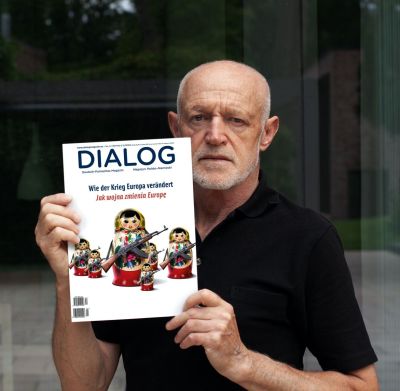

Polish surnames in Germany

How did Polish names come to Germany?

The first of three waves of immigration came after the partition of Poland (1772–1795). At the time, many people in what had previously been Polish territory became Prussian citizens and later German citizens. Others left their homeland, many to go to France, but some went to other German states. The second phase of immigration took place from the second half of the 19th century during the industrialisation of Germany. During this period, up to two million people (the sources here are divided) came to the growing industrial centres on the rivers Spree, Saar, Rhein and Ruhr. The Ruhr region even had a term for it - “Ruhr Poles”. They came from the eastern Prussian provinces of Masuria and Ermland, from Silesia, from the province of Poznań and also from Congress Poland, the Russian vassal state around Warsaw. The third immigration wave came after the Second World War and after 1989, when many people left the country for economic and political reasons, some of them as (re-)settlers.

Although around two thirds of Ruhr Poles left Germany again after 1918 (either to go to the newly founded Polish state or to the Belgian and French coal regions), they have left their mark on the surname landscape – as well as on the (pop) culture – of the Ruhr area today: Inspector Schimanski, expressions such as “My dear Kokoschinski”, Emil “Ämmil“ Cervinski from the “Kumpel Anton” stories by Wilhelm Herbert Koch, or the Ernst-Kuzorra-Platz in Gelsenkirchen are testimony to this. But there are also families with Polish roots who cannot be recognised by their surname. The Wichmanns, Dombrücks and also many Meiers may have been called Wichrowski, Dąbrowski or Majchrzak.

Changing names to avoid discrimination or to identify with Germany

But just who were “the Poles” around 1900? Many of the people who came from the Eastern regions of Prussia, didn’t consider themselves to be Poles at all, instead they identified as Prussians, as Germans. After all, they were Protestant and they had their own dialect, in contrast to the Catholic Poles. The Germans, however, could not distinguish them from other varieties of Poles and so the Masurians and the Warmians were discriminated against and called “Polacks”, just like the other recent settlers from the East (the term coming from the neutral self-description “polak” for Pole). It is these immigrants in particular that were more likely to stay after the 1920s. That is why they wanted, where possible, to avoid discrimination and to assimilate. One way to do this was to Germanise their surname.

The German state supported these attempts to assimilate. In many places, a document from the Ministry of Interior from 1901 was cited; according to the Ministry “tolerance is required when Germanising Polish names. [The Interior Minister] hopes that name changes of the intended type, which are suitable for supporting the melding of the Polish element with the German, will be given every support and facilitation by the authorities.”[1] During the period between 1880 and 1935, there were 30,000 applications to Germanise Slavic names in the Ruhr area alone. As early as 1937, however, it was also estimated that “today almost every fourth East German immigrant or their descendants have a German surname in place of their original Slavic name.”[2]

Just how names were Germanised differed greatly. The chosen methods ranged from adapting the spelling of the names to translating them. The examples given below show the different methods.

How were names adapted?

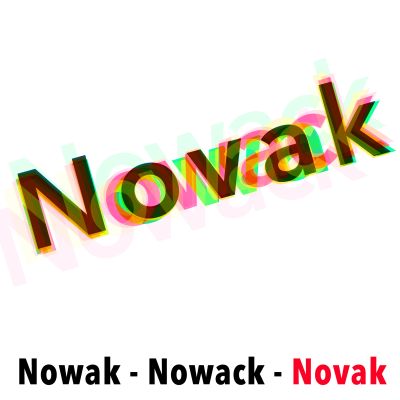

Adapting the spelling

The Polish language has several sounds which the German language does not have and the Polish alphabet contains several letters and letter combinations which do not exist in German.

The simplest method, therefore, is to get rid of the diacritical signs.

Zając -> Zajac

Szymański -> Szymanski

Kałuża -> Kaluza

But this is then sometimes accompanied by a blatant change in the pronunciation of the name. For example, Zając is actually pronounced [zajɔnts], broadly in German it is: Sajonts, with a soft s as in soup. But the pronunciation [tsajak] is typical for Zajac. Kałuża is originally pronounced [kawuʒa]; the letter ł is the same sound as the English w in water, and the ż is the same sound as the J in the German pronunciation of journalist.

[1] Quoted from: Neue Namen für polnische Arbeitsmigranten. Aus Majcrzak wird Mayer, in: Kulturbetrieb Mülheim an der Ruhr (Publ.): Das Gesicht der Migration in Mühlheim an der Ruhr zeigen, 16/08/2010, URL: https://web.archive.org/web/20170812103224/https://www.muelheim-ruhr.de/cms/neue_namen_fuer_polnische_arbeitsmigranten_aus_majcrzak_wird_mayer.html (last accessed on 07/06/2023).

[2] Franke, Eberhard: Das Ruhrgebiet und Ostpreußen. Geschichte, Umfang und Bedeutung der Ostpreußeneinwanderung, Essen 1936. Quoted from: Menge, Heinz: Namensänderungen slawischer Familiennamen im Ruhrgebiet, in: Niederdeutsches Wort. Beiträge zur niederdeutschen Philologie 40 (2000), p. 119–132, here 124.