Jesekiel David Kirszenbaum (1900–1954). Student of the Bauhaus

“What other children were allowed to do, was off limits for me”, writes Kirszenbaum in his memoirs about his childhood and youth in Staszów.[1] As the youngest child of the rabbi Natan Majer Kirszenbaum and his wife Alta, née Ledermann, his calling was to be a rabbi, so it was not becoming for him to take part in the other children’s games. In the Cheder, the religious primary school, his interest was awakened by the fantastically embellished stories of the Chumasch, the five printed books of the Tora, and the folk legends in the Sefer ha-Jaschar, the mediaeval Book of Jashar, whilst the Talmud and its commentaries bored him. He lived in a dream world and longed for stories full of imagination and creativity. After he lost both his older brothers to illness at the age of 10 and 13, his parents started to embrace fanatical religious beliefs whilst he lay in the meadow, daydreaming and thinking about things that only existed in his sub-conscious, instead of immersing himself in the Talmud in the Beth Midrasch, the study room.

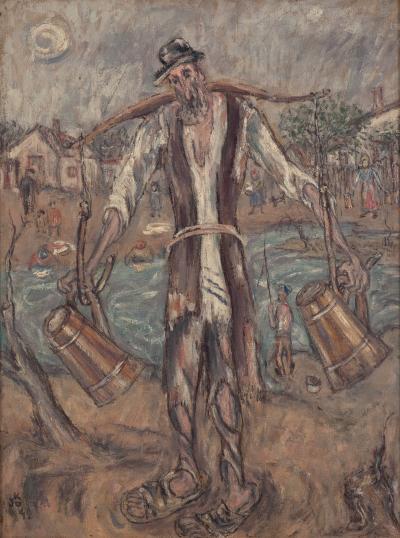

What made him happy was the way of life of the simple Jewish people, the wandering musicians with their parrots who played at the Jewish festivals, and the load carriers and water carriers with their colourful robes. He felt the urge to draw, especially portraits, which was forbidden because of the Jewish prohibition on representing living forms in images, and for which he was hit by his father. In Staszów during the First World War he experienced at first hand the Cossacks passing through his village and the Jewish pogrom. He also saw Austrian and German troops, plundering and murdering Tsarists, who took Jews away with them. When he was sixteen or seventeen, he began to read classic Yiddish authors like Jizchok Leib Perez (I.L. Peretz) and Spinoza and became an Epikoros, a critic of the Jewish religion. He hung around with his friends and with girls, became a member of the socialist-zionist Hashomer-Hatzair youth movement, was hit by his parents again and fled to relatives in the neighbouring village.

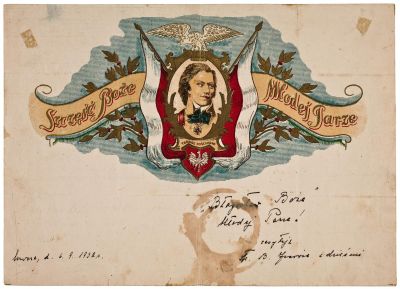

Having returned to his parents, he started reading books and drawing again. His portraits of Jewish ideologists Theodor Herzl, Karl Marx and Wladimir Medem hung in the clubs in Staszów and the surrounding towns, and his portraits of Yiddish authors Mendele Moicher Sforim, Scholem Alejchem and Perez hung in the local library (Fig. 1).[2] He made a second attempt to escape with the intention of studying art in Krakow, but failed because of his lack of money and education. When he returned home again, his relationship with his parents improved. In 1920, when he was due to be drafted into the Polish army during the Polish-Soviet war, he sold everything he owned to finance his journey to Będzin[3] on the border with Upper Silesia in Prussia and then his escape to Germany.

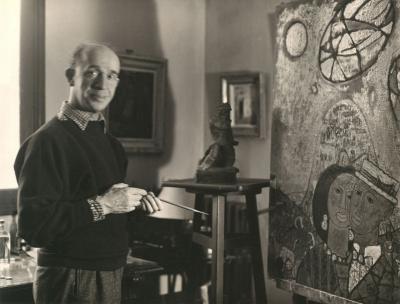

It is not known how exactly Kirszenbaum finally arrived in the Ruhr region. Like more than half a million Ruhr Poles who had emigrated there since the foundation of the German Reich, he earnt his money as a mine worker and from 1920 lived as a tenant in Duisburg, as evidenced by a postcard to his family[4]. He gave Hebrew lessons on the side, but must also have been working as an artist. The art historian August Hoff (1892-1971), who later became the director of the Duisburg Museum of Art/Duisburg Kunstmuseum, became aware of Kirszenbaum, urged him to study art and apparently found him a place at the State Bauhaus/Staatliche Bauhaus in Weimar. Kirszenbaum began his studies there in 1923 in the preliminary course given by Johannes Itten and, during the following three semesters, also attended courses given by Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee. He later wrote that Kandinsky and his clarity of thought had had the greatest influence on him. In particular, Kandinsky moved him from a formalistic style of painting to figurative painting, in contrast to his own artistic interests.[5] He is said to have maintained a collegial connection to Klee. Klee influenced him with his “inner world” and the diversity and endlessness of his dream images.[6] When political pressure meant that the Bauhaus was closed down at the turn of 1924/25 and moved to Dessau, Kandinsky is said to have earmarked him for a lecturing post at the new site, which ultimately failed to transpire following opposition from the Director, Walter Gropius.[7]

[1] Jechezkiel Kirszenbaum: Childhood and Youth in Staszów, in: J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see Literature), page 129

[2] ibid., page 155

[3] ibid., page 167 f.

[4] J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see Literature), page 49

[5] ibid., page 48

[6] ibid., page 49

[7] Linsler 2013 (see Literature), page 293. Linsler refers to an essay by Ernst Collin: J.D. Kirschenbaum, in: Exhibition Catalogue from Galerie Fritz Weber, Berlin 1931 [Bauhaus Archive, Inv. No. 2239], to an essay by Frédéric Hagen: J.D. Kirszenbaum = Exhibition Catalogue from Galerie Karl Flinker, Paris 1961, and to the article by Hanna Bartnicka-Górska: Jecheskiel Dawid Kirszenbaum, in: Słownik Artystów Polskich i obcych w polsce działających. Malarze rzeżbiarze graficy, 3, Polska Akademia Nauk, Instytut Sztuki, Warsaw 1979, page 412. Ernst Collin (1886-1942 murdered in Auschwitz) was a bookbinder, author, art editor and antiquarian from Berlin, see https://www.stolpersteine-berlin.de/de/biografie/6661. See below for more on Frédéric (Friedrich) Hagen.

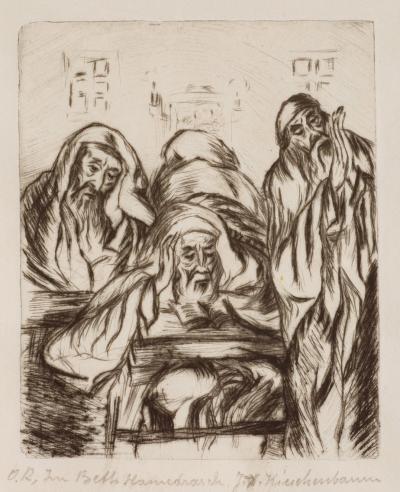

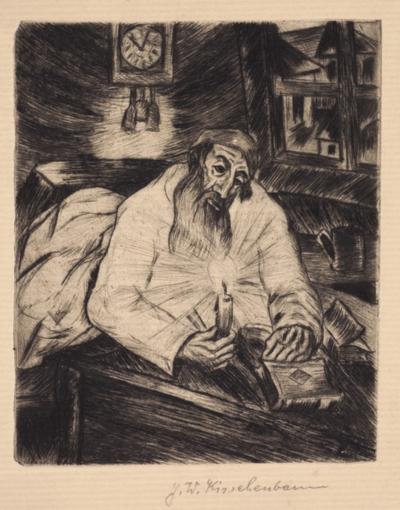

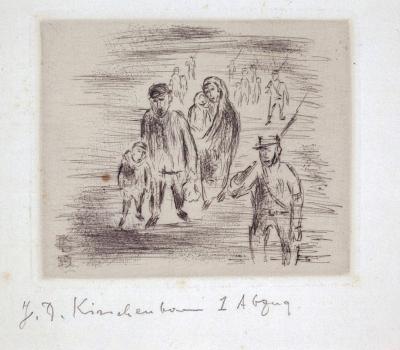

Instead, Kirszenbaum went to Berlin in 1925 where he worked as a freelance artist for the next eight years. He stayed in contact with his fellow students from the Bauhaus. They included the painter, illustrator and photographer Paul Citroen (1896-1983), with whom he had studied in Itten’s preliminary course and who hailed from Berlin, where he had also worked as a freelance artist from 1925 before leaving for Amsterdam via Paris and Basel in 1927. Also amongst them was Citroen’s sister-in-law, Ruth Citroën (1906-2002),[8] née Margarete Vallentin, who until 1923 had worked in the carpet weaving workshop at the Bauhaus and who had married the aspiring Berlin fur trader Hans Citroen (1905-1985), Paul’s brother. In December 1925, an etching by Kirszenbaum appeared in the Berlin magazine International Advertising Art. Monthly Magazine for Promoting Art in Advertising/Gebrauchsgraphik. Illustratoren. Monatsschrift zur Förderung künstlerischer Reklame, the official organ of the Association of German Advertising Artists/Bundes Deutscher Gebrauchsgraphiker. However, the etching entitled “In the Beth Hamedrasch” (Fig. 7) appeared with the title “Illustrations for Jewish novella” and under the new pseudonym “J. Duwdiwani”, the Hebrew word for “Kirschbaum (cherry tree)”, and with the German spelling of the surname “Kirschenbaum” added in brackets.[9] At that time, the artist was living in Kantstraße 114 in Charlottenburg.[10] In the same year he created umpteen further drawings and etchings showing scenes from Jewish life (Fig. 6, 8-10).

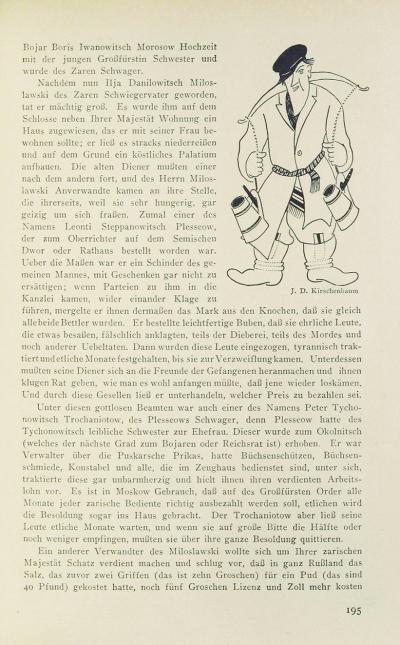

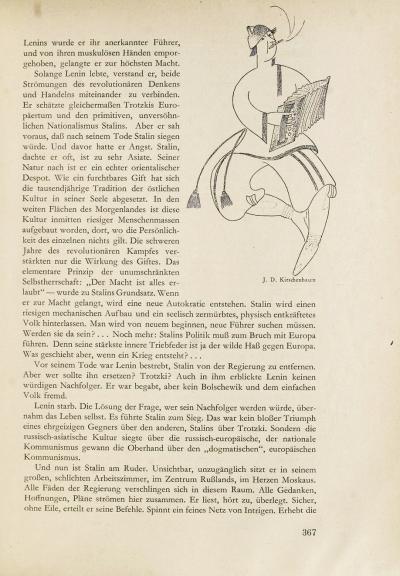

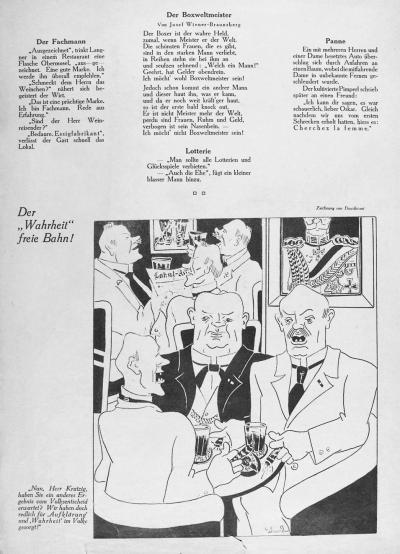

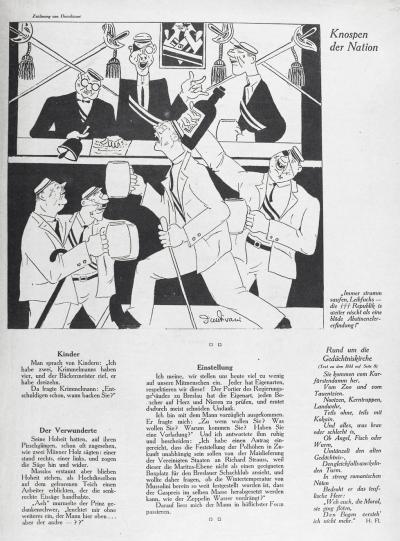

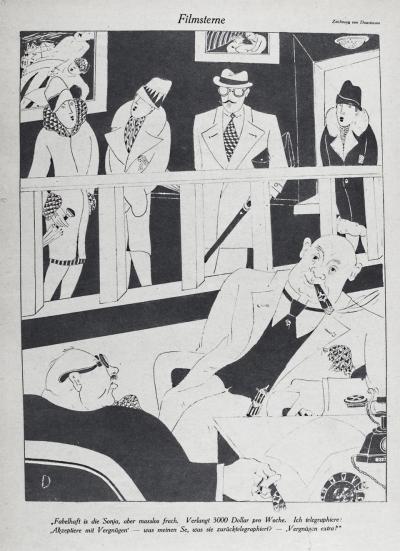

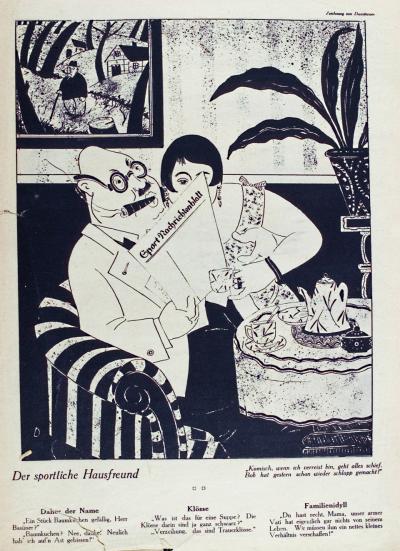

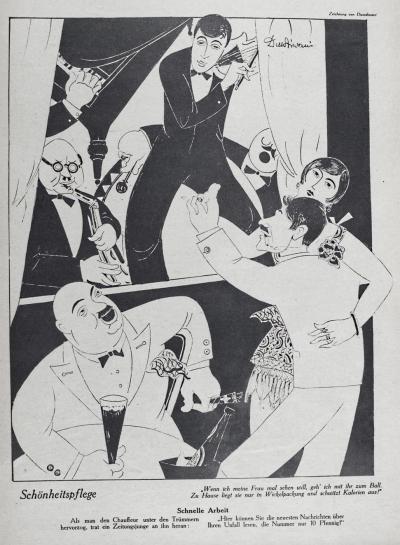

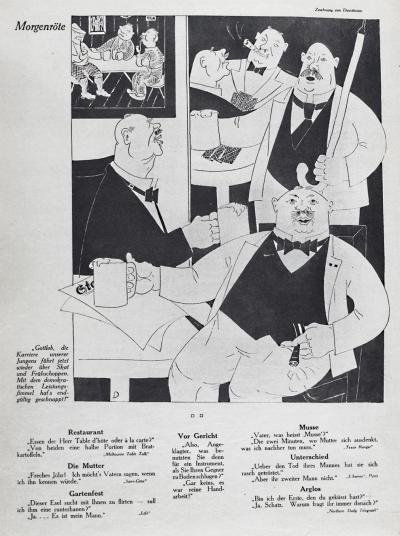

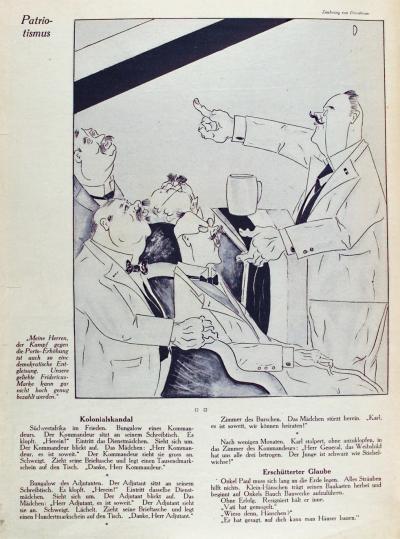

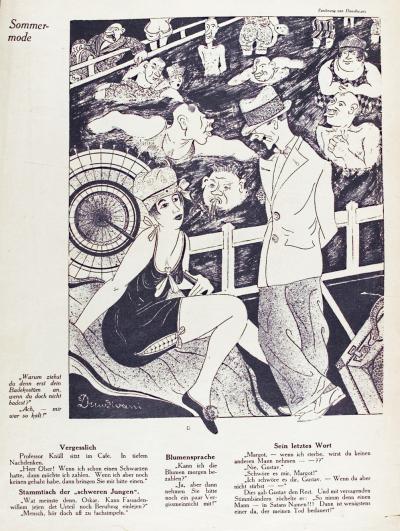

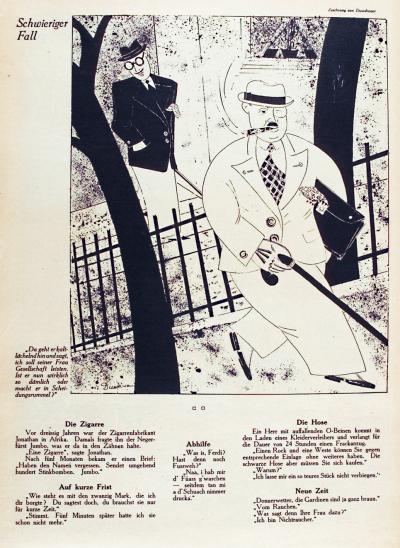

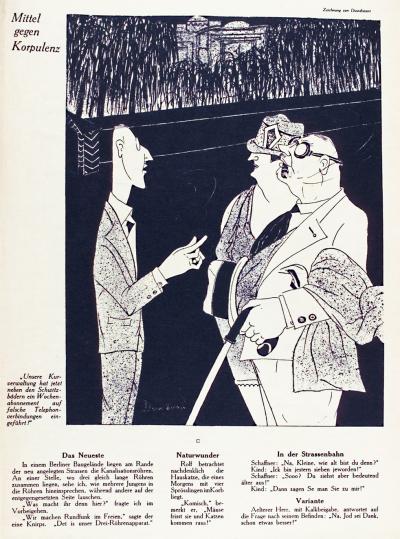

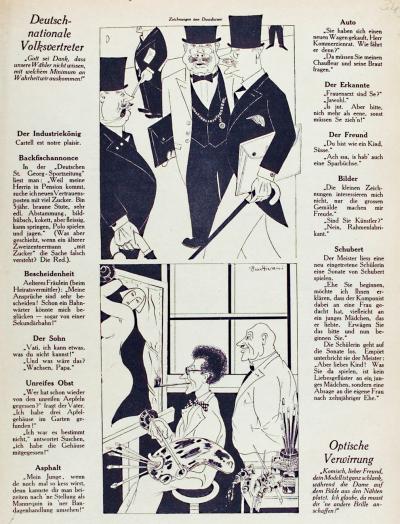

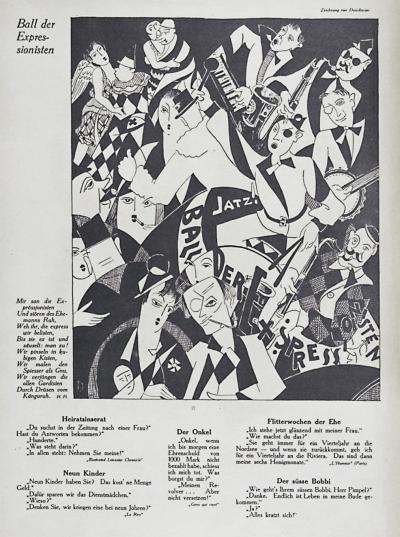

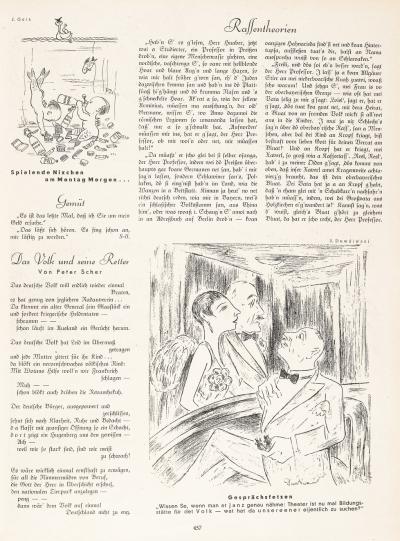

At the beginning of 1926, the artist was commissioned to provided illustrations and cartoons for the satirical magazine Ulk, an independent weekly publication from the liberal Berliner Tageblatt. Both media organs were part of the Berlin publishing group Rudolf Mosse and had close ties to the left-wing liberal German Democratic Party/Deutschen Demokratischen Partei (DDP). Ulk had been around since 1872 and from 1918 to 1920 was under the leadership of Kurt Tucholsky. Until 1922 it appeared as a free supplement in the Berliner Tageblatt and the Berliner Volks-Zeitung. From 1926 the Tageblatt ran at a loss so Ulk was only enclosed occasionally as a free supplement. The first four illustrations by Kirszenbaum bearing the signatures “D” and “Duwdiwani” appeared on 19 February 1926. They were harmless social satires, including an “expressionist politician”,[11] for which the editorial team usually invented the texts and captions. During the three years or more that he worked for them, twenty nine pages on which one or more of Kirszenbaum’s satirical illustrations or cartoons were printed appeared in Ulk up to 17 May 1929 (Fig. 15-31).[12] He presumably stopped working there for financial reasons because Ulk was already insolvent at this time.

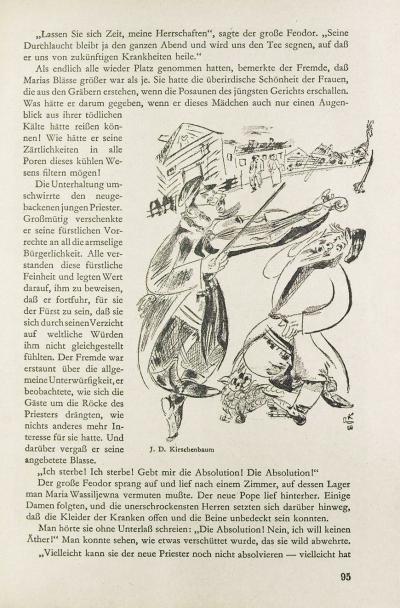

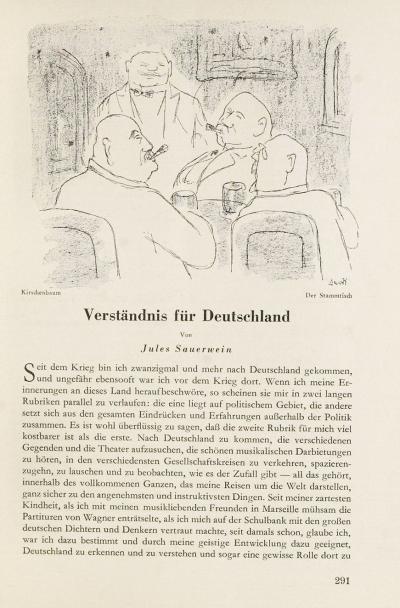

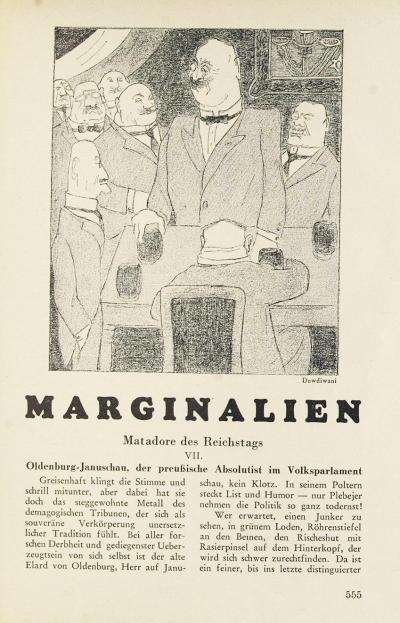

From July 1926, more of Kirszenbaum’s illustrations appeared in the culture and zeitgeist magazine Der Querschnitt, which was founded by Alfred Flechtheim in 1921 and published by Hermann von Wedderkop for Hermann Ullstein under the Propyläen Publishing House/Propyläen Verlag.[13] These illustrations mainly involved stylised figures in traditional Russian or Jewish costume which were consistent with the respective literary articles, such as in the essay by Darius Milhaud entitled “Musical life in Soviet Russia”,[14] a mother and child and a drinking scene in an article by Adam Olearius entitled “The first Russian Revolution (1656)”,[15] a water carrier in the same text (Fig. 12), a harmonica player as an illustration for an essay by S. Dimitrijewski entitled “Stalin – The rise of a man” (Fig. 13), and a Jewish fiddler, just as Kirszenbaum remembered from his time in Staszów, in a Russian novella by Ramon Gomez de la Serna entitled “Maria Wassiljewna” (Fig. 14). In all, ten illustrations appeared in Querschnitt in 1926, 1927, 1929 and 1931, the most recent being two full cartoons, “The table of regulars” (Fig. 35) and a drawing depicting old men in official clothing in front of the old imperial flag (Fig. 36) to accompany the multi-page commentary entitled “Matadors of the Reichstag” by an author with the pseudonym “O.B. Server”. The editorial department at Querschnitt may have acquired a whole bundle of Kirszenbaum’s drawings at an earlier point in time because the fiddler from Staszów (Fig. 14) and a farmer with pig and geese in the basket[16] are obviously dated “26” with the initials “JDK” barely legible, but they didn’t appear until 1929 and 1931 in the relevant contexts.

[8] Letter from Ruth Cidor-Citroën to the Goethe Institute Paris dated 23 September 1969, Archive of Nathan Diament, Tel Aviv. The amicable relationship is also evidenced by letters and postcards from Kirszenbaum to Paul Citroen in Amsterdam from 1930, which can be found in the Bauhaus Archive, Inv. No. 8034/119, 120, 122; Goudz 2012 provides more detail (see Literature), page 533 f.

[9] International Advertising Art. Monthly Magazine for Promoting Art in Advertising/Gebrauchsgraphik. Monatszeitschrift zur Förderung künstlerischer Reklame, Volume 2, Issue 6, Berlin 1925, page 82, online resource: https://www.arthistoricum.net/werkansicht/dlf/157261/88/?tx_dlf%5Bhighlight_word%5D=Kirschenbaum. His pseudonym is rendered there incorrectly as “Duwdiwam”.

[10] ibid., page 2, online resource: https://www.arthistoricum.net/werkansicht/?id=10809&tx_dlf%5Bhighlight_word%5D=Kirschenbaum&tx_dlf%5Bid%5D=157261&tx_dlf%5Bpage%5D=4

[11] Ulk. Weekly Publication of the Berliner Tageblatt, 55th Edition, No. 8, 19 February 1926, page 62, online resource Heidelberg University Library/Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/ulk1926/0062

[12] Only page-by-page searches of Ulk magazine can be performed in the Heidelberg historical inventory/Heidelberger historischen Beständen, https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/ulk, in this case Volumes 1925-1930, because a full-text search is not available. The images in the media library below only show a selection.

[13] All illustrations by Kirszenbaum in the magazines Gebrauchsgraphik and Der Querschnitt can be found in the web portal Illustrated Magazine of Classical Modernism/Illustrierte Magazine der Klassischen Moderne by using the terms “Kirschenbaum” and “Duwdiwani” in a full-text search, https://www.arthistoricum.net/themen/textquellen/illustrierte-magazine-der-klassischen-moderne/kollektion/suche/

[14] Der Querschnitt, Volume 6, Issue 7, Berlin, July 1926, page 526, online resource: https://www.arthistoricum.net/werkansicht/dlf/73192/48/?tx_dlf%5Bhighlight_word%5D=Kirschenbaum

[15] Der Querschnitt, Volume 7, Issue 3, Berlin, March 1927, page 194, online resource: https://www.arthistoricum.net/werkansicht/dlf/73193/56/?tx_dlf%5Bhighlight_word%5D=Kirschenbaum; page 201, online resource: https://www.arthistoricum.net/werkansicht/dlf/73193/67/?tx_dlf%5Bhighlight_word%5D=Kirschenbaum

[16] Der Querschnitt, Volume 11, Issue 3, Berlin, March 1931, page 163, online resource: https://www.arthistoricum.net/werkansicht/dlf/73271/31/?tx_dlf%5Bhighlight_word%5D=Kirschenbaum

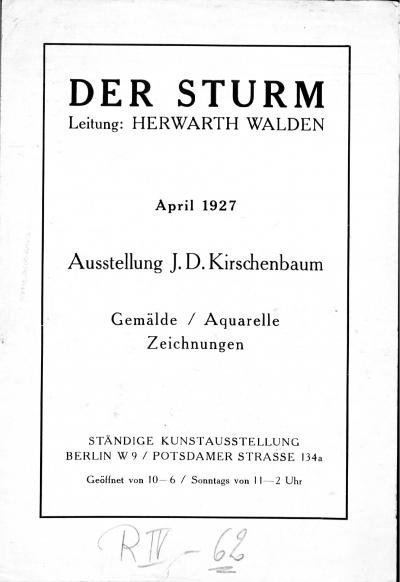

Kirszenbaum got to know the publisher of the magazine Der Sturm and manager of the Sturm Gallery, Herwarth Walden (1878-1941), probably through Paul Citroen. Citroen had already set up the art book shop for Walden in 1917 next to the gallery at Potsdamer Straße 134a and had gone to the Netherlands in the same year as a representative of the Sturm. In August 1917, Citroen published an expressionist essay about Marc Chagall in the Sturm magazine.[17] At any rate, in April 1927 Kirszenbaum was given an extensive exhibition in the Sturm gallery, in which he was able to show 71 charcoal, chalk, ink and watercolour drawings along with nine oil paintings and for which one of the customary small catalogues was produced, which included three images of his works (see PDF 1). Critics recognised a significant influence by Marc Chagall on Kirszenbaum’s works. Ernst Collin (1886-1942 murdered in Auschwitz), one of the editors of the left-wing liberal Berliner Volks‑Zeitung, which had close links to the DDP and appear under the Mosse Publishing House/Mosse Verlag, wrote in the feature column of the twice-daily paper on 30 April that the motifs of the drawings and watercolours revealed three things: “Firstly, that he is a Russian, secondly, a Jew and thirdly a disciple of his country man and fellow believer Marc Chagall. The soul of the Russian ghetto is in his prints. He does not get tired of telling tales of old bearded Jews who love the Talmud. In the nervous strokes of his drawings, in the colourful overtones in his watercolours, you can also see – in spite of all his attachment to Chagall – the independence of a considered stylistic expression.”[18]

Even if Kirszenbaum’s later works (Fig. 49) do show considerable influence by Chagall, the few works by the artist handed down from the period before the Second World War are not enough to confirm this. It certainly appears that because of their shared Hasidic heritage, Kirszenbaum felt a connection with Chagal, who Walden got to know in Paris in 1913 and who only lived in Berlin for a short time in 1922/23. Chagall portrayed rabbis, real people and scenes from the everyday life of the Eastern European Jews, as well as many other themes. In May 1917, four drawings by Chagall appeared in the Sturm magazine, the portrait of a rabbi and a street scene with a violin being astonishingly similar in terms of their subject matter to the later works of Kirszenbaum[19], the painting “Dispute” in the Sturm catalogue (see PDF 1) and the fiddler in the Querschnitt magazine (Fig. 14), but differing in style. However, the most famous model for Kirszenbaum’s motif of the rabbi sitting at the table in front of his scriptures has to be Chagall’s watercolour “One says” from 1921, which appeared in the Sturm magazine as a four-colour print [20] and which continued to be sold as an art print by Der Sturm publishing house right into the 1930s and advertised in the Sturm magazine.[21] The motif corresponded, with just a few differences, to the first version of Chagall’s painting “The Rabbi (The pinch of snuff)” created in 1912, the second version of which, produced in 1926, was bought by the Mannheim Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art/Kunsthalle Mannheim, then later confiscated by the Nazis, exhibited from 1937 in the Degenerate Art exhibition and finally purchased at auction in Lucerne in 1939 by the Basel Museum of Art/Kunstmuseum Basel.[22]

With a few exceptions, the titles of the works exhibited by Kirszenbaum in the Sturm gallery in 1927 indicate real people, everyday or religious themes that were known to the artist from Jewish life in Staszów, a small town with around nine thousand inhabitants at the time, more than half of the population being Jewish. It is possible that with this exhibition Herwarth Walden hoped to ride on the earlier successes he had enjoyed with Chagall, whose works he had shown in the Sturm gallery in June 1914[23]. During these years, Walden also followed the social developments in the Soviet Union with great interest, and had called on people to vote for the list of the KPD (Communist Party of Germany). He regularly published adverts for the Association of Friends of the New Russia/Gesellschaft der Freunde des Neuen Russland in the Sturm magazine and travelled to Moscow in 1927 on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution.[24] After returning from his travels, during which he also visited the Podolian town of Proskurov/Płoskirów (today Khmelnytsky/Chmelnyzkyj), he reported on the blessings of Bolshevism in the September issue of the Sturm.[25]

[17] Der Sturm, 8th Edition, 5th Issue, Berlin, August 1917, page 68, online resource: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/sturm1917_1918/0074/image

[18] E.C.: Kunstwanderung. […] Kirschenbaum, in: Berliner Volks‑Zeitung, 75th Edition, No. 202, 30 April 1927, page 2, morning edition, online resource http://zefys.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/index.php?id=dfg-viewer&set%5Bimage%5D=2&set%5Bzoom%5D=default&set%5Bdebug%5D=0&set%5Bdouble%5D=0&set%5Bmets%5D=http%3A%2F%2Fcontent.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de%2Fzefys%2FSNP27971740-19270430-1-0-0-0.xml. The authorship of Ernst Collin (see comment 7) is indisputable because he referred to the earlier critique in the 1931 exhibition catalogue authored by him in the Galerie Fritz Weber in Berlin.

[19] Der Sturm, 8th Edition, 2nd Issue, Berlin, May 1917, pages 21 and 25, more drawings by Chagall on pages 23 and 27, online resource: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/sturm1917_1918/0027/image

[20] Der Sturm, 12th Edition, 12th Issue, No. 1921, 19/02/1926, page 209, online resource https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/sturm1921/0261/image

[21] Advertisement for coloured prints by Mark Chagall: Interior / Barber’s Shop / The Holy Coachman / One Says (Jew) / Act / watercolour, Der Sturm, 13th Edition, 5th Issue, Berlin, May 1922, page 81, online resource https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/sturm1922/0105/image; 17th Edition, 12th Issue, Berlin, March 1927, back cover, online resource https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/sturm1926_1927/0246/image; 20th Edition, 8th Issue, Berlin August/September 1930, 4th cover page.

[22] Christoph Zuschlag: “… one of his strongest images”. The fate of the “Rabbi” by Marc Chagall, in: Uwe Fleckner (Publisher), The ostracised masterwork. The fate of modern art in the “Third Reich” = Schriften der Forschungsstelle Entartete Kunst, 4, Berlin 2009, pages 401-426

[23] Goudz 2012 (see Literature), page 535

[24] Georg Brühl: Herwarth Walden and “Der Sturm”, Leipzig, Cologne 1983, page 71, 77

[25] “ … this is not a country of destruction. The USSR is a country of development. A country of work. And a country longing for the happiness of its people.” Herwarth Walden: USSR 1927, in: Der Sturm, 18th Edition, 6th Issue, Berlin, September 1927, pages 73-75, online resource https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/sturm1927_1928/0082/image

This coincided with Walden’s enthusiastic support for artists from Eastern Europe. In contrast with his rejection of constructivism, he supported the Polish artist Henryk Berlewi (1894-1967) in 1924 by printing his manifesto “Mechano-Faktur”[26] and by giving him an exhibition in the Sturm gallery, as well as supporting the artists of the Warsaw Group Blok which he co-founded with Berlewi, Teresa Żarnowerówna (1897-1949) and Mieczysław Szczuka (1898-1927). When Szczuka was killed in an accident whilst hiking in the mountains in August 1927, Walden wrote an enthusiastic obituary in the Sturm.[27] The death of Szczuka meant that Kirszenbaum was a welcome addition to Walden’s fold of artists in April 1927, combining as he did his heritage from the part of Poland previously governed by Russia with the expressive motifs of Hasidic Judaism. In 1930 Kirszenbaum wrote in a letter to Paul Citroen that the art critic Max Osborn (1870-1946), editor of the people’s Vossische Zeitung, had described him as a “very strong painter” but had lamented the fact that he did not belong to the same cohort as Marc Chagall” or that he had not come on to the market before him.[28] In the exhibition catalogue of the Galerie Fritz Weber, which showed Kirszenbaum’s work from November 1931 in Derfflingerstraße 28 in the Tiergarten district, Collin again commented that the artist had “freed himself from his role model Chagall” in the last four years and had found a stylistic expression of his own.[29]

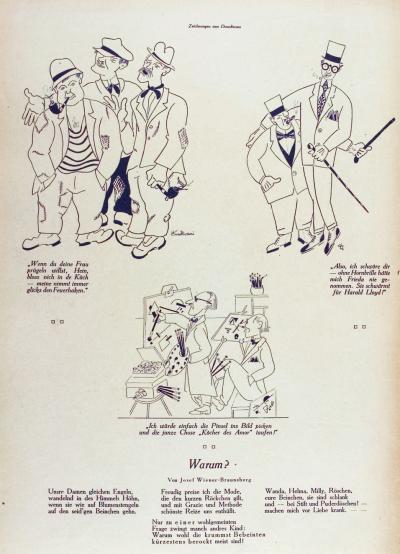

In 1929, Kirszenbaum was able to temporarily compensate for losing Ulk as a client by arousing the interest of the Munich magazine Jugend, a multifaceted popular paper published since 1896 as a weekly paper for art and life with numerous cartoons and reproductions of artworks. It is not known how this contact came about. However, from other cartoonists of the time we know that it was usual for artists to apply to different magazines or for them to find work with them through agents and authors, who worked for different publication media.[30] The first of Kirszenbaum’s drawings for Jugend, two men having a conspiratorial conversation, appeared under the pseudonym “J. Duwdiwani” in July 1929.[31] However, until July 1931 Kirszenbaum was only able to place seven of his drawings with the magazine (Fig. 32-34), most of them appearing in a compact format and on less interesting pages, with the editorial departments almost certainly devising the accompanying satirical text.[32] Cartoons, which Kirszenbaum would undoubtedly have been unable to publish in any of the aforementioned magazines, can be found in letters to Paul Citroen from 1932 and 1934 in the Bauhaus Archive collection in Berlin, including a cartoon of Hitler: “The handsome Adolf as an acrobat” and a drawing “Professor of ethnogeny in the Third Reich”.[33]

It is not clear whether Kirszenbaum stayed in contact with Herwarth Walden after his exhibition in the Sturm Gallery. However, he had at least one work on display at the November Group’s Ten Year anniversary exhibition in 1929 as part of the Juryfreien Kunstschau in the State Exhibition Building/Landes-Ausstellungsgebäude at the Lehrter train station in Berlin.[34] The November Group, an association with 120 to 170 members founded in 1918 as a tribute to the November Revolution, found its recruits predominantly amongst the artists of the Sturm circle.[35] At this time, if not even earlier, Kirszenbaum began to form close ties to radical left-wing groups. He became a member of the Association of Revolutionary Visual Artists of Germany/Assoziation revolutionärer bildender Künstler Deutschlands (ARBKD), Asso for short, which had been founded in March 1928 by young artists from groups within the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), the communist artists’ association Rote Gruppe formed around George Grosz, John Heartfield and Rudolf Schlichter and communist members of other artists’s associations modelled on the Artists’ Association of Revolutionary Russia/Assoziation der Künstler des revolutionären Russlands (AChRR). Kirszenbaum is also said to have become a member of the KPD.[36]

In 1930 he married Helma Joachim (1904-1944 murdered in Auschwitz), who worked as a secretary to the Guild of the German Stage/Genossenschaft Deutscher Bühnen-Angehöriger. The couple initially lived in Eichwalde near Berlin, before moving to Berlin-Adlershof at the beginning of 1932.[37] In July 1930 whilst still in Eichwalde, Kirszenbaum approached Paul Citroen in Amsterdam a number of times to ask whether he would be able to help get his works published in Jewish magazines or have them shown in an “arts exhibition in Amsterdam”, stating as his reason “that I was poor and still am”.[38] Presumably on the recommendation of Citroen, the art dealer Carel van Lier (1897-1945 in the Hannover-Mühlenberg subcamp) exhibited Kirszenbaum’s drawings in his gallery in Amsterdam in 1931.[39]

[26] Der Sturm, 15th Edition, 3rd Issue, Berlin, September 1924, pages 155-159, online resource https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/sturm1924/0173/image

[27] “The new art of Poland has lost its greatest representative.” Herwarth Walden: Mieczyslaw Szczuka, in: Der Sturm, 19th Edition, 1st Issue, Berlin, April 1928, page 185 f., followed by an “Architectural Project” of the Polish constructivists, page 187-193, online resource: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/sturm1928_1929/0007/image

[28] Letter from J.D. Kirszenbaum to Paul Citroën dated 21 October 1930, Bauhaus Archive 8034/120, quoted from Inna Goudz 2012 (see Literature), page 534

[29] Quoted from Goudz 2012 (see Literature), page 534

[30] As an example, in 1928 the Berlin author Reinhard Koester, who wrote under the pseudonym Karl Kinndt for the satirical magazines Ulk and Simplicissimus, found work for the Flensburg cartoonist Herbert Marxen with the Rudolf Mosse publishing house in Berlin and consequently with Ulk and with Jugend in Munich. (Axel Feuß: Herbert Marxen – A Life in Cartoon, in: Politically Incorrect. The Flensburg cartoonist Herbert Marxen (1900-1954), Exhibition Catalogue Museumsberg Flensburg, 2014, page 19)

[31] Jugend, 34th Edition, Munich 1929, No. 27, page 437, online resource http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/jugend1929/0440

[32] How editors handled the satirical drawings at their regular editorial meetings is well documented for Herbert Marxen (see comment 30, Feuß 2014, page 20 f.). All Kirszenbaum’s drawing in Jugend can be found by entering the search term “Duwdiwani” in the Heidelberger historical inventory – digital, https://www.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/helios/digi/digilit.html

[33] “The handsome Adolf as an acrobat”, letter to Paul Citroen from 2 January 1932, Inv. No. 8034/134; “Professor of ethnogeny in the Third Reich”, letter to Paul Citroen from 23 April 1934, Inv. No. 8034/161, both in the Bauhaus Archive, Berlin

[34] Involvement of artists and architects in exhibitions of the November Group 1919-1932. Version 1.3. As at: 2 April 2019, published by the Berlinische Galerie. State Museum of Modern Art, Photography and Architecture/Landesmuseum für Moderne Kunst, Fotografie und Architektur, Berlin, page 53, online: https://www.berlinischegalerie.de/fileadmin/content/bilder/sammlungen/kuenstlerarchive/findbuecher/beteiligung_von_k%C3%BCnstler_innen_u._architekt_innen_an_ausst.pdf. After this time, however, Kirszenbaum (Kirschenbaum) is not included on the two known lists of members of the November Gruppe from 1925 and 1930.

[35] Brühl 1983 (see comment 24), page 66-69

[36] Revolution and Realism 1978 (see Literature), page 49 f.

[37] History of Berlin’s Kirschenbaumstraße, https://berlin.kauperts.de/Strassen/Kirschenbaumstrasse-12524-Berlin. See also the testimony of Helma Kirschenbaum’s cousin, né Joachim, for Yad Vashem. Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority, https://yvng.yadvashem.org/index.html?language=de&s_lastName=Kirschenbaum&s_firstName=Helma&s_place=&s_dateOfBirth=, as well as the entry in the Book of Remembrance. Victims of Persecution …, https://www.bundesarchiv.de/gedenkbuch/de1089586

[38] Letter from J.D. Kirszenbaum to Paul Citroen from 5 July 1930, Bauhaus Archive 8034/122; Postcard from J.D. Kirszenbaum to Paul Citroen dated 31 July 1930, Bauhaus Archive 8034/119, quoted from Goudz 2012 (see Literature), page 533

[39] The Gallery Van Lier/Kunstzaal Van Lier, Rokin 126, in Amsterdam, specialised in realism, magical realism and expressionism. The Museum de Fundatie in Zwolle houses a drawing showing a portrait of Kirszenbaum produced by Paul Citroen in 1934, presumably in Paris, online: https://www.museumdefundatie.nl/nl/collectie/object/?pagina=77&id=1542&#menu

In October/November 1931, Kirszenbaum took part in the international exhibition in Berlin entitled Women in Need, which was held in the Haus der Juryfreien in the Platz der Republik and in which the artist showed a portrait of a lady painted in oil.[40] This was in response to a campaign against the abortion law (paragraph 218) in the women’s magazine Der Weg der Frau, which was published by the publishing group belonging to the communist publisher Willi Münzenberg (1889-1940). In 1932 and 1933, the magazine Magazin für Alle, which belonged to the Universum Bücherei für Alle book club, which had links to the KPD and was part of the International Workers’ Assistance/Internationalen Arbeiterhilfe (IAH) organised by Münzenberg, published graphic scenes by Kirszenbaum, including a community gathering in the synagogue to accompany an article by Nándor Pór entitled “God’s Law?“.[41] More of his drawings appeared in the satirical magazine Roter Pfeffer, successor to the Eulenspiegel in Münzenberg’s Neuen Deutschen Verlag, and in the Roten Fahne, the main publication of the KPD.[42]

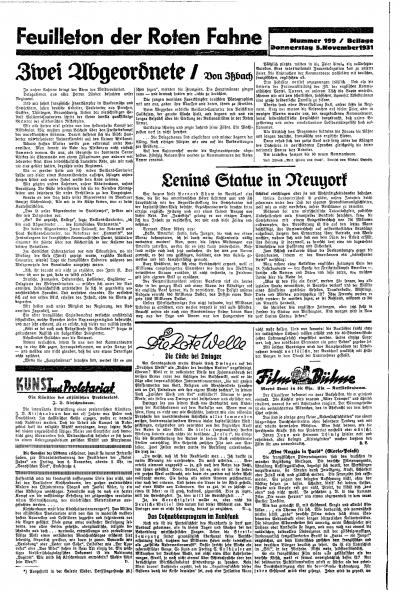

In November 1931, on the occasion of his exhibition in the Galerie Fritz Weber, Kirszenbaum was commended in the Roten Fahne by the paper’s culture editor Alfred Durus (Alfréd Kemény,1895-1945), member of the Sturm circle and co-founder of the Asso, as “an artist of the Eastern European proletariat” (see PDF 2). Ideologically, the artist finds himself “in a transitional stage between mysticism and marxism”. The milieu of the Eastern Jewish proletariat “is suggestively and fascinatingly brought to life by him in artistically masterful oil paintings and watercolours”. “However, one hopes this ideological ascension will not be overturned like it was for the great proletariat painters of Eastern European Judaism, Chagall and Jankel Adler”. “At any rate, a hard battle still has to be fought to ensure complete coverage of the contemporary revolutionary world view, dialectic materialism”.[43]

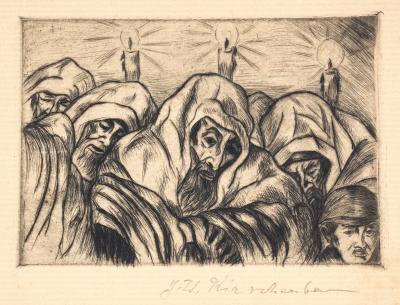

In 1932, Kirszenbaum showed his works at the Revolutionäre Malerei exhibition, a special exhibition of the Association of Revolutionary Visual Artists/Bund revolutionärer bildender Künstler (BRBKD) now referred to as Asso.[454] The exhibition showed works of artists, and indeed of members of the BRBKD, whose work had previously been removed from the Great Berlin Art Exhibition/Großen Berliner Kunstausstellung by the police because of its critical content. In Magazin für Alle, Durus reported on Kirszenbaum’s participation in the exhibition, as well as that of Asso members Alois Erbach (1888-1972) and Horst Strempel (1904-1975) and described Kirszenbaum’s etching “Pogrom” (Fig. 11): Kirszenbaum’s scenes from Eastern European Judaism, “do not show the life of a religious community but rather the terrible fate of an Eastern proletariat that has much in common with the fate of all the word’s proletarians.”[45]

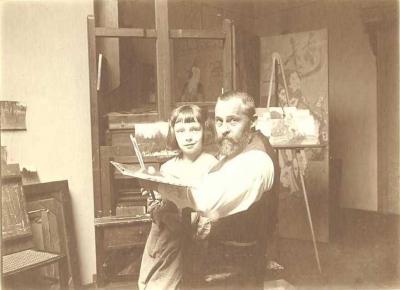

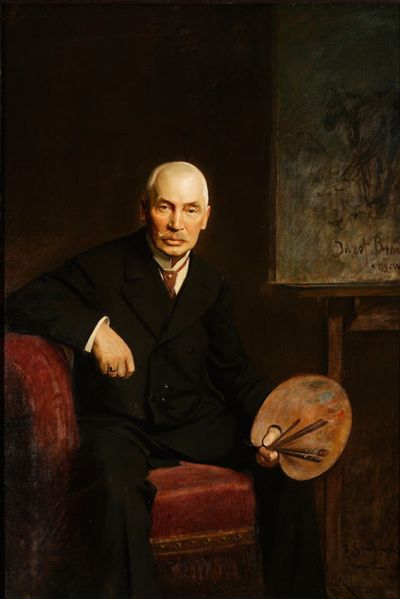

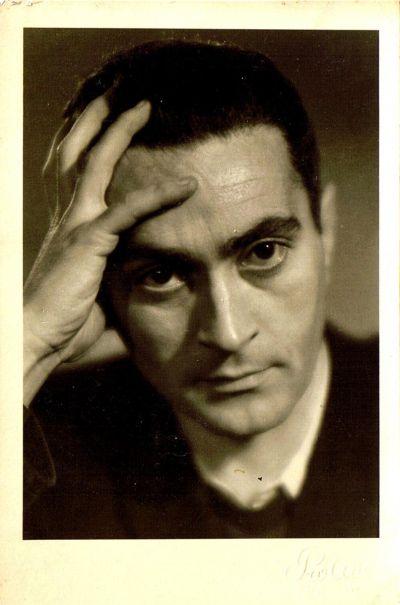

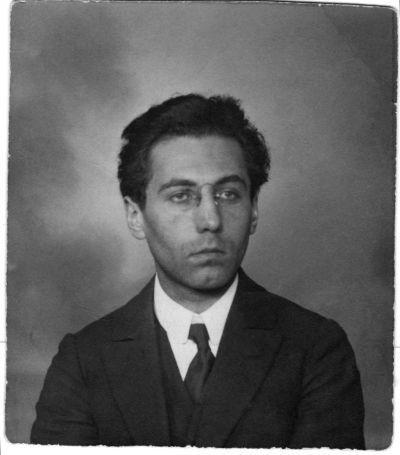

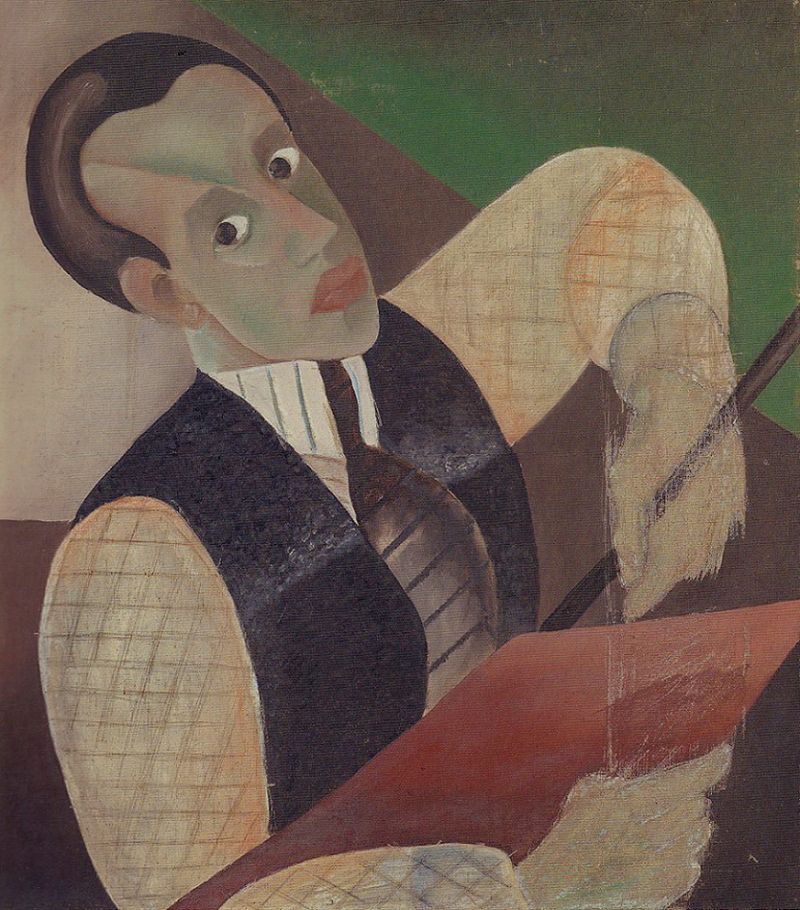

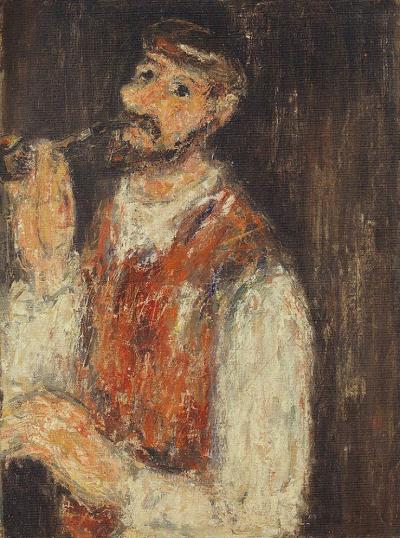

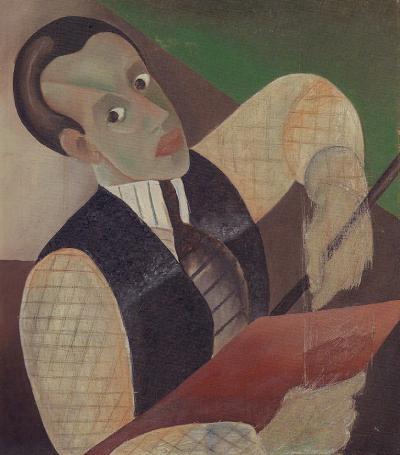

Artistically, Kirszenbaum had favoured different styles since his time at the Bauhaus. The two earliest known works, etchings with scenes from the synagogue, “Ba'ei Shalom” (those who come in peace) and a boy before the Rabbi with the Tora,[46] were presumably produced in 1923 at the Bauhaus in Weimar and still demonstrate the artist’s autodidactic, naturalistic style. The self-portrait created ca. 1925 (see cover photo) reveals a cubist influence. The voluminous and rounded forms of the upper body and the arms appear doll like and make reference to the few self-portraits by Oskar Schlemmer, the “Male Head I” from 1912.[47] Even the sharp nose, the almond eyes, the sleek hairstyle and the ears that seem to be stuck on appear to have their origins there. However, similarities with the nose and eye section in the self-portrait created by Chagall in 1914 can also be found.[48] As the head of the mural workshop at the Bauhaus, Schlemmer was obviously well known to Kirszenbaum. The “Triadic Ballet” made up of cubist figurines was performed during the Bauhaus Week at the Weimar National Theatre in August 1923, with exhibitions and publications referring to it even years later. Kirszenbaum, possibly during his time in Berlin, portrayed himself with his waistcoat, stand-up collar and tie as an attractive young man from metropolitan society and with his professional attributes, his palette and his brush.

[40] Revolution and Realism 1978 (see Literature), page 50

[41] Magazin für Alle, Volume 7, No. 4, Berlin 1932, depicted in the Revolution and Realismus exhibition catalogue 1978 (see Literature), page 130, Fig. 438, caption page 269

[42] Linsler 2013 (see Literature), page 293 f.

[43] D. (Alfred Durus): An artist of the Eastern Jewish proletariat. J.D. Kirschenbaum, in: Die Rote Fahne, No. 199, Berlin, 5 November 1931, page 10, online resource: http://zefys.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/index.php?id=dfg-viewer&set%5Bimage%5D=10&set%5Bzoom%5D=default&set%5Bdebug%5D=0&set%5Bdouble%5D=0&set%5Bmets%5D=http%3A%2F%2Fcontent.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de%2Fzefys%2FSNP24352111-19311105-0-0-0-0.xml

[44] Revolution and Realism 1978 (see Literature), page 50

[45] Alfred Durus: Revolutionary painting. Images from Erbach, Kirschenbaum, Strempel and Wegener, in: Magazin für Alle, Volume 7, No. 8, Berlin, August 1932, page 42. The Berlin exhibition Revolution and Realism 1978 (see Literature) showed Kirszenbaum’s etching “Pogrom”, forgotten at that time, after the illustration in the essay by Alfred Durus (catalogue page 269).

[46] Both works are owned by the Leo Baeck Institute in New York, https://www.lbi.org/artcatalog/search?q=Kirszenbaum. In reality, the titles given there, “Paul von Jecheskiel”, describe the original change of ownership (i.e. presented by Jecheskiel to Paul). What is supposedly a “W” in the signature is in reality a “D”, the flourish at the top right going to the right instead of to the left. Kirszenbaum later corrected this anomaly. It can be assumed that both etchings were produced during Kirszenbaum’s early days at the Bauhaus because professional machines were to print them.

[47] Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, https://www.staatsgalerie.de/g/sammlung/sammlung-digital/einzelansicht/sgs/werk/einzelansicht/2B9BA3E84A5ADB144EECE19798B4A3CB.html

[48] Basel Museum of Art/Kunstmuseum Basel, http://sammlungonline.kunstmuseumbasel.ch/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=15501&viewType=detailView

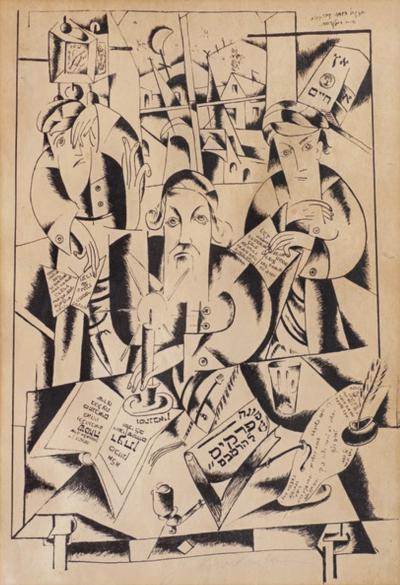

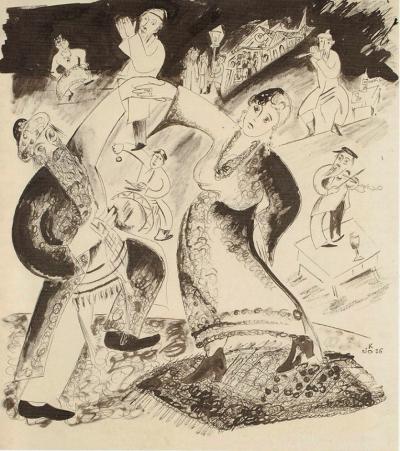

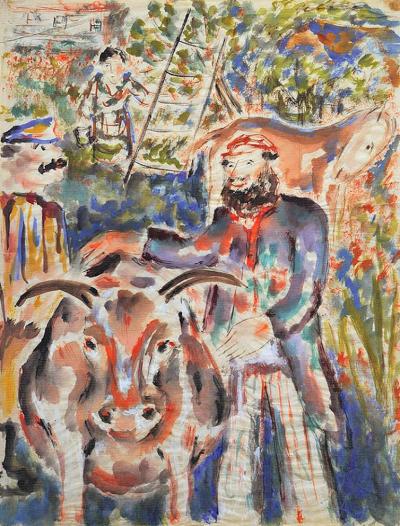

“Studying the Maïmonide” (Fig. 2) and “Musicians and their disciples” (Fig. 3), two ink drawings produced in Berlin in 1925 directly after Kirszenbaum’s studies at the Bauhaus, reflect, with their two-dimensional style, overlapping geometric and prismatic shapes and the introduction of written elements, art movements of the time between cubism, Dadaism and expressionism. It is possible that they were intended as templates for woodcuts and linocuts, like the high-contrast monochrome ones created by a number of artists at this time as illustrations and graphic supplements for magazines, such as the Sturm. The motifs reflect everyday scenes from the shtetl, which Kirszenbaum had experienced in his youth and childhood in Staszów and which he described in his written memoirs: studying the old Jewish scriptures in the Cheder, and the traditional fiddlers whose music brought together townsfolk and animals alike, recalling similar motifs by Chagall.

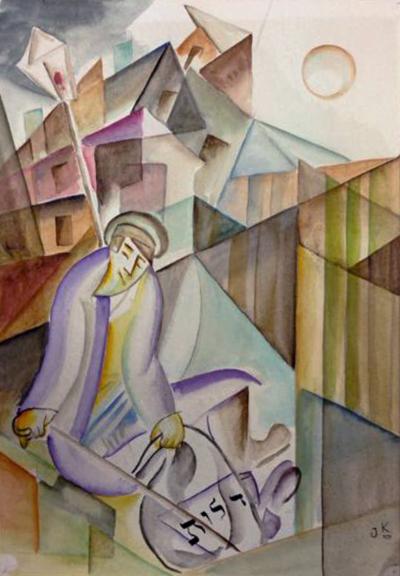

The geometric segmenting of the figures and the schematised physiognomies of the “musicians” (Fig. 3) recall the early work of Chagall, such as his “The cattle dealer” from 1912: sold by the Sturm publishing house as an art postcard and still depicted by Walden in a written defence of expressionism as late as April 1926.[49] In the “Maïmonide” work (Fig. 2), a prismatically blended cityscape, like the one created in 1922 in “Mellingen VI” by Lyonel Feininger, head of the printing workshops at the Bauhaus, appears in the view through the back window.[50] Kirszenbaum’s watercolour “Sorrow”, painted around 1925, is reminiscent of Feininger, but also of the prismatic shapes of the “Monument to the March Dead” in the main cemetery in Weimar created in 1922 by Walter Gropius, the director of the Bauhaus (Fig. 4). The painting “Fiddler in the shtetl” (Fig. 5), prepared in the cubist style as a motif in Chagall’s early work,[51] but also described in Kirszenbaum’s written memories of childhood,[52] sets the tone for his late-impressionist style of the thirties and forties (Fig. 38, 42).

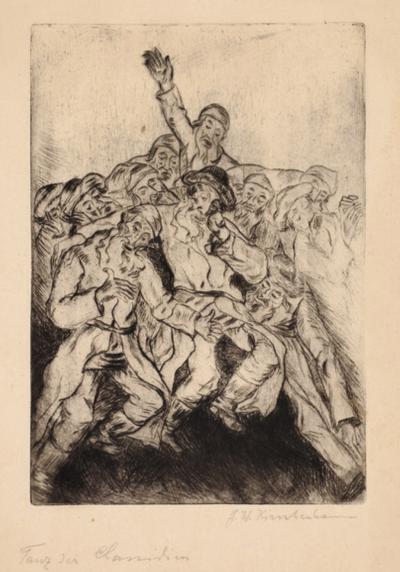

A drawing and etchings with scenes from Jewish life (Fig. 6-11), which follow the two earliest known motifs of this kind from 1923, are very different in character. With its scattered little figures, “The Wedding” (1925, Fig. 6), an ink drawing owned by the Jewish Historical Institute/Jüdischen Historischen Instituts in Warsaw, follows the stylised, light-hearted style favoured by Chagall in his etchings around 1925[53] which became characteristic of his later work. The sharp-edged expressionist scenes with faces of praying Jews visibly moved (Fig. 7-9) recall similar heads and similar scenes by Ludwig Meidner (1884-1966) and Jakob Steinhardt (1887-1968), who both belonged to the group of Berlin Sturm artists and who are both known for their Jewish motifs. The influence of these two artists is particularly visible in Kirszenbaum’s motional scenes, “Dance of the Hassidim“, (1925, Fig. 10) and “Pogrom by the Cossacks” (ca. 1930, Fig. 11).

Also known for his Jewish motifs was the painter Issachar Ber Ryback (1897-1935). Originally from the Ukraine but living in Berlin from 1921, he belonged to the November Group, showed his works in the Juryfreie Kunstaustellung and went to Paris in 1926. He also produced numerous versions of a fiddler in the shtetl and other traditional folk scenes. It is fair to assume that during his time in Berlin, Kirszenbaum moved increasingly within the circle of Jewish artists, including Paul Citroen, where he was able to make a name for himself with the scenes he produced. Also documented is Kirszenbaum’s friendship with the Jewish painter Felix Nussbaum (1904-1944 murdered in Auschwitz), who studied at the Lewin-Funcke-Schule in Berlin from 1923, was ranked amongst the successful young Berlin artists from 1930/31, and in 1933 emigrated via Italy and France to Belgium.[54] In 1931, Nussbaum took part in the Women in Need/Frauen in Not exhibition.[55]

[49] Herwarth Walden: Expressionism, in: Der Sturm, 17th Edition, 1st Issue, Berlin, April 1926, pages 2-12, Marc Chagall: The Cattle Dealer, page 5, https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/sturm1926_1927/0013/image. Today, the painting can be found in the Basel Museum of Art/Kunstmuseum Basel, http://sammlungonline.kunstmuseumbasel.ch/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=1129&viewType=detailView

[50] Depicted in the catalogue accompanying the Bauhaus Exhibition of 1923: State Bauhaus Weimar 1919-1923, Weimar, Munich, 1923, page 183. Today the painting can be found in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, https://www.imj.org.il/en/collections/387956

[51] Marc Chagall: “The Violinist”, 1912/13, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, https://www.stedelijk.nl/en/collection/753-marc-chagall-le-violoniste; a wood or lino cut by Chagall with a violin in front of the shtetl depicted in 1917 in: Der Sturm, 8th Edition, 2nd Issue, Berlin, May 1917, page 25, online resource https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/sturm1917_1918/0031/image

[52] “The blind violinist would come to Staszów each year right before Pesach; he was the herald of spring in Staszów. The piercing strings of his violin would express boundless sadness, and when he would accompany his playing with a song on the pogrom in Kishinev, the whole picture of the terrifying events would be visible before my eyes.” (J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013, see Literature, page 129)

[53] Marc Chagall: Acrobat with the violin, 1924, etching and drypoint; illustrations for Nikolai Gogol, Dead Souls, 1923-27, etchings (Marc Chagall. Graphic print, published by Ernst-Gerhard Güse, Stuttgart 1985, page 247, 46-73)

[54] Around the turn of 1946/47, Kirszenbaum enquired about the fate of Felix Nussbaum in a letter to the Director of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, Paul Fieren, and on 20 January 1947 received the response that Nussbaum and his wife had been deported to a concentration camp and had not returned. (Letter pictured in J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013, see Literature, page 26 f.)

[55] Adolf Behne: The “Women in Need” exhibition, in: Welt am Abend, No. 243, 1931; depicted in: Revolution and Realism 1978 (see Literature), page 28

This stylised, light-hearted style is also evident in the satirical drawings, which were presumably produced in 1925/26 but which appeared in Der Querschnitt in later years (Fig. 12-14) and included another obviously blind fiddler in the shtetl clashing with a passer-by. Kirszenbaum began producing cartoons for Ulk in spring 1926, initially with somewhat simple contours (Fig. 15-16, 19) but by July they had already evolved into large-format, elegant but acerbic social scenes defined by strong monochrome contrasts (Fig. 17, 18, 20-31). Well-known cartoonists, like Eduard Thöny, Thomas Theodor Heine, Olaf Gulbransson and Karl Arnold, who worked for the magazines Simplicissimus and Jugend from the end of the 19th century, were still active in the 1920s and 1930s, and were joined by young illustrators, such as Herbert Marxen.

Kirszenbaum gave this long-established style a new note by taking the scenery and physiognomies favoured by George Grosz as his guide. Since the appearance of his portfolio “The face of the ruling class” (1921) as well as in his painting “Pillars of society” produced in 1926 (Berlin National Gallery/Nationalgalerie Berlin), Grosz had systematically worked his way through the institutions of the Weimar Republic, politicians, the Christian churches and the conservative bourgeoisie lampooning the petty bourgeois, double standards, militarism and moral decline. Since 1926, Grosz had also worked for Simplicissimus, the Eulenspiegel and later for the Roten Pfeffer. The victims of Kirszenbaum’s graphic exaggerations and ridicule were the conservative bourgeoisie loyal to the Kaiser (Fig. 17), German Nationalist fraternities and politicians (Fig. 20, 25, 30 top), managers and fat cats (Fig. 21), ponderous family men (Fig. 22) and spare-time politicians (Fig. 26) as well as the high society (Fig. 29) or so-called “modern” artists (Fig. 30 bottom). Thanks to his talent for illustration, these characters would also have been recognisable without the literary satire and witticisms added by the editorial department.

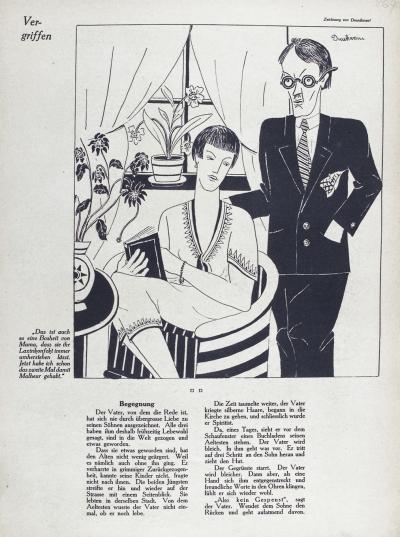

He also drew more benign social scenes that accurately characterised the dress and standard of living in the “Golden Twenties” (Fig. 18, 23, 24, 27, 28). The style of these works leans on that of the New Objectivity/Neuen Sachlichkeit, as represented by Rudolf Schlichter, Otto Dix and others, whose critically caricaturing undertone influenced Kirszenbaum. He enjoyed particular success with his three-quarter page cartoon “The Expressionists’ Ball” (Fig. 31), in which he combined all the aforementioned styles with the written interjections of Dada and the prismatically blended composition lines of expressionism. With this combination, he created a comprehensive picture of the culture and customs of the time. From the beginning of the 1920s, artists balls, hosted by the academies and art schools or by free artists’ associations, were considered the annual highlight of social and cultural life, not just in Berlin. The cartoons for Jugend became more benign again (Fig. 32-34). However, in the two drawings published in the Querschnitt in 1931, the artist found himself focusing on male figures again, which Grosz and Dix had modelled before him (Fig. 35, 36).

In 1933, Kirszenbaum and his wife fled from the National Socialists to Paris when they found themselves in great danger, not just because of their Jewish heritage but also because of their close contact to the communists. They left all their possessions behind in Berlin, including nearly all of the artist’s works. Kirszenbaum appears to have settled in quickly. In November 1933, he took part in the Paris Autumn Salon, the Salon d’Automne, which started in 1903[56] and which had been dominated since the 1920s by painters from the Montparnasse artists’ quarter, including Chagall, Modigliani and Braque. It was considered the most important exhibition venue of the Avantgarde. Kirszenbaum exhibited there until 1935.[57] In November 1933, he also showed landscape paintings at an exhibition organised for the benefit of displaced artists from Germany by the French committee for the protection of Jewish intellectuals.[58]

[56] L'Écho de Paris of 3 November 1933, page 5, 5th column, first paragraph, online resource: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k8149828/f5.item. In the beginning, the artist obviously used a French spelling of his name “Kirchenbaum”, then later the German spelling before finally returning to the Polish spelling.

[57] Letter from Kirszenbaum to the Director-General of the French National Contemporary Art Collection/Fond National d’Art Contemporain in Paris dated 20 April 1945, pictured in: J.D. Kirszenbaum 1913 (see Literature), page 24 f.

[58] The persecuted intellectual Jews. Notices, in: Le Temps dated 1 November 1933, page 4, 2nd column, online resource: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k2493917/f4.item; also “Kirchenbaum” there

In January 1936, Kirszenbaum put on a one-man exhibition in the Galerie Mouradian-Vallotton in the Rue de Seine 41 with drawings and watercolours, which the Paris Journal Juif reported as being “in a cheerful palette between deep red and blue ... mainly dealing with Russian peasant life”.[59] During these years, the gallery handled works from the likes of Degas, Utrillo and Max Ernst. The conservative daily newspaper Paris-Midi announced Kirszenbaum’s exhibition as “Jewish painting” showing street and village scenes, poor merchants, farmers and workers. It went on to say that as far as the twenty watercolours were concerned, “the colours became more brilliant the more naively they were applied”.[60]

In 1938, the artist took part in the salon of the Association Artistique des Surindépendants, which was founded in 1929 and which mainly showed the works of surrealist and abstract painters. In 1938, he also exhibited works in the Exhibition of German Painters of the Free Artists’ Association/Exposition des Peintres Allemands of the Freien Künstlerbunds (FKB, Union of Free Artists/Union des Artistes Libres). Founded in Paris the previous year by German artists in exile, the association’s members included Max Ernst, Otto Freundlich and Hans Hartung as well as those artists primarily whose works had been removed from museums by the Nazis during the “Degenerate Art” campaign, or sold, destroyed, or defamed in an exhibition bearing the same name.

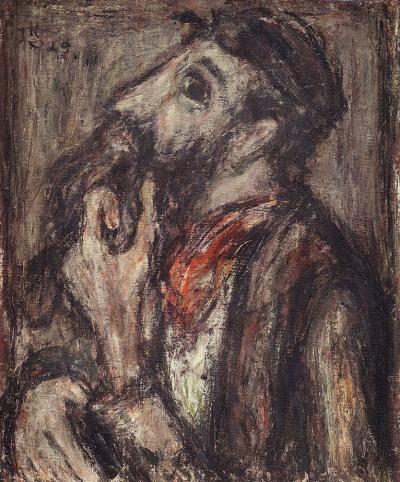

It is presumed that the “Man with cigarette” (Fig. 37), dating from the previous year, was one of the works shown at Mouradian-Vallotton. The work was one of those described in the press as watercolour street scenes with simple people in succinct contrasts of red and blue. A harmonica player and a double bass player,[61] a man with patched clothes, boots and a sack on his back[62] as well as two peasants in conversation in front of a horse and cart are also known to display this technique. He also produced paintings of an “Old Jew” with stick, cap and shoulder bag (1936),[63] an “Old Jew in Snowy Landscape” (ca. 1937)[64], the bust of a Jew[65] and “The Fisherman” (both 1938)[66] in muted brown and grey tones, reminiscent of the style of Braque and even of Rouault. Just like his earlier work in Berlin, the Jewish scenes and portraits are undoubtedly painted from memory and evoke people and events from Staszów. A “Sleepwalker” walking across the roofs of the town with a laughing moon in the sky, painted in an impressionist style around 1937 in light blue tones,[67] seems to have been influenced by Chagall or the surrealists.

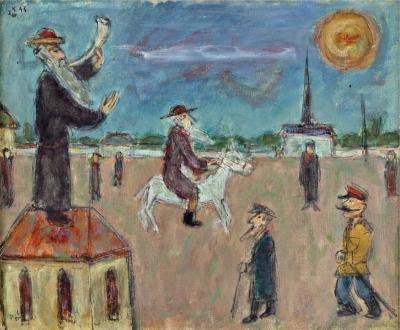

In a series of paintings, the artist transferred the biblical tradition to the town of his childhood: The painting “Jewish villagers greet the Messiah” (Fig. 38), produced in 1937, shows the Saviour in the form of a Hasidim as he rides into Staszów on a white donkey. On the saddle hangs a crown cap with the Teffilin and an embroidered bag containing the 613 commandments, the mitzwot. Visible at the edge of the picture on the left are the sign for Staszów station and the stationmaster; waiting for him on the right are Hasidic rabbis and prayer leaders and several groups of townsfolk who welcome the Messiah with signs displaying Hebrew script. In 1939, Kirszenbaum painted a new version of this theme (Fig. 39), and in 1942 and 1946 two more interpretations (Fig. 43, 47). Stylistically, he alternated between a late-impressionist concept showing the artist as a master of grey tones, and a seemingly naive and colourful character setting which could have been modelled on the works of the Fauves group of artists. However, the much publicised painting by James Ensor, “Christ's Entry into Brussels” (1888),[68] that was exhibited in Paris in 1939, may have been a catalyst for the theme, and also for the figures looking into the scene from the edges of the picture and the script tablets carried aloft.

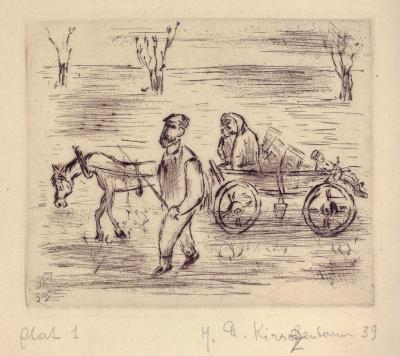

Around the same time, Kirszenbaum tackled another classic Jewish theme, the Exodus and the legend of the wandering Jew told since the middles ages, which had both achieved renewed currency due to the persecution of the Jews by the National Socialists and the resulting refugee movements. An oil sketch from 1938 in the collection of the Israel Museum in Jerusalem shows “Wandering Jews” sitting on their luggage in the open countryside.[69] In 1939, the artist created a series of etchings entitled “Exodus”. The series shows various lines of Jews escorted by soldiers (Fig. 41), a mother embracing her children,[70] and a family setting off with an open horse-drawn cart and a few belongings (Fig. 40). The artist also continued to pursue this theme after the end of the Second World War (Fig. 44).

[59] Exhibition of J.-D. Kirschenbaum, in: Le Journal Juif, 13th Edition, No. 3, 17 January 1936, page 4, 4th column, online resource https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k62282932/f4.image.r=Kirchenbaum. Kirszenbaum mentions the gallery in his letter of 20 April 1945 (see Comment 56).

[60] G.-J. Gros: Painters with feeling, in: Paris-Midi dated 24 January 1936, page 2, 2nd column, online resource: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k4729237j/f2.image.r=Kirchenbaum

[61] J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see Literature), page 140 f., https://www.kirszenbaum.com/france?lightbox=imagevuo

[62] ibid., page 89

[63] ibid., page 72

[64] ibid., page 71, https://www.kirszenbaum.com/early-period?lightbox=image5jn

[65] ibid., page 73

[66] ibid., page 149

[67] ibid., page 67

[68] The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/811/james-ensor-christ%27s-entry-into-brussels-in-1889-belgian-1888/

[69] J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see Literature), page 88

[70] ibid., page 93

From 1933 to the beginning of the Second World War, Kirszenbaum was an active member of the École de Paris, a fact evidenced by the few works and pieces of information preserved from these years. The term École de Paris does not describe a consistent art style or a closed group of artists, but rather all the French artists, but mostly the foreign artists, who shaped contemporary art coming out Paris from the turn of the 20th century. The French artists, such as Derain, Matisse, Braque, Rouault or Léger, who had settled in the Montparnasse district, were joined in several waves of immigrants by artists from Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, Germany and South America, but in larger number by artists from the Eastern European countries, such as Russia, Poland, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Romania and Hungary, who formed a vibrant artists’ quarter on the Montparnasse with its countless ateliers and cafes.

Only in more recent times has reference been made again to the fact that a large proportion of the foreign artists were of Jewish descent. They included at different times Henryk Berlewi, Marc Chagall, Henri Epstein, Otto Freundlich, Moise Kisling, Moise Kogan, Roman Kramsztyk, Rudolf Levy, Jacques Lipchitz, Louis Marcoussis, Amedeo Modigliani, Mela Muter, Jules Pascin, Issachar Ryback, Lasar Segall, Chaim Soutine, Marek Szwarc, Ossip Zadkine and many others. It is assumed that there were about five hundred artists who found their way from their native countries to Paris in the interwar years because of anti-semitic persecution and difficult personal or political circumstances, with 180 of those achieving greater importance.[71] After Hitler seized power, the Bauhaus student Moses Bagel, who was born in Vilnius, and the artists Jankel Adler and Kirszenbaum, who originated from Poland, as well as the painter Jacob Markiel, who came from Łódź, all fled from Germany to Paris. According to Claude Lanzmann, of the known artists, seventy one, that’s forty percent, died in the gas chambers of the German concentration camps located on Polish soil.[72]

Only a few of these artists devoted themselves to distinctly Jewish themes: Chagall, Kirszenbaum, Ryback, Arthur/Artur Kolnik who hailed from Stanisławów, and Emmanuel Mané-Katz born in the Ukraine. Kirszenbaum, who spent a lot of time in the museums and galleries of Paris studying both the older French masters and the modern ones and who is said to have been friends with Georges Rouault,[73] produced around six hundred paintings in the period from 1933 up to the start of the Second World War. They were confiscated from his apartment and destroyed by the Germans following their invasion of Paris.[74] This was the second time that the artist had lost all the work he had produced to that point.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Kirszenbaum and his wife were interned and separated from one another. He was detained in the Meslay-du-Maine camp east of Rennes, in which two thousand German and Austrian civilians from the Paris region were interned from September 1939 to June 1940 and which had been evacuated when the Germans advanced. He was then moved to a labour camp for foreign nationals in the village of Saint-Souveur near Bellac in the Haute-Vienne departement. Evidently, he was able to escape from there in 1942 and went into hiding until the end of the war.[75] Until June 1940, Helma Kirszenbaum was imprisoned in the Camp de Gurs internment camp in the South of France not far from the Spanish border. She was later released but stayed in Gurs to wait for her husband.[76] She presumably returned to Paris again later. At the end of 1943, she was arrested and taken to the Drancy collection and transit camp twenty kilometres north-east of Paris, from where 65,000 predominantly French Jews were sent to extermination camps. From there she was deported on 20 January 1944 to the Auschwitz concentration camp and murdered.[77]

Kirszenbaum continued to produce artistic work during his time in the camp and underground. In winter 1939, he produced a late-impressionist “Landscape with church”, which was predominantly painted in grey tones and which today is in the Israel Museum.[78] In 1940 he produced the view of a farmstead in spring.[79] Using a similar technique in Bellac in 1941, he painted a wood collector in a winter landscape who he may actually have seen there and is presumably not drawn from his recollections of Staszów.[80] With its concentration on colour and its serial abstraction, a series of still lifes with bouquets of flowers in bellied vases seems to have been influenced by the Fauves, perhaps by Vlaminck.[81] In 1942, recollections of Staszów were produced: a “Jew on a wintry street”[82], a “Staszów water carrier” (Fig. 42) and the painting “The Messiah and the angels arrive at the village” (Fig. 43), which again transfers the Christian theme of “Jesus entering Jerusalem” or Ensor’s Adaption to Jewish life. The painter paints himself in the picture (bottom left) as he records the scene with brush, palette and easel. The last three paintings show a late-impressionist painting style in grey and brown tones and are presumably just the few remaining examples of a much more extensive work that has been lost.

[71] Nieszawer 2015 (see Literature), page 397. Research carried out by Nadine Nieszawer, who points out that the Jewish origin of the largely internationally renowned artists has hardly been mentioned up to this point, is based on the early works of Chil Aronson: Images and faces of Montparnasse/Bilder und geshtaltn fun Monparnas/Scènes et visages de Montparnasse. Foreword by Marc Chagall, Paris 1963, and Hersh Fenster: Undzere farpaynikte kinstler. Foreword by Marc Chagall, Paris 1951

[72] Claude Lanzmann: Foreword, in: Nieszawer 2015 (see Literature), page 396

[73] J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see Literature), page 59, 66

[74] Letter dated 20 April 1945 (see comment 57)

[75] ibid.

[76] Letter from Helma Kirszenbaum to her husband dated 1 July 1940 from Gurs; Postcard from Jesekiel Kirszenbaum to his wife dated 26 July 1940 from Saint-Sauveur near Bellac, exhibited in the Jesekiel Kirszenbaum 2019 exhibition in the Centre for Persecuted Arts/Zentrum für verfolgte Künste in Solingen; see the report in this portal, https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/atlas-der-erinnerungsorte/jesekiel-kirszenbaum-ausstellung-solingen, Fig. 8; the postcard depicted in J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see Literature), page 78

[77] Central database of the names of the victims of the Holocaust, https://yvng.yadvashem.org/nameDetails.html?language=de&itemId=11562929&ind=0

[78] Landscape in winter with church, 1939, Israel Museum, Jerusalem, https://www.imj.org.il/en/collections/193211

[79] See the Solinger exhibition in this portal, https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/atlas-der-erinnerungsorte/jesekiel-kirszenbaum-ausstellung-solingen, Fig. 25

[80] J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see Literature), page 34, https://www.kirszenbaum.com/early-period?lightbox=imagebsv

[81] ibid., page 58, 61

[82] ibid., page 72

Kirszenbaum, now in the Rue Bobillot in Paris again not far from the Montparnasse artists’ quarter, experienced the end of the war and the period following it in utter desperation without news of his wife’s whereabouts.[83] “I have been living in pain and bitterness ever since. I am not a saint, I don’t have any faith in humans or in my own life”, he is later quoted as saying.[84] Artistically, he remained faithful to his previous themes initially. A series of paintings he produced again deals with the Exodus, i.e. with the flight and expulsion of the Jews. This series includes the expressive image “Exodus of a mother with two children “ (Fig. 44), the painting “My tears become a river”[85] with the portrait of an old man weeping in the foreground and fleeing and resting Jews behind him (both from 1945), as well as a picture with “Refugees”[86] huddling together in a boat on the open sea (undated, Tel Aviv Museum of Art). Several figure paintings again evoke his recollections of Staszów, including a “Blind fiddler”, a “Seated pedlar”, a “Jewish man with Tallit”[87] and a “Man from Staszów” painted in expressive contours (Fig. 45), as well as the impressionist “Portrait of Jew with pipe” which is sketched in a more or less cubist style (Fig. 46). In 1946 he produced a final version of the “The arrival of the Messiah in the shtetl” (Fig. 47) with some caricatures and some grotesquely positioned colourful figures.

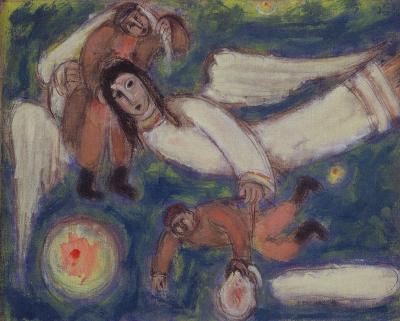

The bust of Christ on the cross (1944) and an ink drawing with the Hebrew inscription “God, why have you forsaken us”[88] were followed by more biblical themes: the portrait of a weeping Jewish man that can also be interpreted as Jesus with the crown of thorns, and an image of the despairing Job as a three-quarter figure.[89] Even the picture “My tears become a river” can refer to a passage from the Bible, the lament of the captives at Babel[90]. Individual portraits of apostles, saints, meditators, thinkers[91] and rabbis (Fig. 48) are accompanied by some of the artist’s sculptural works, including a “Jeremiah” as a teracotta figure[92]. The highlight of this series is the life-size triptych painted in 1947 (Tel Aviv Museum of Art),[93] of the prophets Moses, Jeremiah and Elias whose cubistically simplified contours in muted red and blue tones are possibly influenced by Rouault. By contrast, a series of paintings in which flying angels carry the lost souls out of the shtetl,[94] one of which is entitled “There is no room for Jews in our world”, are reminiscent of Chagall (Fig. 49).

The broad spectrum of the artist’s stylistic abilities is demonstrated in two contemplative portraits produced in 1946: the self-portrait (Fig. 50) painted in a late-impressionist style and the portrait of the young journalist Robert Giraud (1921-1997, Fig. 51), which is reminiscent in its style of the portraits painted by Modigliani, who died in 1920. Giraud hailed from Limoges, was imprisoned there by the Germans as a member of the Résistance and lived in Paris from the end of the war onwards. In 1945, Kirszenbaum had an exhibition in the Galerie Folklore, twenty kilometres south of Bellac. However, it is not known where the two met.

In 1946 Kirszenbaum’s palette became noticeably more colourful (Fig. 47, 49) and he began to tackle new themes. A “Harlequin”,[95] a “Trumpeter”[96] and a “Violinist” in gala dress refer to the world of the circus, a theme that was often favoured by the painters of the École de Paris, especially Rouault. The two-dimensional, vibrant colourfulness of these figure paintings alludes to the group of the Fauves, perhaps to Derain. Another visual recollection of Staszów, the watercolour “The butcher” (Fig. 52), owned by the National centre for the fine arts/Centre national des arts plastiques[97] in Paris, is also reminiscent of the Fauves with its splotches of colour.

During this period, Kirszenbaum managed to resurrect old contacts and form new ones. In 1946, he took part in the Salon des Tuileries and in the exhibition of the Salon de Mai group of artists, which was formed in opposition to the National Socialists in 1943 during the German occupation of Paris. In the same year, and again in 1952, the French National collection of contemporary art/Fond national d’art contemporain acquired works by Kirszenbaum that can be found today in the National centre for the fine arts/Centre national des arts plastiques. In 1947, he exhibited in the Galerie des Quatre chemins and in the salon of the group of artists called Les Surindépendants, of which he became a member the following year. But above all he was supported by Baroness Alix de Rothschild, who helped numerous artists in the post-war years to get back on their feet artistically. She took painting and drawing lessons with him, received him as a guest in her house, acquired his works and exhibited his latest works “Sacred arts, religious subjects” in 1947 at her premises in Avenue Foch 21 in Paris.[98] She supported the artist during the seven years that followed, organised the commemorative exhibition in 1961 in the Galerie Karl Flinker in Paris and bequeathed important works by Kirszenbaum from her collection to Israeli museums.

[83] Letter dated 20 April 1945 (see comment 57)

[84] Quoted from Frédéric Hagen: J.D. Kirszenbaum = Galerie Karl Flinker exhibition catalogue, Paris 1961 (see comment 7), in: J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013, page 78 f.

[85] J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see Literature), page 98

[87] see the Solinger exhibition in this portal, https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/atlas-der-erinnerungsorte/jesekiel-kirszenbaum-ausstellung-solingen, Fig. 18, 19

[88] J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see Literature), page 80 f.

[89] ibid., page 97, 100

[90] “By the rivers of Babylon we sat and wept

when we remembered Zion.“ (Psalm 137, 1)

[91] See the Solinger exhibition in this portal, https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/atlas-der-erinnerungsorte/jesekiel-kirszenbaum-ausstellung-solingen, Fig. 22, 23

[92] Photograph from 1945 in the Pompidou Centre, Paris, MNAM-Bibiothèque Kandinsky, depicted in J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see Literature), page 106

[93] J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see Literature), page 102 f.; https://www.kirszenbaum.com/france?lightbox=imageh5n

[94] Photograph in the Pompidou Centre, Paris, MNAM Kandinsky Library/MNAM-Bibiothèque Kandinsky, depicted in J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see Literature), page 84; painting in private ownership

[95] J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see Literature), page 68

[96] See the Solinger exhibition in this portal, https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/atlas-der-erinnerungsorte/jesekiel-kirszenbaum-ausstellung-solingen, Fig. 20

[97] Works of Kirszenbaum in the possession of the National centre for the fine arts/Centre national des arts plastiques, Paris, see http://www.cnap.fr/collection-en-ligne/#/artworks?layout=grid&page=0&filters=authors%3AKIRSZENBAUM%20Jecheskiel%20David%E2%86%B9KIRSZENBAUM%20Jecheskiel%20David

[98] Invitation card depicted in J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see Literature), page 82

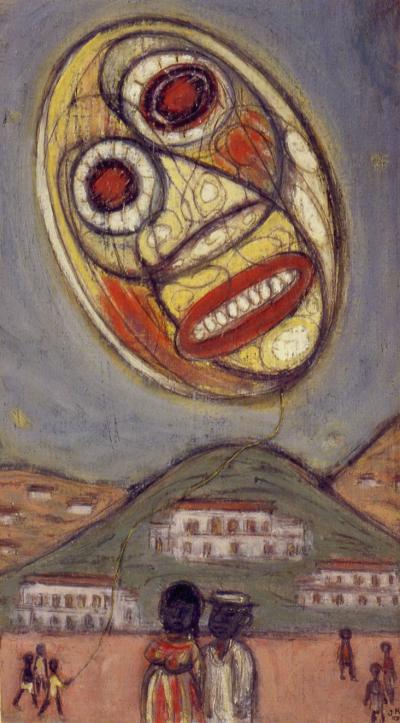

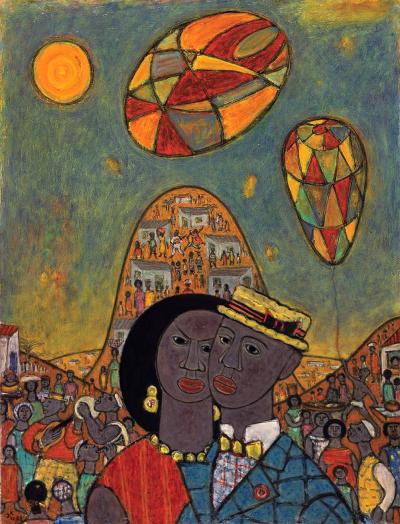

Kirszenbaum’s newly awakened courage to face life head on is evidenced by the amount of travelling he did in the following years. In 1948/49, he travelled to Brazil where the country and its people in the tropical climate inspired him to create colourful if not seemingly naive tableaux. His paintings of a “Brazilian woman with child”,[99] a “Brazilian woman with basket”[100], of “Brazilian masks”[101], of a “Brazilian boy with kite” (Fig. 53) and the “Festa de São João in São Paulo”, painted from memory three years later, (Fig. 54, 55), with their areas full of pure colour, are influenced by the Fauves, but also by indigenous painting and are not free of visionary experiments with colour. In Brazil as well, where the Jewish painter Lasar Segall (1891-1957), who came from Vilnius and belonged to the Dresden Secession, had lived in São Paulo since 1924, Kirszenbaum was able to make contacts and received a warm welcome. In 1948, he exhibited his works in the leading art gallery in São Paulo, the Galeria Domus, and in the Instituto de Arquitetos do Brasil in Rio de Janeiro.

When he returned to France, he was made a German citizen in 1949. In the same year he illustrated the 50-page volume of poems by the German-French writer and poet Frédéric Hagen (Friedrich Hagen, 1903-1979), “Paroles à face humaine”. The book with eight illustrations by Kirszenbaum appeared in a numbered edition of five-hundred books in the Paris publishing house of the surrealist poet Guy Lévis Mano (1904-1980), GLM. Kirszenbaum remained close friends with Hagen, who like the painter had fled to France in 1933, until the end of his life.[102] In 1948/50, he travelled to Morocco and Italy,[103] where he turned his artistic interest to nature, especially to fruit and plants. Two still lifes of fruit produced in 1952,[104] one of them in the collection of the Centre national des arts plastiques,[105] conjures up memories of similar motifs by Cézanne, but their moderate cubism brings them closer to Picasso. A completely new motif, the view of a slaughterhouse in Paris, in front of whose open displays ladies with shopping baskets take their dogs for a walk,[106] is similar to the Brazilian pictures with its bright colours and the naive style of the figures.

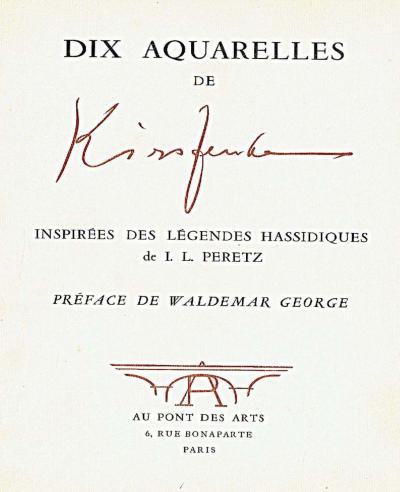

Kirszenbaum’s religious themes, including the juxtaposition of Christian and Jewish subject matters, now began to enjoy public attention public attention as well. In 1951, the well known Polish-French art critic Waldemar George (Jerzy Waldemar Jarociński, 1893-1970) wrote in the eight-page catalogue to accompany a retrospective of Kirszenbaum, with paintings, watercolours and gouaches at the Galerie André Weil in Avenue Matignon 26 in Paris: To a great extent, Kirszenbaum has contributed to the resurrection of a Jewish art of painting whose spirit is closely related to Jewish poetry. Like other illustrators of the Old Testament, he has also experienced the strong pull of the Legenda aurea (the non-biblical legends of the saints). Instead of contradicting each other, “synagogue” and “church” (Judaism and Christianity) merge in the work of this visionary (this means Kirszenbaum), who views the universe with fascinated eyes.[107] In 1953, the artist had an exhibition in the Galerie Au Pont des Arts in Rue Bonaparte 6. This gallery published a bibliophile edition with ten of Kirszenbaum’s watercolours, reproduced in a print run of one hundred copies, which illustrate Hasidic legends by I.L. Peretz. The foreword was written by Waldemar George.[108] Kirszenbaum’s illustrations essentially recapitulate earlier motifs, such as the blind fiddler, studying rabbi and the water carrier from Staszów, but also show a previously unknown scene of travelling entertainers (see PDF 3).

[99] See the Solinger exhibition in this portal, https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/atlas-der-erinnerungsorte/jesekiel-kirszenbaum-ausstellung-solingen, Fig. 28

[100] J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see Literature), page 121

[101] See the Solinger exhibition in this portal, https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/atlas-der-erinnerungsorte/jesekiel-kirszenbaum-ausstellung-solingen, Fig. 29

[102] It is not known when Hagen and Kirszenbaum first met. The previous assumption that they knew each other from the Bauhaus in Weimar (J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013, see Literature, page 26) is unlikely. Hagen trained as an art teacher at the teacher training college in Schwabach from 1919 to 1922 . From 1923 to 1930, he resided in Nuremberg working as an employee at different newspapers, as a theatre play director and art critic. He worked as an art critic in Paris in 1935 and was a member of the associations of antifascist artists and authors, from 1945 to 1950 he was editorial director of German programmes for the French broadcasting service (Friedrich Hagen: Curriculum Vitae, in: Friedrich Hagen, Leben in zwei Ländern, published by Godehard Schramm, Nuremberg 1978, page 198-201). Hagen was friends with authors and poets of his day, such as Paul Éluard, Jean Cocteau, André Breton and Paul Celan.

[103] The Bauhaus Archive in Berlin houses a watercolour drawing “Tuscan Landscape – San Gimignano”, 1948, Inv. No. 3574

[104] See the Solinger exhibition in this portal, https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/atlas-der-erinnerungsorte/jesekiel-kirszenbaum-ausstellung-solingen, Fig. 28

[105] http://www.cnap.fr/collection-en-ligne/#/artwork/140000000035452?layout=grid&page=0&filters=authors%3AKIRSZENBAUM%20Jecheskiel%20David%E2%86%B9KIRSZENBAUM%20Jecheskiel%20David

[106] J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see Literature), page 122

[107] Waldemar George in: J.D. Kirszenbaum. Paintings, watercolours, gouaches. From 27 September to 11 October 1951, exhibition catalogue from Galerie André Weil, Paris [1951], quoted from: J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see Literature), page 108 f.

[108] Ten watercolours by Kirszenbaum. Inspired by the Hasidic legends of I. L. Peretz. Preface by Waldemar George, Paris: Au pont des arts, 1953

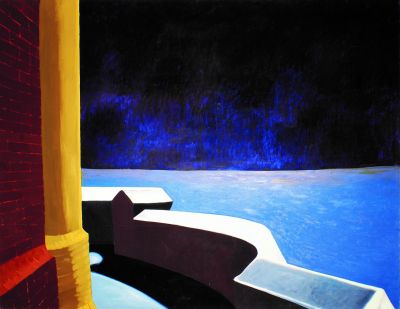

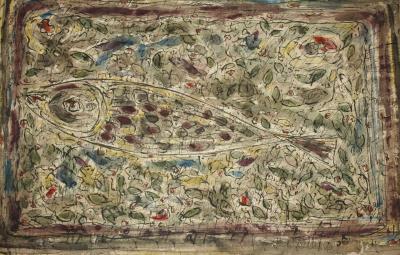

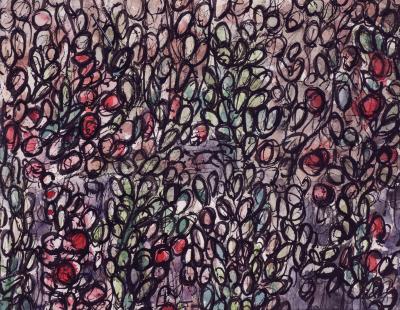

Diagnosed with cancer at the beginning of the 1950s, Kirszenbaum reflected on his time at the Bauhaus in a series of abstracted or complete abstract images. At first glance, two watercolours showing fish in front of abstract backgrounds (Fig. 56, 58) are reminiscent of the painting produced by Paul Klee in 1925 entitled “The Goldfish” (Hamburg Art Gallery/Hamburger Kunsthalle). The artist constructed watercolours and gouaches using abstract textures (Fig. 57) and arabesques from free organic forms, like the ones created by Mondrian and Kandinsky around 1910. The combination of figurative and free-form shapes, as seen in his watercolour of an “Abstract garden”[109], is also reminiscent of Roger Bissière, a member of the École de Paris, who in his early years also modelled his work on Klee’s style. A last recollection of Staszów, “The Prophet Elijah” (Fig. 59), follows on from the images of the Arrival of the Messiah in the shtetl, and shows the familiar folksy figures in front of the backdrop of the town. However, the prophet, not the Redeemer, becomes the main figure who, according to biblical tradition, is carried away to heaven by fiery horses (2 Kings 2, 11).

Kirszenbaum died of cancer in 1954. Retrospectives were held in 1955 in the Galerie Tsavta in Jerusalem and in 1962 in the Galerie Karl Flinker in Paris in the Rue du Bac 34. Friedrich Hagen wrote an extensive essay about the artist’s life and work in the Flinker catalogue.

Axel Feuß, October 2019

We would like to thank the great nephews of Jesekiel Kirszenbaum, Nathan and Amos Diament (Tel Aviv) for generously providing us with information, photographs and permission to reproduce the works, and we would also like to thank Ms Anna Taube (Osnabrück, formerly of the Goethe Institute, Tel Aviv) for her kind support in acquiring information.

Literature:

Yechezkel Kirszenbaum: Childhood and Youth in Staszów. From “Life Chapters of a Jewish Artist”, translated by Leonard Levin, originally in Hebrew in: Sefer Staszów (The Staszów Book), published by Elhanan Erlich, Tel Aviv 1962, page 221-229, online: https://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/staszow/sta221.html; again in: J.D. Kirszenbaum 2013 (see below), page 129-170

Revolution and Realism. Revolutionary art in Germany 1917 to 1933, Exhibition catalogue, Berlin State Museums/Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, (East) Berlin 1978

Inna Goudz: Herwarth Walden and the Jewish artists of the Avantgarde, in: Der Sturm. Centre of the Avantgarde, Volume 2: Essays, Exhibition catalogue Von der Heydt-Museum, Wuppertal 2012, page 515-540

Johanna Linsler: Jesekiel David Kirszenbaum, between revolutionary ambition and memories of the shtetl/Jesekiel David Kirszenbaum, entre aspiration révolutionaire et mémoire du shtetl / Jesekiel David Kirszenbaum, zwischen revolutionärem Streben und Erinnerungen an das Schtetl, in: Anne Grynberg / Johanna Linsler: L’Irréparable. Itineraries of artists and amateurs of Jewish art, refugees of the “Third Reich” in France/Itinéraires d’artistes et d’amateurs d’art juifs, réfugiés du „Troisième Reich“ en France / Irreparabel. The lives of Jewish artists, and art connoisseurs on the run from the “Third Reich” in France/Lebenswege jüdischer Künstlerinnen, Künstler und Kunstkenner auf der Flucht aus dem „Dritten Reich“ in Frankreich, published by the Koordinierungsstelle Magdeburg, Magdeburg 2013, page 265-289 / 290-314

J.D. Kirszenbaum (1900-1954). The Lost Generation. From Staszów to Paris, via Weimar, Berlin and Rio de Janeiro / La génération perdue. De Staszów à Paris, via Weimar, Berlin et Rio de Janeiro, published by Nathan Diament, Paris 2013; including: Baron David de Rothschild: Alix de Rothschild: Student and Benefactor / Alix de Rothschild, élève et bienfaitrice, page 11; Nadine Nieszawer: Jechezkiel Kirszenbaum, a Jewish Artist of the School of Paris / Jechezkiel Kirszenbaum, un artiste juif de l’École de Paris, page 13-16; Nathan Diament: A Personal Pathway / Un cheminement personnel, page 21-32; Caroline Goldberg Igra: Kirszenbaum’s Artistic Journey / Le parcours artistique de Kirszenbaum, page 35-124

Caroline Goldberg Igra: The Restoration of Loss: Jechezkiel David Kirszenbaum’s Exploration of Personal Displacement, in: Ars Judaica, published by the Bar-Ilan University, Faculty of Jewish Studies, Department of Jewish Art, Nr. 10, Ramat Gan 2014, page 69-92

Nadine Nieszawer / Deborah Princ and others: Artistes juifs de l’École de Paris 1905-1939 / Jewish Artists of the School of Paris, Paris 2015, page 177 f. / 428 f., online: http://ecoledeparis.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/1.pdf

J.D. Kirszenbaum (1900-1954). Retrospektiva/Retrospective, exhibition catalogue Muzej Mimara/The Mimara Museum, Zagreb 2018

All electronic links were last accessed in October 2019.

Video:

On the occasion of International Holocaust Remembrance Day on January 27, the Willy Brandt Center in Jerusalem is dedicating itself to J.D. Kirszenbaum with a film: https://www.youtube.com/watch?fbclid=IwAR02r8UDCLPmFRa_SQznLW4zMTpgJG_lM7mDwYbC1kNNRoVyU09LIhnIvms&v=JsUXlvHp06I&feature=youtu.be

[109] See the Solinger exhibition in this portal, https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/atlas-der-erinnerungsorte/jesekiel-kirszenbaum-ausstellung-solingen, Fig. 26