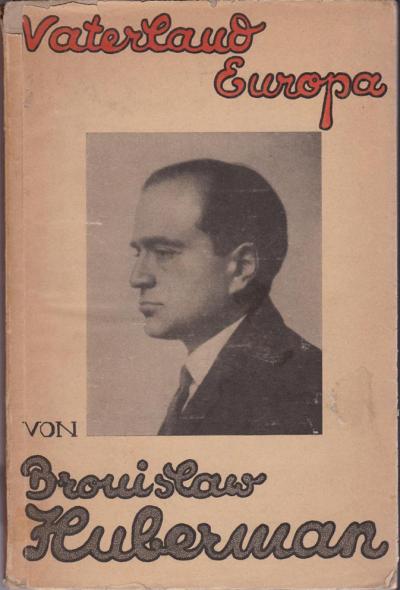

Bronisław Huberman: From child prodigy to resistance fighter against National Socialism

In a detailed letter dated 10 July 1933, Huberman responded to his “dear friend” Furtwängler and the next day asked if he may be allowed to publish this response in the international press. Although Furtwängler did not agree to this (“the consequence would surely be that you […] would perhaps no longer by allowed to perform in Germany at all”[34]), Huberman sent copies of his letter to Louis P. Lochner (1887-1975), the head of the Berlin office of the Associated Press, in the hope that the letter would be published in the New York Times. Lochner, who was to stay in Marienbad ten days later, managed to get the public version of the letter published in the Prager Tagblatt on 13 September 1933 (Fig. 8). The next day, an English translation appeared in the context of an article in the New York Times by the American journalist Frederick T. Birchall (1871-1955) under the headline “Huberman Bars German Concerts”.[35]

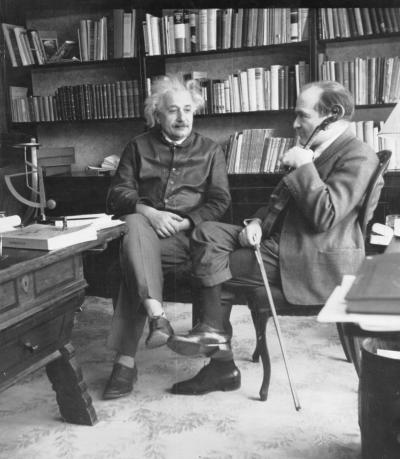

In his letter, not only did Huberman appeal to the conductor Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957), who had recently declined to participate at the Bayreuth Festival because of the anti-Jewish and anti-foreigner sentiment in Germany, he also expressed his admiration for Furtwängler “for the fearlessness, tenacity, sense of responsibility and tenaciousness” with which he had carried out his “campaign that he had begun in April to rescue concert life from the threat of annihilation by the race cleansers”. However, Huberman felt that the assurances negotiated with Reich Minister Rust about select artists participating in the German music scene based on the “principle of performance”, which the Prager Tagblatt cited in detail, could “not be considered a sufficient basis” for him “to be part of the German music scene again”. The “selection principle” smacks of the intention “to continue to apply the unthinkable, race selection, to all other areas of culture.” Whilst there was to be an exemption for music, museum directors, researchers and teachers would continue to be marginalised. The “few foreign or Jewish musicians called upon to participate” were only there to “be paraded before the whole world to show that all is well with culture in Germany. In reality, however, German thoroughness would keep on applying new definitions about racial purity to immature art lovers, schools, laboratories etc.”