German-Polish Enthusiasm 1830

There is a long tradition of interest and sympathy for the sufferings of Poland beginning with the divisions of 1772. This tradition is particularly connected with the “friend of Poland” Karl von Holtei from Breslau. His musical “The Old General” (1825) and his famous saying “Do you think about it, my courageous Lagienka…” He not only followed the revolutionary tradition of France in the person of Napoleon, but transferred and associated it with the fate of the Polish freedom fighter Tadeusz Kościuszko. Here tragedy and the will to freedom united themselves with the fate of Poland after the three divisions, above all after the November uprising in 1830.

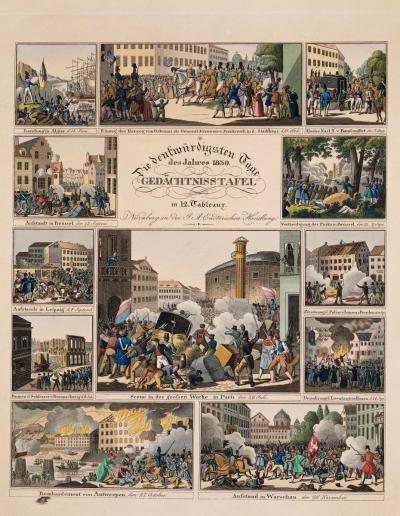

The Polish people had been repressed and their uprising was quickly recognised in Germany as part of a freedom movement throughout Europe. The Polish people gave the signal for the fight for freedom against repression. In the pre-March 1848 era Germans saw the Pole’s struggle as a symbol of their own yearning for freedom A popular illustrated broadsheet published in Nuremberg by Johann Andreas Endter included the events in Poland amongst other European uprisings which started with the July Revolution in Paris and spread like fire via Brussels to end in Russian-occupied Warsaw. The general public in Germany showed its sympathy from the start. Even when the popular picture papers in the Prussian area – like the illustrated broadsheet from Neuruppin in Brandenburg – kept their commentaries reticent and only documented the warlike events, it was not long before messages of sympathy were being shown throughout all parts of the German states: and these were registered in Poland.

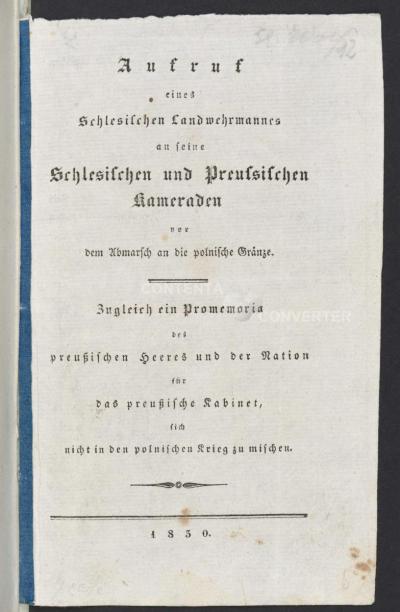

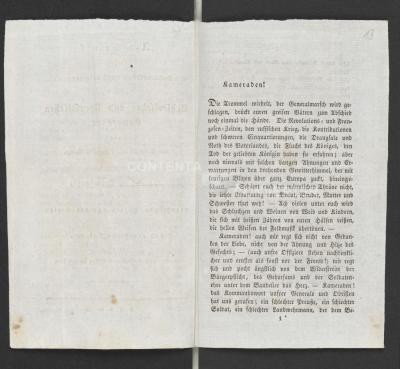

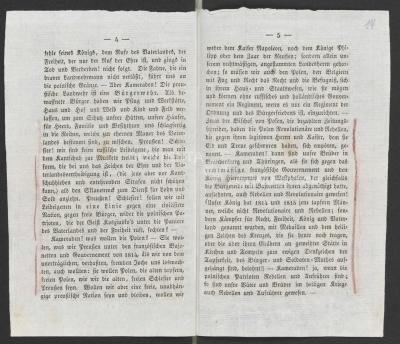

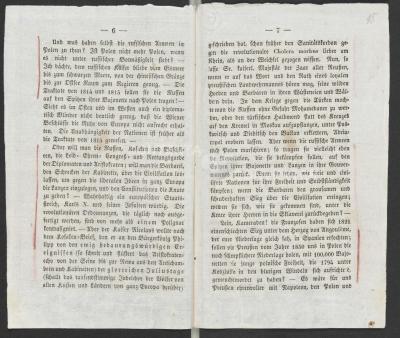

The appeals for solidarity appeared in anonymous flyers because the authors were afraid of censorship as a result of the Carlsbad Decrees. Thus one anonymous “Silesian soldier” called on “Silesian and Prussian comrades” not to fight against the Polish patriots of a “civilised nation”. The heroic Polish resistance to the czarist global power Russia was on many occasions compared with the struggle between David against Goliath. The Poles’ courageous opposition to a European world power was given even more strength by the knowledge that the two armies were completely unequally equipped. Here the Polish peasants’ scythes had been re-forged to make side-arms and these simultaneously symbolised the unequal battle and the will to freedom of the “common man” in the popular uprisings. 40 years previously the legendary uprising of Tadeusz Kościuszko had already laid the ground for the Germans’ image of Poland as a courageous country.

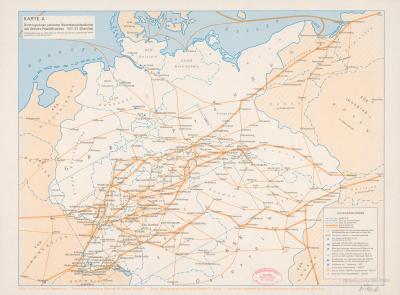

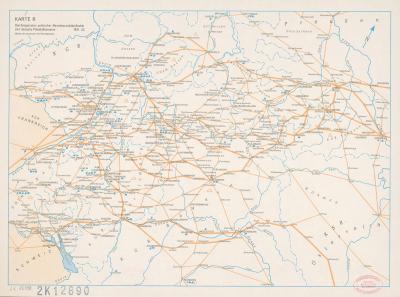

The speedy spread of news about the fall of Warsaw on 8th September 1831 to the Russian invaders and the subsequent sufferings of the population, all helped to bolster sympathy in Germany. The headlines on 15 September in the Munich journal Der deutsche Horizont read: “The Russians have invaded Warsaw on 8th September! On 8th September 17 people died from cholera in Berlin! Despotism has been victorious; freedom has come to an end! Woe! Woe! Woe!” The fate of the Polish elite, soldiers, officers, writers and artists who fled to Western Europe, especially to France, Switzerland, Italy and Great Britain is still known today as the “Grande Émigration” (polish Wielka Emigracja): the people in the German states, cities and villages were only too aware of this. Hence they set up aid organisations to support and welcome travellers by staging welfare events to feed them and provide them with the supplies they needed on their way westwards.

The routes clearly show that the refugees avoided Prussian areas, for Prussia had participated in the division of Poland and wished to avoid any unrest: the last thing it wanted was for the flame of revolution to spread into Germany. Even when the other German states followed this trend as a consequence of the reactionary Carlsbad Decrees (1819), middle-class associations and women’s initiatives in particular succeeded in circumventing the political bans.

The fate of the Polish patriots was impressively caught in a painting made in 1832 by Dietrich Monten entitled “Finis Poloniae or the Poles’ Farewell to their Fatherland in 1831”. This image of tragically defeated heroes was intended to accompany the Poles on their journey and inspire Germans to help them. The reception of the Poles in Leipzig still remains famous today: all the leading personalities in the city took part and the event was impressively documented at a later date, especially in the first performance (1836) of the young Richard Wagner’s “Polonia Overture” with its musical quotations from Poland. Traces of this can still be found in many places in Germany today; in Dresden, in Marburg an der Lahn and hundreds of other places, above all in south-west Germany. These events came to a peak in the Hambach Festival in 1832.

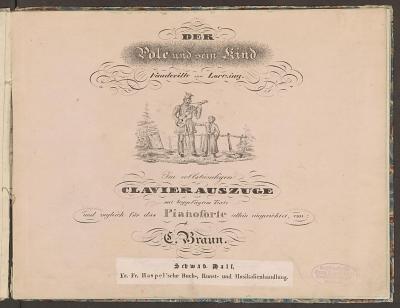

A huge number of contemporary souvenirs, lithographs and documents bear witness to the widely known “Poland Songs” about these events that remained in the consciousness of the German people until way into the 1880s. This was shown, for example by Theodor Fontane in his autobiographical novel “My Childhood Years” (1893/94). Positive attitudes to Poles then suffered a dramatic set-back both in German politics and also in the consciousness of the people: the decision in the Frankfurt Church of St Paul 1848/49, Bismarck’s “negative policies towards Poland” (Klaus Zernack) and the events following the First World War threw a shadow on German enthusiasm for Poland. Indeed this went into reverse when the Germans marched into Poland in 1939. A basis for rebuilding understanding between the two peoples after 1945 was created by meetings arranged by the German-German “Action Atonement” (starting in 1958), Willy Brandt’s knee-fall in 1970, and a commitment to the Solidarność movement in 1981: and all this gradually led to friendly neighbourliness. This is shown in such organisations as the German-Polish Youth Foundation, German-Polish associations, the Foundation for German-Polish Cooperation, the Kreisau Foundation for European Understanding and in the civil society initiative of the Weimar Triangle (along with France), as well as in many other initiatives.

Konrad Vanja, February 2015

Further reading:

Wolfgang Michalka, Erardo C. Rautenberg and Konrad Vanja (eds.), Polenbegeisterung. An article in the Deutsch-Polnischen Jahr 2005/2006 on the travelling exhibition Frühling im Herbst. Vom polnischen November zum deutschen Mai. Das Europa der Nationen 1830-1832. Berlin: Kupfergraben Verlagsgesellschaft 2005, with the help of Gerhard Weiduschat.

Anna Kuśmidrowicz-Król, Piotr Majewski, Konrad Vanja, Gerhard Weiduschat: Solidarność 1830. Niemcy i Polacy po Powstaniu Listopadowym – Polenbegeisterung. Deutsche und Polen nach dem Novemberaufstand 1830. Warsaw: Zamek Królewski and Berlin: Museum Europäischer Kulturen 2005/2006

Helmut Bleiber, Jan Kosim (eds.), Dokumente zur Geschichte der deutsch-polnischen Freundschaft, 1830-1832, Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1982.