Marian Stefanowski – photography

The nomad or in search of a piece of freedom. Looking at the photographic work of Marian Stefanowski

“One absolutely must return to the places of longing otherwise one burdens the world unnecessarily with one’s longing”

Aleksander Janta

“You know that there is no forgiveness, your repentance is in vain. So be what you are supposed to be: a man. At some time grass will grow over your life as well.” [*]

Attila Josef

In his attempt to define the late style, Theodor W. Adorno wrote that it is what happens when art demands its rights. In other words – the late style is the stage in the creative art in which the artist is clear about what he has already created and what he has not, by the fact that he stops referring to something that goes beyond the entirety of his own experiences.

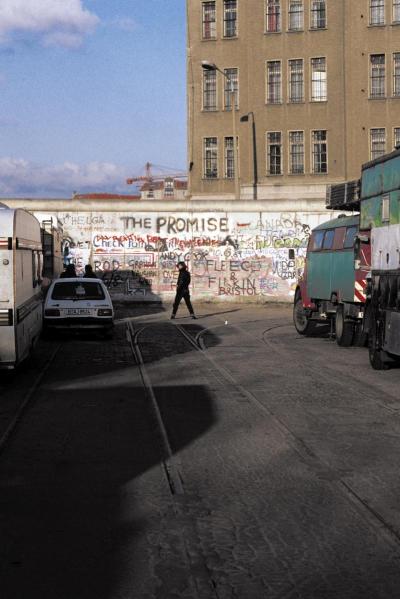

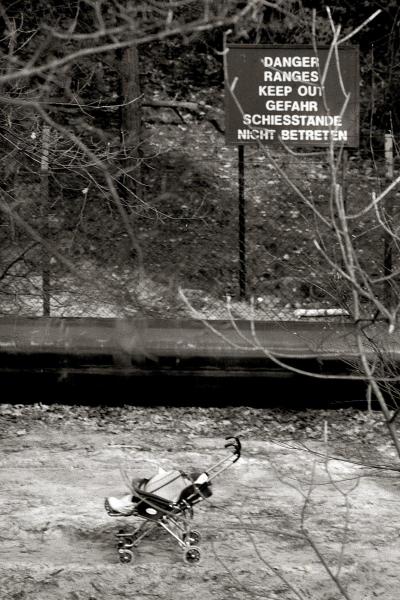

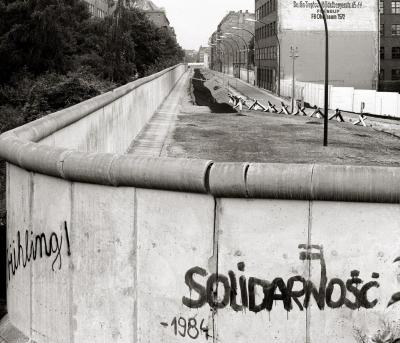

The works of Marian Stefanowski are not reports. On the face of it, they depict reality and can be associated with specific places. Of course, the art of photography requires new areas of expression, requires closer contact with the observer and always increases the dramaturgy, the attractiveness. In this case, however, the photographically disenchanted places – both the real ones and the imaginary – serve to create a story, and this creative process lends order to the photographer’s experiences and gives them meaning. We only experience the fact that time is slipping away when we fill it up somehow, wrote Alan Budrick in his essay “Why Time Flies” from last year. Meaningless waiting does not excite or satisfy our curiosity. So do the photos by Stefanowski create an artistic utopia? Or do they in fact portray a meticulous analysis of the world around us? What is it that makes up the essence of his pictures?

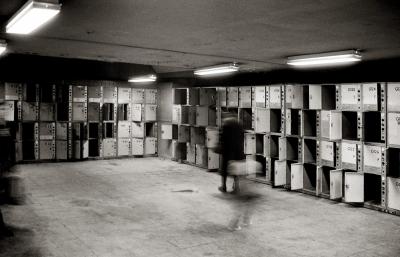

It was the pioneer of modern experimental psychology, Wilhelm Wundt, who in 1868 for the brief moment in which impressions make up our feeling for the present, suggested that the space be treated as an image of the consciousness and thus also as an image of human identity. Stefanowski’s photographic depictions of landscapes do not have any specific reference to time and space, they exist so to speak outside the political, social and religious context. Outside reality. It appears as if their metaphorical message is more important than what is actually portrayed in the picture. Some of the images are even dispassionate, without feeling, and despite this ... they do not leave you in peace. And even if the person does not appear in them, they tell his story.

The photographic travel diary (Diary of a Traveller) is the composition of the narration about himself and the construction of the identity label. That is why the civilisation keys are less comprehensible, instead it is the personal aspects that illuminate the angles of the mind - the knowledge about oneself, self-awareness, the possibility (as well as the will) to tell others about it.

The history of travel diaries dates back to the 17th century and is connected to the whole mythology of people going on a pilgrimage. Completing the grand tour was an absolute necessity, a common practice and part of an enlightened education. Nothing connects intercultural groups more than travel.

With the photographic maps of his travels, Marian outlines the limits of his creative territory for himself. However, he suggests an unwritten agreement for the connection between artist and observer: should the observer decide beyond the limits of the territory that let him enter or into which he was invited. Should he breach these limits or not. At the same time as making this decision, we touch on issues of perception or of their changeability – as a rule we see what we expect to see and what we want to see.

There then remains only the obligation to explain the situation to the writer (person), to that person who enters into a special relationship with the photographer for the duration of the writing process. The photographer has a lot to do with the psychological phenomenon of calling to mind, that is registering the factual whilst remaining as true as possible to the facts at the time of its creation. Facts are sacrosanct and the photographer is the direct, and also the only ‘realiser’ of the idea when he brings these facts back to mind.

The writer gets a first-class product offered to him but when they are given to him, he has to overcome a number of boundaries.

This means that mutual awareness and trust is required between the two people mentioned.

Magda Potorska, March 2018

Translation from Polish: Dagmar Domke

[*] Translation from Hungarian: Laszlo A. Marosi