Hamburg: Little Warsaw

Today Wilhelmsburg is a district in the middle of Hamburg. But in 1900 Wilhelmsburg was an independent parish where the proportion of Polish immigrants in the population rose to over 20% for a short time. It was then that the street called “Alte Schleuse” (Old Sluice) was nicknamed Little Warsaw.

The immigrants could not be officially registered as Poles, because Poland disappeared from the map of Europe between 1795 and 1918 and the country was split up between Prussia, the Russian Empire and the Habsburg Empire. Thus although immigrants from the East either held a Russian, Austrian or for the most part Prussian passport, they felt themselves to be Polish, maintained the Polish culture, and most of all their Catholic religion,. Most of them had come here in search of work and a better life. They came to Hamburg mainly from the region around Poznan. The majority of them were recruited by local firms. That said, it didn’t take much to lure Polish citizens to Hamburg. The political situation in their own land was dramatic, and the economic situation disastrous. As a result of an agricultural crisis at the end of the 19th century and increasing industrialisation many peasants had been reduced to eking out a meagre living by working on the land as day labourers. Hence their hopes for better employment prospects were much greater in Berlin, the Ruhrgebiet and Hamburg.

In comparison to the Ruhrgebiet, Polish migrants only began arriving in Hamburg relatively late, around the end of the 1880s. However, by the end of the 1890s the city contained around 5000 Polish immigrants, most of whom were young. By 1908 this figure had risen to 10,000 and five years later there were over 20,000. Many of them lived on the Elbe island of Wilhelmsburg – in 1897 two thousand, and in 1906 over 3000. And in 1913 there were over 6000 immigrants of Polish origin.

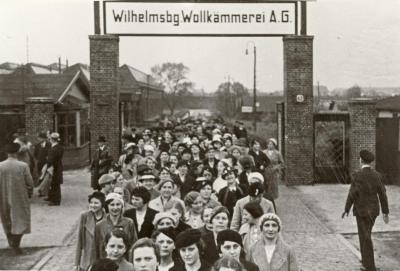

The men worked in the docks and factories, above all in the fishing, chemical and oil industries. They were often given the hardest and most dangerous work, like for example cleaning the ships of clamshells and algae. They carried rocks for the building trade and baked bricks in the brickworks, a backbreaking job in 12-hour shifts. The women were mainly employed in the Hamburg wool combing works. Here too the Polish women were given the hardest and most dangerous tasks: twelve hours on end without a break, under immense physical stress and always in danger of accidents and exposure to harmful materials. Most of the Polish women went out to work; a small minority were housemaids, and only very few worked as sales women or in the craft trade.

One Polish woman later recalled her work in Wilhelmsburg in the following manner: “I was employed in the wool combing works. Here almost all the workers were women. Men brought the raw wool which came in big ships all the way to the Reiherstieg (translator’s remark: a branch stream of the Elbe). It was terrible in the wool combing works because it was so hot. […] The machines were so loud that you couldn’t hear yourself speaking, let alone understand the other women. And when the foreman came round he was forced to bellow at us, otherwise we wouldn’t have understood a word. […] I also had to do my usual work at home, washing and cooking. We women often wondered how we managed it all. How did we get the work done?”

The women’s heavy physical labour and their inhuman working conditions led to dissatisfaction and anger, and in February 1906 this escalated to a strike in the wool combing works. Although the strike failed to improve their working conditions it did strengthen the Poles’ self-confidence. Stanislaus Svoboda, the son of an immigrant family, who had earlier been a peasant in Poznan, recalls the political atmosphere amongst the Polish immigrants: “The first thing when you got a job was to join the Union. The Poles were just as organised as the German workers. I can still say that today even though there’s a lot of things wrong with the Unions: you just can’t do without the Union! Polish immigrants, you might say, were born and bred into social democracy. They automatically joined the ranks.”

Polish immigrants were not only interesting to the Unions. Citizens of Poznan were also citizens of the German Reich. This gave them the right to vote and hence they were wooed by the political parties. True, the people of Poznan were Catholics and therefore tended to be conservative in their views, but in this point industrialisation led to changes. In those difficult times Polish workers no longer simply turned to the church for advice, but also to social democracy. The SPD recognised the situation. As a result the party sent Rosa Luxemburg to Wilhelmsburg for the 1903 election campaign to solicit the workers’ votes in Polish. Rosa Luxemburg didn’t have many problems in winning over the Poles to the Social Democrats, for Poles were amongst the poorest citizens in the city despite the fact that they worked so hard. They had scarcely any money, and were housed in appalling apartments, cellars and broken down shacks. It was quite usual for two families to share a small, dark, damp apartment. One contemporary witness remembers the housing shortage like this: “My mother went out to work, we were three children...What did people earn in those days? Starvation pay! So we took a man into the flat. He was on night shifts in the factory. When we were in school he slept in the children’s room. We lived in the “Industriestraße”, in the last house on the right. Chairs? I didn’t know what that was. We had a bench. That’s where we three children sat with our mother on the other side. And that was where we ate. We had two rooms, a tiny bedroom and a kitchen. We couldn’t afford three rooms. In the kitchen was a cupboard and a coal tub. We had a table and two benches.”

The Polish inhabitants of Wilhelmsburg lived in wretched social conditions. The situation only very gradually improved. The Polish community on the Elbe Island slowly increased. What bound them together was their membership of the Catholic Church, and it was not long before they called for a Catholic parish and pastoral care. Thus Polish immigrants took part in collecting money to build the church of Saint Bonifatius in Wilhelmsburg (Groß-Sand / Veringstraße). It was completed in 1898 and is still standing today. It was also thanks to the Catholic community that a private Catholic school teaching lessons in Polish was opened in October 1893 in Groß-Sand Street in Wilhelmsburg. At the same time the Poles set up two Polish/Catholic clubs, “St. Stanislaus” (in 1892) and “St. Joseph” (1894). In 1906 the parishioners of St. Bonifatius were given their very own priest: Father Styrinski from Kraków. At the same time he was the sole Polish speaking priest in the parish. His successor, who was appointed by the Episcopal Ordinariate in Hildesheim, could not speak Polish and this led to a public dispute between the parishioners and the Catholic authorities in Hildesheim. The parishioners were backed by their employers who realised that improved social structures were also to their advantage. Years afterwards the parishioners demanded to have a priest who could speak Polish, but their endeavours came to nothing.

Around this time secular associations began to arise. The “Klub Polski” was set up in 1887 and changed its name to “Nadzieja” (Hope) in 1888: it avoided political and religious matters and was more of a social club. At that time a Polish “Sokół” (Falcon) gymnastics club was almost obligatory and one was set up in Wilhelmsburg in 1905. Other clubs and organisations were mainly for women. As early as 1885 Polish women set up a club called “Wieniec” (Garland); this was followed by other clubs called “Wanda”, “Cecylia”, and “Halka”. Such clubs were mainly concerned with keeping up the Polish language and culture. All in all it might be said that Polish women were much more active than their men folk. In 1922 Polish women’s clubs in Wilhelmsburg had a total of 605 members. By comparison, the “Sokół” only had fifty. Club life played a central role in upholding the national and cultural identity of the Poles in Wilhelmsburg. One out of every two Polish immigrants in Wilhelmsburg belonged to Polish clubs before the First World War.

At the end of the First World War the situation for the Polish inhabitants and also for the “Prussian Poles” living in Germany changed radically. After 123 years without an independent state, the Polish Republic was proclaimed on 11th November 1918. According to article 91 of the Treaty of Versailles, signed on 28 June 1919, Poles in Prussia were duty-bound to decide whether they wished to retain German nationality or adopt Polish nationality and move to Poland. In fact they were able to make their choice until 1922. The majority of Polish immigrants opted for the Polish state. Wilhelmsburg was never again as Polish as it was in 1922. Today there is not much left to be seen of “Small Warsaw” in the old “Alte Schleuse” street. Nevertheless Wilhelmsburg is now a multicultural district, half of whose population are migrants. The names on the doorbells have been strongly “Germanised”: in addition, “Wischynsky” and “Pschybilla” occur at least as often as Turkish names like “Ölmez” and “Çiftçi”. Nowadays you cannot only witness traces of “old” Poland in the Hamburg suburb of Wilhelmsburg. The once so Polish locality is now attracting new Polish migrants like magic. Perhaps there is something Polish in the air in old “Small Warsaw”.

Adam Gusowski, March 2016

Additional information:

The passionate pleas of the Polish inhabitants of Wilhelmsburg in their dispute with the Episcopal Ordinariate to ensure that pastoral care be given in their native tongue is documented in a letter written in 1896: “Most venerable Sir! We should like to inform you that your sermon last month on 26th April can in no way satisfy us […] In the first place you are the very person who aggravates us the most. […] Here it is clearly only about working for money instead of eternal bliss […] Only because of money have you done everything possible to ensure that no Polish pastoral care can be allowed. Please do not think that we are not weighed down by the way you expressed yourself here, in words unfit for a house of God: "If it doesn’t suit you, you can look elsewhere". Here we should like to ask you where we should look? You are not an employer in a position to offer such a thing. Our employers themselves want us to find satisfaction in our church, and for this we should thank the directors of the wool combing works and no one else; for you know that we are grateful to them for our work. We would feel even more grateful if a Polish priest were here […] Yes indeed, Germanisation and moneybags now have priority. Why were the Holy Ghost and the apostles sent down to earth? Certainly not because of Germanisation, otherwise that would not have been necessary. Why were missionaries taught so many languages before they could preach the truth to heathens? And why should we not experience our mother tongue in God’s house? Because God clearly failed to create Polish people? […] Your fine sermon has thoroughly inflamed our spirits and we are not as satisfied as you clearly think. You will be hearing more from us if things don’t change soon; over the past four years we have been collecting dossiers crammed full of notes about what has been going on here […] Germanisation must at least be abolished in the church, […] For there before the throne of the Almighty everyone shall find full contentment rather than provocation […] Last not least we trust you will not forbid us to pray in our mother tongue, as Herr Rektor Wedig has forbidden the children and insulted our songs as Polish rubbish . […] Yes, father, the sweaty pfennigs you get from here were intended for a Polish priest, yes we even put it in writing. Since he has not now received them, it is as if they have been stolen. You will bear a heavy rock upon your breast until your final hours. We need a Polish priest here; you know that all too well. Now you will never be able to say I did not know. Today we wish to close with the following words: you have a huge responsibility, an enormous responsibility. Signed by the Polish citizens in Wilhelmsburg.”