Camaraderie and solidarity at Opel in Bochum. Bochum’s Opel workers with a transnational background share their recollections.

Geopolitical conflicts in the 19th century, two world wars in the 20th century and ultimately the collapse of the communist states in Central and Eastern Europe towards the end of the 1980s caused families to be ascribed various nationalities as Germans, as Poles or as Czechs as, time and again, new borders were drawn between Poland and Germany over many generations. These attributions were created by banal border shifts, despite the fact that the majority of the family members had seldom left their home town. In the meantime, generations of primarily male household members from the border regions migrated to the Ruhr area, which had seen rapid growth since the 19th century as a result of industrialisation.

And so it came to pass that, before the First World War, the great-grandfather as a German from Upper Silesia temporarily migrated back and forth to the Ruhr area – so within the German Reich – so that he could work in the mines during the winter months and in the fields back home during the summer. Then, the grandfather worked in the era of the Weimar Republic as a Pole in the companies involved in the coal and steel economy and then the father, again as a German until the end of the Second World War – along with Polish and Eastern European forced labourers – worked in the pits and in the armoury smithies of the Ruhr area. Finally, in the 1960s, the son took up work at Opel in Bochum as a Polish migrant worker and ultimately united the family from Upper Silesia in Bochum. His children, who were born in the Ruhr area, bettered themselves through education, completed their school-leaving exams and studied at the Ruhr University, started families and, today, work as academics in the Main-Rhine region; all of them like to travel to Silesia in the holidays. Up until the Oder-Neisse border treaty was concluded in 1990, migrants from Poland, particularly from the border region of the former German Upper Silesia, made up the largest group of emigrants in the Ruhr area. To this day, their living and working environments move in the transnational space between integration in everyday German work and life, deep cultural connection to the home region of Upper Silesia and their dominant socialisation in Poland. For centuries, their nationality – whether German or Pole – was merely the result of external attributions and a fluctuating entry in passport documents. In fact, their identities were actually transnational in nature.

This understanding of transnational spaces and identities, developed as a bundle of phenomena resulting from social interactions across national state borders, is critical to the characterisation of employees with cross-border, Polish-German roots at Opel in Bochum. The Opel plants themselves ultimately turned out to be transnational social spaces where special social structures of camaraderie developed, conflicts between different employment groups were certainly created, but also solidarity between colleagues was generated within the context of the company in which, ultimately, the mere formal attribution of a national heritage lost its meaning compared with the everyday experience of camaraderie in the shared social space of the company.

The Opel plants in Bochum – an attractive employer for 30 years

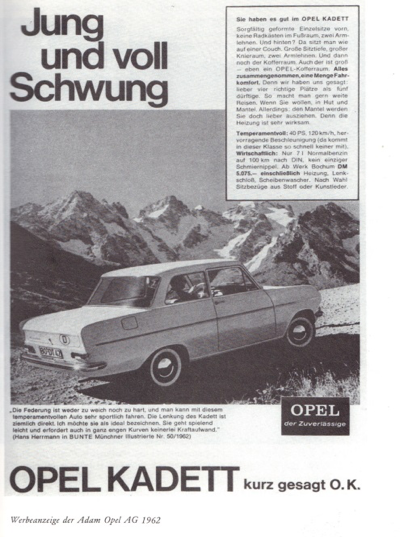

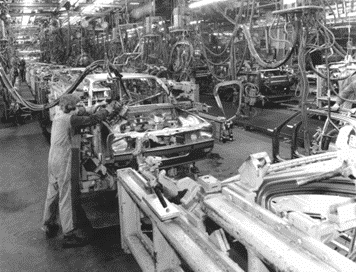

Whilst mining and the iron and steel industry of the Ruhr area had meant good earning potential for the great-grandfather and grandfather generations of migrant workers from present day parts of Poland during the first modern age of industrialisation, for the generation of late emigrants this was embodied by the many thousands of jobs created since 1962 at Opel Bochum, a subsidiary of the General Motors Group from the US that had acquired Opel in 1929. Established during the first peak of the mining crisis at the start of the 1960s, the only car facility in the Ruhr area to date developed into a particularly desirable employer with more than 22,000 employees in the 1980s. During this heyday, the legendary models included the Kadett, GT, Manta and Ascona, followed later by the Zafira. The establishing of Opel was the starting point for Bochum’s second modern age, which was followed by other significant sites being established, such as the Ruhr University and the Ruhr Park shopping centre, which changed not only the picture of the town, which had once been defined by coal and steel, but also its attitude to life. For 30 years, into the 1990s, having a job with Opel particularly meant secure terms and conditions of employment. In this phase of Bochum’s second modernisation, the fear of losing your job was an unknown. Willi Gröber, an Opel worker from the very beginning, and later on the works council and ultimately trade union secretary with IG Metall in Bochum, remembers: “At Opel you really had to steal golden spoons to lose your job.” The car became a symbol of the town’s recovery which seemed to overcome the effect the coal crisis had had on the labour market. It continued merrily on the up for many decades or it was simply OK!

This good quality of life based on secure income and working conditions only began to change gradually for the Opel workers in Bochum in the 1990s. During the formation of the single European market and the collapse of the Iron Curtain, the large German car manufacturers, with Volkswagen and Opel leading the way, started to develop cross-border production and supplier networks which were supposed to allow management to compare labour and production costs between various sites in Europe. These business analyses ultimately created the conditions for playing off employees from different production sites against each other.

For Opel in Bochum, the opening of the Opel plant in Gliwice in Upper Silesia in 1998 played an important role. Although only the Opel Astra from Bochum was built in Poland at first, this was then followed by the Zafira which made cost comparisons between the two sites easier. The establishing of Opel as an attractive employer in Silesia was of similar economic significance to the people there as it had been in Bochum in the 1960s. In Poland, Opel also made a considerable contribution to the region’s economic upturn and to the positive changes in its industrial structure. For the employees at Opel in Bochum, however, the new site in Gliwice started a phase of open competition around maintaining jobs and securing earning opportunities, just as the European management at Opel had intended, and this competition was partly responsible for production capacities being moved within Europe and finally to the closing of Opel Bochum in 2014 – after 52 years. Ultimately, the somewhat outdated Opel plants in Bochum were no match in the battle to compete with the comparatively young sites within Europe and their lean production concepts based on the Japanese Toyota system.

Former Opel workers with German-Polish backgrounds remember.

Lothar Degner came from Upper Silesia to Bochum with his family in 1965 at the age of two. He was born in Bytom near Gliwice. At the time, two of his father’s brothers were already living in Bochum and his parents had wanted to return to Germany for a long time. As Upper Silesians with German heritage, they had not felt completely integrated in Poland. Their decision to move to Bochum was also prompted by the better than expected economic conditions in Germany. Lothar Degner’s uncle worked at Opel. He often told his nephew how financially lucrative work in the car plant was; a fact which he emphasised by showing him his wage slips. At first though, Lothar Degner did not want to work at Opel in Bochum, despite the clear financial advantages over his job at the time. He could not imagine ever being able to do “such moronic work as working on an assembly line”. After a while, however, his family were able to talk him round and he started work as an assembly worker on the assembly line at Opel in Bochum. He later moved to another department and was also on the works council.

Andreas Gilner and Eduard Popanda moved to Bochum with their families in 1971. Andreas Gilner was 11 years old at the time. He was born in Gliwice. His grandmother was already living in the Ruhr area so they moved to Bochum to reunite their family. His father had worked at Opel since 1971 and he also brought Andreas Gilner to Opel in Bochum. He worked as a skilled production worker at the plant from 1984 until it closed in 2014.

Eduard Popanda was born in Oppeln and came to Germany when he was five. He also had relatives who were already living in Bochum. The fact that his father had been accepted at Opel was another reason for the family to migrate. So the transnational family background also led Eduard Popanda to Opel in Bochum. As well as his father, his uncle and his cousin also worked at Opel. Before he was employed by Opel, he worked as an assembly worker and earnt more doing that than he did later on at Opel. At first, Eduard Popanda could not imagine working on the assembly line at Opel either. But family circumstances, including the birth of his child, meant that he did ultimately decide to take a job with Opel in Bochum. In 1988, he started in Plant I as a skilled production worker in the press shop. After Plant I was closed, he switched to what was previously Plant III, and in 2021 he is still working there as a picker. This has meant a big adjustment for him as his work has changed significantly:

“The things I used to produce, I’m now packing.”

Johannes Nowak moved to Bochum with his family in 1978 and was 17 years old at the time. He was born near Gliwice. Most of his close relatives were already living in Bochum and the surrounding area so here too the move to Bochum was also borne from a desire to reunite family. One year later, he started as a machine operator at Opel in Bochum and stayed there until the closure of Plant II in 2013. From his family too, both his father and uncle had also worked at Opel. For Johannes Nowak, being employed by Opel was also a matter of social security. His expectation at the time was:

“Working at Opel was a job to retirement. Working for a big group was worth a lot. And nobody ever expected Opel to close in Bochum.”

Opel Bochum: “Working to retirement”

Looking back now, all of those interviewed mainly had positive memories of their time in the Bochum car plant. Two aspects in particular were often remembered positively. First and foremost, the good and secure conditions of employment at Opel in Bochum, i.e. the above-average wages which afforded Opel workers and their families a reasonable and comparatively worry-free life. Another key aspect was the solidarity among the Opel workers in the factory, regardless of what country they came from. It was stressed that, for the most part, “the Opel workers in Bochum” stuck together in the last 10 years, even, and especially in the critical times after the first threats of closure in 2004. The national heritage of the Opel workers in the plant was irrelevant when it came to the solidarity and resistance shown during this time.

Any negative memories of the time at Opel relate to the working conditions typically associated with mass production on an assembly line, “working to a stopwatch”. “Work on the chain” was felt to be very monotonous and not very fulfilling because the employees on the assembly line always had to carry out the same activities over and over within an ever decreasing timeframe. Some of those interviewed had also become politically active in the factory so that they could advocate for improved working conditions, and were either shop stewards or on the works council to represent the interests of the Opel workers to the management.

Whether they were on the works council committee or in the plant, the interviewees spoke of the special camaraderie among the Bochum Opel workers, irrespective of their national origin. It is true that colleagues who shared the same Upper Silesian heritage and spoke Polish as their native language had a direct reference point, with this shared background helping to foster exchanges about everyday life. But at Opel, just like with the miners down the pits, no distinctions were made between colleagues based on their nationality:

“We were integrated into the department. It didn’t matter if you were Spanish, Italian, Turkish, or any other nationality – we were all just colleagues. That was a bit like the mentality in the mines as well. We were dependent on each other to make everything work to some degree.” (Johannes Nowak)

Johannes Nowak also talked about the fact that the nationality of the candidates in the works council elections was of little importance.

“A German colleague voted for a Turkish colleague too because he felt he was in better hands with him.”

Eduard Popanda was able to distinguish between the two different Opel plants - Plant I, which comprised the mass production sites in Laer, and Plant III, the spare parts store in Langendreer, which is where he worked and still does today:

“There was much more solidarity in Plant I, regardless of whether you were a Pole, a German, an Italian or a Turk. Yes, you also had colleagues there who continued to work although there was a token strike, but very few. If an action is started in Plant III, it is extremely difficult to get colleagues to join in.”

Eduard Popanda experienced a marked difference in camaraderie in Plant I and Plant III due to the different working conditions for the group on the assembly line or the individuals in the store:

“There was no or hardly any conflict at all in Plant I. In Plant III, there were more conflicts than in Plant I.”

However, none of the Opel workers could recall any conflicts being caused by different national backgrounds. Sometimes, there were smaller differences of opinion due to cultural differences, but even then, nationality was not usually a distinguishing factor. You had colleagues that you liked who were German, Polish or another nationality, and colleagues that you did not like quite as much:

“Either you got on with someone or you didn’t. But that didn’t have anything to do with where you came from.” (Andreas Gilner)

Andreas Gilner compares life in the factory with life in a family:

“If you’re hanging out together for years and there are a lot of people, then every now and then there's going to be conflict. It’s just like in a family. But it never got out of hand. You calmed down, shook hands and it was all forgotten again.”

Only a few of the former Opel workers who were interviewed could remember spending their free time with other Opel employees with a Polish-German background outside of work in the plant:

“You came from the surrounding towns, and so you would bump into each other in the various neighbourhoods. You played football together in the club, you saw each other in church, and you saw each other on trips, regardless of nationality.” (Johannes Nowak)

Football teams were also formed in the plant and mini championships were played out between the various departments. Anyone could take part, regardless of their nationality:

“It didn’t matter if you were good or bad – it was all about having fun. Camaraderie was everything. A lot of them couldn’t even play football, but you still got together and played.”

Transnational cooperation with the Polish-German colleagues from Gliwice: “Everybody is fighting for themselves.”

When the Opel site opened in Gliwice in 1998, contact gradually started to be made with the Opel workers at the Polish site as well.

“You sat there together for eight hours, there were professional interpreters then. When everybody got together, when we had eaten and drunk, I acted as an interpreter so that everyone could understand each other. I speak Polish.” (Andreas Gilner)

These cross-border contacts between the Opel workers from Bochum and Gliwice became all the more significant in the context of the strained competition between the facilities. In 2007, shop stewards, works councils and representatives of IG Metall from Bochum flew to Opel Gliwice for the first time for an informal exchange. Similarly, representatives from Gliwice were invited to Bochum. This exchange took place at the end of 2007 under the project name “Worker solidarity from below”. Many things were discussed, including experiences in developing the terms and conditions of employment at the various sites and differences in the areas of worker representation and remuneration systems.[1] The aim of these meetings was to develop a mutual understanding of the different ways the Opel workers were affected at different facilities in Bochum and Gliwice in order to counter the competition with a concept of cross-site cooperation and solidarity.

Some of the Opel workers from Bochum who were interviewed also took part in this exchange and spoke of the very special type of hospitality that was offered by the Polish colleagues in Gliwice. The went to great lengths to look after the guests from Bochum who received a very warm welcome.

“I was really surprised at what the colleagues in Poland had produced. It was like a wedding celebration for 100 people. It was really astonishing.” (Lothar Degner)

They also spoke about how, during the exchange, there were discussions on how social standards in Bochum and in Gliwice were to be evaluated and how they could be compared with one another. It became clear how much worse the working terms and conditions were in Gliwice compared to Bochum:

“Here in Bochum, we have a lot of social standards. People with limitations don’t have to do any heavy work or bend down. But there’s nothing like that in Poland. If you got ill, you were thrown out. Even though in Bochum at the end, you had to work a lot and you had to work fast because many people had been let go, the social standards here were much better than those in Poland at the time.” (Andreas Gilner)

[1] Bauer, Markus: “Arbeitnehmersolidarität von unten” from 8 to 11 November 2007 in Gliwice. Project information. 2008.

Andreas also noticed that the average age of the employees at the Opel plant in Gliwice was considerably less than that of the Opel workers in Bochum. Also, the workers there were expected to do much more work and work that was physically much more demanding. Overall, those interviewees who had taken part in the international exchange remembered it very positively. Contact details had also been swapped sporadically between Polish and German participants. Today, however – seven years after the plant closed in Bochum – the interviewees no longer have any contact with the Polish participants.

The Opel workers interviewed vividly remember the period before Opel closed in Bochum. On the one hand, they remember the strong solidarity of the Bochum Opel workers, on the other hand they also express their disappointment that there was little to no international solidarity during the ten-year fight. According to the statements made by the Bochum Opel workers who were interviewed, apart from sending formal letters of solidarity, notably their Polish colleagues from the Opel site did not reach out to their colleagues in Bochum. Instead, the impression was formed that, particularly at this time of deep crisis within the General Motors Group, each facility, and each plant with its employees were thinking about themselves and about their own preservation. However, this was not just the case at the Polish facility; it was also happening at other national and other European facilities as well:

“They were happy that we had closed because that secured their chances of survival. One plant was played off against another. From a human perspective, they perhaps thought ‘what a shame’, but secretly they were happy that we closed because it meant they could continue to produce. They were happy in England, in Rüsselsheim or wherever. Everyone looks to themselves first to make sure that they’re OK. Your own plant is the important one, that that’s the one that is preserved.” (Andreas Gilner)

Andreas Gilner is by no means the only one to express this opinion:

“Well, I would say that there wasn’t any solidarity at all. Something was always being professed, but you knew very well that each site was fighting for itself. And it doesn't matter what was professed, basically everyone protects their own backside.” (Johannes Nowak)

Johannes Nowak even knew the second chair of the works council at the Opel plant in Gliwice personally and, during the period of tough confrontations around the closure of the Bochum plant, had spoken to him about possible support from the workforce in Gliwice. He had felt supported by him personally but on the whole he summarised by saying:

“We didn’t experience any proper solidarity from any plant really. We didn’t get it from the Austrians or the Rüsselsheimers. It’s true that various committees were set up, but at the end it’s all about the survival of your own plant. Everyone wants to keep their job and wants it to continue.”

Any expectation that a transnational solidarity could have developed between the groups of workers at the Opel plants in Bochum and Gliwice based on their shared German-Polish heritage disappeared under the painful experience of the open competition between the European Opel facilities, which ultimately undermined the tentative beginnings of a cross-border European collaboration that had started in 2007:

“It's understandable. Our colleagues in Gliwice had been tormented for decades. We were reproached for how cheap they are in Gliwice and how expensive we are in Bochum and our colleagues in Gliwice were reproached for how cheap they are in the Ukraine. It’s a spiral. So, when it’s a question of your own future, I do understand the individual plants.” (Eduard Popanda)

Summary

The recollections of the former Bochum Opel workers with transnational German-Polish roots allow two conclusions to be drawn:

- Opel Bochum can be characterised over five decades as a transnational social field. The national heritage of the workers played a very subordinate role in the collaboration, camaraderie and solidarity engendered among the many thousands of workers. Whether German, Pole, Spaniard or Turk, Christian, Muslim, woman or man; first and foremost, the organisation of work in mass production on the assembly lines united the workers on a daily basis, day and night, and created the basis for cooperative working relationships, for experiencing daily solidarity and for conflict resolution among themselves. The organisation of the industrial enterprise with high levels of trade union membership promoted the creation of very stable employment and pay conditions right into the 1990s. The common aim of the Bochum Opel workers was to maintain these stable social conditions to give their families a life that was as free from worry as possible and to advance their children, and to do this they also got involved in company and trade union politics. This meant that for over five decades the organisation of the Opel industrial enterprise had a much greater influence on forming their identity than their German-Polish biography.

- The fact that the Opel workers’ national heritage was almost meaningless in terms of developing a cross-border collaboration was highlighted in the conversations with the Bochum Opel workers, particularly in the context of the open competition with the new Opel facility in Gliwice. Whilst the Opel management, with its strategy of competitions or ‘beauty contests’ around production capacities at different facilities, played the workers off against each other at the European facilities and put the Bochum plants under pressure from 2004 onwards with several announcements of closure, the project “worker solidarity from below” was supposed to build a bridge of solidarity between the Opel workers in Bochum and Gliwice. Inspired by the 2007 visits, the hope that the Upper Silesian heritage of the employees at both facilities would make it easier to create a cross-border solidarity disappeared as each facility and its workers fought its own battle to survive, a battle which the workers in Bochum lost in 2014. It is, however, remarkable that, after the facility closed, the Opel workers in Bochum with Upper Silesian roots showed an understanding for how their colleagues in Gliwice behaved.

Jennifer Müller / Manfred Wannöffel[2], March 2021

[2] Jennifer Müller, B.A. in general rhetoric and international literature; Prof. Manfred Wannöffel, lecturer at the Ruhr University in Bochum