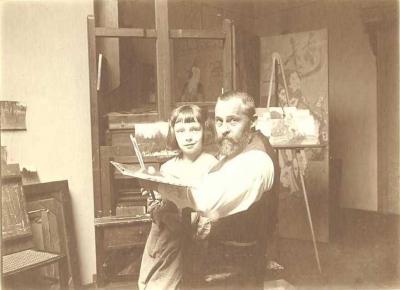

Ateliers of Polish painters in Munich ca. 1890

Mediathek Sorted

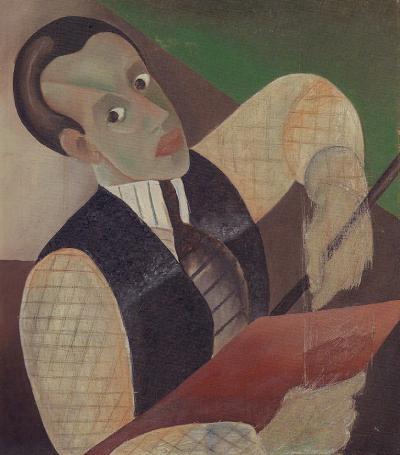

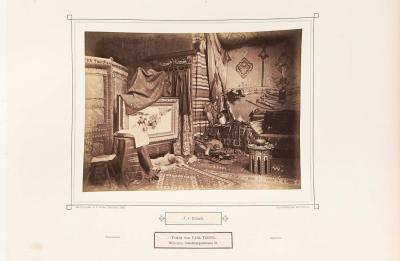

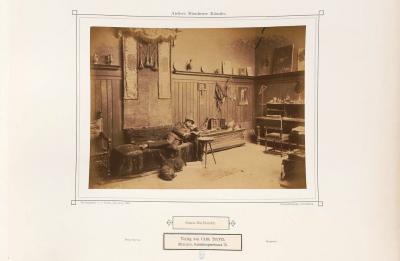

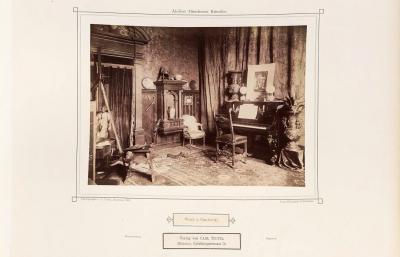

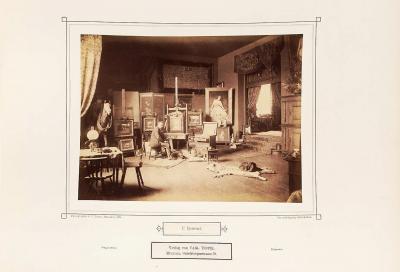

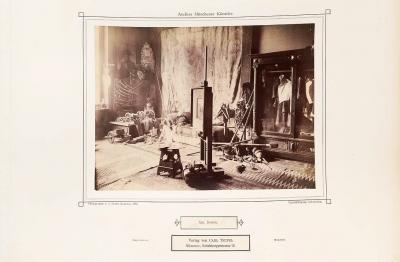

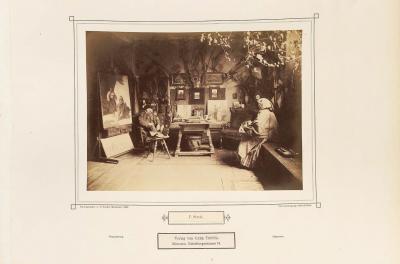

The furnishing of the Polish artists’ ateliers with their collections and paintings on display, just as Teufel had photographed them around 1890, certainly lived up the expectations of the public, i.e. the high-ranking visitors, collectors, and gallery owners, who expected from the Poles nothing less than an unknown, “exotic” or ideally a picturesque Europe,[145] which even resembled the “orient” when the Turkish wars or the people, landscape and acts of war from the eastern borders of Poland were involved. The impression that the Polish art of painting was different persisted over decades, even if it mainly related to the core group of artists around Brandt and Wierusz-Kowalski. In January 1875, the Munich art critic and curator at the Alte Pinakothek, Adolf Beyersdorfer (1842-1901), wrote in the Viennese daily newspaper “Neue Freie Presse”: “Gierymski and his associates thus show the world in its poorest garb: a Polish dump, a patch of Puszta with scant grass and undergrowth and six miles of free views into the blue – sometimes some extravagance in the foreground, e.g. a bunch of thistles or a water pool – a moor tavern, with chalk white walls turned to the sunlight or an entire village, a dark group of houses packed together at night or at dawn […], a real suicide atmosphere – in short, everywhere the deliberate soberness and desolation of a wretched nature.”[146] Nearly three decades later in 1903, the painter, architect and writer Stanisław Witkiewicz (1851-1915), judged that the paintings of Brandt and his circle portray a fairytale world to foreigners, “whose form, movements, actions and behaviours, clothes and weapons astonish observers with their exceptional nature.” One would have searched elsewhere in vain for such helmets, sabres, robes, such a mass of unusual things, picturesque inns, slanted straw roofs, muddy ditches, and derelict mills. [147]

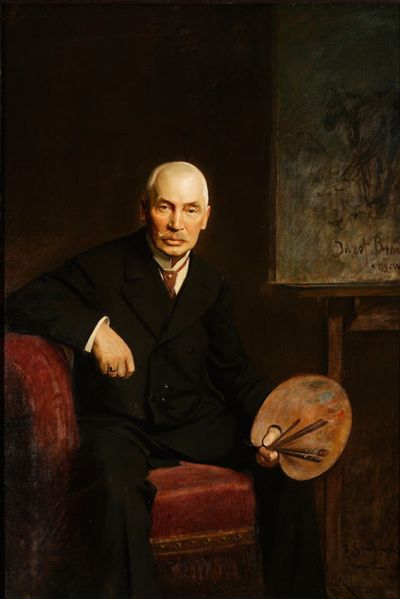

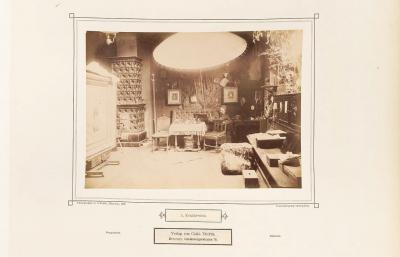

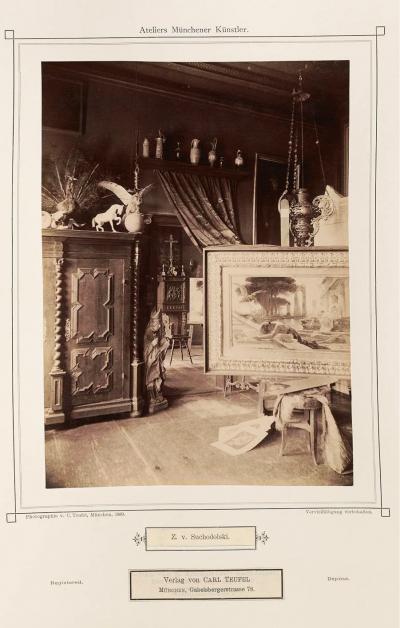

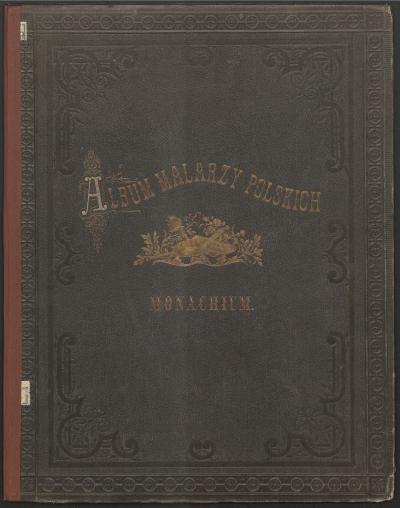

The collections in the ateliers of the Polish artists, especially those of Brandt (Fig. 1, 2), Kozakiewicz (Fig. 11), Rosen (Fig. 14, 15) and Pułaski (Fig. 13), did not just serve as models for their paintings, they also attempted to preserve the museum-like impression of being something different and picturesque for decades. They certainly represented a piece of home for each individual artist, but were, at the same time, an important part of their sales strategy.

Axel Feuß. January 2018

[145] Anna Baumgartner (2015, page 33-35, see literature) critically discussed the concept of the “Exotic” in relation to Polish painting at this time, as it is used today by Polish art historians but which was not used in contemporary art critiques of the second half of the 19th century.

[146] Adolph Beyersdorfer: Neue Kunstbestrebungen in Munich IV., in: Neue Freie Presse, No. 3745, Vienna, 29 January 1875, page 1 (digital reproduction: http://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=nfp&datum=18750129&page=1&zoom=33)

[147] Stanisław Witkiewicz: Aleksander Gierymski, Lwów 1903, page 20 (digital reproduction: http://cyfrowa.chbp.chelm.pl/dlibra/doccontent?id=11097)