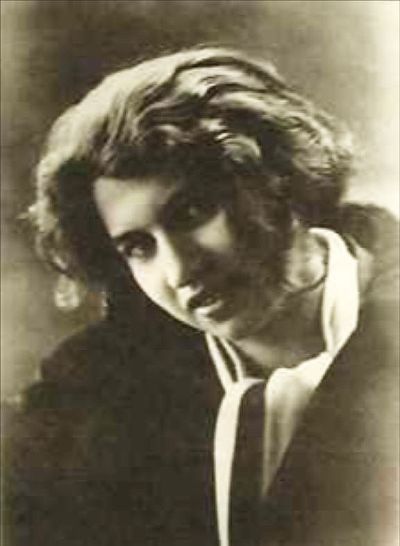

Dora Diamant – activist, actress, and Franz Kafka’s last companion

Back in Berlin – member of the KPD

After her term of employment with the theatre came to an end in April 1929, Diamant returned to Berlin, where she found a place to live in Lohmeyerstraße, to the east of Charlottenburg Palace. Her apartment was situated in the triangle between the KPD-dominated workers’ district on Klausenerplatz square and the “Kleiner Wedding” area behind the Deutsche Oper opera house and “Roter Wedding”, the traditional electoral stronghold of the Social Democrats and communists. Her flatmate, “Eva Frietsche [...] a very active communist”, probably Eva Fritzsche (1908–1986), assistant to the theatre manager Erwin Piscator (1893–1966) and from 1930 member of the KPD, took Diamant with her to “cell evenings” in a communist “Cell 218",[94] a group close to the KPD which was dedicated to the abolition of Paragraph 218, which dealt with abortion. The KPD had garnered new members not least after the May riots from 1 to 3 May 1929, also known as the “Blood May” (Blutmai), when the Social Democrat Berlin police president Karl Zörgiebel gave orders to shoot at the demonstrating workers.

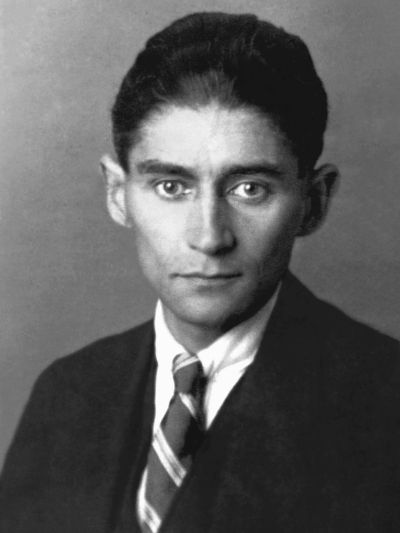

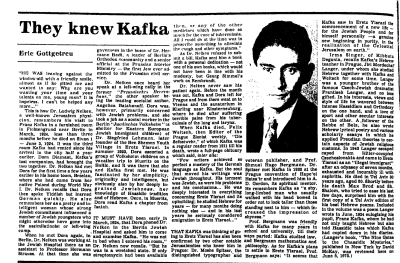

Diamant continued to apply for theatre work and became politically active in the KPD. She produced and distributed leaflets and helped organise demonstrations and rallies. In January 1930, she was officially accepted into the KPD “street cell” that was responsible for her, under the codename “Maria Jelen”. However, her fellow activists were dissatisfied with her level of commitment. Later, a section head of the party reported to Moscow that she received “financial support from the estate of her first husband (Franz Kafka) via the left-wing bourgeois Zionist writer Max Brod”.[95] Brod, who during this time was being attacked in the “Vossische Zeitung” for publishing Kafka’s estate without Kafka’s approval, received support from Diamant in the form of letters to the editor and personal visits to the newspaper. While her relationship with Brod deteriorated as a result, she still received royalties from him from Kafka’s works in May 1930.

In the summer of 1930, she was accepted into the KPD division for Soviet-style Agitprop theatre groups, which had been formed from 1925 onwards. The division, which was led by Erwin Piscator, supported the party with street theatre productions during election campaigns and workers’ strikes. Diamant was responsible for training the amateur actors, and as part of the Revolutionary Union Opposition (Revolutionäre Gewerkschafts-Opposition, RGO), she finally joined the RGO film, stage and music group (RGO-Gruppe Film-Bühne-Musik). The activities of the Agitprop groups, without which no KPD event was now conceivable, reached their highest level in the months leading up to the Reichstag elections in September 1930. They registered over 1,000 new members and reached an audience of nearly 200,000. From 1932 onwards, they were gradually banned.

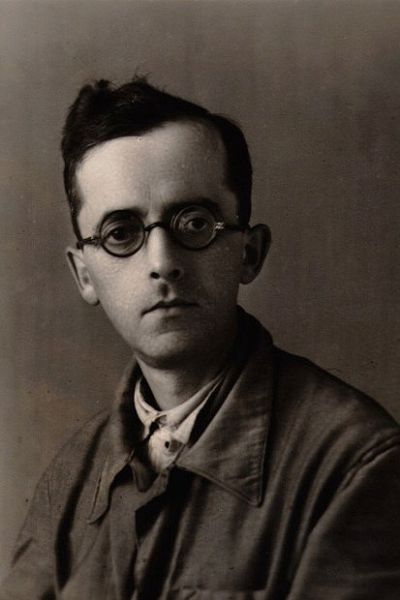

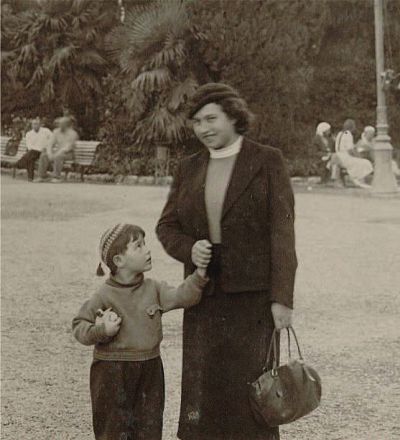

After moving to the district of Zehlendorf in February 1931, Diamant was active as an organisational and political leader in the party cell that was responsible for her. She allowed her apartment to be used as a venue for a “ten-day school” (Zehntageschule) for the curriculum teachers at the Marxist Evening School (Marxistische Abendschule), in which she herself took part. It was during this time that she met the graduate economist Lutz (Ludwig) Lask (Fig. 14), son of the author Berta Lask, who was five years younger than her, and who taught Marxist economic theory. After completing his studies at the Institute for Global Economics (Institut für Weltwirtschaft) in Kiel, Lask had returned to Berlin, and at the suggestion of his mother and younger brother Hermann, joined the KPD in the Lichterfelde-Ost district. The Lask family – Berta and her husband, the Jewish neurologist, brain scientist and Social Democrat from Bromberg, Dr. Louis Jacobsohn (1863–1940) and their five sons and daughters born between 1902 and 1906 – lived in a large villa in Lichterfelde. Some time later, Diamant moved in with the family, and married Lask on 30 June 1932. As well as being part of the large family, which also included sons- and daughters-in-law and grandchildren, and in which regular discussions were held on topics ranging from economics and culture to politics and philosophy, Lutz and Dora also worked in the KPD street cell, distributed leaflets and newspapers and organised demonstrations and secret meetings.[96]

When Adolf Hitler became Reich Chancellor on 30 January 1933, their membership of the KPD became a real threat to their personal lives. The “Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of People and State” (Verordnung des Reichspräsidenten zum Schutz von Volk und Staat) issued by Hindenburg on 28 February 1933 following the Reichstag fire, also known as the “Fire Decree” (Notverordnung), led to restrictions that affected personal freedom, the right to free expression of opinion, press freedom and the right to form an association or a gathering, and permitted violations of postal secrecy, the organisation of house searches and seizure of personal property beyond the remit of the current laws. At the beginning of March, the KPD tasked Lutz Lask with illegally publishing its central organ, “Die Rote Fahne” for the Steglitz district. Like the leaflets and handbills, the newspaper was produced on small printing presses in back rooms, attics, and cellars. The Gestapo suspected the 70-year-old Jacobsohn of having distributed “documents against the state”, while four members of the Lask family were arrested, among other things for their participation in illegal KPD meetings. The villa was searched, and items were confiscated, including the documents belonging to Kafka. Lutz Lask was tortured and interrogated for four days before being released. Following their release, his brothers Ernst and Hermann applied for permission to travel to the Soviet Union. Berta Lask was taken into “protective custody” for one month.[97]

After the boycott of Jewish shops, medical and legal practices from 1 April and the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service (Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums) issued on 7 April, which legislated against the continued employment of non-Aryan civil servants, the Lask family’s Jewish origins meant that their existence was now under threat. Lutz continued to publish the “Rote Fahne” until the summer of 1933. In their attempts to evade the Gestapo, he and Dora moved from one apartment to the next in different districts of Berlin. All the time, they remained “in contact with the Party” and “were dedicated to the production and dissemination of leaflets, and to newspapers, arranging meeting points, demonstrations”.[98] In June, Berta Lask emigrated to Prague. Jacobsohn was dismissed from his teaching work at the university. In August, Lutz was arrested by the Gestapo in the Schöneberg district. He was kept in the Gestapo prison in the Columbia-Haus, where he was tortured and sentenced to eight months “protective custody” (Schutzhaft). In October, his sister Ruth went into exile in the Netherlands with her family.

[94] Komintern file Dora Diamant (see note 88); see Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 207, 209 f., 241.

[95] Komintern file; ibid., page 211.

[96] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 207–220.

[97] Gestapo report from 1937, Berlin State Archive (Landesarchiv Berlin); Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 223–226.

[98] Komintern file Dora Diamant (see note 88); Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 229.