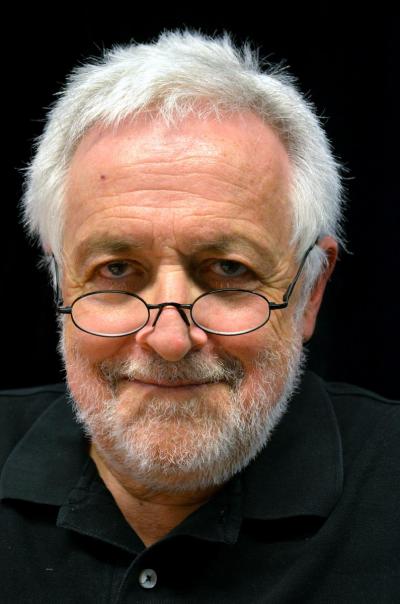

Henryk Marcin Broder: German thinking with Jewish rationality and a Polish heart

The world and the axis of good

Henryk Marcin Broder’s critical journalism is feared by many and is loved by many (often secretly). Given his fascinating, unconventional and pointed statements, ambivalence is not an option. What is striking is the fact that his astute analyses are preceded by a very particular talent for observation which is marked by a love of detail. The key to his success, however, comes from a special mixture of irony, sarcasm, provocation and entertainment that only he has.

Henryk M. Broder was born Henryk Marcin Broder into a Polish-Jewish family in Katowice in Upper Silesia, Poland on 20 August 1946. In 1957, his family left for the West, presumably because of the noticeable rise in anti-Semitism at the time[1], first travelling to Vienna and then, in 1958, to the Federal Republic of Germany where they stayed permanently.

Eleven years in Poland would certainly have left their mark on him and shaped not just the start of his life in his new home but presumably his entire life there. He was probably predestined to write. He started writing very early on in Hamburg and discovered the power of words. German is his working language, he can still speak Polish without an accent today, Hebrew comes naturally to him, and Russian (where his father came from) is probably active when called upon.

When he began his work as a journalist, he appeared to enjoy working on all aspects of the world. Injustice, the atrocities of power, the abysses of politics, but also the constant pursuit of the “unbearable lightness of being”[2] would all become important topics for him that have endured to the present day. Broder, and this is probably the main characteristic of emigrants from Eastern Europe, is notoriously and occasionally annoyingly curious and permanently on the go so that he can see as much as possible without the fear of missing out. He became a keen observer but this keenness has an almost microscopic character and, in his writings, sometimes results in a curious choice in the meaning of his subject matter. He seems to want to tell us that you can sometimes read more from the details that are usually overlooked than is the case with the motifs that the mainstream prefers to focus on.

This type of perspective can often be seen in migrants from Poland who really scan American films from the golden era of Hollywood – one of the few windows to the world in their long isolated country – for this type of detail, which viewers from the West would not even think about. Their curiosity about life behind the iron curtain was simply so great that they were not just interested in how the famous actors looked, they were also fascinated by the environment, the props, the behaviours and generally any scraps of reality which would help them read this far-off world.

[1] See https://www.jstor.org/stable/3252278?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

[2] Milan Kundera, Unbearable lightness of being, (Czech: Nesnesitelná lehkost bytí) 1984

Another characteristic of migrants from Poland, which obviously also shaped Broder, is the fear of the question about their heritage and their national identity. If you first have to find yourself and then position yourself in your new environment, then answering that kind of question does not just seem impossible, it is also annoying. In most cases, the so-called majority societies simply do not understand this aspect. This has been experienced particularly by prominent Germans of Jewish and Polish heritage, including Marcel Reich-Ranicki, and so they have consistently refused to give answers or have used symbolic literary constructions to sidestep the question.

Perhaps this is also the reason why Broder, like most migrants, feels so at home in the United States of America, a country in which, as a foreigner, you simply belong, almost as an incontrovertible matter of course.

From the 1970s, Broder addressed issues relating to the re-emerging anti-Semitism in Germany. It was in this context that his infamous confrontation with the left-wing scene occurred, which had two particularly serious consequences: Broder became a bestselling author and he left Germany for Israel in 1981. Without planning to, he ended up living there for ten years.

From his writings from this time, it is clear that Broder had systematically developed an analytical rationality which he used to deal with the complexity, taboos and tensions in German-Jewish relations in the future. The intellectual precision of his analyses and reasonings are characteristic of him. And in this way, his work is undoubtedly one of the birthplaces of a new Jewish rationality, which is aimed particularly at guaranteeing security for Jews and their state in the face of the new global anti-Semitism.

The unmasking of political untruths and the fight against that which Jean-Paul Sartre called the mauvaise foi[3] (bad faith – the insincerity towards oneself) runs like a red thread through Broder’s work and through his increasingly intensive media presence. For Broder, this special feature of the psyche, which Sartre considered a basic characteristic of human existence which one cannot cast off, is one of the main reasons for the misunderstandings between humans, against which he repeatedly takes up the fight.

[3] Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness, (L’être et le néant. Essai d’ontologie phénoménologique, Librairie Gallimard, Paris 1943, German edition: Das Sein und das Nichts, Versuch einer phänomenologischen Ontologie, Reinbek bei Hamburg, 1991, p. 154

As an author, Broder apparently likes to make himself unpopular and particularly likes those people who do not like him, as he repeatedly says. The fact that he then coquettishly overplays his belief in the good and his hope of something better in the face of everyday atrocities is part of the romantic side of the eccentric self-promoter. This is particularly evident in his talk show appearances, some of which enjoy cult status, such as the legendary discussion with the famous boxing adversaries Graciano Rocchigiani and Dariusz Michalczewski on the “Markus Lanz” programme on 2 February 2014. Several times during the programme, the legendary “Tiger” Michalczewski addressed Broder in Polish.

Much has been said about Broder in the last few years, whenever he was awarded his numerous prizes and accolades, and this can easily be found on the Internet and, being his preferred medium at the moment, that will no doubt delight him. What makes him so unmistakable in the German journalist scene?

Perhaps it is his Polish heart: his feel for the absurd, his tendency to strongly exaggerate, his curiosity, genuine awareness of details, deification of irony, Vulcan-like emotionality, imparting of knowledge through symbolism, humour and anecdotes, emphasising the power of the imaginary, the love of the paradox, a tendency towards healthy fatalism, melancholy or overstated outrage; it is an aversion to manipulation, a notoriously destructive fundamental attitude in the constant search for the positive, occasionally the purely Polish characteristics of “pieniactwo” and “warcholstwo”, which cannot be translated exactly into English but which mean: I have something to say about everything and I am a quarrelsome troublemaker. Also characteristic of Broder’s Polish heart are possibly his romantic soul, detachment and openness as a way of living and working, affirmative disinterest in materials, longing for security and probably the most important characteristic: the belief in love as the ultimate driving force.

For decades, Broder has shaped the scene of the fourth estate, i.e. the free press. Much, very much has been written about him and the phenomenon that is Broder has been publicly analysed with, at times, an eerie meticulousness. Despite this, it can be assumed that we only know a fraction of this multifaceted personality. However, his ever present ironic smile in the electronic media tells us: Don’t worry, that’s not all by any means because I still have lots to say and: You won’t get rid of me that easily. In the end, the calculation of rationality seems to be greater than his emotionality.

Henryk Marcin Broder has been a columnist at the daily newspaper Die Welt since 2011. Based in Berlin, he is constantly on the go.

Jacek Barski, July 2018

The official website of Henryk M. Broder:

Henryk M. Broder with his mother, presumably still in Katowice:

http://henryk-broder.com/hmb.php/blog/article/1045

Die Achse des Guten von Henryk M. Broder:

http://www.achgut.com/dadgdx/index.php/author/mbroder

Wikipedia entry with publications and list of accolades:

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henryk_M._Broder

Laudations (selection):

“Ihm entgeht nichts vom alltäglichen Wahnsinn”, Leon de Winter, Die Welt, 20/8/2016

Polemiker im Weltall, Michael Hanfeld, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 20/8/2016

Die nicht gehaltene Laudatio auf Henryk Marcin Broder, Dirk Schirmer, Die Welt , 20/06/2018

Appearance with numerous Polish comments from Henryk M. Broder in the Markus Lanz programme on 12/02/2014 with Graciano Rocchigiani and Dariusz “Tiger” Michalczewski: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BHNXuFZZmz8

Speech to the AfD parliamentary group in the German Bundestag on 29/01/2019: