A forbidden love – Princess Elisa Radziwiłł and Wilhelm of Prussia

The legally approved wedding should now make it possible for Elisa to be adopted by a ruling royal house. Kamptz and Raumer presented further dossiers in which they now referred to historic adoptions in Europe. The King asked the Russians Czar to help him out by adopting Elisa, but the latter refused on the grounds that legally unapproved weddings in the Czar’s family had not been resolved this manner. An adoption into the house of Habsburg was out of the question on political grounds. The Radziwiłł family regarded the whole idea of an adoption as an additional humiliation because, according to Dagmar von Gersdorff, this would be written proof of the lower status of an “age-old Polish/Lithuanian princely dynasty” in comparison to the “more recent Prussian aristocracy”. Finally the only person who could come into question for an adoption was Prince August of Prussia, the youngest brother of Princess Luise, the Infantry General and the wealthiest landowner in Prussia. The Radziwiłłs only agreed to this proposal with the greatest reluctance, for August was regarded as a rake who had fathered no less than twelve illegitimate children. Wilhelm, who had not seen Elisa for three years, travelled to Poznan in February 1825, where they secretly became engaged.

Nobody in Berlin doubted any more that the wedding would indeed take place. Wilhelm drew up plans for his own castle in the park at Babelsberg, whilst Elisa dreamt of her new family status in Poznan. Servants turned up in the hope of being engaged by the future couple. Alarmed by the rumours of a marriage, the King once more called a conference at which his ministers emphasised that the marriage was not only undesirable, but also that an adoption would not restore Elisa’s equality in the aristocratic hierarchy. Meanwhile it had been announced that Crown Prince Friedrich would remain without an heir, and that Wilhelm would be responsible for the Hohenzollern succession. Whereas all Elisa’s women friends had long been married, she experienced the lengthy ordeal of waiting as a sort of exile. October arrived and Elisa celebrated her 22nd birthday in the new Antonin hunting lodge that Prince Radziwiłł had commissioned Karl Friedrich Schinkel to build for him in the Ostrowo district of the province of Poznan. Wilhelm had been forbidden to travel to Silesia. Instead, on the suggestion of the King, he travelled with his younger brother Carl to Weimar, where the 16-year-old Marie and her 14-year-old sister Augusta von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach were waiting for eligible partners.

Carl fell in love with Marie immediately. That said, the Princess’s mother, the Grand Duchess Maria Pawlowna, the sister of the Russian Czar and sister-in-law of Charlotte, would only agree to a marriage on the condition that Wilhelm agreed not to marry Elisa, a woman of unequal social status from a Polish family. When Czar Alexander I died in Moscow to be succeeded on the throne by Charlotte’s husband, Nikolaus I, after an officer’s revolt, Grand Duke Karl August von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach sent an ultimatum to the Prussian king in which he stated that a marriage between Carl and Marie would only be agreed to on condition that there were no links with house of Radziwiłł. Both men were basically agreed that the best solution was for the two princesses of Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach to marry the two princes of Prussia. Thereupon Friedrich Wilhelm III wrote a letter to his son Wilhelm in June 1826 in which he forbade him to marry Elisa. “The bond of love between Elisa and me has been dissolved – may her friendship with me remain – until death!”, wrote Wilhelm to both mother and daughter. Prince Radziwiłł felt deeply insulted by his family’s degradation and the fact that his daughter had been kept waiting for so long. But after writing some letters of outrage he thought twice and decided it was better not send them to the King.

Carl and Marie married in May 1827. One year later Wilhelm asked for the hand of Augusta, despite the fact that he was unable to feel any love for her. Death descended on the house of Radziwiłł. In September 1827 Elisa’s brother, Ferdinand, died of tuberculosis. Three months later Helene, the wife of Elisa’s brother Wilhelm, also died. This was followed one year afterwards by the death of their daughter, who was Elisa’s godchild. In June 1829 Wilhelm of Prussia married Augusta von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach (ill. 7), who was fully aware for the rest of her life that she would only be only an inadequate replacement for Elisa. In his final letter to Princess Luise Radziwiłł Wilhelm wrote: “You will always remain in my memory, you will always remain to me what you were, what you are! May God bless you! Yours eternally, your tender loving nephew, Wilhelm”. Following the 1830 November uprising in the Russian part of Poland, that had been led by one of Prince Radziwiłł’s brother-in-law’s, Prince Constantin Czatoryski, and his brother Michael Radziwiłł, the Prussian King relieved Prince Anton Radziwiłł of his post as vice-regent of the Grand Duchy of Poznan. In 1831 Elisa’s brother Wladislaw died of tuberculosis. Prince Anton Radziwiłł was released from service in the Prussian state in 1833 and died in Berlin in the same year.

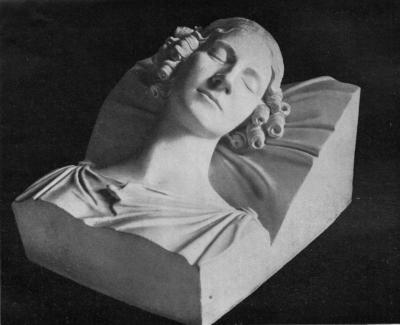

Elisa, who had ruined her health caring for her brother Wladislaw, as a result of which she was ill for years, died at Schloss Freienwalde on 27th September 1834 (ill. 8). In 1831 Princess Augusta of Prussia gave birth to a son, Friedrich, who was later to become the German Kaiser Friedrich III (the so-called 99-day Kaiser), and to a daughter Luise, the later Grand Duchess of Baden, in 1838. Wilhelm, who, even after his marriage to Augusta, met up with Elisa on several occasions, became King of Prussia in 1861 following the death of his brother, Friedrich Wilhelm IV. He was proclaimed the German Kaiser on 18th January 1871 in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles (ill. 9). The forbidden love between Elisa and Wilhelm not only fascinated the memoirs of contemporary witnesses, it has been the subject of a huge number of historical writings and novels. In 1938 it was even turned into a movie that was banned during the Nazi period, and finally shown in German cinemas in 1950 under the title “Liebeslegende” (Love Legends).

Axel Feuß, June 2016