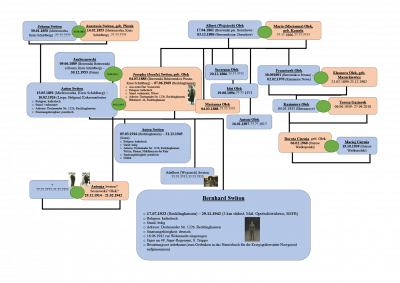

The death of a Polish Wehrmacht soldier in Russia: Bernhard Switon (1923-1942)

To this day, the attitude toward German military cemeteries in Russia is very divided. On the one hand, people are happy that the remains of German soldiers found near[18] them are being reburied, which also appears to be the best solution according to the Christian tradition of a “reasonable burial”. On the other hand, many people in Russia seem to find it disconcerting that the warmongers who attacked the country should be buried “honourably” in a cemetery in their country. This has to do with the fact that the commemoration of soldiers in Russia is equated with honouring the deceased as victors. For many decades, this attitude was characterised by the systematic idealisation of the victory in the Patriotic War[19] and of the honouring of soldiers as heroes. The “Soviet Russian culture of interpretation of the Great Patriotic War was, from the very start, arrogant and multifaceted, and yet it too was based on a central distinction: the distinction between the victors and the vanquished”[20] and so did not leave a lot of scope for classification into different groups of victims and perpetrators. Since the 1960s, the “heroical commemoration of the war”[21] has taken on greater significance among the general public in the Soviet Union and Russia. Right up to the present day, the remembrance of this war is seen as one of the most important events in Russian culture and is celebrated on several days of the year. “The public holidays which commemorate victory in the Second World War are still extremely important in Russia [...] 71.5 percent consider these days to be important which is why they are considered even more meaningful than Christmas, for example [...]”[22]. The significance of these celebrations is so great that the celebratory parade to mark the 75th day of the victory in the Patriotic War was not even cancelled during the coronavirus crisis of 2020, but was instead just moved from 9 May 2020 to 24 June 2020[23].

From this perspective, negotiations relating to the German memorial sites in Russia are proving rather difficult, which is evident from Russian newspaper articles online. In the articles about the cemeteries, the headings range from “Graves found in cellars” (Dnovec magazine, 2018) and “The 95-year-old former Wehrmacht soldier Hugo Bosse came to the Nowgorod region“ (53 Novosti, 2018), which show objective or positive representations of the war graves work, right up to “Russia’s body is covered with the abscesses of fascist memorials” (RVS, 2015) and “German War Graves Commission is preparing a pompous reburial ceremony under Volgograd” (SM News, 2019). The Commission rejects those accusations of a victory ceremony for German soldiers:

“Military cemeteries are not places where the dead are honoured but where they find their last resting place.”[24]

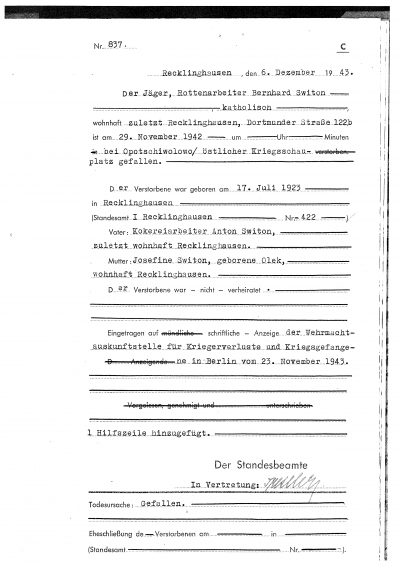

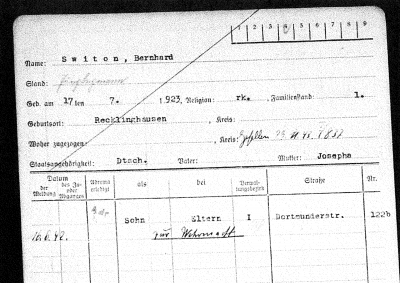

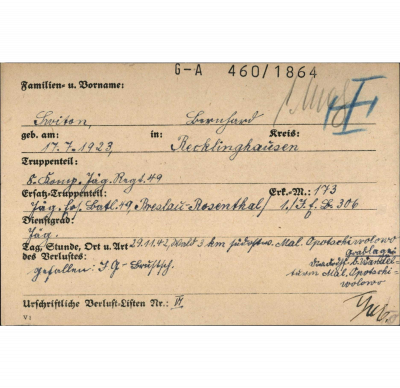

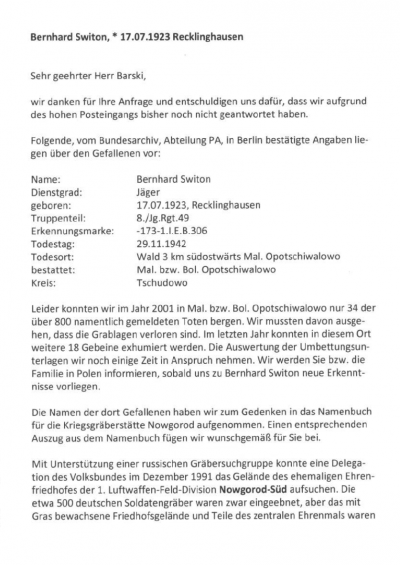

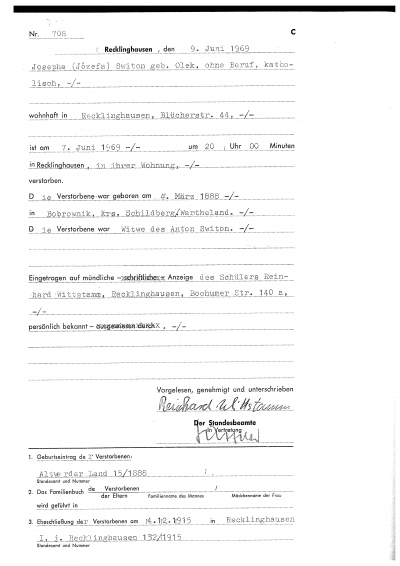

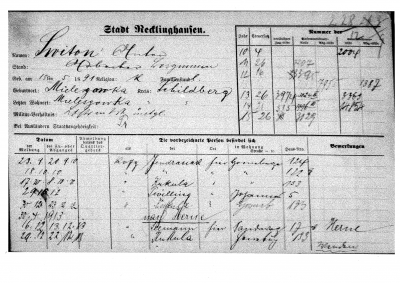

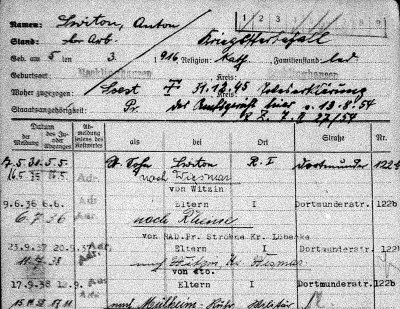

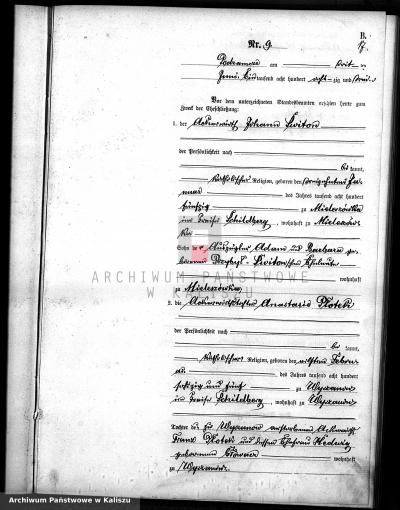

To avoid there being any perception at all that German soldiers are being honoured, the War Graves Commission is installing commemorative plaques with collective names and a few inscribed crosses in the cemeteries instead of individual gravestones. It is also notable that commemorative plaques have also been erected for Spanish and Flemish soldiers in the German military cemetery in Nowgorod, but Polish soldiers are not mentioned. This has to do with the fact that the Poles from the East who were conscripted into the Wehrmacht were mainly sent to the Western Front and those of Polish origin in the West were listed as German nationals in the military archives. It is also possible, however, that many of the Ruhr Poles were sent to the Eastern Front as many Polish surnames can be found in the extract from the War Graves Commission’s list of names relating to the Nowgorod cemetery. The documents do not reveal what fate befell the individual Wehrmacht soldiers in the territory of the Soviet Union. It is easy to imagine that there were many deserters, particularly among those soldiers who were forced to join the Wehrmacht. It cannot be ruled out that this was also Bernhard Switon’s position but our research did not reveal insights into his attitude towards the Nazi regime or about his activities on the Eastern Front or the exact cause of his death.

The subject of the participation of various players in the Second World War is also viewed critically in Poland in the context of the issue of guilt. This is why information about Donald Tusk’s grandfather being in the Wehrmacht[25] made headlines and why there was lot of fuss around Kaczmarek’s work “Polen in der Wehrmacht” [Poles in the Wehrmacht] because, according to Kaczmarek:

“[…] [there was ] little awareness for the fact that an ethnic German could also be a Pole in the ethno-cultural sense, who had been assimilated into the German “people’s community” under duress [...]. It was a shock to realise that ethnic Poles [...] served in the Wehrmacht in their droves not just in individual cases, particularly since there had been little doubt in Poland that the Wehrmacht was jointly responsible for war crimes.”[26]

[18] Even today, the remains of very many fallen soldiers still lie where they were temporarily buried during the war and on top of which houses, streets or parks have been built as time passed.

[19] The Great Patriotic War is the name given in Russia to the Soviet Union’s fight against Hitler’s Germany 1941-1945.

[20] Langenohl, Andreas. „Staatsbesuche: Internationalisierte Erinnerung an Den Zweiten Weltkrieg in Rußland Und Deutschland." Osteuropa 55, No. 4/6 (2005): p. 85. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44932726.

[21] Jahn, Peter: 22 June 1941: Kriegserinnerung in Deutschland und Russland (30.11.2011), in: http://www.bpb.de/apuz/59643/22-juni-1941-kriegserinnerung-in-deutschland-und-russland?p=all.

[22] Rüschendorf, Raphael Felix: Stalingrad im kollektiven Gedächtnis der Wolgograder Bevölkerung. Wie sich der Generationenwechsel auf die Erinnerung auswirkt (02.02.2017), https://erinnerung.hypotheses.org/1067.

[23] Moreover, the first parade after the Second World War was held in Moscow on 24 June 1945.

[24] Siegl, Elfie, p. 310.

[25] Only after the election campaign for the presidency in 2005 did it emerge that Donald Tusk’s grandfather had been in forced labour and concentration camps between 1939-42, before being conscripted into the Wehrmacht in 1943 after his release, and later managing to switch to the Polish Armed Forces (PSZ). Cf.: Kaczmarek, Ryszard, p. 16 f.

[26] Kaczmarek, Ryszard, p. 18.