About Polish miners, “Polish mines” and “Workers from the East” – A look back at 100 years of the history of Polish workers in Bochum (1871-1973)

The First World War and the interwar period

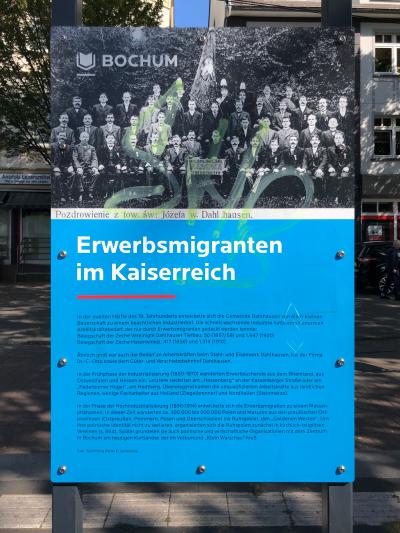

From the second half of the 19th century onwards, coal mining in the Ruhr continued to develop until the outbreak of war, which meant that the need for workers in mining and in steel production continued to increase – Bochum too, just like all the other mining districts in the Dortmund mining authority, recorded increasing numbers in the mine workforces.[14] However, from the start of the 20th century, more and more professions in trade and crafts, such as tailors, cobblers, midwives, painters and hairdressers, could be found within the population of Ruhr Poles.[15] Nevertheless, the majority of the Ruhr Poles remained employed in mining and in the iron and heavy industries.

With the outbreak of the First World War, however, there was a fundamental change to the increasing economic upturn. The general wartime mobilisation meant that most of the people in the workforce that were the right age for military service were conscripted. As early as autumn 1914, the mines and heavy industry factories, in particular, were already complaining of an immense shortage of workers, but especially of skilled workers.[16] In his comprehensive monograph on the war work of the town, the local Bochum politician and civil servant in the Municipal Authority, Paul Küppers, delivered an almost euphoric description of the town’s work situation during the First World War, despite the adverse circumstances:

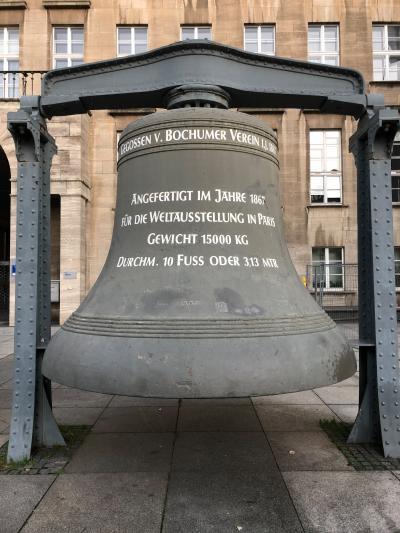

“A resounding hammer blow is mixed with the whirring of machinery to form the fundamental sound in the great symphony of work. (…) In pure chords, the Bochum cast steel bells announce their praise for the industriousness of the local people (…) And whilst the battle raged outside, the ranks of those that had stayed at home united in the Westphalian way, tough and strong, to deal with the tasks in which the battle at the front is to be conducted victoriously. There, the coal that gives power and light was produced with twice as much zeal; there, the iron was stretched, there, the steel was annealed and turned into weapons of destruction (…).“[17]

On the one hand, this almost poetic representation of the work ethic of the Bochum workers in the coal and steel industry indicates the enthusiasm for the war which prevailed amongst some of the German population whilst, on the other hand, the foreign workers, who made up a significant part of the labour force, are completely left out of the description. But it was the Polish workers, in particular, who made a significant contribution to keeping the mining and arms industry going during the First World War.[18]

It was for this reason that more than half a million more Poles came to the German Reich as civilian workers and prisoners of war during the war so that they could be deployed in the arms and industry sectors that were so important to the wartime economy.[19] It is, however, difficult to quantify the number of forced labourers from Poland because the statistical information is missing.[20]

The period of the First World War was marked by a (compulsory) recruitment of foreign workers, including a large number from Poland. After the end of the war, many of these Polish workers left the borders of the German Reich again. With the re-establishing of the Polish state in 1918, not only did the workers who had been recruited during the war return to their homeland, but the Ruhr Poles that had been settled in the Rhenish-Westphalian industrial region for decades also migrated out of the Ruhr area in increasing numbers. Whilst part of this population of Ruhr Poles moved on in the hope of better work opportunities in the French and Belgium coal districts, around 150,000 Ruhr Poles returned to their regions of origin which, after 1918, belonged once again to the Polish state.[21]

[14] cf. Rawe, Kai: „…wir werden sie schon zur Arbeit bringen!“. Ausländerbeschäftigung und Zwangsarbeit im Ruhrkohlenbergbau während des Ersten Weltkrieges, p. 47;

cf. Küppers, Paul: Die Kriegsarbeit der Stadt Bochum 1914-1918, p. 47.

[15] cf. Murzynowska, Krystyna: Die polnischen Erwerbsauswanderer im Ruhrgebiet während der Jahre 1880-1914, p. 59 f.

[16] cf. Rawe, Kai: „…wir werden sie schon zur Arbeit bringen!“. Ausländerbeschäftigung und Zwangsarbeit im Ruhrkohlenbergbau während des Ersten Weltkrieges, p. 47;

cf. Küppers, Paul: Die Kriegsarbeit der Stadt Bochum 1914-1918, p. 263.

[17] Küppers, Paul: Die Kriegsarbeit der Stadt Bochum 1914-1918, p. 301 f.

[18] cf. Molenda, Jan: Polnische Arbeiter im Ruhrgebiet während des Ersten Weltkrieges, p. 198.

[19] cf. Rawe, Kai: „…wir werden sie schon zur Arbeit bringen!“. Ausländerbeschäftigung und Zwangsarbeit im Ruhrkohlenbergbau während des Ersten Weltkrieges, p. 155 f.

[20] According to current research, it can be assumed that between 14,000 and 16,000 Polish civilian workers were deployed in the Ruhr mining industry alone during the First World War. It is not possible to reliably determine how many prisoners of war and forced labourers there were or where they were deployed because not all enterprises documented their deployment equally. Their number may, however, have been considerably higher than that of the civilian workers;

cf. Molenda, Jan: Polnische Arbeiter im Ruhrgebiet während des Ersten Weltkrieges, p. 185.

[21] cf. Skrabania, David: Die Ruhrpolen, in: https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/atlas-der-erinnerungsorte/die-ruhrpolen?page=9#body-top.