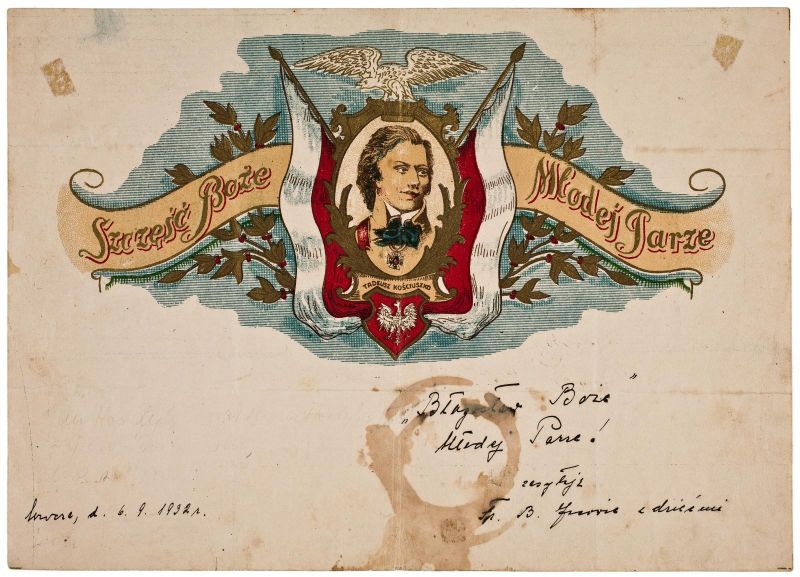

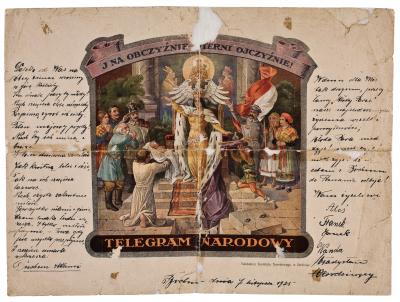

“Faithful to the Fatherland, even in foreign lands”. Patriotic telegrams from the Polish diaspora in Wrocław

Mediathek Sorted

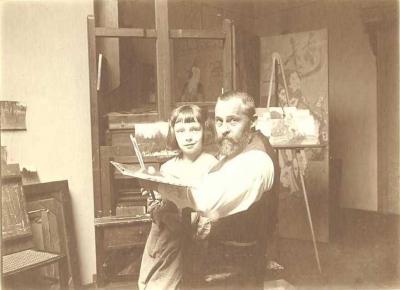

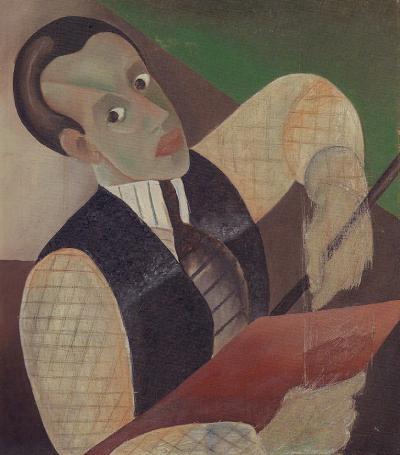

In 1894, the celebrations of the 100th anniversary of the Kościuszko uprising were approached with particular fervour. They were held in all three occupied regions, Prussia, Russia, Austria, but achieved their greatest response in the autonomous Galicia. In Lemberg, the highlight of the festivities was revealed to be the circular painting entitled “Panorama Racławicka“ (Panorama of the Slaughter of Racławice) by Jan Styka and Wojciech Kossak. “For people in the occupied regions, it helped to ‘cheer their hearts’, it awakened feelings of national pride and it demonstrated a vision of the battle for the independence of their homeland in which the associations from the peasant masses would take part, something that ideologists and freedom fighters in the 19th century could only dream of.”[1]

Tadeusz Korzon also published the first scientifically sound biography of Kościuszko in the anniversary year of 1894.[2]

The celebrations on the anniversary of Kościuszko’s death in 1917 took on quite a different format. The events were celebrated with religious services, processions and speeches in at least 100 small towns and even in villages. And that’s how, on 14 October 1917 on the fields of Racławice on which the first battle of the uprising was won, there came to be a holy field mass and a large-scale rally, in which almost 15,000 young people, farmers and inhabitants of the surrounding villages took part, as well as a performance by the Krakow Teatr Ludowy (People’s Theatre) with a production of the play “Kościuszko pod Racławicami” (Kościuszko in Racławice) by Władysław Anczyc.[3]

Some places put on spectacular shows. These included two military aircraft, which flew over the town of Lublin raining down red and white bouquets and the pilots’ calling cards on which was written: “Kościuszko Festival on 15 October 1917”[4] In 1917 celebrations to honour Kościuszko were also held in some foreign cities, including Paris, Berville, Solothurn and Rapperswil.

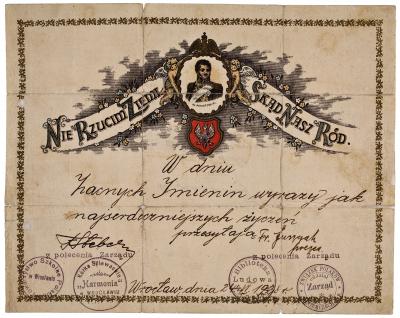

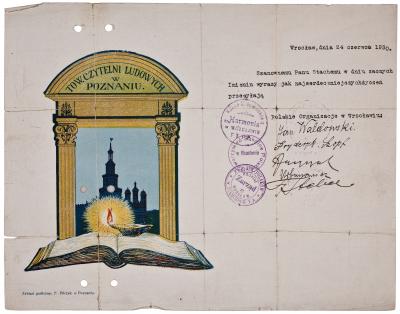

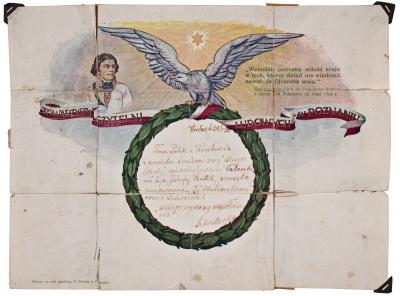

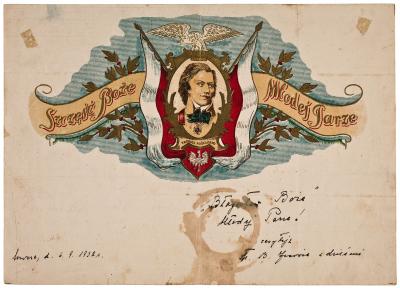

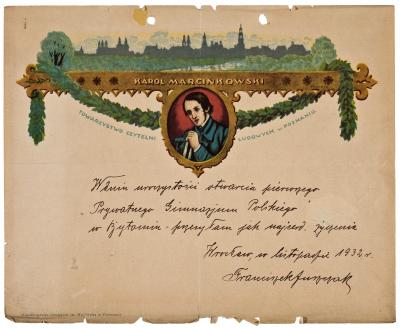

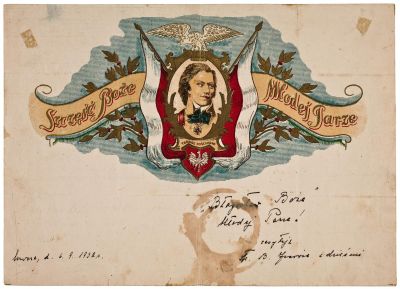

It is also worth noting that celebrations were also held in the German town of Wrocław. The festival committee there worked for more than six months to ensure that they honoured the memory of the Polish national hero with dignity. The Kościuszko festival opened with a holy mass which was held on Sunday, 14 October 1917 in the church of the Mariahilf educational institution in Lehmgrubenstraße (today ul. Gliniana) which was packed to the rafters. Pastor Wilczewski delivered a spirited and extremely patriotic homily. Delegations of Polish organisations attended this holy mass waving their banners. The mass ended with the strains of the patriotic song “Boże coś Polskę” (God save Poland). There then followed an amateur performance of the play “Kościuszko w Petersburgu” (Kościuszko in St. Petersburg) in which the way the leader was interpreted by the protagonist was particularly impressive. The correspondent from the daily newspaper “Dziennik Poznański” highlighted the celebrations in his report: “In spite of the foreign surroundings, the Polish diaspora in Wrocław has demonstrated that it lives, that it feels Polish and that it will always remain genuinely Polish.”[5]

In the region of Greater Poland, which was under Prussian rule, the celebrations were held in Poznań and places such as the small town of Pleszew, where a crowd gathered around a bust of Kościuszko on a children’s playground decked out in the national colours. Red and white cockades were distributed amongst the people attending the celebrations, patriotic poems were read out, scouts sang Polish hymns and a hundred couples in Krakow traditional costume performed a Polonaise, the Polish national dance.[6]

[1] K. Olszański, Panorama Racławicka – rys historyczny (1892 – 1946), [in:] Studia Historyczne, Volume 24 1981, Issue 2 , p. 227.

[2] M. Micińska, Gołąb i Orzeł. Obchody rocznic kościuszkowskich w latach 1894 i 1917, Warszawa 1997, p. 53-55.

[3] Ibid, p. 111-112.

[4] “Kurier Lwowski”, No. 484 of 16 October 1917.

[5] “Dziennik Poznański”, No. 239 of 19 October 1917.

[6] A. Gulczyński, Harcerstwo pleszewskie do roku 1939, Pleszew 1986, p. 9.