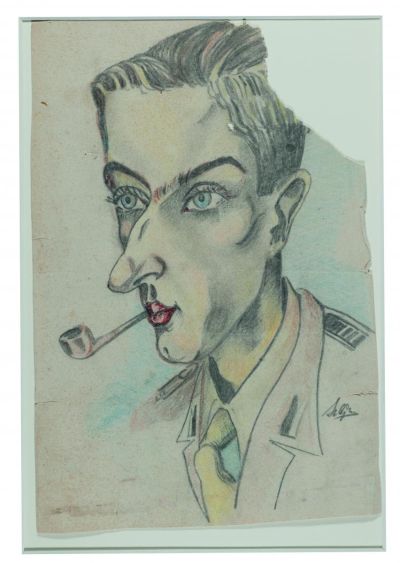

Tadeusz Nowakowski

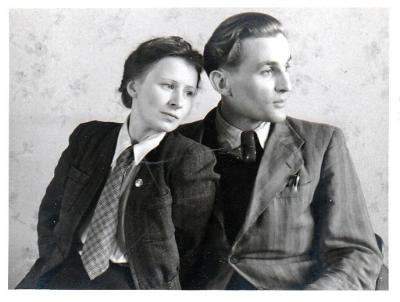

Tadeusz Nowakowski was born in Olsztyn in North-East Poland on 8th November 1917. His parents were Stanisław Nowakowski and Emilia Górka. Stanisław was a historian, journalist and Polish activist in the battle for independence in Warmia, a region in Northern Poland. When Warmia fell to Germany after a referendum in 1920, the family was forced to leave Olsztyn and moved to Bydgoszcz in the newly reborn Poland. Here Stanisław Nowakowski found a job as an editor with the local newspaper “Dziennik Bydgoski” (The Bydgoszcz Daily).

Tadeusz spent his childhood and youth in Bydgoszcz, which he regarded as his home town for the rest of his life. Here he visited the primary school and here he passed his A-levels at the public humanist Marschal-Rydz-Śmigły grammar school (Państwowe Gimnazjum im. Marszałka Śmigłego-Rydza). There he was the editor of the school paper “Ogniwa” (Connections), in which he also published his first early work. He also wrote poems and articles on the arts for the Bydgoszcz Daily, and worked as an editor on a programme for Boy Scouts at the newly founded studio of the Polish radio in Bydgoszcz. In 1936 he began a course in Polish at Warsaw University, which was named after Józef Piłsudski at the time.

After the outbreak of war he joined the Warsaw Defence Voluntary Workers’ Brigade (Ochotnicza Robotnicza Brygada Obrony Warszawy), a Civil Defence unit set up by the Polish Socialist Party (Polska Partia Socjalistyczna). He was never officially called up because he was considered unfit for military duty on the grounds of his diabetes and a visual impairment. At the end of 1939 he managed to get to Włocławek, where his mother and sisters had moved after their father had been arrested in Bydgoszcz and deported to the concentration camp there (Stanisław Nowakowski died in Dachau in 1942).

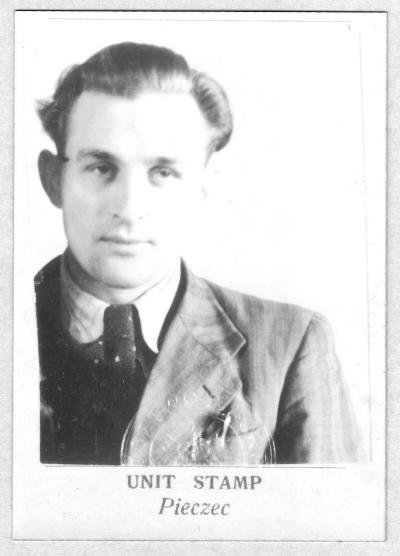

In December 1940 Tadeusz Nowakowski was arrested and accused of distributing leaflets and leading an underground newspaper. He was tried and sentenced to death on the grounds that he had led resistance activities to promote “the separation of Greater Poland from the Third Reich”. But since his German was excellent, he entered a formal appeal on the grounds that his public defenders, local “volksdeutsche” were only capable of passively understanding the German language and could only partially speak it. Hence this made it impossible for him to have an appropriate and orderly defence. The court allowed his appeal and “pardoned” Nowakowski, by commuting the death sentence to 30 years imprisonment in a concentration camp.

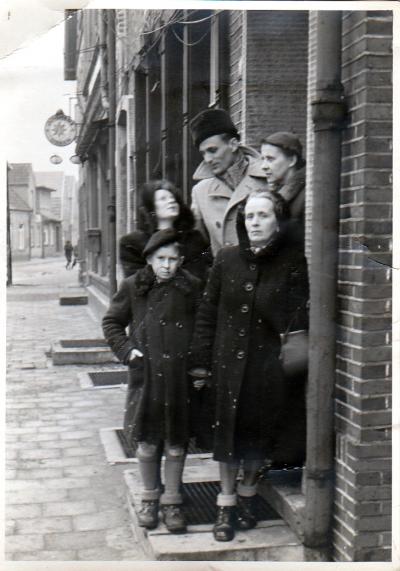

Till the end of a war Nowakowski spent the rest of his time in prisons and concentration camps: in Włocławek, Inowrocław, Bautzen, Zwickau, Dresden, Elsnig-Vogelgesang and finally in Salzwedel, where he was freed by the American army. He subsequently arrived in the Displaced Persons Camp in Haren (Ems) in the Emsland, a town that was renamed “Maczków” in honour of General Stanisław Maczek, the commander of the 1st Polish Tank Division that had liberated the town, occupied it and taken over responsibility for its administration. Here Nowakowski found a job as a teacher at a Polish grammar school. And here he developed his literary interests and wrote the initial fragments of his most important novel, as well as poems and short stories which he then sent to the Polish literature magazine “Wiadomości” (The News), that had been revived in London at the start of 1946.

Since his life as a displaced person was anything but easy and – much more importantly – his future prospects were nil, he travelled to Italy in autumn 1946 after his efforts to leave Germany proved successful. In Italy he joined the 2nd Polish Corps (at the time it was known as the Polish Training and Divisional Corps: Polski Korpus Przysposobienia i Rozmieszczenia) who had ended its campaign here and was scheduled to move to Great Britain under General Anders, where it would be demobilised in 1947.

Nowakowski was spared the quarantine imposed on soldiers in the training camps. He found somewhere to live in the Polish “House of Writers” in Finchley Road, which was supported by funds from the exile government, and here began his career as a journalist and writer. He was the head of the magazine “Poland in the World” (Polacy na Świecie), worked for the Polish Department of the BBC and wrote for the publishing houses of the “Światpol” (Światowy Związek Polaków z Zagranicy or World Association of Poles Abroad), as well as for congresses of Poles in America. In 1948 “Światpol” in London published his first major work, a cycle of short stories entitled Szopa za jaśminami, which was translated into Dutch, (“The Hute under the Jasmin) and Italian. In 1950 the book was awarded a prize by the London Catholic Publishing Centre “Veritas”, whereby it was erroneously listed in a lexicon of writers and bibliographies in a section entitled “Memoirs of German camps”.

“The Hut under the Jasmin” can in no way be regarded as a memoir, for it is a masterly work of literature dedicated to the theme of concentration camps, a cycle of short stories with an autobiographical background written by the protagonist whose name is the same as that of the author because, like Nowakowski, he is forced to endure several prisons and camps, although he avoids flashbacks and the use of past tenses. The storyteller’s companions are always the same prisoners. They turn up at intervals in several of the short stories in the cycle; in some of them as the main characters, in others as bit players, and in others yet again when they are already dead but ever-present in the consciousness of the protagonist as victims of the camp terrors. When the protagonist learns of the end of the war, he sets out on an imaginary journey (nonetheless with realistic accents) via Holland and Belgium to Paris, Rome and London, where his travels that had started in 1939 come to an end when he witnesses the victory parade.

Observing the delirious masses he is conscious that the reality of the “other world” will always remain alive in him and his fellow prisoners who he had encountered during his ordeals in the concentration camps, and that their traumatic experiences will set them apart from all those people who had never such a hellish existence. Nowakowski shows the effects of the machinery of extermination on the minds of the prisoners (and also on those of their executioners) by portraying the reality of the camps from the point of view of people who are helplessly exposed to the brutal pressures, and who can only make them bearable by resorting to irony, self-mockery, a mixture of tragedy and comedy, of sublime earnestness and primitive vulgarity.

The Hut under the Jasmin is the first post-war work of Polish literature on concentration camps, in which the Nazi executioners and officers working in the extermination apparatus are portrayed differentially. Despite his abhorrence and fury at his executioners’ behaviour the narrator in the cycle of stories is able to perceive the spiritual suffering of some Germans who were forced by the system to commit crimes against their conscience. Some of them even show signs of human feelings towards the prisoners, whereas others are so ashamed of performing their duties that they sink into self disgust. There are also those who blame the prisoners for their moral predicament and indulge their infinite hate in an excess of criminal zealousness that gradually turns into a sadistic pleasure in inflicting cruelty on others.

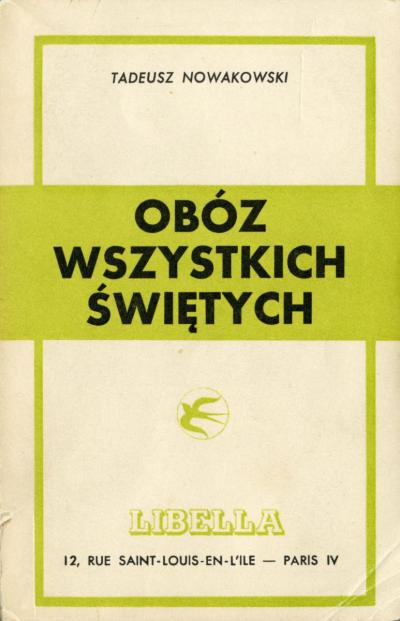

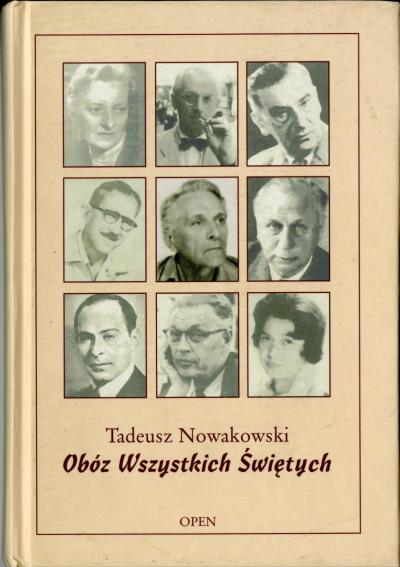

The high artistic value of this volume of short stories is defined by the differentiated portrait of the henchmen in this murderous machinery. It bears witness to the fact that Nowakowski’s work on the book was an important stage in his lengthy literary development that was to culminate in his most important work, the novel Obóz Wszystkich Świętych (Camp of the All Saints). This is one of the most important Polish novels to deal with Polish-German relationships, and the most important novel on Polish Displaced Persons in Germany. It is undeniable that it is based on autobiographical material that has been strongly reshaped and reworked into literature. Nowakowski does not set the book in Haren where he himself was a displaced person, but in Papenburg. He is always intent on describing the artificial encounters between those who had been “freed” and the local Emsland population in all its complications.

It is the first, and for many years it was the only Polish novel on the Second World War and its effects on Polish-German relationships, both the guilt of the “henchmen nation” and the guilt of the “victim nation”. Here he not only portrays Nazi crimes but also the crimes committed on the German population by those who had been “freed”. Nationalist clichés and prejudices that lead to distortions of reality and evil burden Germans and Poles alike. Every form of “patriotism” that crosses the boundary line to nationalism is equally damaging and destructive, independent of the national colours under which it is propagated. “The Camp of All Saints” is also a novel about the attempt to liberate oneself from the burden of limitations and complexes loaded onto individuals by their own society under threats of exclusion or of being stamped as anti-patriotic, a renegade, a turncoat, even as a traitor to one’s country.

After his tragic experiences during the war, the marriage of the protagonist to a German woman is only possible as an agreement between two people that can only be upheld by ignoring outside society. The Germans in the book cannot accept that one of their women chooses a Polish man, and the Poles cannot accept that a man who has fought in the underground resistance in Warsaw now has a relationship with a German. The need to be accepted by their “own” people proves stronger than their own feelings. Both of them give up, and act as if they had indeed found revealed truth in the Nationalist prejudices, which they had previously believed to be mistaken. And so they return to the lap of their own societies, full of regret for what they now see as their blameworthy behaviour.

In the novel the protagonist thinks back to his pre-war time in the town of Bydgoszcz and the relatively harmonious coexistence between its Polish inhabitants and the large German minority. Furthermore the author describes the tragic events in September 1939 when Nationalist motives gained the upper hand, gave free rein to hatred and finally led to genocide.

From 1952 onwards Nowakowski worked in the Polish Department of Radio Free Europe (RFE), which had taken up its work on 3 May that year and originally bore the name “Głos Wolnej Polski” (The Voice of Free Poland). His work then took him to Munich. For the RFE he wrote radio plays, edited programmes, interviewed writers (one of whom was Witold Gombrowicz), and commented on political and cultural events. During this time he attempted to continue his literary work as far as this was possible, by publishing novels and a huge amount of short stories in exile magazines and anthologies. His micro-novel Syn zadżumionych (The Son of the Plagued), that appeared in Paris in 1959 attracted prominent interest amongst German readers. It was the first Polish work to take up the process of Germany’s moral rebirth and the genuine desires of young people in West Germany to get their fathers to come to terms with their guilt.

The novel was translated into German under the title Der Sohn (“The Son”), adapted for radio and broadcast from Hamburg in 1963. Nowakowski reported for the RFE on war crime trials, including, from 1963 to 1965, the famous 20 month trial in Frankfurt against the people who had worked in the concentration camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Tadeusz Nowakowski received many awards for his literary work. These included the Literature Prize of the Guild of Artists in Esslingen (1959), the “Literary Atlantic Award” from Princeton University (1963), the Tukan Prize (1966) and the Karl Wolfskehl Prize for Exile Literature awarded by the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts (1992).

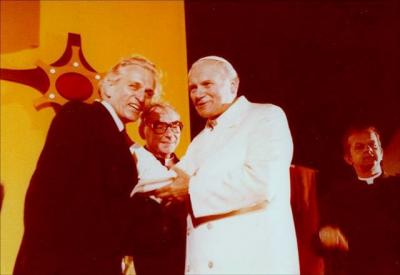

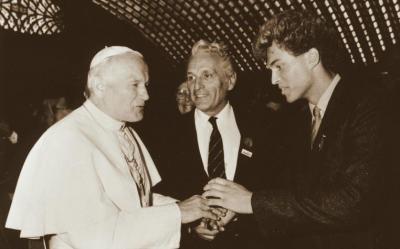

As a reporter in the service of the RFE he accompanied Pope John Paul II on thirty journeys of pilgrimage, which he also reported for the German press (“FAZ”).

After the collapse of communism he decided to revisit the country of his birth for the first time in 1990. In 1995 he moved back to his hometown of Bydgoszcz, where he died on 11th March 1996. In 1991 the town of Olsztyn made him an honorary citizen, and three years later, in 1994, he was made an honorary citizen of Bydgoszcz. Tadeusz Nowakowski was buried in his mother’s grave in the cemetery on Zaświat Street in Bydgoszcz.

Wacław Lewandowski, July 2016

Further Reading:

J. Czachowska, A. Szałagan (eds.): Współcześni pisarze polscy i badacze literatury. Słownik bibliograficzny (Contemporary Polish writers and Literary Scholars. A bibliographical lexicon), vol. VI, Warsaw 1999; vol. X (Additions), Warsaw 2007.

T. Nowakowski: Obóz Wszystkich Świętych. Introduction by W. Lewandowski, Warsaw 2003, pp. 5-15.

W. Lewandowski: Tadeusz Nowakowski. Portret literacki w 10. rocznicę śmierci (Tadeusz Nowakowski. A literary portrait on the 10th anniversary of his death), “Kwartalnik Artystyczny” 2006, No. 1 (49).

Wacław Lewandowski (born, 1962) is a literary historian, editor, and associate professor at the Nikolaus Kopernikus University in Toruń.

For all photos (except Porta Polonica): www.wolnaeuropa.pl.

Courtesy Stowarzyszenie Pracowników, Współpracowników i Przyjaciół Rozgłośni Polskiej Rdia Wola Europa imienia Jana Nowaka-Jeziorańskiego.