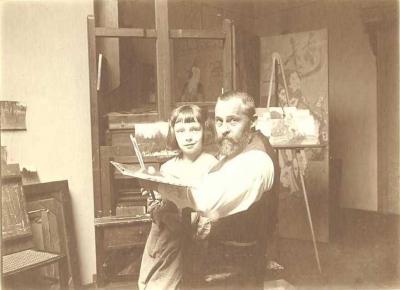

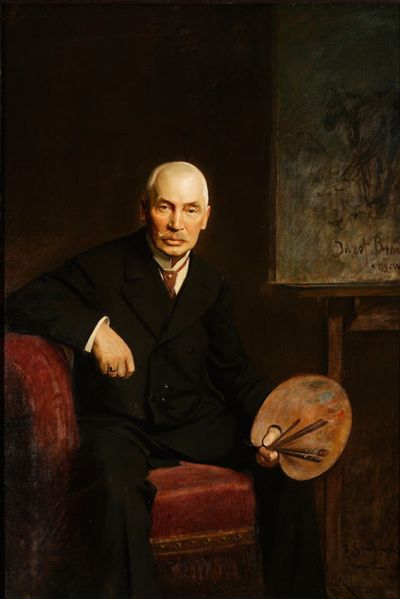

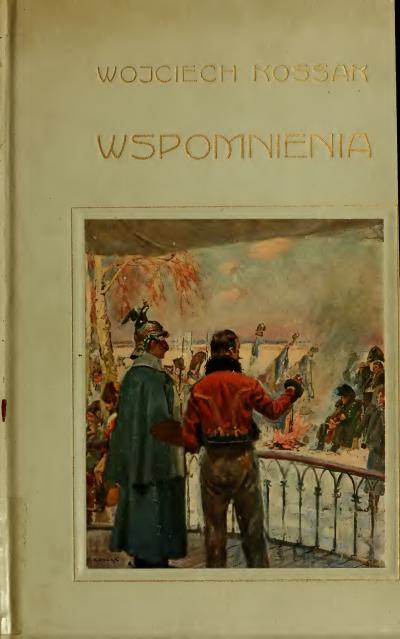

Wojciech Kossak: Memoirs, 1913

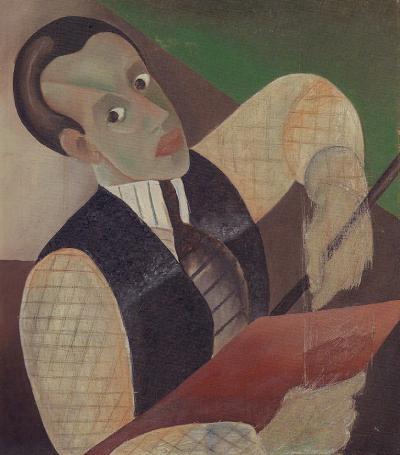

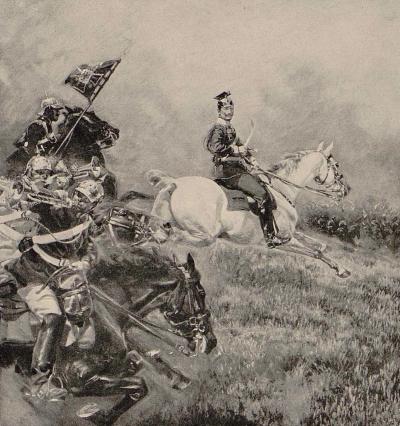

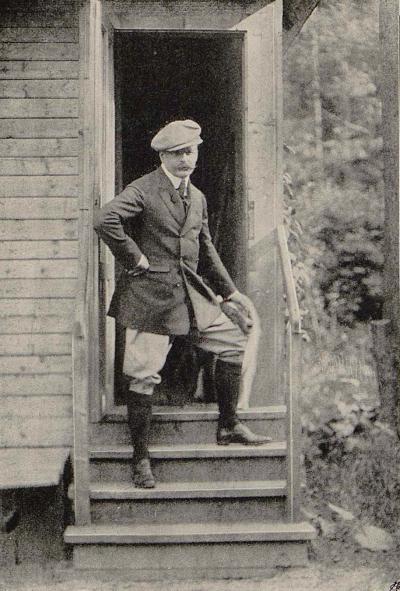

His participation in a manoeuvre at the beginning of September 1899 in the Stuttgart, Metz and Karlsruhe area, his presence at a court ball held by the King of Württemberg in his Stuttgart residence, at an inspection of the King's Ulan forces in Hanover in the entourage of the Emperor (p. 231f.), at the visit of Emperor Franz Joseph I to Berlin on 4th May 1900 as President of the Association of Reserve Officers of the Austro-Hungarian Army (p. 233-238), at the imperial manoeuvres near Stettin in the retinue of the Austrian heir to the throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand (p. 246), at a manoeuvre in Altengrabow in the Jerichower Land east of Magdeburg (p. 251), at parades on the Tempelhofer Feld in Berlin (p. 256) and finally at the inauguration of an officers' casino in Langfuhr near Gdansk, for which Kossak had produced three paintings (p. 260), demonstrate in vivid detail his military and equestrian knowledge, his adept dealings with officers and diplomats, but above all his close connection to Emperor Wilhelm II and the Austrian imperial family. While his participation in manoeuvres was initially due to the task of producing portraits of the Emperor on horseback (Fig. 6) (p. 251), Kossak soon became part of the usual military entourage of the monarch, as the author also revealed in his anecdotes ("The Emperor's Revenge", p. 251-262).

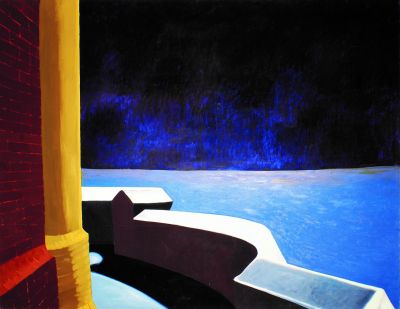

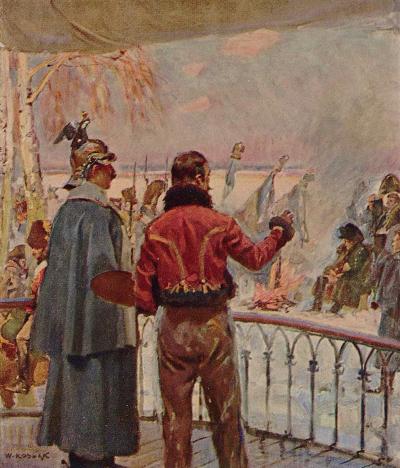

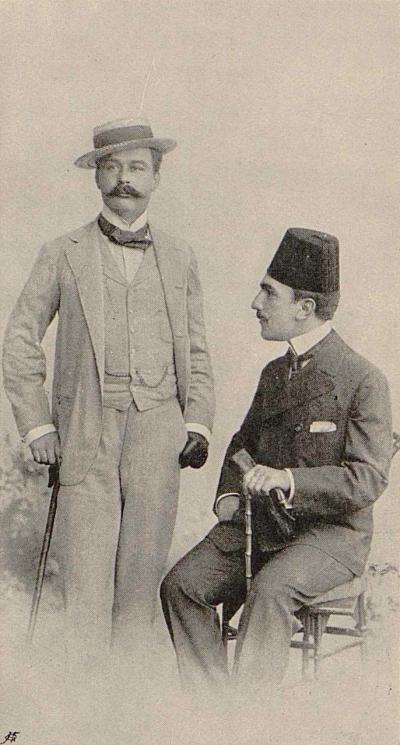

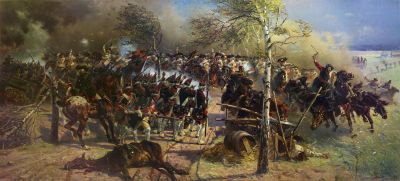

Since the Somosierra panorama could not be created because of the intervention of Prince Imeretynski, Kossak and the Warsaw Panorama Consortium opted for a new theme, the "Battle of the Pyramids" from Napoleon's Egypt campaign in July 1798. In the corresponding month, July 1900, Kossak travelled with Wywiórski to the original site in Egypt, because the weather and lighting conditions should also correspond to the historical facts. They travelled across the Mediterranean from Trieste to Alexandria on a passenger ship belonging to Austrian Lloyd, and from there by train to Cairo (p. 265-271). Kossak was received by Prince Muhammad Ali (1875-1955, Fig. 7), the son of the former Ottoman Khedive of Egypt, who introduced him to the director of the war archives and accompanied him to the battlefields of Embabeh and Giza (p. 271-273). That said, two motifs shown in the book of Kossak's later Panorama, a gun emplacement of the Napoleonic infantry (p. 277) and an attack of the Mamluk army (p. 278) under the leadership of Murad Bey Muhammad show hardly any of the typical elements of the country.

"The end of my life in Berlin was approaching," wrote Kossak in one of the last chapters of his "Memoirs". "At the height of my success, in full possession of imperial patronage and the recognition of Berlin's circles of art lovers, I was to leave this city" (p. 283). As a member of the aristocratic Union Club, which specialised in horse racing, he had close ties to the German nobility in Poland. According to Kossak, this clientele was also affected by the anti-Polish agitation of the Hakatists and the restrictive measures of the Prussian government. On the occasion of a feast of the Order of St John at Marienburg in June 1902, to which Kossak had been invited, but had not appeared "in anticipation of what was to come", the Emperor made a speech, according to Kossak, "personally against the Slavic Front" (p. 286). This incident fuelled his decision to turn his back on Berlin immediately and forever. He accepted an invitation from the Emperor to visit the Guard Cavalry at Tempelhofer Feld, during which Wilhelm advised him of extensive commissions for paintings, including a portrait of the Empress on horseback. As Kossak sums up, "this list of large works ordered en masse was an attempt to "hold back the painter in Berlin while there was still time". (p. 293)

Back home, Kossak received telegrams from Poland criticising his alleged participation in the St John's festival at the Marienburg, as well as a message from his brother Stefan, requesting him to correct corresponding reports in the Polish press. Kossak telegraphed the newspapers in Poland that he had not been to Marienburg and explained to his brother that he had decided to leave Berlin because of the intolerable situation (p. 293 f.). A visit by the imperial couple to his studio in Monbijou Castle, where Wilhelm sat for a portrait of himself on horseback, took place in a tense atmosphere: "While I thanked and accompanied their majesties to the park gate, I was totally aware that I would never again find such a powerful and benevolent patron of my art in my life". Wilhelm, who had no knowledge of Kossak's final farewell, wished the painter a swift return from his holidays. The following day the entire telegram to Kossak's brother, who had given it to the press in Lemberg, was published in the Berlin newspapers (p. 294-296). Kossak had the commander of Plessen convey his gratitude to the Emperor and explained that he had "lost his moral peace as a result of the latest political events ..." that "my conscience is in doubt as to whether I, as a Pole, may now continue to work here" (p. 297). Kossak used his last week in Berlin to complete painting commissions and settle some personal matters.

[21] The text of Wilhelm II's speech on the occasion of the Johanniter Festival on 5 June 1902 at the Marienburg: "I have already taken the opportunity to emphasise in this castle and at this point how the old Marienburg, this former bulwark in the east, the starting point of the culture of the countries east of the Vistula, should always remain a landmark for German missions. Now it is time once again! Polish arrogance is trying to get too close to the Germans. I am compelled to call on my people to preserve their national estates, and here in the Marienburg I express my expectation that all the friars of the Order of St. John will always be at my service when I call on them to uphold the German way of life and customs". (Die Ostmark. Monatsblatt des Deutschen Ostmarken-Vereins, Juli/August 1902, page 41; quoted from: Tzu-hsin Tu: Die Deutsche Ostsiedlung als Ideologie bis zum Ende des Ersten Weltkriegs, Kassel 2009, page 151)