A forbidden love – Princess Elisa Radziwiłł and Wilhelm of Prussia

The Radziwiłłs returned to Berlin once more for the winter season. The Prince’s “salon”, a regular meeting place for high society, was one of the most highly regarded salons in Berlin. Indeed it was one of the first salons where aristocrats and the middle class mixed together. This was where musicians performed their own works and aristocrats exchanged ideas and opinions with scholars, poets and writers. The Princess placed great value on her children taking part in adult life. Prince Anton Radziwiłł was widely regarded as a talented host and Grandseigneur who, according to Countess Elise von Bernstorff on the period between 1789 and 1835, was the personification of “German ingenuousness and Polish grace“, invited original personalities, Polish relations and friends, and was himself an outstanding composer. Dagmar von Gersdorff writes that, on one occasion when Goethe’s son August was invited, scenes from Goethe’s “Faust“ were presented for which Prince Radziwiłł had written compositions for soloists, choir and orchestra. The settings were designed by the architect, Karl Friedrich Schinkel. All the royal family turned up for the performance, including Prince Wilhelm. The guests also included Freiherr vom und zum Stein, General Gneisenau, Graf Brühl the director of the Berlin Opera, Bettina Brentano and many others.

In January and February 1820 Wilhelm began to visit the Radziwiłłs more frequently. In March the court chaplain and dean of the cathedral confirmed Elisa and her cousin Blanche von Waldenbruchbyx in the chapel of the royal castle, which the King had put at their disposal. This made Elisa eligible for marriage. Countess Bernstorff suspected that the King wanted to use the confirmation to be able to enable the young lady to become his daughter-in-law. It is possible that Wilhelm also thought along the same lines because he was inspired to declare his love for Elisa at Schloss Freienwalde in June 1820. Initially Wilhelm had no knowledge that reports and dossiers had been drawn up opposing any marriage bond with the Radziwiłłs. Nonetheless a number of people continue to work against him in the background. His sister Charlotte unexpectedly advised him to marry Princess Marie von Hessen. His adjutant Oldwig von Natzmer had a serious talk with him that resulted in his admitting it would be impossible to make any closer bond with Elisa without the King’s assent. The upshot was that when he finally saw Elisa when she was on holiday at Schloss Fürstenstein in Silesia his behaviour was withdrawn and frosty. This did not stop him from breaking into tears before Princess Radziwiłł when she took leave of him.

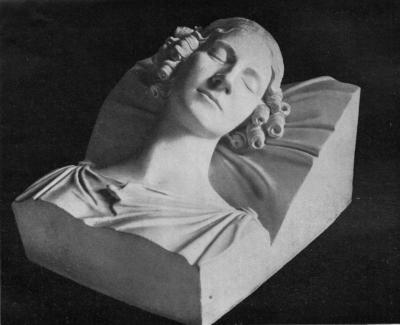

In January 1821 another theatre performance took place in honour of Princess Charlotte – now married and known as the Grand Princess Alexandra Feodorowna – in front of 3,000 guests in the White Hall of the Royal Castle. Here Elisa performed the role of the Goddess Peri in the oriental play “Lalla Rookh” by Thomas Moore. The painter Wilhelm Hensel was not only responsible for the sets and costumes but also painted Elisa in her role (ill. 6). Schinkel, Graf Brühl and the opera director Gaspare Spontini were also involved, the latter as a composer. Indeed Wilhelm, Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, and the Princes Wladislaw and Boguslaw Radziwiłł also had roles in the play. Elisa’s embodiment of “heavenly desire” struck a note with the romantic expectations of the audience and Wilhelm noted in his diary: “Magical, idealistic, an ethereal touch hung over the whole. Unforgettable!!! – E! – semper!” (i.e. “Elisa! For ever!”). By the second performance in February, at the latest, the former Police Minister Prince Sayn-Wittgenstein-Hohenstein, who was responsible for keeping tracks on the national and liberal movements in Prussia, had begun to see something more earthly in this “heavenly” romance. The upshot was that he demanded more information about the Polish family, Radziwiłł. Raumer drew up a second dossier in which he degraded the princely family to the status of minor Polish aristocrats. At the same time Elisa and Wilhelm were seen together at the silver wedding of the Radziwiłłs.

When Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm fell in love with a Catholic Princess from Bavaria – something which he should never have done because she was of the wrong religious denomination – the King decided to review Wilhelm’s marriage intentions once more. Raumer drew up two further reports which maintained that a marriage with Elisa was utterly out of the question. Police President Karl Albert von Kamptz, the head of the body responsible for repressing any liberal currents in society, wrote yet another dossier entitled “A Memorandum on the Legally Inappropriate Status of the Marriage of a Royal Prince of Prussia to Princess Radziwill”, in which he argued that Luise of Prussia who had become Princess Radziwiłł on her marriage, should have renounced any claim to the throne, including any claims from her descendants who of course included Elisa. When Wilhelm’s military adviser, Johann Georg von Brause, showed Raumer’s report to the Prince he was utterly flabbergasted. Wilhelm had never imagined that the Radziwiłłs would be out of the question because of their social status. He suspected that the real reason for the King’s rejection was a result of the disloyal attitude of some members of the Radziwiłł family towards Prussia. Amongst others, Michael Radziwiłł, the brother of Elisa’s father, had fought under Poniatowski and Kościuszko during the Polish uprising, and was subsequently a member of Napoleon’s army.

Wilhelm was told that if we refused to change his intentions the King would hand the matter over to a committee to examine the marriage of the Radziwiłł couple even more closely. People secretly accused Princess Radziwiłł of wanting to turn Elisa into a Prussian princess by marrying her off to Wilhelm. Pressure was put on Grand Duke Georg von Mecklenburg-Strelitz to have a serious word with Wilhelm because, if his brother Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm were to die without an heir, Wilhelm would then succeed to the throne. Thus, for reasons of state, he should renounce any thoughts of marrying the Polish princess. In February 1822 the King himself warned Wilhelm to put his private desires aside on the grounds of Hohenzollern family law, upon which Wilhelm promptly gave up any resistance. “It’s finished!! The precious, loving angelic being is lost to me!”, he noted. Nonetheless Wilhelm and Elisa continue to meet up at balls and on secret dates where they swore to remain friends forever.