Dora Diamant – activist, actress, and Franz Kafka’s last companion

For many years, little pieces of information from very specific periods in time were known about Dora Diamant. The writer Max Brod (1884–1968), Franz Kafka's close friend who later became the executor of his literary estate, knew of her existence no later than September 1923, when Kafka mentioned her in postcards and letters sent to Prague from the Steglitz district in Berlin. On 9 November, Brod travelled to Berlin to visit his lover, the actress Emmy Salveter, check up on Kafka’s state of health, and meet Kafka’s new girlfriend, Dora. From that time on, Dora always sent greetings to Brod. In a letter dated January 1924, she stressed that “I’d also like to write to Max”.[1] Kafka’s youngest sister, Ottla (1892–1943, Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp) and her husband, Josef David (1891–1962) knew about Dora by December 1923 at the latest, while Kafka’s parents regularly received news about her from January 1924, and also received notes and greetings from her in person. In his last letter to his parents, Kafka, whose tuberculosis had spread to his larynx in the spring of 1924, wrote on the day before he died of the “help given by Dora, which from a distance is wholly unfathomable”.[2] Dora Diamant was also regularly mentioned in Kafka’s letters to the young Tile Rössler (Tehila Ressler, 1907–1959), who lived with her parents in Berlin and who would later become a dancer, to his previous lover Milena Jesenská (1896–1944, Ravensbrück concentration camp), to the elocutionist and reciter Ludwig Hardt (1886–1947), and to his friend Robert Klopstock (1899–1972), who together with Dora cared for Kafka until his death.

Dora Diamant recounts her life with Franz Kafka

Diamant publicly spoke about her life with Kafka for the first time just over two years after the end of the Second World War. In London, Dora Dymant, as she called herself after her move to England, and the painter Friedrich Feigl (1884–1965), a fellow pupil of Kafka’s in Prague, were interviewed by the author and art historian Josef Paul Hodin (1905–1995). Originally from Prague, Hodin was a graduate of law, biographer of the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch, and press attaché of the Czechoslovak government in exile in London. Feigl, who had lived with his wife in Berlin since 1910, had met Kafka there again, together with Dora Diamant. Hodin turned the two interviews into a long essay, “Memories of Franz Kafka”, which appeared in the monthly London literary journal “Horizon – A Review of Literature and Art” in January 1948. In June 1949, a German version was published in Berlin in the US military government magazine “Der Monat”, an “international journal for politics and intellectual life”.[3]

Feigl, who had attended the German-language grammar school, the Deutsches Altstädter Gymnasium in Prague together with Kafka, and who had subsequently studied at the Prague Academy of Fine Art, told Hodin that Kafka had introduced him to his fiancée, Dora Diamant, in Berlin and that he had purchased one of his pictures, a somewhat sinister study of Prague, which Kafka had given to Diamant as a gift.[4] Hodin wrote that he had spent many hours with Ms Dora Dymant, during which time they had talked about Kafka and the final months of his life. She had conceded that it was not possible to be objective more than 20 years following Kafka’s passing. “But after all, one can only measure time by the importance of one’s experiences. Even today it is often difficult for me to talk about Kafka. Frequently it is not the facts which are decisive, it is a mere matter of atmosphere. What I tell has an inner truth. Subjectivity is part of it.”[5]

In the interview, Diamant spoke of the first time she met Kafka, whom she first noticed on the beach in Müritz in the company of his sister Elli (1889–1942, Kulmhof death camp) and her two children, Gerti and Felix. Kafka’s presence made an impression on her, and she followed them into the town. That evening, she saw him again in the “Haus Huten”, the holiday home of the Jüdisches Volksheim, where Dr. Franz Kafka from Prague had been invited to dinner as the guest of honour. The large, two-storey lodging house on the edge of the birch forest to the east of Müritz[6] was situated within sight of the “Landhaus Glückauf”, where Kafka was living. She described his manner of behaviour and his character, their life together later on in Berlin, the idiosyncrasies of his writing process, his everyday habits and quirks, gave information about the writers and publicists who came to visit him, such as Franz Werfel (1890–1945), Willy Haas (1891–1973) and Rudolf Kayser (1889–1964)[7], as well as the literature he loved, including Kleist’s “Marquise von O.” and Goethe’s “Hermann und Dorothea”. She talked about his departure from Berlin to live with his parents in Prague for health reasons, his admission to sanatoriums in Lower Austria and Klosterneuburg, and about his death.

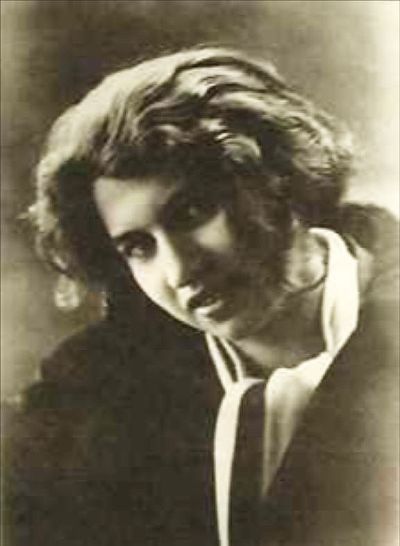

She gave only scant information about herself. She said that she had come “from the east”, “as a dark creature full of dreams and premonitions, as though sprung from a novel by Dostoevsky”. She had heard so much “about the west, about its knowledge, its clarity and its way of life”. After the end of the First World War, she travelled “to Germany with a receptive soul”. “After the catastrophe of the war, everyone expected salvation to come from the east. I, however, ran away from the east, because I believed that the light came from the west. [...] In the east, there was a knowledge about mankind; it may have been impossible to move so freely about in society, and to express oneself so easily, but there was an awareness of the unity between mankind and creation. When I saw Kafka for the first time, his appearance immediately fulfilled my mental image of mankind”.[8]

[1] Letter from Franz Kafka to Max Brod, Berlin-Steglitz, arrival postmark Praha-Hrad, 14/1/1924, in: Max Brod, Franz Kafka – eine Freundschaft. Volume 2: Briefwechsel, Frankfurt/Main 1989. Letters of Franz Kafka from various sources can be accessed on the website of ADir. Werner Haas (University of Vienna) via a search function: https://homepage.univie.ac.at/werner.haas/ (last accessed on 04.08.2023). – Max Brod, who had graduated as a lawyer and who was a respected novelist in his own right, worked as an official at the central post office in Prague until the spring of 1924, then as an art and literary critic at the “Prager Tagblatt” newspaper. Dora Diamant addressed postcards written by Kafka to Max Brod dated 20/4 and 28/4/1924 to the postal address of the “Prager Tagblatt”.

[2] Letter from Franz Kafka to his parents, Kierling, Dr. Hoffmann’s Sanatorium, 2/6/1924, in: Franz Kafka. Briefe an Ottla und die Familie, published by Hartmut Binder and Klaus Wagenbach, Frankfurt/Main 1975; also in: Brod 1962 (see Bibliography), page 257 f.

[3] Hans-Gerd Koch wrote a summary of the German translation of the interview from “Der Monat” under the author’s name Dora Diamant, entitled “Mein Leben mit Franz Kafka” (“My life with Franz Kafka”), and re-published the article in 1995 in his collected volume “Als Kafka mir entgegenkam ...” (see Bibliography), page 174–185. Klaus Wagenbach 1964 [10th edition 1972, see Bibliography], page 146, quotes another version under the name Dora Dymant, entitled “Ich habe Franz Kafka geliebt” (“I loved Franz Kafka”), from: “Die Neue Zeitung”, 18/8/1948. This newspaper was released in Munich from 1945 onwards, and later appeared with its own edition in Berlin as “an American newspaper for the German people”, published by the US Army; see Bernhard von Zech-Kleber: Die Neue Zeitung, at: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns, https://www.historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de/Lexikon/Die_Neue_Zeitung (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[4] Hodin 1948 (see Bibliography), page 32–34.

[5] Ibid., page 35.

[6] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 26.

[7] The literary historian Rudolf Kayser had been the editor of the Berlin literary journal “Die neue Rundschau” since 1922. The October edition of that year included Kafka’s novella A Hunger Artist (Ein Hungerkünstler). In the July volume of 1924, Kayser wrote an obituary of Franz Kafka (Volume 35, Vol. 2, book 7, page 752); re-printed in the collected volume of Hans-Gerd Koch: “Als Kafka mir entgegen kam …” 1995 (see Bibliography), page 196 f.

[8] Dora Diamant: Mein Leben mit Franz Kafka 1995 (see note 3), page 175.

Friends and acquaintances describe Kafka and Diamant

Diamant’s account is supplemented by the reminiscences of Tile Rössler, who was 16 years old at the time, and who had also fallen in love with Kafka in Müritz. In August 1923, she wrote a letter from Müritz to Kafka in Berlin. Her account was recorded by the Austrian writer Martha Hofmann (1896–1975).[9] Tile, born in 1907 as Tehila Ressler in Tarnów in Lesser Poland, in Austrian-ruled Galicia, fled to Berlin with her parents at the outbreak of the First World War. There, she worked as a young trainee in the Jurovicz bookshop in the city, not far from Alexanderplatz. In July 1923, she was also staying at the Jewish holiday home in Müritz. She had already heard of Kafka, having placed a copy of his short story “The Stoker” (Der Heizer, 1913) in the shop window of the bookshop herself. Kafka noticed Tile during a theatre performance given by the children staying in the home and invited her to join him on his wicker beach chair. As she later reported, Tile returned the gesture with an invitation to join them for an evening at the Volksheim. It was there that she introduced Kafka to Dora, who was the kitchen manager there. When Kafka took Tile to a performance of Schiller’s play “The Robbers” (Die Räuber) in the Schauspielhaus theatre after he returned to Berlin, she thought that her hopes for a closer relationship with the famous writer would be fulfilled. Therefore, when Kafka invited her to his apartment in Steglitz, she was all the more disappointed to find Dora there, who was now his partner.[10]

The French essayist, respected Kafka specialist, and Kafka translator Marthe Robert (1914–1996) also remembered Dora Diamant. Three months after Diamant’s death, she published an obituary in the Paris journal “Évidences”, the monthly magazine of the American Jewish Committee. Ten months later, the short text was re-printed in German translation in the monthly culture journal “Merkur. Deutsche Zeitschrift für europäisches Denken”[11]. Robert, who described Diamant as reclusive, with "gloomy" living conditions in London, knew of just one earlier interview, which had been published two years previously by the editor of “Évidences”, the Hungarian-born French journalist and activist Nicolas Baudy (real name Miklos Neumann, 1907–1972). Baudy had interviewed Diamant on topics such as Kafka’s Hebrew lessons and his relationship to Judaism and Zionism.[12] According to Robert, Diamant consistently responded with a clear “No” to repeated questions as to whether Kafka “believed”, in other words, whether he was religious.[13] Robert reported that Diamant had begun to record her memories of Kafka in writing at the start of her own illness. However, Robert’s plan to publish these records never came to fruition.

She quoted word-for-word Diamant’s description of her first meeting with Kafka in Müritz. In particular, however, she made it known for the first time that decades after Kafka’s death, Diamant, who was in exile in London, felt that it was her “calling” to save the Yiddish language from extinction. “In her eyes, Yiddish poetry and literature were the only part of the truth that she could preserve and pass on to others”. She organised lecture evenings, meetings, readings, and theatre performances: “She recited, played, sang, and encouraged others to sing with her – in front of an audience whose connection to old, almost forgotten emotions was reawakened by her. She developed the extraordinary acting skills that she had not wished to develop in the theatre. This passion was engendered within her by the end of Jewish Poland, the Poland from which she, like so many others, had fled in her youth, and yet which she had never really left behind”. According to Robert, she cast her own light onto the world around her. Just as she had radiated it onto Kafka, so “she also spread light onto her environment in the Jewish milieu of Whitechapel, which had become her adoptive home”.[14]

Brod, Kafka’s friend since they had studied together in Prague in 1902, was a supporter, mentor, and collector of Kafka’s literary work, as well as the publisher of his extensive literary estate, including the three major novels “The Castle” (Das Schloss), “The Trial” (Der Prozess), and “America” (Amerika). His biography of Kafka, which was first published in Prague in 1937, and later in 1962 by S. Fischer Verlag in Frankfurt/Main, contains 21 pages of information about Dora Dymant, which has since then been repeatedly re-used elsewhere. In Brod’s view, as he wrote in the chapter “The Final Years”, for Kafka “happiness did come his way [...], and the outcome of his fate was more positive and more full of life than its whole previous development” with his final partner.[15]

[9] Martha Hofmann, a poet, writer, teacher and Jewish activist who was born in Vienna, had probably received the account, together with Kafka’s letter, from Tile Rössler (Tehila Ressler) in around 1940 in Palestine, and subsequently published the novella “Dinah and the Poet” in Hebrew, which centred around Rössler’s meeting with Kafka, in 1942. In 1954, in the Viennese weekly journal “Die Österreichische Furche” (see Bibliography), she revealed that “Dina” was Tile Rössler, again discussed her account, and as an appendix published Kafka’s letter to “My dear Dinah”, or “My dear Tila”, dated Müritz, 3/8/1923 and addressed to the Jurovicz bookshop in Berlin C 2, https://homepage.univie.ac.at/werner.haas/1923/br23-017.htm (last accessed on 4/8/2023). According to Yonat Rotman in 2011 (see below, note 10), the letter is now held in the archive of the Beit Ariela Library in Tel Aviv. In 1995, Hans-Gerd Koch again published Martha Hofmann’s article under the name Tile Rössler, entitled Meeting in Müritz (Begegnung in Müritz), in his collected volume “Als Kafka mir entgegenkam …” (see Bibliography), page 168–173.

[10] From 1925, Tile Rössler/Tehila Ressler trained as a dancer in Mannheim with Irmgard Meyer, a pupil of the choreographer and dance teacher Mary Wigman. She then studied with Wigman herself in Dresden, and also at the dance school founded by Gret Palucca in 1925. Palucca and Rössler had a close relationship. From 1930, Rössler worked as a teacher and school director at the Palucca School. In 1933, she and all other Jewish employees at the school were dismissed as part of the National Socialist “coordination policy” (“Gleichschaltung”). She emigrated to Palestine, where she founded her own dance school, the Tehila Ressler School, in Tel Aviv. In 1943, she established a teacher training programme at her school. The first female pupil was the Israeli dancer, dance teacher, choreographer and textile artist Noa Eshkol (1924–2007). Ressler died in Tel Aviv in 1959. On Tile Rössler/Tehila Ressler, see: Biographisches Lexikon der Theaterkünstler (Frithjof Trapp et al, publisher: Handbuch des deutschsprachigen Exiltheaters 1933–1945, Volume 2), Munich 1998, page 788; Yonat Rotman: Three letters to Tehila Rössler, in: Mahol Akhshav-Dance Today, No. 21, 2011, page 69–71, https://www.israeldance-diaries.co.il/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/DT21_Three_letter_to-Tehila.pdf (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[11] Robert 1952 and Robert 1953 (see Bibliography)

[12] Baudy 1950 (see Bibliography); a copy of the journal can be found in the National Library of France in Paris. See also Iris Bruce: Der Proceß in Yiddish, or The Importance of being Humorous, in: Traduction, terminologie, rédaction (TTR), Volume 7, No. 2, Québec 1994, page 41.

[13] Robert 1953 (see Bibliography), page 239.

[14] Ibid., page 848.

[15] Brod 1962, English language edition (see Bibliography), page 196.

According to Brod, Dora Dymant “came from a very well-regarded Polish Orthodox Jewish family. For all the respect she bore for her father, whom she loved, she could not stand the constraint, the narrowness of the tradition [...] Dora escaped from the little Polish town, and found jobs first in Breslau, then in Berlin, and came to Müritz in the employ of the Home. She was an excellent Hebrew student. Kafka was studying Hebrew with special zeal at that time. [...] One of the first conversations between the two ended in Dora’s reading aloud a chapter from Isaiah in the original Hebrew. Franz recognised her theatrical talent; following his advice and under his direction, she later educated herself in this art”.[16]

Fresh back from his summer holiday in Müritz, Kafka decided to “cut all ties [to Prague], get to Berlin and live with Dora”.[17] For the first six weeks, the couple lived on Miquelstraße in Steglitz. Since their landlady, Frau Hermann, immortalised by Kafka in his story “A Little Woman” (Eine kleine Frau, 1924), constantly created difficulties for the young, unmarried Jewish couple, they moved into two rooms on Grunewaldstraße shortly afterwards. Brod continues: “There I went to see him as often as I came to Berlin – three times it must have been in all. I found an idyll; at last I saw my friend in good spirits; his bodily health had got worse, it is true. [...] Franz spoke about the demons which had, at last, let go of him. ‘I have slipped away from them. This moving to Berlin was magnificent, now they are looking for me and can’t find me, at least for the moment.’ He had finally achieved the ideal of an independent life, a home of his own, he was no longer a son living with his parents, but to a certain extent himself a paterfamilias. [...] In this sense I saw Kafka on the right road, and truly happy with his life-companion in the last year of his life, which, despite his frightful illness, perfected him.”[18]

The external circumstances in which the couple lived were dominated by the rampant inflation during the winter months of 1923. Dora is quoted as saying that when Kafka came home after buying purchases in the centre of Berlin, it was “as if he were coming back from the battlefield”. Both suffered great privations. Brod writes that Kafka insisted on making do with his tiny pension: “Only in the worst case and under great pressure will he accept money and parcels of food from his family. [...] There is a shortage of coal. Butter, he gets from Prague”. Even so, he requested “gift parcels” for acquaintances in need, which contained only what was absolutely necessary for survival: “Now live a few days longer on groats, rice, flour, sugar, tea and coffee, and then die as best you can, we can’t do any more for you”. Between Christmas and New Year, Kafka was plagued by severe attacks of fever. Even so, febrile as he was, he and Dora moved to the district of Zehlendorf: “He lived a retired life. Very seldom visitors came from Berlin: Dr. Rudolf Kayser, Ernst Blass”.[19]

Kafka had plans to move to Palestine and together with Dora, “who was such an excellent cook”, to open a restaurant where he would make himself useful as a waiter. In one of the Berlin apartments, Dora, as she later told Brod, burned several of Kafka’s manuscripts at his request: “He commanded it, and, shaking, she obeyed him. Even many years later, she still had regrets that she had complied. She stressed the fact that even today, when presented with the same situation, she would have bowed to Kafka’s will. […] Other documents belonging to Kafka that remained with Dora were seized by the Gestapo after 1933 and were evidently destroyed”.[20]

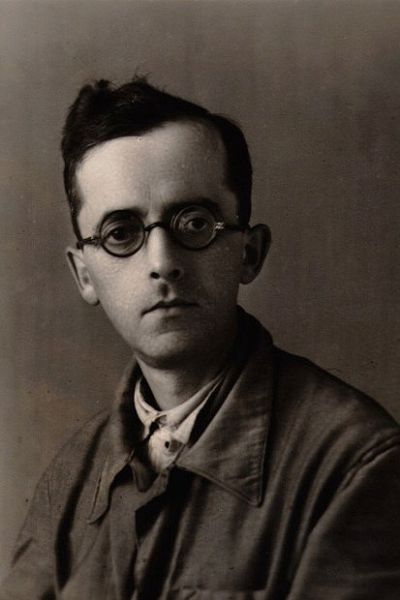

On 17 March 1924, Brod accompanied Kafka, who by now was severely ill, to Prague, after Dora and Robert Klopstock had taken him to the railway station in Berlin. Klopstock was a medical student from Hungary who himself had fallen ill with tuberculosis during the First World War, and with whom Kafka had become acquainted at the start of 1921 in the sanatorium in the Slovakian health resort Tratranské Matliare.[21] According to Brod, Dora arrived several days later. After spending time along the way with his parents in Prague and in the Sanatorium Wienerwald in Feichtenbach in Lower Austria, Kafka was moved to a clinic in Vienna with laryngeal tuberculosis. “The only car to be had from the sanatorium to Vienna”, Brod reports, “was an open one. There was rain and wind. The whole journey through, Dora stood up in the car, trying to protect Franz with her body against the bad weather”. Dora and Klopstock, now referring to themselves “playfully as Franz’ ‘little family’”, devoted themselves entirely to his care, and finally succeeded in having him transferred to the friendly, light-filled Sanatorium Hoffmann in Kierling near Klosterneuburg.

During the following weeks, Kafka, who was now almost unable to speak or swallow food, found new courage. “He wanted to marry Dora”, Brod writes, “and had sent her pious father a letter in which he explains that, although he was not a practising Jew in her father’s sense, he was nevertheless a ‘repentant one, seeking to return’ and therefore might perhaps hope to be accepted into the family of such a pious man”. The father set off with the letter to Gerrer Rebbe, the highest authority in the Hasidic community, who read the letter, put it on one side, and said “No”. For Kafka, the father’s letter of response was a “bad omen”.[22] On the last day of his life, Kafka worked on corrections for his last book “A Hunger Artist” (Ein Hungerkünstler, 1924) and provided instructions for changing the order of the stories. At four o’clock on the following morning, Kafka's state became critical. Dora was the first to notice and the only way of providing any kind of relief was by administering morphine. Kafka died on 3 June 1924, with Diamant and Klopstock at his side.

[16] Ibid., page 197.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid., page 198.

[19] Ibid., page 201–202.

[20] Brod, 1962, German language edition 247 f. (translated from the German). On 8 March 1933, the documents belonging to Kafka were seized by the Gestapo from the apartment of Lutz and Dora Lask in Pariserstraße 13 in Berlin-Wilmersdorf. They included diary entries, 35 letters addressed to Dora and 20 manuscript notebooks. They were kept in the Gestapo archive, were probably taken to Moscow in 1945 with the stock of documents held by the Gestapo and were returned to the GDR during the 1950s. There, they were stored in the Ministry for State Security, and are lying unidentified in what is likely to be an enormous stock of unseen files in the German Federal Archive (Bundesarchiv); see Hans-Gerd Koch: Franz Kafka. Der unbekannte Aktenberg, in: “Süddeutsche Zeitung” dated 6/12/2019, https://www.sueddeutsche.de/kultur/kafka-bundesarchiv-gestapo-akten-1.4711090 (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[21] For a biography of Robert Klopstock see also: Robert Klopstock – Kafkas letzter Freund, at: PragToGo, https://prag-to-go.com/kafka-in-prag/themen/familie-und-freunde/robert-klopstock-kafkas-letzter-freund (last accessed on 04.08.2023). See also Robert Klopstock: Mit Kafka in Matliary, in the collected volume of Hans-Gerd Koch: “Als Kafka mir entgegen kam …” 1995 (see Bibliography), page 153–156.

[22] Brod 1962, English language edition (see Bibliography), page 208.

Finally, researchers are taking an interest in the topic

In the two decades that followed the publication of the Frankfurt edition of Brod’s Kafka biography, no-one appeared to be interested in filling in the missing years in Dora Diamant’s life. It was thought that the period before her first meeting with Kafka in Müritz and the 28 years after his death had nothing to contribute to the ever-increasing amount of literature about the writer.[23] Finally, in 1984, the German-American translator and biographer Ernst Pawel (1920–1994), who was born in Breslau/Wrocław, added details of Diamant’s life after the late 1920s in his award-winning Kafka biography “The Nightmare of Reason”. He wrote that during this time, she married a prominent leading member of the German Communist Party (Deutsche Kommunistische Partei) and had a child with him. In February 1933, several days after the National Socialists seized power, her husband fled abroad. He managed to escape just in time before a manhunt was conducted by the Gestapo and their shared apartment was searched. During the search, papers originally belonging to Kafka were confiscated. Pawel continued that a short time later, Diamant left Germany with her child and moved to Moscow. Her husband was arrested in the Soviet Union, Pawel wrote, then convicted as a Trotskyist saboteur and deported to Vorkuta. She never heard from him again. After her daughter fell ill with a kidney disease, Pawel wrote that Diamant was granted permission to leave for England in 1938, where Diamant’s daughter remained after Diamant’s death in 1952.[24]

Pawel also quoted from a letter from Diamant to Brod in May 1930 from Berlin-Charlottenburg, which Brod had already published in 1966 without further comment, and in which she described her ambivalent relationship to Kafka’s literary work and the planned publication of his estate: “As long as I was living with Franz, all I could see was him and me. Anything other than him was simply irrelevant and sometimes ridiculous. His work was unimportant at best. Any attempt to represent his work as part of him seemed to me simply ridiculous. That is why I objected to the posthumous publication of his writings. And besides, as I am only now beginning to understand, there was the fear of having to share him with others. Every public statement, every conversation, I regarded as a violent intrusion into my private realm. [...]”[25]

At this time, in May 1930, Diamant had still kept hidden the fact that after Kafka’s death, she had withheld a significant number of his manuscripts and letters, which ultimately led to their being lost when they were seized by the Gestapo. Here, too, Brod had already stated earlier that Diamant had been forced to admit in the end that this was the case. Following the seizure of a portion of Kafka’s estate “from Mrs Dora Dymant”, he, Brod, asked Camill Hoffmann (1878–1944, Auschwitz concentration camp), the press attaché of the Czechoslovakian Embassy in Berlin, to “look into the matter and to intervene”: “This time, his efforts were in vain. Soon, he himself vanished into the storm of the times [...] Auschwitz? We can assume that Kafka’s Berlin estate is lost”.[26]

In the mid-1980s, the theatre scholar Kathi Diamant (*1952), who now lives in San Diego, California, began intensive research into Dora Diamant’s life. She had already discovered the existence of the woman who shared her name while studying German literature in 1971. After reading Pawel’s biography of Kafka, she travelled to Poland, Germany, France, Britain, Czechoslovakia, and Israel to conduct research. Her work took her to public libraries such as the Pabianice City Museum (Muzeum Miasta Pabianic) and the local registration office (Urząd stanu cywilnego), where she found Dora’s birth certificate, to the Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History in Moscow, where Dora Diamant’s Komintern file is held, the Archives of the Political Parties and Mass Organisations of the GDR Foundation (Stiftung Archiv der Parteien und Massenorganisationen der DDR), to the Federal Archive (Bundesarchiv) in Berlin and the Berlin State Archive (Landesarchiv), which contains Gestapo files on Dora and the Lask family, and to the Düsseldorf City Archive (Stadtarchiv Düsseldorf), where the registration document and residence permit of Dora Diamant are stored. In private collections, she found letters from 1941 and 1951/52, among other items, and in the estate of Marthe Robert in France, the “diary” that was intended as the basis for Diamant’s “memories” of Kafka, which were never published. In the Archiv Klaus Wagenbach, she found a duplicate copy of the “diary”, together with texts, notes and letters from the time of Dora Diamant’s illness and death.[27]

In 2003, Kathi Diamant published the biography, which was around 400 pages long, in New York. In “Kafka’s Last Love. The Mystery of Dora Diamant”, she made the “diary” and other chronological notes available to the public for the first time. Her book was translated into Spanish, French, Chinese, Russian, and Portuguese. The German version did not appear until a decade later. It contains a transcription of Dora Diamant’s notes from the original German documents, with the addition of facsimile photographs.[28] Not included are 70 letters from Dora Diamant to Max Brod, which were not accessible due to a legal dispute surrounding Brod’s estate in storage in Israel that ran from 2005 onwards. In 2016, the estate was awarded to the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem and has been available for access since 2019.[29]

[23] The literary scholar and Kafka biographer Reiner Stach (*1951) points out that wives of famous men were traditionally assigned the “honorary task” of “kindling the male spirit and providing sensual fuel”: “‘The genius and his muse’ is a topos of more recent European cultural history, and in terms of ideology is one of the most persistent: even in the 20th century, when the concept of genius has already long been rendered obsolete”. The same, he writes, is true of “Felice, Milena, Dora”, “women, therefore, with whom Kafka had an important erotic relationship, and who we know influenced his literary work”. While a huge bundle of letters has been preserved from Felice Bauer, Kafka’s first fiancée, his “Letters to Milena”, to Milena Jesenská, which were published in 1952 by Willy Haas, sound almost like the title of a work of literature. As a result, these women are regarded as “mere projection surfaces”. “As regards Dora Diamant, no-one had any idea who she was, except that she must have been an extraordinary piece of luck for the severely ill Kafka. It was not until the end of the last century that palpable frustration arose among researchers and the general public alike that we were still being presented with faceless muses. Now, there is an increased awareness of the fact that this could in no way have been what Kafka would have wanted. After all, the people to whom he was close, whom he had in a certain sense chosen, certainly were of importance to his life – never mind the fact that these women also became interesting in their own right”. (Foreword by Reiner Stach, in: Kathi Diamant 2013, German language edition (translated from the German) (see Bibliography), page 17 f.

[24] Pawel 1984 (see Bibliography), page 438 f.

[25] In Pawel 1984 (see Bibliography, page 438) English-language publication. Quoted in the German original from Max Brod: Der Prager Kreis, Stuttgart et al.: Kohlhammer, 1966, page 113.

[26] Max Brod: Streitbares Leben 1884–1968, Munich et al.: F. A. Herbig, 1969, page 14 f.

[27] Foreword to the first German language edition (translated from the German), in: Kathi Diamant 2013, see Bibliography, page 13 f.; sources, ibid., page 441–443.

[28] Foreword to the German language edition (translated from the German), in: Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 15 f.

[29] Tim Aßmann: Max-Brod-Nachlass in Israel. Kafkas Vokabelheft, on: Deutschlandfunk radio, 7/8/2019, https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/max-brod-nachlass-in-israel-kafkas-vokabelheft-100.html (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

A Jewish life story between Poland and Germany

According to the birth certificate in the registration office in Pabianice, Dworja Diament was born on 4 March 1898, the daughter of Hersz Aron Diament and Frajda Fridl Diament, aged 24 and 25 respectively. In Yiddish, her father’s name was Herszel (Hebrew: Zvi) Aron Lizer Dymant. His wife was known by the Yiddish name Friedel. The earliest records go back to a weaver, Szlama Efroim Dymant, who was born in 1827 in Brzeziny, a few kilometres to the east of Łódź. Twenty years later, he moved to Pabianice with his young family, where weavers and tailors were resettled in order to support the expansion of the cotton industry. Herszel Dymant, who was probably his grandson, and Friedel had a son, David, in 1897. He was followed by Dworja (or Dora), then Jakub, a sister, Nacha, then Abram and another son, Arje. In 1905, the same year as the birth of her youngest son, Dora’s mother died.[30] As the eldest daughter, Dora was assigned the task of taking care of the household and of her siblings.

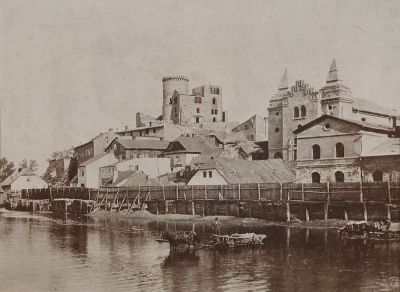

After the death of his wife, Herszel moved to Będzin with the children. There, the family lived in ulica Modrzejowska, in the area between the castle ruins and the great synagogue (Fig. 1), where he ran a successful workshop for suspenders and garters. He was educated, had an extensive library, spoke Polish, German, Yiddish and Hebrew, and was one of the most respected residents in the town. He wore a traditional kaftan, with a beard and sidecurls, was the head of the local Hasidic community under the Rebbe of Ger (Góra Kalwaria) and was responsible for the house of prayer. On the Sabbath, members of the community came to his home, while he dedicated himself to supporting poor families. He did nothing without the approval of the incumbent Gerrer Rebbe, Avraham Mordechai Alter (1866–1948), who in turn referred to “Herszel the Paviancer” – Herszel from Pabianice – as his “diamond”. While at the end of the 19th century, Będzin had the seventh-largest Jewish community in the Kingdom of Poland, with around 11,000 members making up 45 percent of the population of the district mining town,[31] the Gerrer Hasidim dedicated themselves to the study of the Talmud, forbade any kind of reform or modernisation that was not prescribed in the Torah, and opposed the Jewish reformist movements.

Even though in Russian-ruled Congress Poland there was no mandatory schooling for children up to age 14, Dora was permitted to attend Polish schools. For girls, who according to the Jewish laws were not allowed to study the Talmud, a general school education improved their “prospects on the marriage market”. Nevertheless, Dora’s father did not marry her off early, probably because of her duties in the family household.[32] Eager to obtain an education, she joined Hebraica, an organisation founded by Zionist groups in Będzin during the course of the First World War. Based on the first Zionist movement established in 1881, Chibbat Zion, the ideas of Theodor Herzl (1860–1904) and the first Zionist World Congress of 1897, the organisation propagated the founding of a Jewish state and the dissemination of Hebrew as the national language. Although the religious community led by Gerrer Rebbe threatened the parents of the pupils of the organisation, who came from all political and social layers of Jewish society, with exclusion from the congregation, Dora enrolled for courses in Hebrew. The courses offered to girls and women who wanted to teach their children Hebrew were given by the Będzin-born writer David Maletz (1899–1981), one of the later founding members of the Kibbutz En Charod in Palestine, who had studied at a Talmud university (Fig. 2).[33] In addition, Dora joined a theatre group, which according to Kathi Diamant’s account was regarded by the “ultraorthodox religious groups” as a “desecration of the Holy Scripture”.[34]

After remarrying in 1918 and fathering more children with his new wife, Herszel Dymant brought Dora to Krakow, where she was to receive training as a kindergarten teacher at the Beis-Ya’acov School (Szkoła Beis Jaakow). This school, which was founded in 1917 by the Polish-Jewish teacher Sara Szenirer (Sarah Schenirer, 1883–1935), and which was followed by other schools that were established worldwide, was supported by Hasidic rabbis such as Gerrer Rebbe, and aimed, for the first time, to provide young Orthodox women with a higher school education while at the same time protecting them against secular influences and assimilation into Polish society. According to Dora’s own account, it was here that she perceived herself for the first time as being a “thinking, aware person”.[35] Nevertheless, she felt so uncomfortable among her fellow pupils that she secretly packed her suitcase and fled to Breslau in Prussia, where acquaintances of hers lived. Her father found out her whereabouts, and brought her first back home, then back to the school in Krakow.

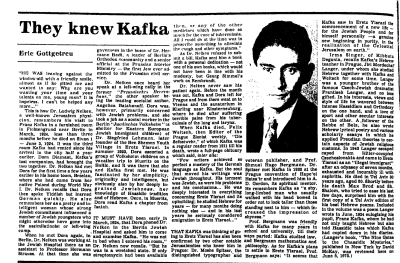

However, Dora ran away a second time, and again travelled to Breslau. This time, her father gave up trying to bring her back. She worked in a children’s home, learned German, and moved in literary and student circles. Her acquaintances included the journalist from Berlin, Dr. Manfred Georg (Manfred George, 1893–1965),[36] who at that time was the chief editor of the “Vossische Zeitung” newspaper in Breslau. Following his expatriation from Germany in 1938, he became editor in chief of the “Aufbau” news-sheet published by the German Jewish Club in New York. The Breslau-born doctor Dr. Ludwig Eleazar Nelken (1898–1985), who studied medicine there at the end of the First World War, and who most recently worked as a doctor in Jerusalem, remembered that Dora, who came from Poland, spoke Yiddish, but learned German very quickly. According to Nelken, the strict devotion of the pretty, intelligent woman to all things Jewish had an influence over a certain number of young Jewish people who had otherwise assimilated or who had joined the left-wing camp (see PDF).[37]

[30] On the early years of Dora Diamant’s life and her family background, see Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 41–50 (German language edition).

[31] See: Będzin, at Świętokrzyski Sztetl – Ośrodek Edukacyjno-Muzealny, http://swietokrzyskisztetl.pl/asp/en_start.asp?typ=14&menu=178&sub=173 (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[32] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 45.

[33] A description of Hebraica in Będzin by Moshe Rozenkar, one of the founders, is included in the volume by Abraham Samuel Stein (Avraham Shemuʼel Shtain, 1912–1960), which is over 400 pages long, and which is written in Hebrew and Yiddish: Pinkes Bendin. A Memorial to the Jewish Community of Bendin (Poland), Tel-Aviv: Hotsẚat Irgun yotsʾe Bendin be-Yiśrẚel, 1959, page 294, https://archive.org/details/nybc313684/page/n6/mode/2up (last accessed on 04.08.2023). The account also contains the earliest photograph of Dora Dymant, taken in around 1916. She can be seen together with the other women and girls in the Hebrew class and their teacher, David Maletz (Fig. 2), page 294.

[34] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 27, 46, 48.

[35] Dora’s own account of her life in the Komintern file in Moscow, quoted from Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 49.

[36] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 49.

[37] Eric Gottgetreu: They knew Kafka, in: “The Jerusalem Post Magazine”, Jerusalem, 14/6/1974, page 16 (see PDF), https://archive.org/details/TheJerusalemPost1974IsraelEnglish/Jun%2014%201974%2C%20The%20Jerusalem%20Post%20Magazine%2C%20%2314%2C%20Israel%20%28en%29/page/n7/mode/2up (last accessed on 4/8/2023). The passages relating to Ludwig Nelken again in German translation as Ludwig Nelken: Ein Arztbesuch bei Kafka, in the collected volume of Hans-Gerd Koch: “Als Kafka mir entgegen kam …” 1995 (see Bibliography), page 186 f.

A new life in Berlin

In 1920, Dora Diamant travelled to Berlin, where she became part of the Jewish community. As she later wrote in her “diaries”, she felt “intoxicated by Germany”.[38] Nelken, who was by now employed as an assistant physician at the Jewish Hospital (Jüdisches Krankenhaus) in Berlin, later remembered that Diamant worked as a child minder in the household of Hermann Badt (1887–1946), a Prussian ministerial counsellor from Breslau.[39] Badt worked for the Interior Ministry, represented the SPD in the Prussian state parliament (Preußischer Landtag) from 1922, and in the pre-war years was actively involved in the Zionist movement. Later, Diamant worked as a dressmaker in an orphanage in Charlottenburg, where she also lived.[40] According to Nelken, she spoke at a “left-wing” rally in the building of the former Prussian upper chamber of parliament (Preußisches Herrenhaus), at which the socialist politician living in Italy, Angelica Balabanova (1869–1965), also gave a speech. However, in Nelken’s account, Diamant was primarily interested in Jewish issues, and took up employment as a social worker in the Jüdisches Volksheim, which took in children of Jewish immigrants from eastern Europe. One of Diamant’s role models in Berlin was the communist Reichstag member and women’s rights campaigner, Clara Zetkin (1857–1933),[41] with whom Balabanova organised women’s congresses.

Diamant learned about the activities of the Volksheim shortly after arriving in Berlin, and offered her services as a kindergarten teacher, or “Fröblerin”. Her approach to teaching was based on the principles of the German educator Friedrich Fröbel (1782–1852), which she had learned during her training in Krakow and which were applied in kindergartens in Austria-Hungary.[42] However, her real interest lay in a project to prepare the children for a move to Palestine: “She passionately believed in the need for a Jewish homeland in Palestine, in Eretz Israel, the Promised Land. In her daydreams, she said she frequently saw herself ‘in the fields of Galilee’, in a kibbutz, working and living side by side with other free Jews, men and women from all countries, cultivating moors and wasteland, planting gardens and creating a safe, just world for her future children and grandchildren”.[43]

The Jüdisches Volksheim (Fig. 3) was founded in 1916 by the Berlin physician and educator Siegfried Lehmann (1892–1958) in Dragonerstrasse 22.[44] It was funded by Max Brod, the religious philosopher Martin Buber (1878–1965), the anarchist writer Gustav Landauer (1870–1919, murdered), the businessman, factory owner and art collector Siegbert Samuel Stern (1864–1935) and the Berlin Rabbi Malwin Warschauer (1871–1955). The aim was to offer a Jewish upbringing, further and general education, sports activities and music lessons to children and adolescents from the impoverished homes in the Scheunenviertel district of Berlin, which were overflowing with Jewish refugees from Galicia and Silesia. Evening activities were also offered for mothers, as were medical and legal advice.[45]

The daily routine in the People’s Home was divided into playtime for the children in the morning, followed by afternoon group activities (“Kameradschaften”) for girls and boys, clubs for young girls and apprentice clubs with male adolescents in the evening. Groups for children and boys were kept busy with Fröbel-inspired tasks such as basket weaving, handicrafts with cardboard and clay, and also Hebrew children’s songs and dance games. Other days were “dedicated to the reading and telling of fairytales, legends and life experiences”. Older boys were taught carpentry, bookbinding and metalworking, while the girls learned sewing and handicrafts, and sang in a choir once a week.[46] According to the account, the Volksheim gave Diamant “a sense of community and family”.[47] She had grown up with the “Hasidic traditions and stories from east Jewish mysticism” and “her language and manner of expression was characterised by the phrases and old Jewish allegories of her grandmothers”. Later, she would enchant Kafka every evening with the “bubbe meises”, the fairytales and folk legends of the old Jewish women.[48]

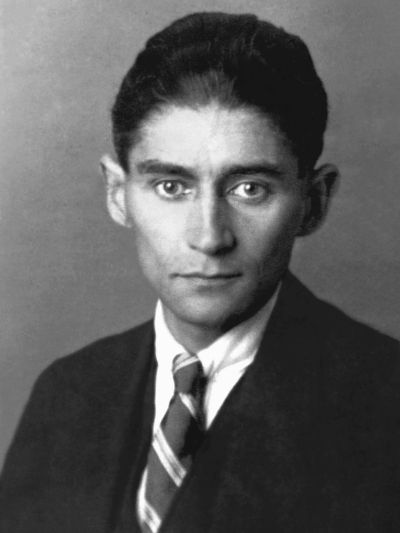

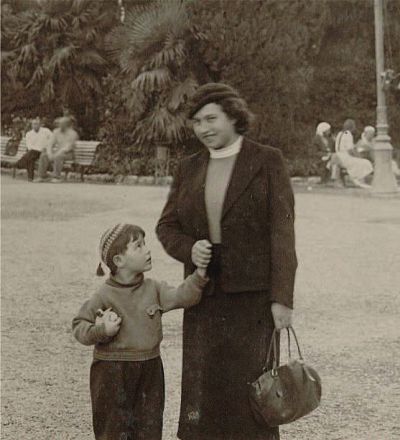

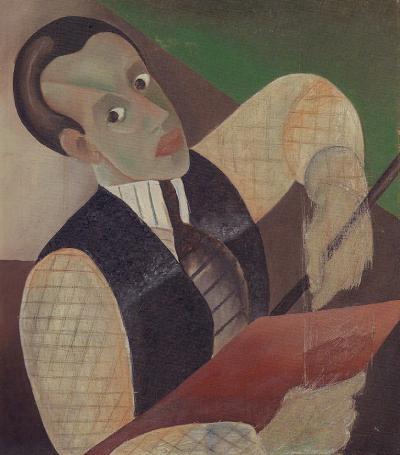

When Kafka (Fig. 4) and Diamant met for the first time in the Jewish holiday home in Müritz on the eve of the Sabbath on 13 July 1923, it soon became clear that for him, the young woman embodied many aspects of Jewish life in which he had been interested for some time. While she had already learned Hebrew in her childhood by listening in while her brothers were taught in the cheder school, for Kafka, learning the language was a painful process that had only begun in 1917, the year in which he was diagnosed with tuberculosis. In the following year, he and Brod learned Hebrew in the literary Prague Circle (Prager Kreis),[49] together with their friend since 1904, the journalist Felix Weltsch (1884–1964). At that time, Diamant was already able to read passages from the Bible in the original. She came from the Będzin theatre group, while in 1910, he had been delighted to discover an eastern Jewish theatre company in the “Café Savoy” in Prague. Through the company, he and Brod had immersed themselves “into what for us was a new world of eastern Jewish people’s strength”, which in turn caused Kafka to study Jewish history and Yiddish literature.[50]

Through Diamant, Kafka finally acquired a personal connection to the Jüdisches Volksheim, the aims and work of which he had heard about from Brod and their mutual long-term acquaintance, Martin Buber. He had urgently advised his previous fiancée, Felice Bauer (1887–1960) to work in the Volksheim as a “path to spiritual liberation”.[51] Following his advice, Bauer then began to organise literature classes for girls at the home. Now, from Müritz, Kafka wrote to his Prague schoolfriend Hugo Bergmann (1883–1975), who by now worked as a librarian at the Hebrew National Library in Jerusalem: “When I look through the trees, I can see the children playing. [...] Eastern Jews, saved from danger in Berlin by western Jews. For half the days and nights, the house, the forest and the beach are full of song. When I am among them, I am not happy, but on the threshold of happiness. [...] Today, I shall celebrate Friday evening with them, I think for the first time in my life.”[52] Bergmann, a pupil of Buber who was also a friend of Weltsch and Brod, had explained the concept of Zionism to Kafka. Now, Kafka and Diamant dreamed of leaving for Palestine together. From that time on, they were inseparable: “Franz helps peel potatoes in the People’s Home in Müritz. The night on the landing stage. On the bench in the Müritz forest”, Diamant noted in her “diary” during the final days of her life.[53]

On 6 August 1923, Kafka left Müritz, spent two days in Berlin, and then, severely ill, embarked on the train journey to Prague. For about a month, Diamant continued to work at the holiday home in Müritz. At first, Kafka continued his study of Hebrew in Prague, and developed an interest in Jewish prayer rituals. During this time, his weight went down to below 60 kilograms. His sister Ottla then took him to a country residence in the village of Schelesen/Želízy, to the north of Melnik/Mělník on the river Elbe, where Kafka had already been three times to convalesce since falling ill with the Spanish flu in 1918. In the interim, Diamant began looking for a place for them both to live in Berlin, as planned. She finally found a large, bright, furnished room with a kitchen and own bathroom, bay windows and a veranda on the third floor of the corner house of what was then Miquelstraße 8, near Steglitz town hall (Fig. 5).[54] While she wrote Kafka “enthusiastic and encouraging” letters up until September, he remained in Schelesen, struggling to recover his health.[55]

[38] Quoted from Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 50.

[39] Gottgetreu 1974 (see note 37).

[40] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 28.

[41] Ibid., page 27.

[42] Ibid., page 26, 49.

[43] Ibid., page 26.

[44] Today Max-Beer-Straße 5. Several websites contain articles about the former Jüdisches Volksheim in Berlin; including: Arbeitskreis Jüdische Wohlfahrt (also on Dora Diamant), https://akjw.hypotheses.org/946, and: Jewish Museum Berlin, https://www.jmberlin.de/berlin-transit/orte/juedischesvolksheim.php (both last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[45] Siegfried Lehmann: Postscript. Über jüdische Erziehung, in: Das Jüdische Volksheim Berlin. First report, May/December 1916, self-published, Berlin 1916, page 17 f., https://archive.org/details/JudischeVolksheimBerlin/page/16/mode/2up (last accessed on 4/8/2023). The five patrons are named on a separate dedication page.

[46] Ibid., page 6–11.

[47] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 25.

[48] Ibid., page 33–35.

[49] Miriam Singer: Hebräischstunden mit Kafka, in the collected volume of Hans-Gerd Koch: “Als Kafka mir entgegen kam …” 1995 (see Bibliography), page 140–143. In 1922, Kafka, by now physically weakened, again began to study Hebrew more intensively. In the words of his Palestine-born Hebrew teacher, Puah Ben-Tovim (1904–1991): “Between 1917 and 1923, Kafka gradually began to become aware of his Jewishness. [...] I also think that he felt so attracted to Dora Diamant largely because she came from an ultra-conservative Hasidic family. He wanted to know everything about the life of the pioneers in Palestine [...] Studying Hebrew offered him the opportunity to forge an at least symbolic connection to Palestine [...] I was already living in Berlin when Kafka wanted to visit me in a summer holiday camp in Eberswalde where I worked [...] Kafka asked me to start teaching him Hebrew again, and I gave him five or six lessons. Then I realised that in fact, this could also be done by Dora, who had a good basic knowledge of the language). (Pouah Menczel: J’Etais Professeur D’Hebreu de Kafka, in: Libération, Paris, 2-3/7/1983, page 19 f.; published again as Puah Menczel-Ben-Tovim: Ich war Kafkas Hebräischlehrerin, in the collected volume of Hans-Gerd Koch: “Als Kafka mir entgegen kam …” 1995 (see Bibliography), page 165–167.

[50] Brod 1962, German language edition, page 135–137. For her part, Dora Diamant noted the following in her records in around 1950 under the title “From Franz’ Quartheften. 3/10/1911. Last lines of entry”: “The first direct encounter with the eastern Jewish world through Löwy’s theatre group. With the performance, ‘Der Meschumed‘ by Lateiner’ having made an impression on him”, there follows a word-for-word quote from Kafka’s diaries [“Quartheften”] dated 8/10/1911: “My wish is to see a great Yiddish play, since the performance may have suffered from the small number of people involved and the imprecise production. Also, the wish to know Yiddish literature, which evidently has the nature of an uninterrupted national fighting position...”; quoted from Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 394.

[51] Franz Kafka to Felice Bauer, 12/9/1916, in: Franz Kafka: Briefe an Felice und andere Korrespondenz aus der Verlobungszeit, Frankfurt/Main 1976, page 696 f.

[52] Franz Kafka to Hugo and Else Bergmann, Müritz, 13/7/1923, in: Franz Kafka: Briefe 1902–1924, Frankfurt/Main 1975, page 436 f.

[53] Dora Diamant: Chronologische Initialien, in: Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 405.

[54] Now Muthesiusstraße 20–22; see Sarah Mondegrin: Kafka in Berlin. Das vergessene Haus, in: “Tagesspiegel”, 2/12/2012, https://www.tagesspiegel.de/kultur/das-vergessene-haus-2246500.html (last accessed on 4/8/2023). The landlady, Clara Hermann, was deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto in 1942, where she died on 19 March 1943. In 2015, a “stumbling stone” (Stolperstein) was set in front of the house at Muthesiusstraße 20 in her memory. https://www.stolpersteine-berlin.de/de/muthesiusstrasse/20/clara-hermann (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[55] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 50–56.

Franz Kafka and Dora Diamant move in together

At last, on 21 September, he seemed to be sufficiently recovered to attempt the journey to Berlin three days later. Even on the way to the station, his father tried to persuade him to change his mind. For his part, Kafka made no mention of Dora’s existence, since his parents had already been incensed by his engagement to Julie Wohryzek (1891–1944, Auschwitz concentration camp), the daughter of a grocer and synagogue sexton. On the two days previously, he had almost backed off from his own “foolhardiness” in moving to Berlin and daring to enter into a new relationship. He had been kept awake during the night by indescribable “fears”. When he arrived in Berlin, the small shared apartment assuaged his fears at first. However, rampant inflation made any kind of normal life almost impossible. In September 1923, a loaf of bread cost 4 million marks. On 2 October, he wrote to Ottla: “... the prices are climbing like the squirrels where you are. Yesterday, they almost made me a bit dizzy, and I find the inner city quite dreadful, for this reason and otherwise. That aside, for the time being, it is peaceful and beautiful here on the outskirts. When I leave the house during these warm evenings, I am met with a scent from the old, lush gardens, which I don’t believe I have ever felt anywhere to this degree of delicateness and intensity...”.[56] Two weeks after his arrival, he told Ottla, Brod and Klopstock that he was considering remaining in Berlin and even spending the winter there.[57] For a long time, he made no mention of “D.”, however, and it was not until 25 October that he wrote to Brod: “The name is Diamant”.[58]

Although Kafka’s pension was paid out in the Czech currency, which was not affected by inflation, his parents only forwarded the money at irregular intervals. Even so, he still hoped that he could make a living as a freelance writer in the future. At first, Diamant had to get used to the hours he spent writing, his silence while he worked and his solitary walks. She enrolled for courses at the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies (Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums) (Fig. 6) in Artilleriestraße in Berlin-Mitte[59], for which she needed to study at home. She also helped out in the orphanage and continued to work as a volunteer in the Jüdisches Volksheim, where she took up a class in rhythmic dance. During their time together when they were not working, she told Kafka about the life of her family in the Hasidic community in Poland, and they made plans together for a future in Palestine. However, his state of health made it unlikely that they would ever be realised. In mid-November, after the rent on their apartment had risen by more than tenfold in two months when converted into Czech crowns, the couple moved into two “beautifully furnished rooms” with central heating and electric lighting[60] on the first floor of a villa inhabited by Frau Dr. Rethberg at Grunewaldstraße 13 (Fig. 7).[61] That same month, Brod came to Berlin with a heavy suitcase full of Kafka’s winter clothes from Prague.[62]

In the interim, Diamant and Kafka had attended several courses at the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies and travelled by tram to the Scheunenviertel district up to three times a week. Diamant studied Jewish laws, the Halacha, while Kafka took lessons in Jewish stories and legends, the Aggada, from the Lwów/Lemberg-born Bible exegete and Semitist Harry Torczyner (Naftali Herz Tur-Sinai, 1886–1973). Ottla brought Kafka’s pension payments from Prague, which could finally be exchanged at the pre-war rate following the introduction of the Rentenmark. For Diamant, Kafka’s sister became a “trusted ally”.[63]

In the winter of 1923, either before or after the short story “A Little Woman” (Eine kleine Frau), which describes and analyses not only the couple’s previous landlady, but also general human behaviour, Kafka wrote “The Burrow” (Der Bau). Only a fragment of the story remains. In the narrative, the protagonist – either a badger or a creature that is a mixture of human and animal – which has just finished digging its underground, labyrinthine abode, becomes paranoid when it hears sounds that steadily increase in volume. The approaching threat, possibly another burrowing animal, causes him to reflect on his own life, at the end of which he is resigned, however, to the nature of his existence and to the impossibility of eliminating the danger. Ultimately, “everything went on unchanged”.[64] Taken in the context of the time at which it was written, the story refers to the “narrowness and heaviness of life in our own, far too expensive, apartment”; the labyrinth is a reference to the Kafka’s deteriorating health and the hopelessness of his situation, together with the threat of returning to his old life in Prague.[65]

Diamant later reported to J.P. Hodin that “The Burrow... was written in a single night. It was winter; he began early in the evening and was finished towards the morning, then he worked on it again. He told me about it, jokingly and in seriousness. It was an autobiographical story, and perhaps it was a premonition of his return to his parents’ house and the end of freedom that generated this sense of panic and fear. He explained to me that I was the ‘citadel plaza’ in this burrow”.[66] In Kafka’s telling of the story, this “central plaza” – possibly Dora – is “well selected for the eventuality of extreme danger, perhaps not of pursuit, but certainly of a siege ... While everything else may be the work more of a concentrated mind than body, this citadel is in all its parts the product of the very hardest manual labour”.[67] Diamant concluded that “He had experienced life as a labyrinth from which he could see no way out”.

It was probably during the Christmas period that Ottla told Kafka’s parents about Dora for the first time. They supported the couple by sending them food parcels. A heavy package arrived from his sisters with household utensils. Before Christmas, Kafka became ill. Every evening during the first two weeks of January, he again suffered from fever, shivering, intestinal problems, and a cough that lasted until the morning. Diamant called a doctor from the Jüdisches Krankenhaus, whose bill, even after she had haggled him down to half the original price, made it clear to Kafka that he could not afford to be admitted to the hospital as an inpatient. The never-ending price increases in the Rentenmark meant that the couple were forced to give notice on their apartment and move out by 1 February 1924. They feared that they would have to leave Berlin entirely. On that date, however, they moved into a one-room apartment in the villa of the widow of the deceased writer and literary critic, Carl Hermann Busse (1872–1918) in Heidestraße 25-26 in Zehlendorf.[68] By this time, Diamant was attending Kafka’s evening appointments, as he himself had been unable to leave the house at night for several months. They included a lecture evening given by the reciter and actor Ludwig Hardt, an acquaintance of Kafka, in the Meistersaal hall on Potsdamer Platz. Diamant rediscovered her own talent for the theatre, and was further encouraged by Kafka and the Prague actress Midia Pines (Midia Kraus, 1893–1965), a friend of Kafka’s.

It was evidently in the Zehlendorf apartment that Diamant burned several of Kafka’s works. She told Hodin that he was obsessed with the idea; to a certain extent, it was a form of stubborn protest: “He wanted to burn everything that he had written in order to free his soul from these ‘ghosts’. I respected his wish, and when he lay ill, I burnt things of his before his eyes. What he really wanted to write was to come afterwards, only after he had gained his ‘liberty’.”[69]

[56] Franz Kafka to Ottla Kafka, Berlin-Steglitz 2/10/1923, in: Franz Kafka: Briefe an Ottla und die Familie, Frankfurt/Main 2011, page 134 f., https://homepage.univie.ac.at/werner.haas/1923/ok23-106.htm (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[57] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 59-74.

[58] Franz Kafka to Max Brod, arrival postmark Praha-Hrad, 25/10/1923, in: Max Brod, Franz Kafka – eine Freundschaft 1989 (see note 1), page 434 f., https://homepage.univie.ac.at/werner.haas/1923/bk23-012.htm (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[59] Now Tucholskystraße 9, known as the Leo-Baeck-Haus and headquarters of the Central Council of Jews in Germany (Zentralrat der Juden in Deutschland).

[60] Franz Kafka to his parents, Berlin-Steglitz, beginning of November 1923, https://homepage.univie.ac.at/werner.haas/1923/el23-003.htm (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[61] See Karen Noetzel: Vor 90 Jahren genoss Franz Kafka das Vorstadtidyll, in: “Berliner Woche”, 6/1/2014, https://www.berliner-woche.de/steglitz/c-sonstiges/vor-90-jahren-genoss-franz-kafka-das-vorstadtidyll_a43304 (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[62] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 75–92.

[63] Ibid., page 93–105.

[64] Franz Kafka: The Burrow, in: Franz Kafka. The Burrow, London 2017, page 183–220.

[65] Florian Kraiczi: Der Einfluss der Frauen auf Kafkas Werk. Eine Einführung (Schriften aus der Fakultät Geistes- und Kulturwissenschaften, 1), Bamberg: University of Bamberg Press, 2008, page 119–124, https://fis.uni-bamberg.de/bitstream/uniba/118/1/Dokument_1.pdf (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[66] Hodin 1948 (see Bibliography), page 38; quoted from Dora Diamant: Mein Leben 1995 (see Bibliography), page 179.

[67] Kafka: The Burrow (see note 64), page 186.

[68] Today Busseallee 9. The house has been rebuilt and bears a memorial plaque to Franz Kafka. The widow Paula Busse (*1876) was liberated from the Theresienstadt ghetto in 1945.

[69] Hodin 1948 (see Bibliography), page 39.

“If only there had been a medicine available” – Kafka’s illness and death

Kafka’s health continued to deteriorate. This was confirmed by his uncle, the country physician Dr. Siegfried Löwy (1867–1942 suicide prior to deportation), who came to Berlin for a few days and who advised him to have himself admitted to a sanatorium. At the beginning of March, Diamant raised the alarm with Dr Nelken from the Jüdisches Krankenhaus. Although he did not find Kafka in bed, the patient was in a terrible state. As Nelken remembered later: “If only Streptomycin or another medication against tuberculosis had been available then. All I could do was to prescribe something to alleviate his cough and other symptoms”.[70] Diamant had abandoned her classes at the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies and now dedicated herself fully to caring for Kafka. She earned a small amount of money as a dressmaker. Through his connections, Löwy organised a place for Kafka in a sanatorium in Austria without having to wait. Klopstock travelled to Berlin to offer his support. On 17 March, Kafka travelled to Prague, accompanied by Brod. Diamant remained in Berlin.[71]

Kafka spent three weeks in his parents’ apartment, bedridden and emaciated and weighing just 49 kilograms. He was visited there by Klopstock. There were already signs that the tuberculosis was spreading to his larynx. After Löwy had taken care of Kafka’s admission to the Sanatorium Wienerwald, Diamant travelled to Vienna and visited him on 8 April. “D. is with me, that is very good, she is living in a farmhouse next to the sanatorium”, Kafka wrote to his parents.[72] Just three days later, after being diagnosed with tuberculosis of the larynx, he was moved to Professor Markus Hajek (1861–1941) at the Laryngologische Universitätsklinik in the General Hospital (Allgemeines Krankenhaus) in Vienna, where Kafka was accommodated in a large, multi-bed room filled with dying patients. However, when Felix Weltsch found out about the private lung clinic run by Dr. Hugo Hoffmann in Kierling (Fig. 8), 15 kilometres to the north-west of Vienna, which boasted single rooms and private balconies for less money, Kafka and Diamant insisted that he be moved there just eight days later.[73]

Diamant was also able to live there. She took on the correspondence with Kafka’s parents and sisters, who made telephone calls to the sanatorium every day. At the beginning of May, the Viennese lung specialist, Dr. Oskar Beck, whom Diamant had called on for a consultation, diagnosed a non-treatable condition of the lung and larynx, and advised Diamant to transport Kafka back to his family in Prague. In the interim, Klopstock had also moved into the sanatorium to help care for the patient. The letter from Dora’s father in Poland, whom she had not seen for four years, in which he denied his permission for she and Kafka to marry, arrived on 12 May. On the same date, Brod travelled from Prague to Vienna to visit his ill friend for a day. Brod, Diamant and Klopstock agreed that Kafka should remain in Kierling, since a return to Prague would cause him to lose all hope.[74]

On 25 November 1953, the Prague-born publicist Willy Haas wrote an article about “Franz Kafka’s death” on 3 June 1924 in the Berlin newspaper “Der Tagesspiegel” after a nurse, Anna, who had cared for Kafka until the end in the sanatorium in Kierling, had written him a letter. “Kafka took various precautions in the event of his death. We already know about the agreement with Dr. Klopstock that he should bring about a quick end with a syringe if all hope was lost. It appears that Kafka, in an hour of weakness, granted his life companion Dora permission to die with him. None of these arrangements were followed through. However, the loyal Klopstock did adhere to a third, secret agreement that in the final hour, he was to send Dora away on some pretext so that she would not witness the death struggle. Klopstock did so, and asked Dora to take a letter to the post office. However, in the final minutes, Kafka missed Dora. ‘I sent the maid after her’, the nurse writes, ‘since the post office was close by’. Dora came back out of breath, carrying flowers that she had presumably just bought. Kafka appeared to be fully unconscious. Dora held the flowers in front of his face. ‘Franz, look at the beautiful flowers! Smell them!’, she whispered. ‘Then the dying man sat up and smelled the flowers. [...] He had such wonderfully bright eyes, and his smile said so much, and his hands and eyes were so expressive, now that he could no longer speak’”.[75]

At the request of Kafka’s father, Löwy came to Kierling to take care of the body. According to the nurse’s account, he pushed Diamant and Klopstock to one side “in a rather rough manner” and dealt with the formalities with “cool, indifferent professionalism”. However, an order came via telegram from Kafka’s father on 4 June: “Dora decides”; in other words, she should decide what should happen with the body.[76] Kafka’s body was then taken to Prague by train. Obituaries by Brod, Weltsch, and the writer Oskar Baum (1883–1941) appeared in the German-language Prague newspapers, and Milena Jesenská also wrote an obituary on 6 June in the Czech daily newspaper Národní Listy. On 11 June, Kafka was buried in the New Jewish Cemetery in Prague-Žižkov, with his family and closest friends in attendance. The poet and essayist Johannes Urzidil (1896–1970), who was the press attaché at the German Embassy in Prague, recalled in an essay: “I walked in the wake which followed Kafka’s coffin from the ceremonial hall to the open grave; behind his family and his pale companion, who was supported by Max Brod”.[77] He wrote that Dora broke down at the open grave with anguished, piercing screams.[78]

On the following day, with Diamant present, a memorial ceremony attended by 500 guests was held in the German-language Kleine Bühne theatre in Prague, with speeches and readings from Kafka’s works. During the days and weeks that followed, Diamant remained in Kafka’s parents’ apartment, while Brod began to sort through his literary estate. While doing so, he discovered written instructions from Kafka, addressed to Brod, requesting that “everything written and drawn” that he found in his estate “should be burned completely, without being read”.[79] This would later bring Brod into conflict, not only with his own conscience, but also with Diamant, who later wrote to him that: “Knowledge about Franz should be kept from the whole world. It is none of the world’s concern, because – well, because the world doesn’t understand him.[80]

[70] Gottgetreu 1974 (see note 37).

[71] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 107–122.

[72] Postcard from Franz Kafka to Hermann Kafka, Ortmann 9/4/1924, https://homepage.univie.ac.at/werner.haas/1924/el24-021.htm (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[73] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 123–135.

[74] Ibid., page 137–157.

[75] Willy Haas: Franz Kafkas Tod, in: “Der Tagesspiegel”, Volume 9, No. 2497 dated 15/11/1953, supplement, page 1; reprinted as Willy Haas: Die letzten Tage, in the collected volume of Hans-Gerd Koch: “Als Kafka mir entgegen kam …” 1995 (see Bibliography), page 193–195.

[76] Telegram from Hermann Kafka, archive of the Kafka Research Centre (Kafka-Forschungsstelle) at Wuppertal University (Bergische Universität/Gesamthochschule Wuppertal); quoted from Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 161.

[77] Johannes Urzidil: 11 June 1924, in: idem, Da geht Kafka. Essays, Zürich/Stuttgart: Artemis, 1965, page 78.

[78] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 159–166.

[79] Max Brod: postscript to the first edition, in: Franz Kafka. Die Romane. Amerika. Der Prozeß. Das Schloß, Frankfurt/Main: S. Fischer, 1965, page 472.

[80] Dora Diamant to Max Brod, Berlin 2/5/1930, in Max Brod: Der Prager Kreis, Stuttgart et al.: Kohlhammer, 1966, page 113.

The stage boards that mean the world

Two months later, in August 1924, Diamant (Fig. 9) suddenly packed her bags and left. Urzidil had organised a residence permit for her for Germany, with which she was able to travel to Berlin. Kafka’s family had given her a small amount of money to take with her. At first, the German capital, as she wrote to Elli, felt “like the cemetery of my life, where I came to visit the graves”. A few days later, friends found her a room in a student hostel. She had hopes that she would be able to begin training as an actress.[81] In October, she reported to Ottla in a letter that she was about to take the entrance exam to the state acting school. She wrote that she had been helped in preparing for the exam by an actress who was an acquaintance of the theatre director and manager, Max Reinhardt (1873–1943). By January 1925, she had found greater stability in her life. Although she had failed the entrance exam to the acting school, she had moved into a new apartment, had found work, attended courses and did gymnastics. She also developed a friendship with the Polish-Yiddish poet Avrom Nokhem Stencl (Sztencl, Stenzel, Abraham Nahum Stencl, Avrom-Nokhem Shtentsl, 1897–1983), who came from Czeladź, a neighbouring town to the west of Będzin.[82]

Stencl, who had fled conscription to the Polish army in 1918, had arrived in Berlin via the Netherlands in 1921, the same year as Diamant. He remained in Berlin until his emigration to Britain in 1936. During this time, he published ten volumes of Yiddish poetry. Often homeless, with his pockets full of poems, he gathered other Polish literati from his home region around him and sought contact with non-Jewish literary expressionists. From 1922 onwards, he collaborated with the poet Else Lasker-Schüler (1869–1945) and spent many sociable hours in the Romanisches Café on Kurfürstendamm, where Jewish exiles, intellectuals and activists from Poland, Ukraine and Russia mingled with artists, actors, journalists and chess players. It is likely that he fell in love with Diamant,[83] although he was in a committed relationship with the artist Elisabeth Wöhler, who worked at the Free Secular School (Freie Weltliche Schule) in Reinickendorf, where he also taught. In 1942, Diamant met him again in Whitechapel, London, where he established himself as the “Poet of Whitechapel”[84], declaring the area his British shtetl.[85] (Fig. 10) Like Diamant, he was committed to the dissemination of the Yiddish language, and published “Loshn un lebn” (“Language and Life”), for which Diamant wrote articles from 1945 to 1949.

In the spring of 1925, Diamant (Fig. 11) fell seriously ill. When she ran out of money, she went to stay with relatives in Brzeziny, the birthplace of her mother. At the beginning of 1926, she returned to Berlin and moved into a room at the orphanage in Charlottenburg. During that year, Brod published Kafka’s novel “The Castle” (Das Schloss) via the Kurt Wolff Verlag publishing house in Munich. From that time on, Diamant, to whom he sent a free copy, started collecting any writings and novels that were published, and anything else that was written about Kafka. She found new lodgings in an artist’s studio in the Hansaviertel district, not far from the Tiergarten, earned money from sewing, and took up acting classes again. Klopstock, who was now living in Kiel, visited her in Berlin during the Whitsun holiday. Brod and Haas, who had edited the journal “Die literarische Welt” in Berlin since 1925, paid her royalties received from Kafka’s novels and stories. It was thanks to these that Diamant, whose health had still not fully recovered, was able to afford a two-month holiday on the Baltic coast.[86]

In November 1926, after applying for acting training courses and theatre roles across Germany, she was accepted at the Academy for Dramatic Art (Hochschule für Bühnenkunst), which was affiliated with the Schauspielhaus Düsseldorf theatre (Fig. 12). The course curriculum comprised of reading plays, elocution, role study, theatre history, fencing and gymnastics. During the evening, the students took part in rehearsals in the Schauspielhaus and played minor roles in the performances. The most famous student at the academy was the actor Gustav Gründgens (1899–1963), who had studied there in 1919/20. The Schauspielhaus was run by the actress Louise Dumont (1862–1932) and her husband Gustav Lindemann (1872–1960), who had founded it as a private theatre in 1904. Their main focus was ensemble work, and they made the theatre famous as a “reform stage”. A qualification from the academy which they also founded was considered a guarantee of success for a future career. From November 1926 to May 1928, Diamant (Fig. 13) attended classes given by Dumont, who was well known throughout Europe for her performance of Hedda Gabler and other Henrik Ibsen characters, as well as by the actor and director Hermann Greid (1893–1975) and the actor and later theatre manager, Franz Everth (1880–1965).[87]

In early 1927, it is likely that Brod met Diamant when he came to Düsseldorf for the première of his play “The Opuntia – Comedy of a Prominent Individual” (Die Opuntie – Komödie eines Prominenten, 1926) in the small house (Kleines Haus) of the rival Düsseldorf Stadttheater, where he held a series of lectures from February to March. During that same year, he published Kafka’s third novel, “Amerika”, and was again able to negotiate royalties for Diamant.

We can assume that it was in Düsseldorf in 1927 that Diamant also met the poet, playwright and journalist Berta Lask (1878–1976), her future mother-in-law, for the first time. Lask, who was born in Wadowitz/Wadowice in Galicia, had become radicalised following her experiences of the First World War in which she lost both her brothers, the Russian October Revolution, the November Revolution of 1918 in Germany, and not least the poverty in Berlin during the post-war years. After early literary attempts, she published poems, stories and plays which were closely linked to the Expressionism and literary activism surrounding Kurt Hiller (1885–1972). In 1923, she joined the KPD, the Communist Party of Germany. In 1927, she was due to produce her play “Leuna 21”, about the workers’ revolt during the “March Action” of 1921, at the Düsseldorf Schauspielhaus theatre. Shortly before, the premiere of the play had been banned in Berlin, and its first night in Düsseldorf was also prohibited by the authorities. Lask was accused of high treason, and her works were removed from the bookshops.

At this time, Diamant, as she would later recount for the record in Moscow, was also in contact with a “Sternberg Group”. This was a political group oriented around the theories of the sociologist and Marxist theoretician Fritz Sternberg (1895–1963), who had been influenced by the theories of Martin Buber, a Jew from Breslau. It was through this group that Diamant “was introduced to the basics of Marxism”. She was “enlightened” about communism by the actor Wolfgang Langhoff (1901–1966), a fellow actor at the Schauspielhaus and a communist, KPD member and later member of the Association of Revolutionary Fine Artists (Assoziation revolutionärer bildender Künstler) or ASSO.[88]

From October 1927 onwards, Diamant acted at the Schauspielhaus in performances of “The Prince of Homburg” (Der Prinz von Homburg) and “The Broken Jug” (Der zerbrochene Krug) by Heinrich von Kleist, and from January 1928 she played a “Moorish girl” in Henry Ibsen’s play “Peer Gynt”. Diamant’s teachers, Greid and Everth, praised her “strong, unique talent”.[89] While on arrival in Düsseldorf she had officially registered as “Dwora Dimant”, in January 1928, she altered the spelling of her surname to “Dymant”. However, a fellow actress, Luise Rainer (1910-2014), who would quickly become famous, knew her simply as “Doris”: “She was a dark person, always dressed in black, as though she was in mourning. I had never read Kafka, but she talked to me constantly about him. [...] She seemed to me to be entirely suffused by him. [...] Doris was a real character. She was someone”.[90] As Diamant recounted to Brod, she completed her training in May 1928 with a lecture evening at which she read from Kafka’s novel “Amerika”. She again applied for work at numerous German theatres – among them theatres in Berlin and the Hamburgische Schauspielbühne theatre run by Madeleine Lüders (1892–1966). This time, she was able to show letters of recommendation from the academy.[91]