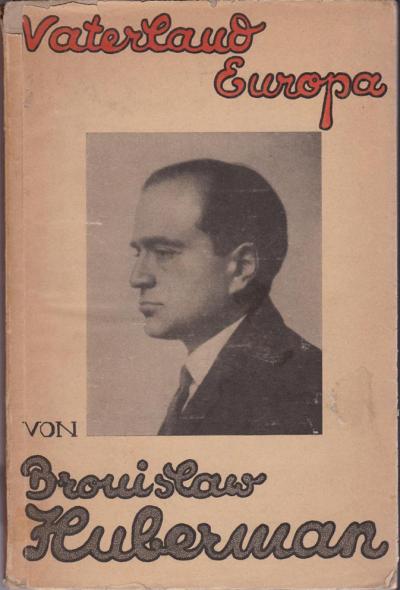

Bronisław Huberman: From child prodigy to resistance fighter against National Socialism

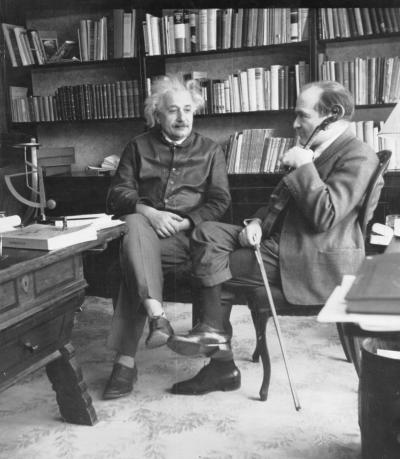

As a result of his years of engagement for the Pan-European idea and his own political convictions, Huberman, who travelled through numerous German towns during his concert tours, had a keen sense of the political developments there. In Berlin, Huberman was one of the few soloists “who was able to fill the philharmonic hall several times in one season with a solo evening”,[25] recalled Dr Berta Geissmar, Furtwängler’s executive secretary and “right hand”.[26] Huberman could not escape the anti-Semitism that had been on the rise since the beginning of the world financial crisis in October 1929 among the petty bourgeoisie in Germany, the German National People’s Party and, of course, the National Socialists. The hostile attitude towards Jews became almost pogrom-like during the attack on the Berlin Warenhaus Wertheim by supporters of the NSDAP, which took place on the occasion of the opening of the Reichstag on 13 October 1930, and during the anti-Semitic attacks by the SA during the Kurfürstendamm riot in September 1931. In the previously cited article from October 1932 in the Neue Leipziger Zeitung, Huberman noted with concern that lately people in Germany “are enthusiastically worshipping the confinement, are wanting to remain huddled together within limited bounds; that is the new religion of one Adolf Hitler, who, although a foreigner himself until recently, is bubbling over with ‘nothing other than being German’ and has written class hatred and ethnic hatred on his flag.”[27]

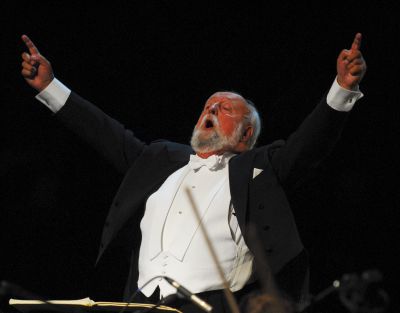

The fact that Huberman’s fears were justified was proven soon after power was transferred to the National Socialists. On 1 April 1933, they called for the first time for Jewish businesses, department stores, banks, doctors’ practices, lawyers and notaries to be boycotted and a few days later, with the enactment of the Law for the restoration of the professional civil service, started to remove Jewish civil servants from the civil service. Furtwängler, as reported by Geissmar, who was herself a Jew, always declared publicly and “unequivocally that the German music scene would soon be completely paralysed if it were to be regulated based on racial considerations”.[28] A large number of the great soloists and conductors were Jews as were many of the outstanding orchestra musicians. Jewish lawyers, doctors, academics and financiers, who themselves made music and supported the music industry, made up a significant portion of the audience. During the first concert tour of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in spring 1933 after Hitler came to power, there were open conflicts with the Nazis among local musicians, in the audience and at receptions in various German cities, such as Mannheim and Baden-Baden. In Paris, Marseille and Lyon, the orchestra met with hostility and threats of boycott because of the German Jewish policy, although Furtwängler was repeatedly able to demonstrate that Jews were not marginalised in his orchestra. However, numerous conversations between Furtwängler, Hitler, Reich propaganda minister Goebbels and “more minor party leaders“, in which the orchestra director warned “of the disastrous consequences of their race and party policies on Germany’s cultural life”,[29] did not have any lasting impact.

[25] Geissmar 1985 (see Literature), page 113

[26] Fred. K. Prieberg: Berta Geissmar – Versuch einer Vergegenwärtigung (1985), in: Berta Geissmar 1985 (see Literature), page II

[27] Huberman in the Neue Leipziger Zeitung dated 23 October 1932 (see Note 2), cited from von der Lühe 2004 (see Literature), page 70

[28] Geissmar 1985 (see Literature), page 77

[29] Ibid, page 84