Adalbert and Elisabeth – a Ruhr Polish altarpiece in Herne-Röhlinghausen

Mediathek Sorted

A prominent Polish national saint

Adalbert (born around 956) came from a noble family of the Slavnik clan, whose territory lay in the eastern and southern Bohemia. He received his education at the cathedral school in Magdeburg. In 981, Bishop Thietmar of Prague brought him into the clergy of St. Vitus in the castle district (Hradčany) in Prague and ordained him as a priest. When Thietmar died the following year, he was succeeded by Adalbert. However, the young bishop soon came into conflict with the Bohemian nobility and parts of the clergy, since he took decisive steps to counter problems that had arisen in the church. In 988, he was forced to leave Prague. Although he returned to Bohemia, he did not remain there long (approx. 992–995) due to ongoing disputes with the nobility.

In 996, Pope Gregory V granted the unsuccessful Prague bishop’s request to be given a new mission: converting the heathen peoples in eastern Europe to Christianity. The following year, Adalbert moved to Gniezno, where he met the Polish duke Bolesław Chrobry in the region inhabited by the Old Prussians, which would later become West and East Prussia. After initially preaching in the Gdańsk area, his work in Samland was met with fierce resistance: on 23 April 997, the unwelcome missionary was murdered together with his two assistants. According to legend, he was murdered near Tenkitten (now Primorsk) in the Vistula Lagoon, not far from Königsberg (Kaliningrad) in the region known as East Prussia which is today under Russian control. He is said to have been murdered by a club or rowing oar. Others claim he was speared by a lance. A short time later, Bolesław Chrobry purchased the corpse from the murderers – legend has it that he had him weighed out in gold – and first buried him in the Benedictine abbey at Trzemeszno, about 15 kilometres to the east of Gniezno.

The close and trusting relationship between Adalbert and Otto III (980–1002) would be of long-lasting importance in Polish-German history. During that period, Otto III was the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. During the final years of his life, Adalbert served the young emperor as a father-like friend and as a spiritual advisor. Otto was deeply affected by the martyr’s death suffered by the missionary bishop and made great efforts to have him canonised by the Pope, who did so shortly afterwards in 999. The following spring, Otto embarked on a pilgrimage to Gniezno with a large retinue, where he arranged for reliquaries belonging to Adalbert to be interred in a specially endowed altar in the Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary (which later became the cathedral).

During the ceremonies that followed, Otto III bestowed the titles “frater et cooperator imperii” and “amicus populi romani” upon the Polish duke Bolesław Chrobry, thus raising his noble rank. This official “Act of Gniezno” is regarded as an important step towards the development of a Polish kingdom that was independent of the German “regnum”. Consequently, in 1025, Bolesław Chrobry had himself crowned Polish king after being elevated to that status. Through the establishment of the Archbishopric of Gniezno as a result of the Emperor’s visit, the Catholic Church of Poland was separated from the German church organisation and became independent.

As a result of the events of the year 1000, the City of Gniezno, its cathedral and the veneration of Adalbert had an extraordinary impact on the national psyche of the Polish people – and still do today. Even now, Adalbert figures and Adalbert windows grace numerous houses of worship from the Baltic Sea to the Carpathians; the archbishop of Gniezno also bore the title of Polish primate.

Ruhr Poles in Röhlinghausen

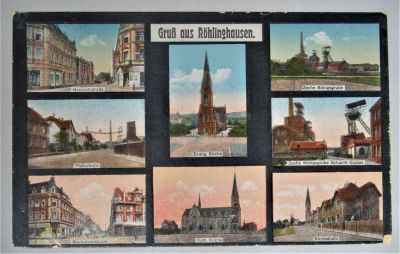

During the period of the German Empire (Kaiserreich), Polish immigrants brought their particular national style of Adalbert veneration to the Ruhr region. One impressive example of this is in Röhlinghausen, situated to the north-west of Bochum, which in 1926 was incorporated into the local district of Wanne-Eickel (and therefore, in 1975, into the district of Herne).

During the Industrial Revolution, Röhlinghausen experienced an extraordinary economic upturn. In 1806, just 117 people lived here; by 1830, that number had increased to 224. After the first deep mining shafts were sunk, the need for labourers to work the hard coal mine led to an enormous increase in the population after 1870 (in that year: 995). A large number of the immigrants were of Polish nationality. A census held on 1 January 1906 counted 11,733 inhabitants in total, of whom 4,731 were Poles and 1,334 Masurians. The Pluto-Thies and Königsgrube pits had a large proportion of Polish employees. Some miners’ settlements were inhabited almost entirely by Ruhr Polish families. In the local slang, the western end of Plutostraße was known as the “Polish cross-cut”.

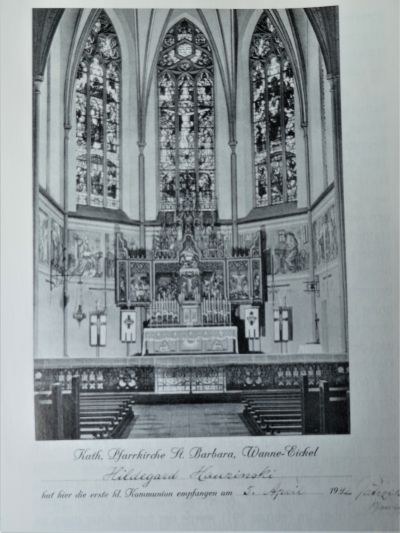

During the pre-industrial era, the few Catholics living in Röhlinghausen were members of the Holy Mary congregation in Eickel. Due to the high level of immigration, the Catholic community founded its own congregation in 1898. On the street then known as Moltkestraße, a modest makeshift church was built and consecrated in the name of Saint Barbara, the patron saint of miners. Soon, it became too small to accommodate the congregation, and in 1909–12, it was replaced by an impressive neo-Gothic hall church (architect: Herman Wielers, Wattenscheid). Once again, Saint Barbara was selected as the church’s patron.

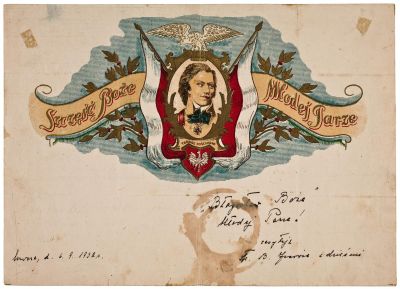

During the early years of the 20th century, between 20 and 35 percent of members of the church’s committees – the executive body of the church and the representatives of the local community – were of Polish nationality. Church associations were founded specifically with Ruhr Polish Catholics in mind. In Röhlinghausen, a “St. Adalbert Association” (St.-Adalbert-Verein) was established, which had 370 members in 1908, and which continued to exist until 1935. There is a registry entry from 1910 for the consecration of an association flag, and in 1912, an evening family event in remembrance of the priest Piotr Skarga (1536–1612), a well-known figure from the period of the Catholic Counter-Reformation in Poland, was documented.

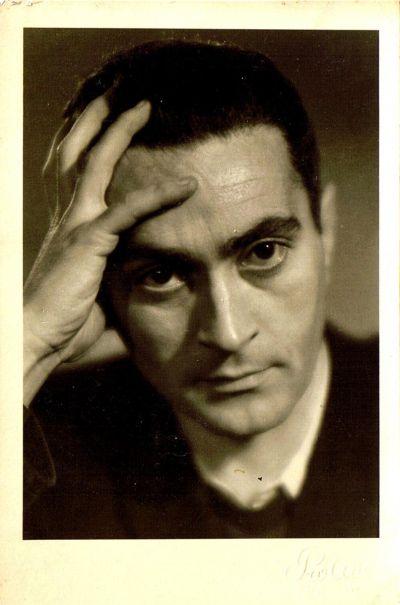

A stamp on a postcard from around 1912–1920, showing a group of people in formal dress in front of the portal entrance to St. Barbara, also mentions an association for Catholic Poles for Röhlinghausen. Only a few women can be seen on the postcard. Several men wear miners’ parade uniforms; for others, the head covering indicates membership in a national Polish organisation. The ceremonial nature of the meeting is underlined by the large number of flags. According to a label written in pencil on the rear side of the postcard, the occasion was a Polish festival of St. Mary (N.M.P., uroczystości Mariackie).

It is recorded that in many towns and villages in the Ruhr region, the Polish members of the community donated money for the construction of a church, or Polish associations donated furnishings and decorations for their house of worship, including a missionary cross (in Recklinghausen-Hochlarmark), a confession chair (in Oberhausen-Osterfeld) and an altar dedicated to St. Joseph (in Dortmund-Eving). There is no written record for donations of this nature in Röhlinghausen. However, the image of the Holy Adalbert on the high altar of the Church of St. Barbara lends credence to the assumption that the St. Adalbert association made a financial contribution.

The high altar in Röhlinghausen

The high altar was commissioned in 1908 and completed in February 1911. The congregation paid the fee of 15,000 reichsmarks in four tranches. The altar was produced collectively by three workshops from the “Wiedenbrück school” in the small town of Wiedenbrück in the eastern Münsterland region, (today: Rheda-Wiedenbrück). There, from around 1845–1945, over 25 companies produced a large number of historical altars, sculptures, stations of the cross and other furnishings, predominantly for Catholic houses of worship. The art workshops, which specialised in different crafts, complemented each other in the production of pieces, and often, individual workshops would collaborate directly with each other.

Production of the high altar in Röhlinghausen was managed by the Becker-Brockhinke cabinet makers, whose owner, Anton Becker (1862–1945) was also responsible for the overall design. The sculptor Anton Mohrmann (1851–1940) worked as a sub-contractor to produce the figures on the front side. The painter Eduard Goldkuhle (1878–1953) completed the colour frame and the partial gilding. He also produced the paintings on the outer sides of the two altar wings, which also show the Holy Adalbert. Mayor Schmitz of Wiedenbrück praised the product of this collaboration in 1923 as one of the most beautiful pieces that had ever left the Becker-Brockhinke workshop. During the 1980s, after the altar was restored, the Paderborn-based company Ochsenfarth described the oil paintings by Goldkuhle as being of the “highest neo-Gothic standard”.

In 1943, during the Second World War, an allied bombing raid destroyed the choir window of St. Barbara in Röhlinghausen. From then on, it became necessary to protect the high altar against weather damage by covering it with a large flag cloth. After three more bombing raids, it was finally removed from the damaged church and taken to Vinsebeck in the Weserbergland region. The altar returned to its original place after the church had been rudimentarily restored from 1945–48. 15 years later, a structural inspection found severe damage to the building caused by the mines below. On 31 December 1963, the church was closed by the building inspectors, and in the autumn of 1965, it was demolished. In 1968/69, a modern church was built on the same site which, being made from concrete, was immune to mining damage. Officially, the new building was consecrated in the name of the Holy Ghost, rather than St. Barbara. By that time, the patron saint of miners had been deleted from the Roman holy calendar during the course of the liturgical reform conducted by the Second Vatican Council, since her existence could not be historically proven. However, parts of the Catholic community – including in Röhlinghausen – refused to accept this decision. The congregation there still refers to itself as “Saint Barbara”.

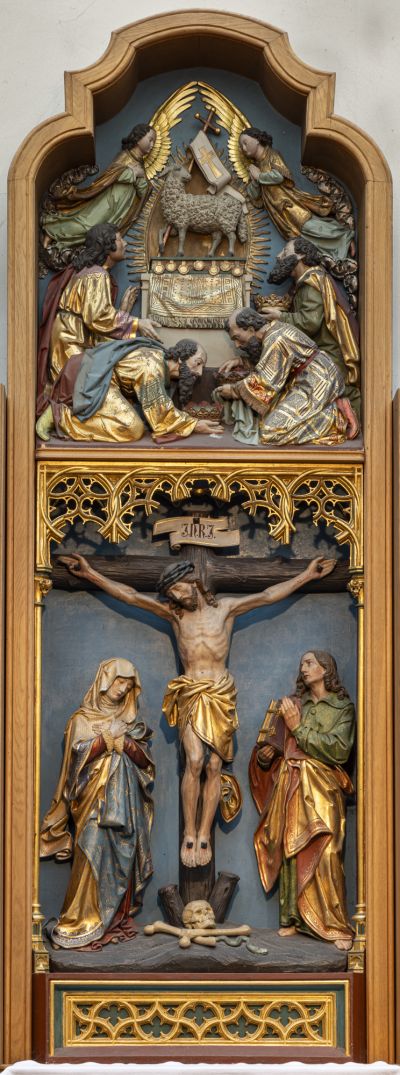

In the modern church in Röhlinghausen, a side chapel is dedicated to the popular patron saint of mining. The church also contains the high altar from the previous building, albeit in highly modified form. A new altar base has been created, into which a large piece of hard coal from the neighbouring pit known as “Our Fritz” (Unser Fritz) and a receptacle with a reliquary of St Barbara have been incorporated in order to keep the memory of the local mining tradition alive. In the central zone, two narrow panels are missing, which were originally added to the outer sides of the two altar wings. Higher up, it was necessary to remove the neo-Gothic superstructure, since the modern chapel was not high enough to accommodate it.

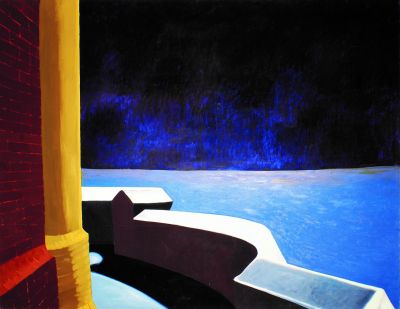

However, the central image panels have been retained! When folded out, the winged altarpiece shows carved scenes from the Bible. The central scene shows the crucifixion of Christ, and above it the appearance of the lamb from the apocalypse. On the left-hand side, the crucifixion scene is flanked by representations of the birth of Jesus and the wedding at Cana. The right flank shows the adoration of the Holy Three Kings and the transfiguration of Jesus on Mount Tabor. The lower altar zone contains four half-figures of prophets from the Old Testament.

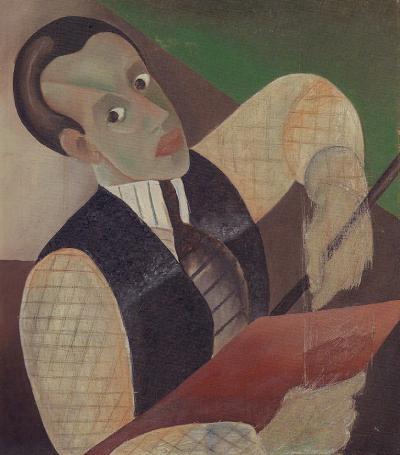

When folded closed, the winged altar shows two oil paintings, each with two holy figures: to the left, Cecilia and Bernhard, and to the right, Elisabeth and Adalbert. Adalbert wears a bishop’s mitre and mass robes. His right hand is raised in blessing. A bishop’s rod leans against his left shoulder. A club in his left hand is a reminder of the violent death suffered by the martyr.

To the left of Adalbert is the Holy Elisabeth, who lived from 1207–1231. In her right hand, she holds a loaf of bread, and in her left, a bowl with red roses. These two attributes stand for the “rose miracle”, a popular legend that tells of the selfless caritas of Countess Elisabeth of Thuringia: During a period of famine, Elisabeth had provided the poor of the town of Eisenach with bread from the Wartburg castle. She did not tell her husband, whom she unexpectedly met during one of her walks through the town, that she was offering help, saying instead that she was carrying roses with her, not bread. Before the count could check her baggage, God had miraculously turned the bread into roses.

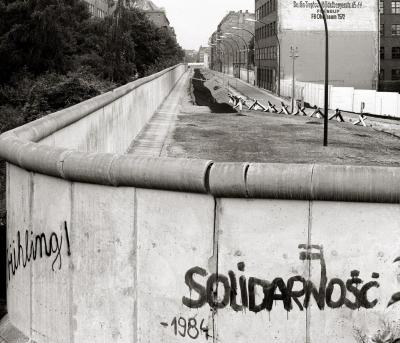

There is a particularly charming element in the Röhlinghausen juxtaposition: Bishop Adalbert of Prague became an important national saint in Poland, and also in the Ruhr region, due to the particular circumstances of his burial – the pilgrimage of Emperor Otto III, the raising of the rank of Bolesław Chrobrys, and the establishment of the archbishopric of Gniezno. Countess Elisabeth – who although she was born in Hungary, later did good deeds in Thuringia (in the “green heart” of Germany) – is also regarded as a kind of national saint in Germany. When one looks at the altarpiece, one cannot but view the painting as a symbol of Polish-German history. In this context, it is important to remember that in around 1900, there was considerable tension between the German- and Polish-speaking inhabitants of the Ruhr region. At that time, the authorities adopted various measures in order to pressure the Poles into becoming more German, at a cost to their national identity. The Catholic church was also called upon to support this process, which led to resistance and disputes in many church congregations.

Considering this political and social background, the altarpiece in Röhlinghausen can be interpreted as an appeal for a peaceful coexistence between people and ethnic groups of different nationalities. This appeal still resonates today – and not just in the “melting pot” that is the Ruhr region.

Thomas Parent, July 2023

Selected Bibliography:

Aus der Geschichte der katholischen Kirchengemeinde St. Barbara in Röhlinghausen 1886-1902, Herne o.J. [2002].

Große-Hovest, Benedikt: Die Firma Becker-Brockhinke. Eine Altarbauwerkstatt des Historismus, Aachen 1998.

Haida, Sylvia: Die Ruhrpolen. Nationale und konfessionelle Identität im Bewusstsein und im Alltag 1871-1918, phil. Diss. Bonn [masch.] 2012.

Parent, Thomas: Appell für ein friedliches Zusammenleben von Deutschen und Ruhrpolen. Anmerkungen zu einem Altarbild in der katholischen Kirche von Herne-Röhlinghausen, in: Der Emscherbrücher, Vol. 13 (2005/06), Herne 2005, p. 19–25.

Peters-Schildgen, Susanne: „Schmelztiegel“ Ruhrgebiet. Die Geschichte der Zuwanderung am Beispiel Herne bis 1997, Essen 1997.

Royt, Jan: Hl. Adalbert, Regensburg 1997.

Spieker, Brigitte und Rolf-Jürgen Spieker: In unvergleichlicher Pracht auf Goldgrund gemalt. Die Wiedenbrücker Maler Georg und Eduard Goldkuhle, Bramsche 2019.

![A festively dressed group in front of the portal entrance to St. Barbara of Röhlinghausen A festively dressed group in front of the portal entrance to St. Barbara of Röhlinghausen - Photo card, 1912 at the earliest [the year of the church's consecration]](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/Festliche%20Gruppe.jpg?itok=S2wHhY3t)