Camaraderie and solidarity at Opel in Bochum. Bochum’s Opel workers with a transnational background share their recollections.

Opel Bochum: “Working to retirement”

Looking back now, all of those interviewed mainly had positive memories of their time in the Bochum car plant. Two aspects in particular were often remembered positively. First and foremost, the good and secure conditions of employment at Opel in Bochum, i.e. the above-average wages which afforded Opel workers and their families a reasonable and comparatively worry-free life. Another key aspect was the solidarity among the Opel workers in the factory, regardless of what country they came from. It was stressed that, for the most part, “the Opel workers in Bochum” stuck together in the last 10 years, even, and especially in the critical times after the first threats of closure in 2004. The national heritage of the Opel workers in the plant was irrelevant when it came to the solidarity and resistance shown during this time.

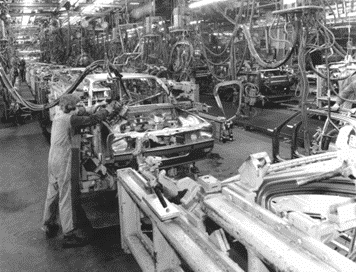

Any negative memories of the time at Opel relate to the working conditions typically associated with mass production on an assembly line, “working to a stopwatch”. “Work on the chain” was felt to be very monotonous and not very fulfilling because the employees on the assembly line always had to carry out the same activities over and over within an ever decreasing timeframe. Some of those interviewed had also become politically active in the factory so that they could advocate for improved working conditions, and were either shop stewards or on the works council to represent the interests of the Opel workers to the management.

Whether they were on the works council committee or in the plant, the interviewees spoke of the special camaraderie among the Bochum Opel workers, irrespective of their national origin. It is true that colleagues who shared the same Upper Silesian heritage and spoke Polish as their native language had a direct reference point, with this shared background helping to foster exchanges about everyday life. But at Opel, just like with the miners down the pits, no distinctions were made between colleagues based on their nationality:

“We were integrated into the department. It didn’t matter if you were Spanish, Italian, Turkish, or any other nationality – we were all just colleagues. That was a bit like the mentality in the mines as well. We were dependent on each other to make everything work to some degree.” (Johannes Nowak)

Johannes Nowak also talked about the fact that the nationality of the candidates in the works council elections was of little importance.

“A German colleague voted for a Turkish colleague too because he felt he was in better hands with him.”

Eduard Popanda was able to distinguish between the two different Opel plants - Plant I, which comprised the mass production sites in Laer, and Plant III, the spare parts store in Langendreer, which is where he worked and still does today:

“There was much more solidarity in Plant I, regardless of whether you were a Pole, a German, an Italian or a Turk. Yes, you also had colleagues there who continued to work although there was a token strike, but very few. If an action is started in Plant III, it is extremely difficult to get colleagues to join in.”

Eduard Popanda experienced a marked difference in camaraderie in Plant I and Plant III due to the different working conditions for the group on the assembly line or the individuals in the store:

“There was no or hardly any conflict at all in Plant I. In Plant III, there were more conflicts than in Plant I.”

However, none of the Opel workers could recall any conflicts being caused by different national backgrounds. Sometimes, there were smaller differences of opinion due to cultural differences, but even then, nationality was not usually a distinguishing factor. You had colleagues that you liked who were German, Polish or another nationality, and colleagues that you did not like quite as much:

“Either you got on with someone or you didn’t. But that didn’t have anything to do with where you came from.” (Andreas Gilner)

Andreas Gilner compares life in the factory with life in a family:

“If you’re hanging out together for years and there are a lot of people, then every now and then there's going to be conflict. It’s just like in a family. But it never got out of hand. You calmed down, shook hands and it was all forgotten again.”

Only a few of the former Opel workers who were interviewed could remember spending their free time with other Opel employees with a Polish-German background outside of work in the plant:

“You came from the surrounding towns, and so you would bump into each other in the various neighbourhoods. You played football together in the club, you saw each other in church, and you saw each other on trips, regardless of nationality.” (Johannes Nowak)

Football teams were also formed in the plant and mini championships were played out between the various departments. Anyone could take part, regardless of their nationality:

“It didn’t matter if you were good or bad – it was all about having fun. Camaraderie was everything. A lot of them couldn’t even play football, but you still got together and played.”