A forbidden love – Princess Elisa Radziwiłł and Wilhelm of Prussia

In the middle of June 1820, on the occasion of the Prince’s birthday, the Radziwiłł family came to stay for a few days at Schloss Freienwalde near Berlin. The castle had been specially built in 1798 for Queen Friederike Luise, but had stood empty since her death. Sometime later Wilhelm (ill. 1) also arrived there with his two brothers. Here Wilhelm and Elisa experienced the happiest days of their lives and declared their love for one other. Back in Berlin, Wilhelm was seen coming out of the Radziwiłł Palace in Wilhelmstraße almost every day. Disturbed by the public rumours that his 24-year old son was making advances to the 16-year old daughter of Prince Radziwiłł, the King consulted his advisers.

His brother-in-law, Grand Duke Georg von Mecklenburg-Strelitz, a brother of Queen Luise, thought that Elisa would make an attractive and excellent partner for his nephew because Prince Radziwiłł was one of the former ruling princes in the Empire. In 1515, the Polish/Lithuanian aristocratic family, Radziwiłł was raised to the status of Princes of the Holy Roman Empire by Kaiser Maximilian. Nonetheless the family had no territory immediately adjacent to the Empire because their huge amount of property lay outside its boundaries. Hence they had no seat in the Reichstag and as a result were not members of the Reich Council of Princes. There had been marriages between the Princes of Brandenburg and the Radziwiłłs for the previous 200 years. Thus Ludwig, the third son of Grand Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Brandenburg, had married Princess Luise Charlotte Radziwiłł in Königsberg in 1681, she being the sole daughter and heiress to Boguslaw Radziwiłł, the vice-regent of Prussia. That said, at that time the Princes of Brandenburg had no regal office and were only awarded such status in 1701 when Friedrich III of Brandenburg crowned himself King of Prussia.

According to the law of the Hohenzollern house passed by Friedrich the Great, princes who were eligible to marry could only do so to daughters of ruling princely houses or sovereigns who were recognised by the Reich. Privy Councillor Friedrich von Raumer who was responsible for dynastic questions under King Friedrich Wilhelm III (ill. 2) drew up a report in which he pointed out that the marriage of Elisa’s mother, Luise Friederike of Prussia, a daughter of Friedrich the Great’s youngest brother, to Prince Anton Radziwiłł was not in accordance with the law. The King’s closest adviser, Reich Prince Wilhelm zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Hohenstein, composed a list of daughters of twenty-nine reigning European royal houses who were still waiting to be married; thus Wilhelm’s marriage to a Polish woman was entirely unnecessary.

The children of the Radziwiłłs and the Prussian king and queen had spent a carefree childhood together during their three year exile in Königsberg. Whereas the parents feared for the continuing existence of Prussia after Napoleon’s victory at Jena and Auerstedt in October 1806, according to Dagmar von Gersdorff in a book she published in 2013 entitled “Auf der ganzen Welt nur sie“ (No One but Her in the Whole World), it was a time of great freedom for the children: “They spent the summer on the Amber Coast of the Baltic Sea, the winter tobogganing together and there were places to play in front of the Steindammer Tor [...] and in the old castle [...] Elisa could not only play with her siblings Wilhelm, Ferdinand and Luise, but also with Prince Wilhelm, his brother, the Crown Prince, who was two years older than he was, and his favourite sister Charlotte. When the weather was good they drove to the Dönhoffs in the country or to the large park owned by the Lehndorffs […] Here the children came into contact with people whom they would otherwise scarcely have met, the witty Humboldt gentlemen, the surly Freiherr vom Stein and the crooked Lord von Staegemann, even the poet Archim von Arnim, who worked for a newspaper and had a beard […] Prince Wilhelm found a friend for life in the oldest Radziwiłł son, who was also called Wilhelm and born in the same year and month as he was.” (p. 11 ff.).

In 1809 the royal family and the Radziwiłłs were finally able to return to Berlin after the King had agreed to Napoleon’s reparation claims. One year later Queen Luise (ill. 3) died at the age of 34. Princess Radziwiłł (ill. 4), the daughter of Prince Ferdinand and a cousin of the King, became a substitute mother for the 12-year-old Wilhelm. When the province of Poznan fell to Prussia in 1815 after a decision made at the Congress of Vienna – it was renamed the Grand Duchy of Prussia – the King appointed Prince Anton Radziwiłł (ill. 5), to the post of vice regent of the new Grand Duchy, and to the rank of Lieutenant General: and later he awarded him membership of the Prussian State Council. In 1817 the Radziwiłł family returned to Berlin to take up abode in the palace in Wilhelmstraße. They also had a residence in Poznan, and divided their time between residing in both places for long periods. By now Wilhelm, who was 20 years old, was not content to simply note their return in his diary. He began to meet up with the 24-year-old Elisa in the the palace in Unter den Linden where Wilhelm’s sisters lived, and the two regularly met up at parties and receptions in the carnival season, alongside trips to the country together. From now on it was quite clear for all to see that Wilhelm had fallen in love. A humorous ditty written by the Princesses using the initials of Elisa: “Eternal/Love/I/Such/Amenity” helped her to her nickname Ewig, (Eternal). She went on to sign her letters thus. In January 1818 Wilhelm met up with Elisa in Poznan on his return from St. Petersburg, where his sister Charlotte had married the brother of the Russian Czar Nicholas. “Elisa has really grown up and become somewhat stronger, and more to the point charming“, noted Wilhelm.

The Radziwiłłs returned to Berlin once more for the winter season. The Prince’s “salon”, a regular meeting place for high society, was one of the most highly regarded salons in Berlin. Indeed it was one of the first salons where aristocrats and the middle class mixed together. This was where musicians performed their own works and aristocrats exchanged ideas and opinions with scholars, poets and writers. The Princess placed great value on her children taking part in adult life. Prince Anton Radziwiłł was widely regarded as a talented host and Grandseigneur who, according to Countess Elise von Bernstorff on the period between 1789 and 1835, was the personification of “German ingenuousness and Polish grace“, invited original personalities, Polish relations and friends, and was himself an outstanding composer. Dagmar von Gersdorff writes that, on one occasion when Goethe’s son August was invited, scenes from Goethe’s “Faust“ were presented for which Prince Radziwiłł had written compositions for soloists, choir and orchestra. The settings were designed by the architect, Karl Friedrich Schinkel. All the royal family turned up for the performance, including Prince Wilhelm. The guests also included Freiherr vom und zum Stein, General Gneisenau, Graf Brühl the director of the Berlin Opera, Bettina Brentano and many others.

In January and February 1820 Wilhelm began to visit the Radziwiłłs more frequently. In March the court chaplain and dean of the cathedral confirmed Elisa and her cousin Blanche von Waldenbruchbyx in the chapel of the royal castle, which the King had put at their disposal. This made Elisa eligible for marriage. Countess Bernstorff suspected that the King wanted to use the confirmation to be able to enable the young lady to become his daughter-in-law. It is possible that Wilhelm also thought along the same lines because he was inspired to declare his love for Elisa at Schloss Freienwalde in June 1820. Initially Wilhelm had no knowledge that reports and dossiers had been drawn up opposing any marriage bond with the Radziwiłłs. Nonetheless a number of people continue to work against him in the background. His sister Charlotte unexpectedly advised him to marry Princess Marie von Hessen. His adjutant Oldwig von Natzmer had a serious talk with him that resulted in his admitting it would be impossible to make any closer bond with Elisa without the King’s assent. The upshot was that when he finally saw Elisa when she was on holiday at Schloss Fürstenstein in Silesia his behaviour was withdrawn and frosty. This did not stop him from breaking into tears before Princess Radziwiłł when she took leave of him.

In January 1821 another theatre performance took place in honour of Princess Charlotte – now married and known as the Grand Princess Alexandra Feodorowna – in front of 3,000 guests in the White Hall of the Royal Castle. Here Elisa performed the role of the Goddess Peri in the oriental play “Lalla Rookh” by Thomas Moore. The painter Wilhelm Hensel was not only responsible for the sets and costumes but also painted Elisa in her role (ill. 6). Schinkel, Graf Brühl and the opera director Gaspare Spontini were also involved, the latter as a composer. Indeed Wilhelm, Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, and the Princes Wladislaw and Boguslaw Radziwiłł also had roles in the play. Elisa’s embodiment of “heavenly desire” struck a note with the romantic expectations of the audience and Wilhelm noted in his diary: “Magical, idealistic, an ethereal touch hung over the whole. Unforgettable!!! – E! – semper!” (i.e. “Elisa! For ever!”). By the second performance in February, at the latest, the former Police Minister Prince Sayn-Wittgenstein-Hohenstein, who was responsible for keeping tracks on the national and liberal movements in Prussia, had begun to see something more earthly in this “heavenly” romance. The upshot was that he demanded more information about the Polish family, Radziwiłł. Raumer drew up a second dossier in which he degraded the princely family to the status of minor Polish aristocrats. At the same time Elisa and Wilhelm were seen together at the silver wedding of the Radziwiłłs.

When Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm fell in love with a Catholic Princess from Bavaria – something which he should never have done because she was of the wrong religious denomination – the King decided to review Wilhelm’s marriage intentions once more. Raumer drew up two further reports which maintained that a marriage with Elisa was utterly out of the question. Police President Karl Albert von Kamptz, the head of the body responsible for repressing any liberal currents in society, wrote yet another dossier entitled “A Memorandum on the Legally Inappropriate Status of the Marriage of a Royal Prince of Prussia to Princess Radziwill”, in which he argued that Luise of Prussia who had become Princess Radziwiłł on her marriage, should have renounced any claim to the throne, including any claims from her descendants who of course included Elisa. When Wilhelm’s military adviser, Johann Georg von Brause, showed Raumer’s report to the Prince he was utterly flabbergasted. Wilhelm had never imagined that the Radziwiłłs would be out of the question because of their social status. He suspected that the real reason for the King’s rejection was a result of the disloyal attitude of some members of the Radziwiłł family towards Prussia. Amongst others, Michael Radziwiłł, the brother of Elisa’s father, had fought under Poniatowski and Kościuszko during the Polish uprising, and was subsequently a member of Napoleon’s army.

Wilhelm was told that if we refused to change his intentions the King would hand the matter over to a committee to examine the marriage of the Radziwiłł couple even more closely. People secretly accused Princess Radziwiłł of wanting to turn Elisa into a Prussian princess by marrying her off to Wilhelm. Pressure was put on Grand Duke Georg von Mecklenburg-Strelitz to have a serious word with Wilhelm because, if his brother Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm were to die without an heir, Wilhelm would then succeed to the throne. Thus, for reasons of state, he should renounce any thoughts of marrying the Polish princess. In February 1822 the King himself warned Wilhelm to put his private desires aside on the grounds of Hohenzollern family law, upon which Wilhelm promptly gave up any resistance. “It’s finished!! The precious, loving angelic being is lost to me!”, he noted. Nonetheless Wilhelm and Elisa continue to meet up at balls and on secret dates where they swore to remain friends forever.

Without more ado Wilhelm set off for the Rhineland and the Netherlands in order to flee from his problems. By this time the whole of Berlin had learnt of the Prince’s departure in the newspapers and was following the course of the drama. Meanwhile Prince Oskar of Sweden, who saw no problem in the difference in social status, presented himself as a candidate for Elisa’s hand. Wilhelm spent his 25th birthday, the day on which he had wanted to marry Elisa, in Holland. Elisa was only permitted to write a few harmless words to him, and when Wilhelm wanted to send her a message he wrote it to her mother. His sister Charlotte sent him a small portrait of Elisa as a present from Russia, which he was supposed to have kept on his desk until his death in 1888.

Back in Berlin, following a cool and impersonal meeting with the King, Wilhelm’s resistance flared up once more and he commissioned a counter-study from two legal experts. This was followed by meetings between Elisa and Wilhelm in the theatre, receptions at the Radziwiłł’s house and long conversations in the palace garden on Wilhelmstraße, the content of which the Prince wrote down in the form of a dialogue. “No one else in the world but her!”, he declared. She was the “joy” of his life. Needless to say, the study he had commissioned came out in favour of him and was promptly rejected by the ministers and the Director of Police, Kamptz. On 28th July 1822 the whole Radziwiłł family set off for Silesia and Ruhberg Castle near Schmiedeberg in the Hirschberg valley. Prussian aristocrats, many of whom were friends of the Radziwiłłs, were well-known for their love of this part of the countryside surrounded by hills at the foot of the Sudeten mountains. They had thus erected more than thirty castles, mansions and parks in the Hirschberg valley during the 19th century. Ruhberg castle, which was surrounded by an extensive landscaped park, had been partly designed by the architect Carl Gotthard Langhans, the man responsible for the Brandenburg Gate. Prince Radziwiłł initially rented the summer residence for five months, but in the end the family did not return to Berlin for the next eight years.

Meanwhile Privy Councillor Raumer had presented three further dossiers which described a bond between the two lovers as a “mismarriage” that would undermine the hierarchical structure of the house of Hohenzollern. The Prussian Foreign Minister, Christian Günther Graf von Bernstorff, who was asked to make a judgement on the case, did not feel in a position to assess the equality of birth since the Radziwiłłs were a part of the Polish and not the German aristocracy. As a result he suggested that the King make such a pronouncement. Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, who dearly wanted his brother to lead a happy life, vehemently condemned both the dossier and the intrigues plotted by the “court toadies”. Indeed he had a violent argument with his uncle, Grand Duke Georg, who had also commissioned other dossiers with almost identical results. Whilst Wilhelm was with his father and brothers at a congress of monarchs in Verona, Elisa celebrated her 19th birthday. Wilhelm wrote to her parents: “Elisa is indispensable for the happiness in my life”.

The Radziwiłł family decided not to return to Berlin in order to spare Elisa from any further discussions. By now they interpreted the King’s refusal to agree to the marriage as a monstrous insult, particularly because Princess Luise was related to the King. It was not only the family, but also Wilhelm, who suspected that the decision had been made for political reasons. For Prince Radziwiłł had pleaded for the restoration of the Polish nation, possibly under the leadership of Prussia, not only at the Congress of Vienna but also to the King in person. His opinion was shared by the Reich Freiherr Heinrich vom und zum Stein, a friend of the Prince, and also by Elisa’s best friend Luise von Kleist, whose fiancé was one of the most rebellious of the Polish students. In May 1823 the family moved into the vice-regent’s palace in Poznan, where Elisa began to create a circle of Polish friends and turned her interests towards the culture and history of Poland.

Whilst Wilhelm and Elisa exchanged brief jottings between Berlin and Poznan, alongside pressed flowers and leaves, and pieces of jewellery and locks of hair, the Crown Prince who was furious with Raumer for his arrogance, presented his own research into the history of the Hohenzollerns, and wrote a written statement in which he mocked the dossier drawn up by Prince Wittgenstein, and told the King to make up his mind once and for all. The King had already relented on two occasions. First he had allowed the Crown Prince to marry the Catholic Princess Elisabeth of Bavaria, and then he had allowed Wilhelm to visit his sister in St Petersburg – and travel via Poznan! Wilhelm took his revenge with an affront to the King. He had discovered that the King’s new daughter-in-law, Elizabeth, was directly descended from Prince Boguslaw Radziwiłł via the Elector Karl Philipp of the Palatinate. Thereupon Wittgenstein presented his twenty second dossier on a future “mismarriage” with a Princess Radziwiłł, on the grounds that she did not come from a royal dynasty.

Pressure on the King grew. The Crown Prince complained to his uncle Georg about the coldness and heartlessness of the monarch. Then Wilhelm wrote a letter in which he asked the King for a decision and pleaded with him not to set up a commission whose report would put the Radziwiłł family in an extremely awkward position. However he did say that he would agree to any decision made by the King. Princess Radziwiłł also wrote a letter in which she complained of the public humiliation the family had been forced to suffer, and begged to be spared any further surely mortifying recommendations made by a commission. Nonetheless the King appointed a commission, consisting of Wittgenstein, General Duke Gneisenau and several ministers, whose report in June 1824, was condemned by Wilhelm as spineless. The King had called a family meeting in the Hirschberg valley, whereupon the Radziwiłł family at Ruhberg Castle awaited the whole royal family including Charlotte from St. Petersburg and the new Crown Princess Elisabeth. It is possible that the King wanted to (in the words of Dagmar von Gersdorff), “take a personal look at” his son’s “constant love”. The meeting was friendly and warm-hearted. Elisa’s beauty and grace made a lasting impression on King Friedrich Wilhelm III, so that on his return to Berlin he did everything in his power to enable her to marry Wilhelm despite all the opposition.

The legally approved wedding should now make it possible for Elisa to be adopted by a ruling royal house. Kamptz and Raumer presented further dossiers in which they now referred to historic adoptions in Europe. The King asked the Russians Czar to help him out by adopting Elisa, but the latter refused on the grounds that legally unapproved weddings in the Czar’s family had not been resolved this manner. An adoption into the house of Habsburg was out of the question on political grounds. The Radziwiłł family regarded the whole idea of an adoption as an additional humiliation because, according to Dagmar von Gersdorff, this would be written proof of the lower status of an “age-old Polish/Lithuanian princely dynasty” in comparison to the “more recent Prussian aristocracy”. Finally the only person who could come into question for an adoption was Prince August of Prussia, the youngest brother of Princess Luise, the Infantry General and the wealthiest landowner in Prussia. The Radziwiłłs only agreed to this proposal with the greatest reluctance, for August was regarded as a rake who had fathered no less than twelve illegitimate children. Wilhelm, who had not seen Elisa for three years, travelled to Poznan in February 1825, where they secretly became engaged.

Nobody in Berlin doubted any more that the wedding would indeed take place. Wilhelm drew up plans for his own castle in the park at Babelsberg, whilst Elisa dreamt of her new family status in Poznan. Servants turned up in the hope of being engaged by the future couple. Alarmed by the rumours of a marriage, the King once more called a conference at which his ministers emphasised that the marriage was not only undesirable, but also that an adoption would not restore Elisa’s equality in the aristocratic hierarchy. Meanwhile it had been announced that Crown Prince Friedrich would remain without an heir, and that Wilhelm would be responsible for the Hohenzollern succession. Whereas all Elisa’s women friends had long been married, she experienced the lengthy ordeal of waiting as a sort of exile. October arrived and Elisa celebrated her 22nd birthday in the new Antonin hunting lodge that Prince Radziwiłł had commissioned Karl Friedrich Schinkel to build for him in the Ostrowo district of the province of Poznan. Wilhelm had been forbidden to travel to Silesia. Instead, on the suggestion of the King, he travelled with his younger brother Carl to Weimar, where the 16-year-old Marie and her 14-year-old sister Augusta von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach were waiting for eligible partners.

Carl fell in love with Marie immediately. That said, the Princess’s mother, the Grand Duchess Maria Pawlowna, the sister of the Russian Czar and sister-in-law of Charlotte, would only agree to a marriage on the condition that Wilhelm agreed not to marry Elisa, a woman of unequal social status from a Polish family. When Czar Alexander I died in Moscow to be succeeded on the throne by Charlotte’s husband, Nikolaus I, after an officer’s revolt, Grand Duke Karl August von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach sent an ultimatum to the Prussian king in which he stated that a marriage between Carl and Marie would only be agreed to on condition that there were no links with house of Radziwiłł. Both men were basically agreed that the best solution was for the two princesses of Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach to marry the two princes of Prussia. Thereupon Friedrich Wilhelm III wrote a letter to his son Wilhelm in June 1826 in which he forbade him to marry Elisa. “The bond of love between Elisa and me has been dissolved – may her friendship with me remain – until death!”, wrote Wilhelm to both mother and daughter. Prince Radziwiłł felt deeply insulted by his family’s degradation and the fact that his daughter had been kept waiting for so long. But after writing some letters of outrage he thought twice and decided it was better not send them to the King.

Carl and Marie married in May 1827. One year later Wilhelm asked for the hand of Augusta, despite the fact that he was unable to feel any love for her. Death descended on the house of Radziwiłł. In September 1827 Elisa’s brother, Ferdinand, died of tuberculosis. Three months later Helene, the wife of Elisa’s brother Wilhelm, also died. This was followed one year afterwards by the death of their daughter, who was Elisa’s godchild. In June 1829 Wilhelm of Prussia married Augusta von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach (ill. 7), who was fully aware for the rest of her life that she would only be only an inadequate replacement for Elisa. In his final letter to Princess Luise Radziwiłł Wilhelm wrote: “You will always remain in my memory, you will always remain to me what you were, what you are! May God bless you! Yours eternally, your tender loving nephew, Wilhelm”. Following the 1830 November uprising in the Russian part of Poland, that had been led by one of Prince Radziwiłł’s brother-in-law’s, Prince Constantin Czatoryski, and his brother Michael Radziwiłł, the Prussian King relieved Prince Anton Radziwiłł of his post as vice-regent of the Grand Duchy of Poznan. In 1831 Elisa’s brother Wladislaw died of tuberculosis. Prince Anton Radziwiłł was released from service in the Prussian state in 1833 and died in Berlin in the same year.

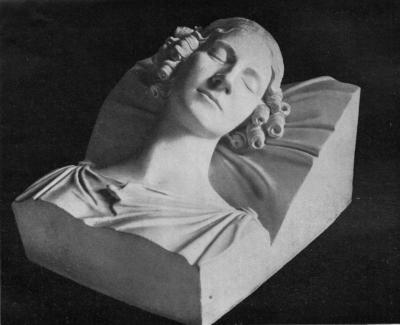

Elisa, who had ruined her health caring for her brother Wladislaw, as a result of which she was ill for years, died at Schloss Freienwalde on 27th September 1834 (ill. 8). In 1831 Princess Augusta of Prussia gave birth to a son, Friedrich, who was later to become the German Kaiser Friedrich III (the so-called 99-day Kaiser), and to a daughter Luise, the later Grand Duchess of Baden, in 1838. Wilhelm, who, even after his marriage to Augusta, met up with Elisa on several occasions, became King of Prussia in 1861 following the death of his brother, Friedrich Wilhelm IV. He was proclaimed the German Kaiser on 18th January 1871 in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles (ill. 9). The forbidden love between Elisa and Wilhelm not only fascinated the memoirs of contemporary witnesses, it has been the subject of a huge number of historical writings and novels. In 1938 it was even turned into a movie that was banned during the Nazi period, and finally shown in German cinemas in 1950 under the title “Liebeslegende” (Love Legends).

Axel Feuß, June 2016

PS:

This article basically follows the latest book on the theme by Dagmar von Gersdorff: “Auf der ganzen Welt nur sie. Die verbotene Liebe zwischen Princess Elisa Radziwill und Wilhelm von Preußen”, Berlin 2013; Insel-Taschenbuch 4393, Berlin 2015 / Dagmar von Gersdorff: Na całym świecie tylko ona. Zakazana miłość ksiȩżniczki Elizy Radziwiłł i Wilhelma Pruskiego, Jelenia Góra, 2014. The author evaluates the private notes of Wilhelm I of Prussia (1797-1888) in the “Geheimes Staatsarchiv zu Berlin”, as well as other documents related to the persons involved, and memoirs published by contemporaries.

Further reading:

Gräfin Elise von Bernstorff, geborene Gräfin von Donath. Ein Bild aus der Zeit von 1789-1835. Aus ihren Aufzeichnungen, 2 Bände, Berlin 1897

Oswald Baer: Prinzeß Elisa Radziwill. Ein Lebensbild, Berlin 1908

Elisa Radziwill: Ein Leben in Liebe and Leid. Unveröffentlichte Briefe der Jahre 1820-1834, herausgegeben von Bruno Hennig, Berlin 1911

Ernst Philipp Weigel: Elisa Radziwill. Das Drama der Jugendliebe Kaiser Wilhelms I., Leipzig 1911

Anne van den Eken: Kaiser Wilhelm I Jugendliebe: Prinzeß Elisa Radziwill. Historischer Roman (Aus dem Liebesgarten gekrönter und ungekrönter Häupter, 2), Leipzig 1913

Leo Hirsch: Elisa Radziwill. Die Jugendliebe Kaiser Wilhelm I, Stuttgart 1929

Kurt Jagow: Wilhelm and Elisa. Die Jugendliebe des Alten Kaisers, Leipzig 1930

Harald Eschenburg: Die polnische Prinzessin. Elisa Radziwill: die Jugendliebe Kaiser Wilhelms I., Stuttgart 1986

Marta Bzdręga: Prinz Wilhelm von Preußen und seine Jugendliebe Elisa Radziwill, in: Studia Germanica Posnaniensia, XXX, Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu, Poznań 2006, pp. 57-73