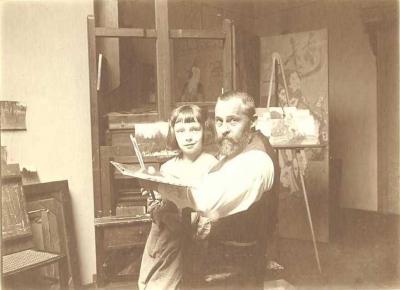

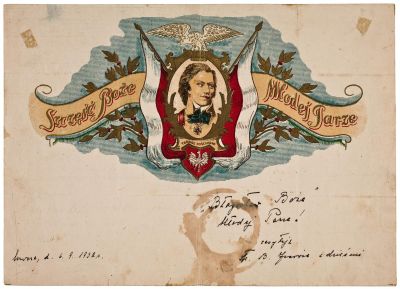

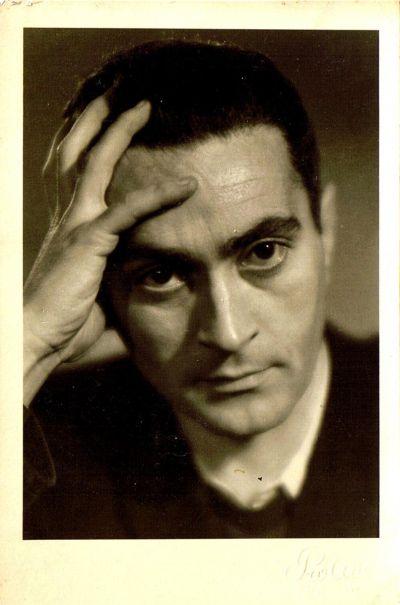

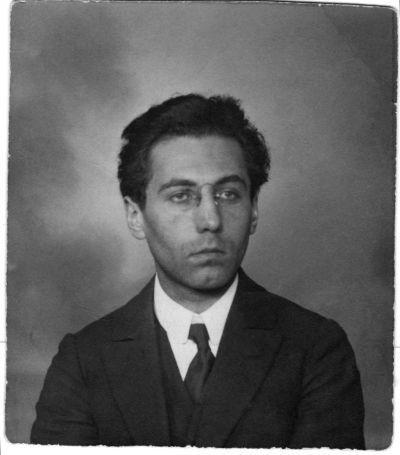

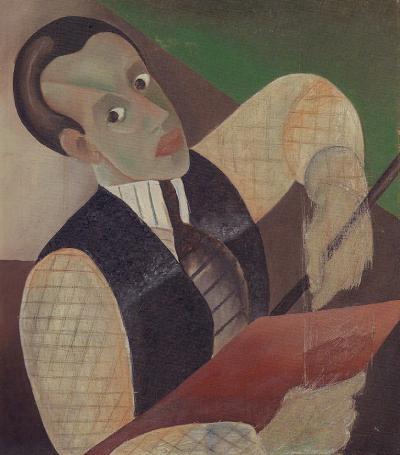

Jesekiel David Kirszenbaum (1900–1954). Student of the Bauhaus

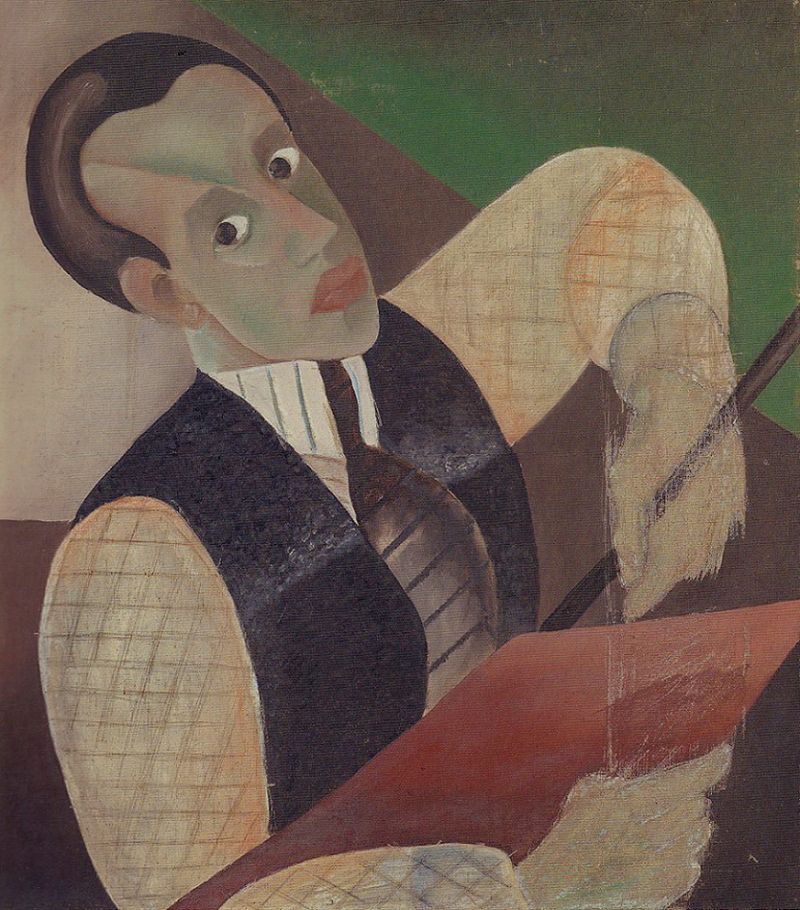

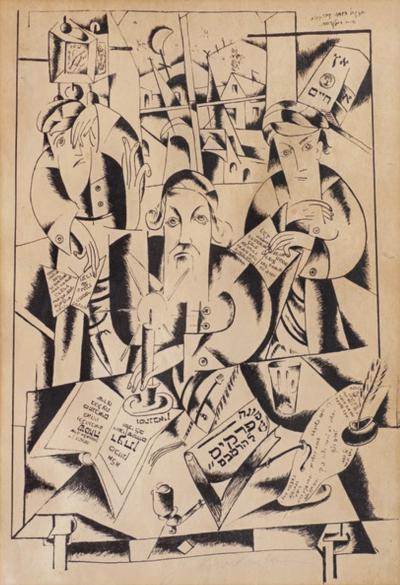

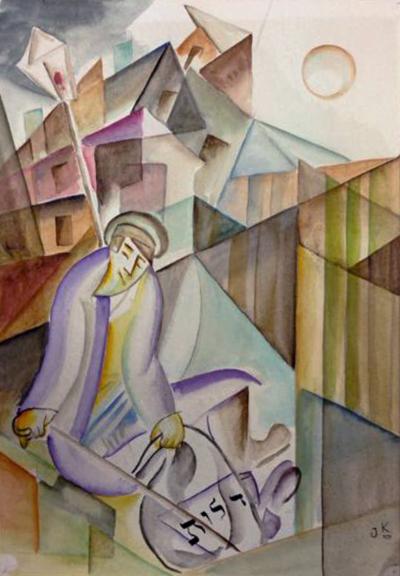

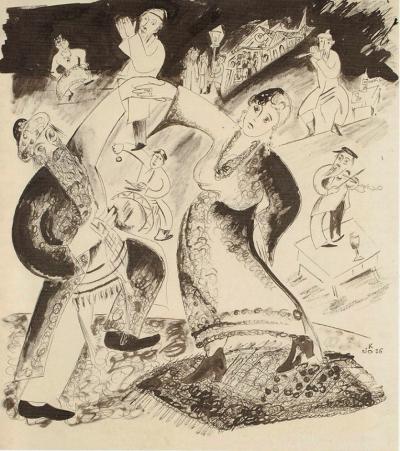

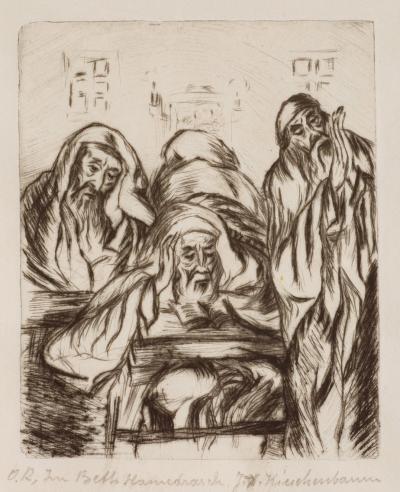

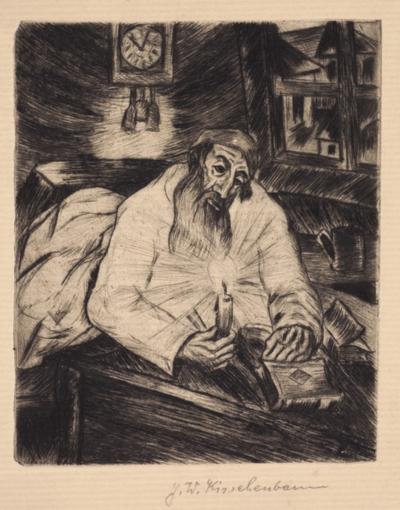

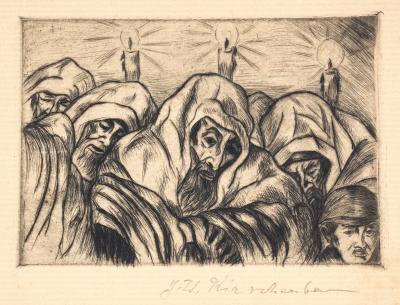

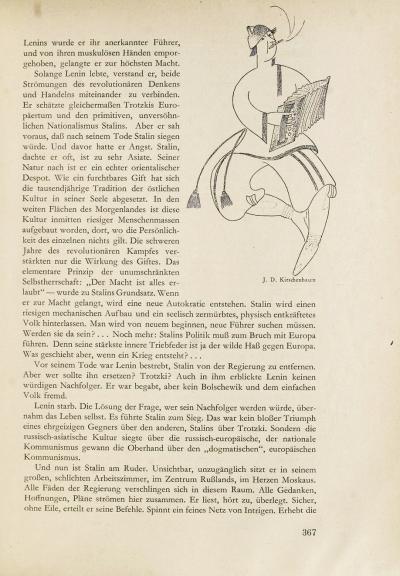

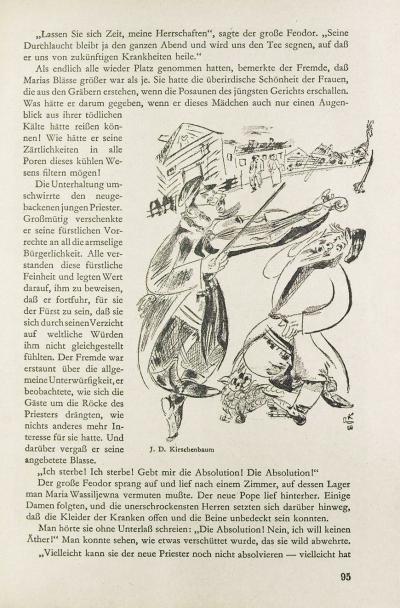

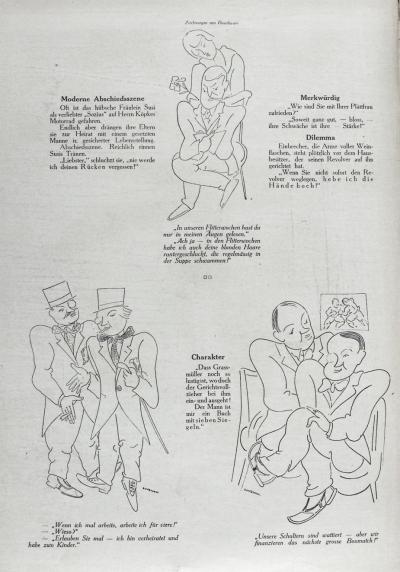

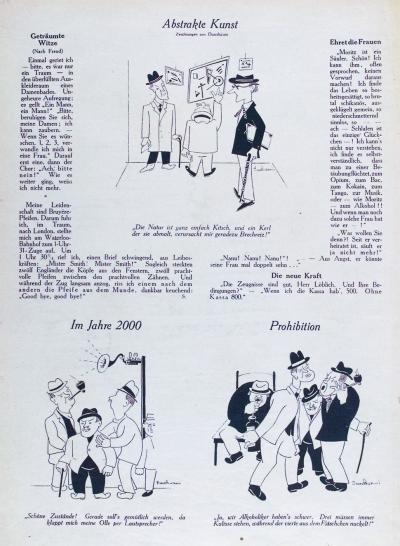

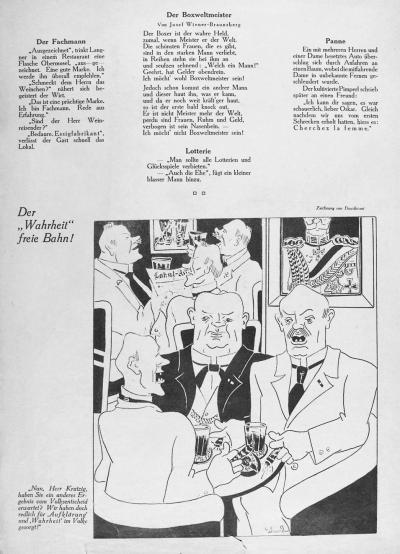

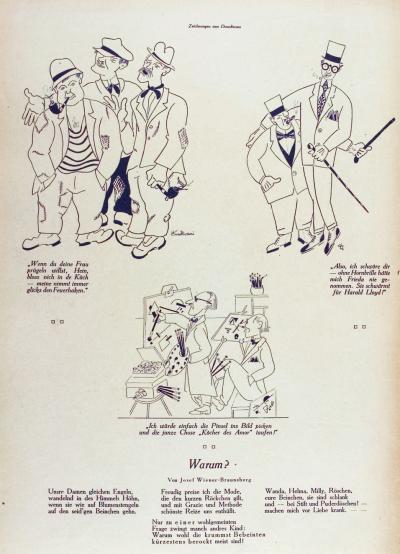

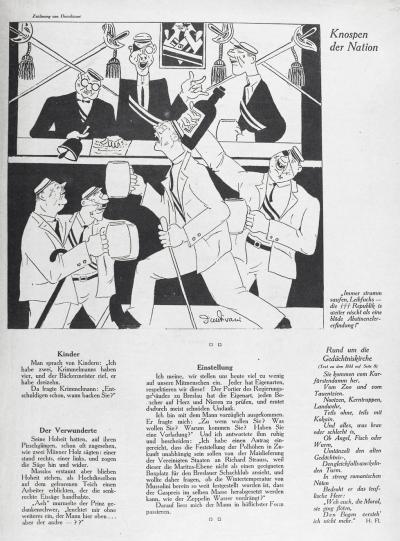

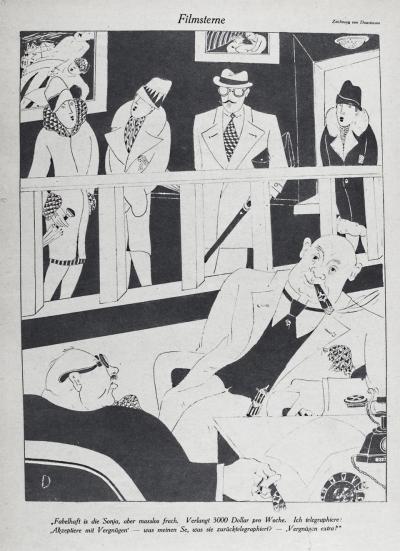

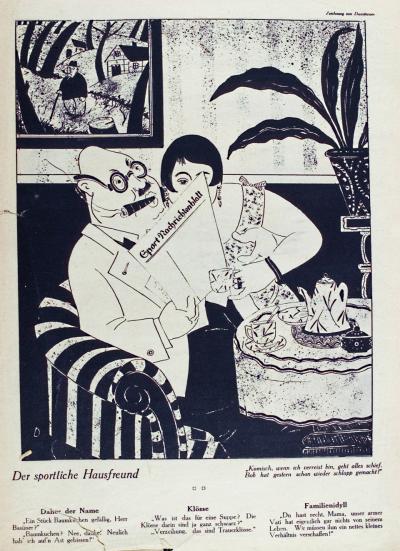

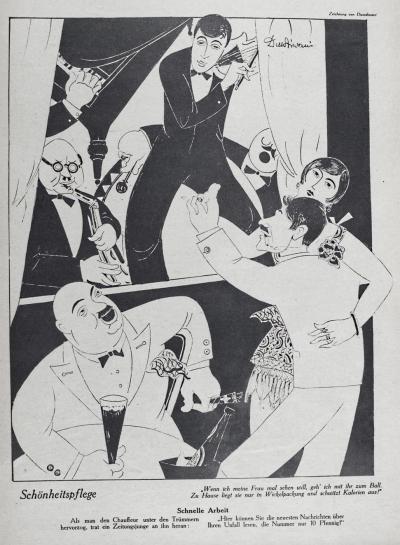

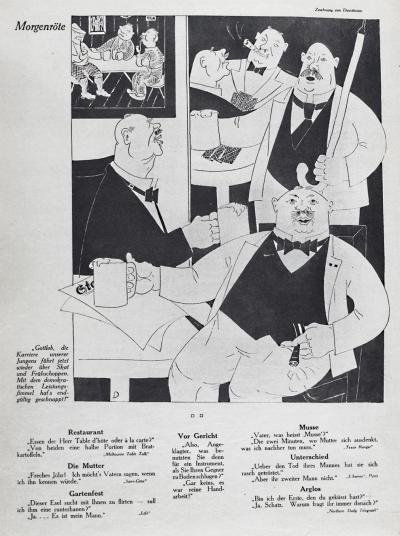

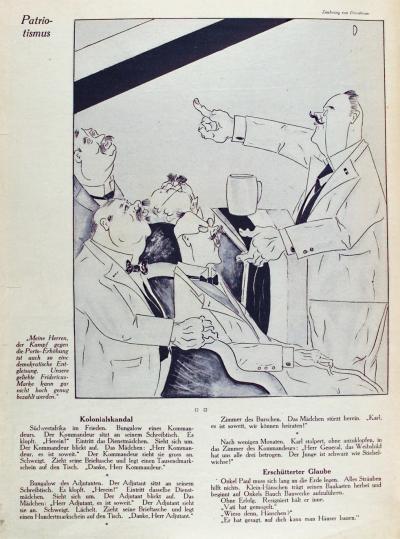

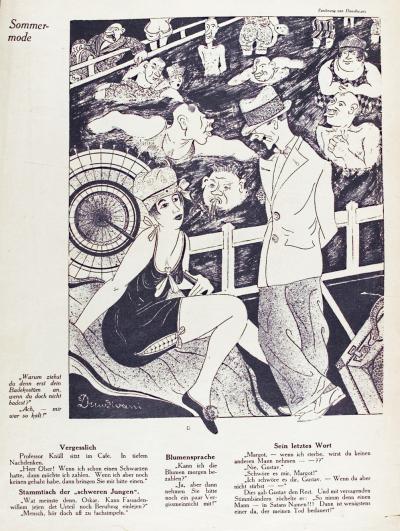

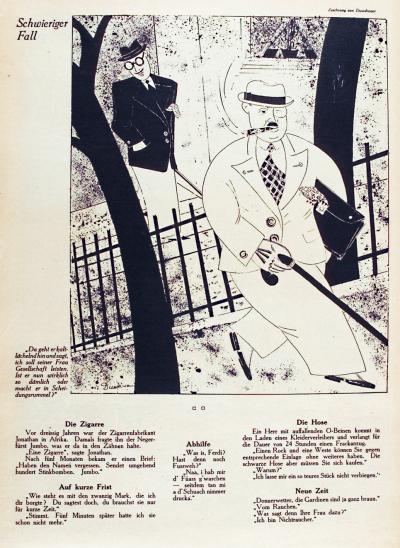

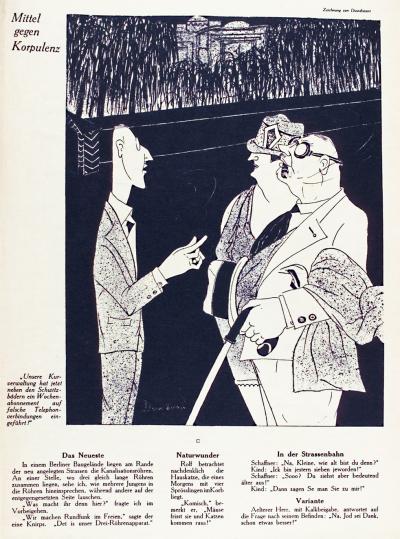

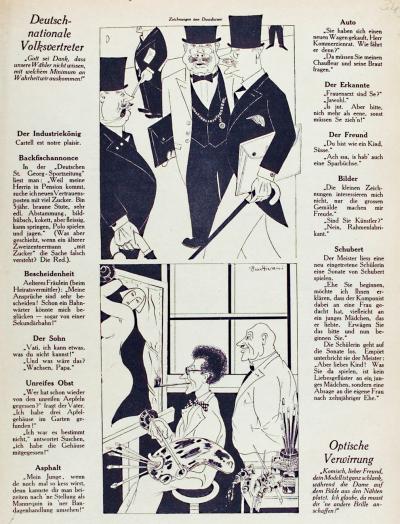

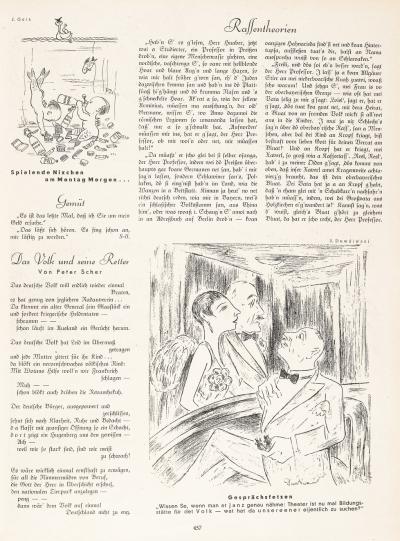

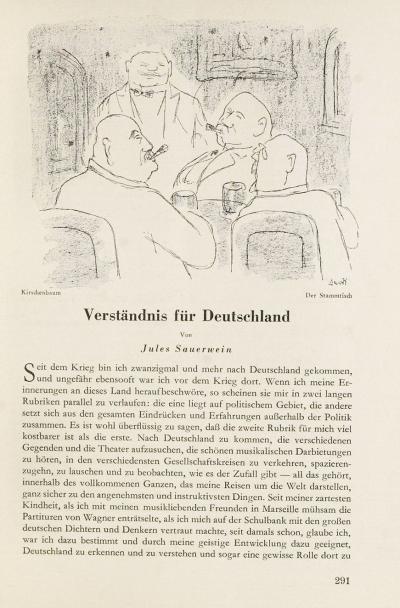

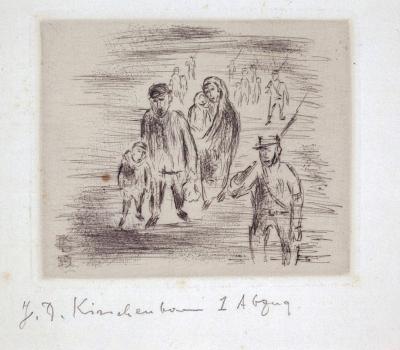

This stylised, light-hearted style is also evident in the satirical drawings, which were presumably produced in 1925/26 but which appeared in Der Querschnitt in later years (Fig. 12-14) and included another obviously blind fiddler in the shtetl clashing with a passer-by. Kirszenbaum began producing cartoons for Ulk in spring 1926, initially with somewhat simple contours (Fig. 15-16, 19) but by July they had already evolved into large-format, elegant but acerbic social scenes defined by strong monochrome contrasts (Fig. 17, 18, 20-31). Well-known cartoonists, like Eduard Thöny, Thomas Theodor Heine, Olaf Gulbransson and Karl Arnold, who worked for the magazines Simplicissimus and Jugend from the end of the 19th century, were still active in the 1920s and 1930s, and were joined by young illustrators, such as Herbert Marxen.

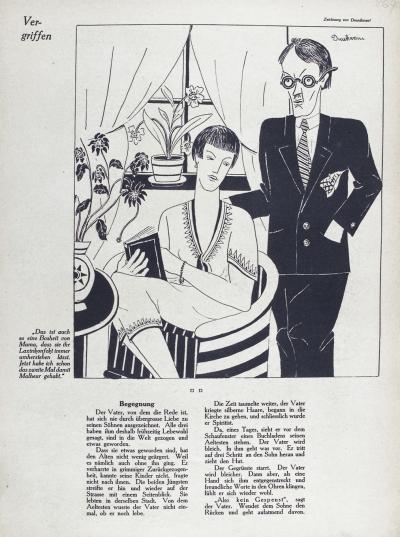

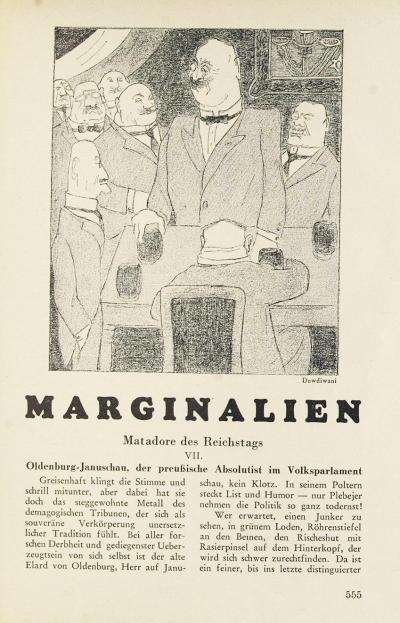

Kirszenbaum gave this long-established style a new note by taking the scenery and physiognomies favoured by George Grosz as his guide. Since the appearance of his portfolio “The face of the ruling class” (1921) as well as in his painting “Pillars of society” produced in 1926 (Berlin National Gallery/Nationalgalerie Berlin), Grosz had systematically worked his way through the institutions of the Weimar Republic, politicians, the Christian churches and the conservative bourgeoisie lampooning the petty bourgeois, double standards, militarism and moral decline. Since 1926, Grosz had also worked for Simplicissimus, the Eulenspiegel and later for the Roten Pfeffer. The victims of Kirszenbaum’s graphic exaggerations and ridicule were the conservative bourgeoisie loyal to the Kaiser (Fig. 17), German Nationalist fraternities and politicians (Fig. 20, 25, 30 top), managers and fat cats (Fig. 21), ponderous family men (Fig. 22) and spare-time politicians (Fig. 26) as well as the high society (Fig. 29) or so-called “modern” artists (Fig. 30 bottom). Thanks to his talent for illustration, these characters would also have been recognisable without the literary satire and witticisms added by the editorial department.

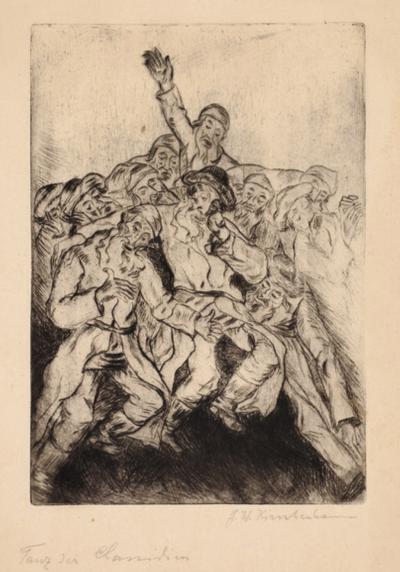

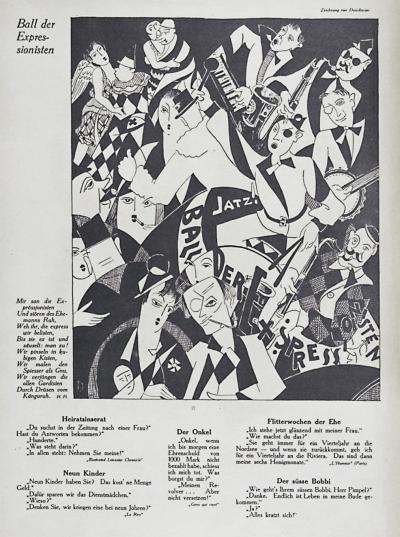

He also drew more benign social scenes that accurately characterised the dress and standard of living in the “Golden Twenties” (Fig. 18, 23, 24, 27, 28). The style of these works leans on that of the New Objectivity/Neuen Sachlichkeit, as represented by Rudolf Schlichter, Otto Dix and others, whose critically caricaturing undertone influenced Kirszenbaum. He enjoyed particular success with his three-quarter page cartoon “The Expressionists’ Ball” (Fig. 31), in which he combined all the aforementioned styles with the written interjections of Dada and the prismatically blended composition lines of expressionism. With this combination, he created a comprehensive picture of the culture and customs of the time. From the beginning of the 1920s, artists balls, hosted by the academies and art schools or by free artists’ associations, were considered the annual highlight of social and cultural life, not just in Berlin. The cartoons for Jugend became more benign again (Fig. 32-34). However, in the two drawings published in the Querschnitt in 1931, the artist found himself focusing on male figures again, which Grosz and Dix had modelled before him (Fig. 35, 36).

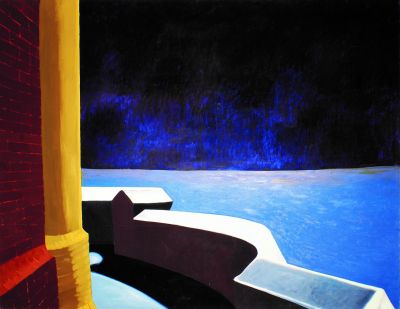

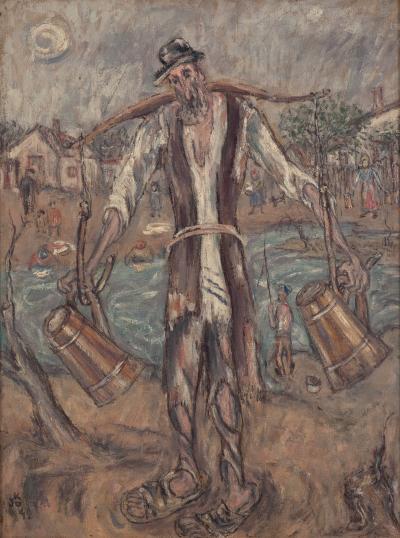

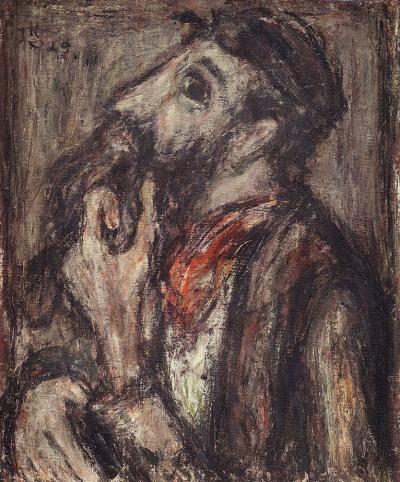

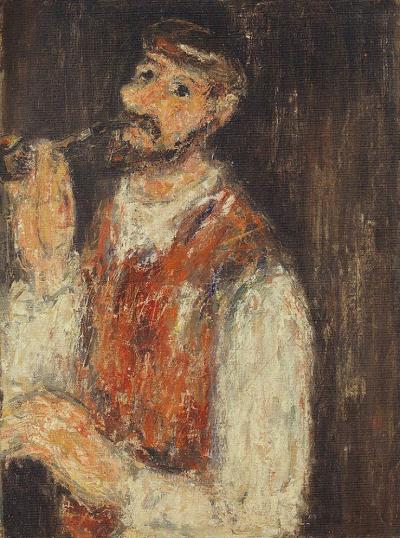

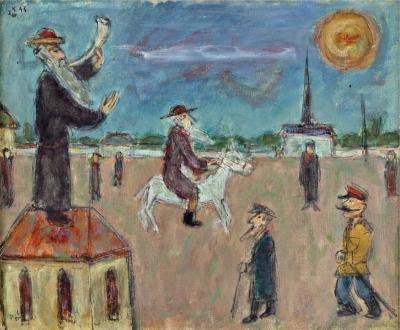

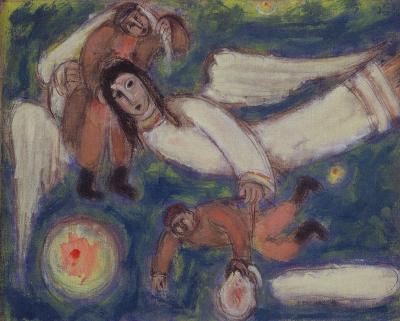

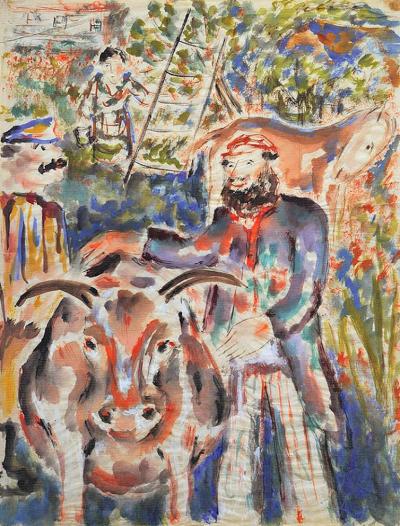

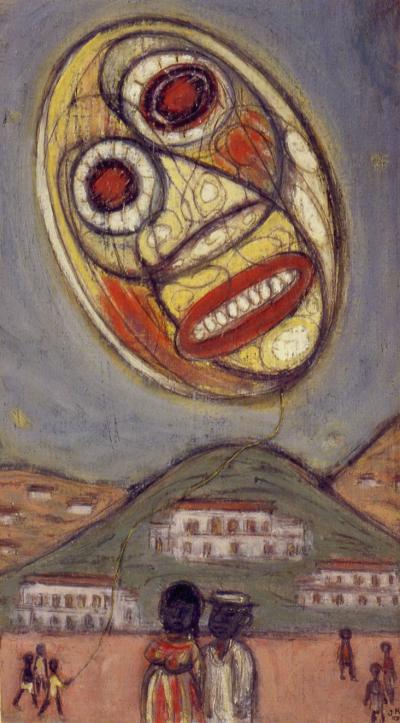

In 1933, Kirszenbaum and his wife fled from the National Socialists to Paris when they found themselves in great danger, not just because of their Jewish heritage but also because of their close contact to the communists. They left all their possessions behind in Berlin, including nearly all of the artist’s works. Kirszenbaum appears to have settled in quickly. In November 1933, he took part in the Paris Autumn Salon, the Salon d’Automne, which started in 1903[56] and which had been dominated since the 1920s by painters from the Montparnasse artists’ quarter, including Chagall, Modigliani and Braque. It was considered the most important exhibition venue of the Avantgarde. Kirszenbaum exhibited there until 1935.[57] In November 1933, he also showed landscape paintings at an exhibition organised for the benefit of displaced artists from Germany by the French committee for the protection of Jewish intellectuals.[58]

[56] L'Écho de Paris of 3 November 1933, page 5, 5th column, first paragraph, online resource: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k8149828/f5.item. In the beginning, the artist obviously used a French spelling of his name “Kirchenbaum”, then later the German spelling before finally returning to the Polish spelling.

[57] Letter from Kirszenbaum to the Director-General of the French National Contemporary Art Collection/Fond National d’Art Contemporain in Paris dated 20 April 1945, pictured in: J.D. Kirszenbaum 1913 (see Literature), page 24 f.

[58] The persecuted intellectual Jews. Notices, in: Le Temps dated 1 November 1933, page 4, 2nd column, online resource: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k2493917/f4.item; also “Kirchenbaum” there