Bronisław Huberman: From child prodigy to resistance fighter against National Socialism

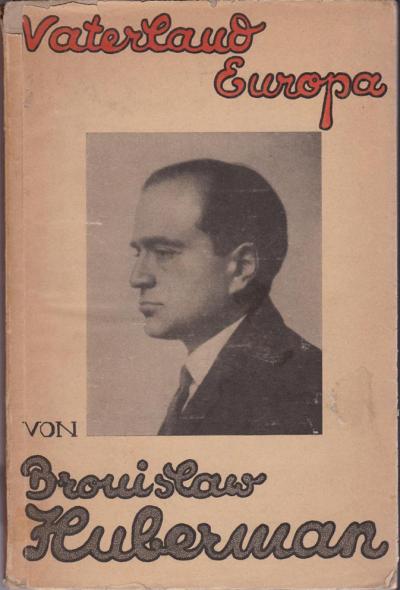

“I am a Pole, a Jew, a free artist and a pan-European. In each of these four character traits, I must see Hitlerism as my mortal enemy, I have to fight it with all the means at my disposal as my honour, my conscience, my reflection and my impulse dictate”, wrote Huberman on 18 October 1933 to a friend.[1] As a committed advocate of the pan-European idea propagated by the Japanese-Austrian philosopher Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi (1894-1972), Huberman himself had joined the fray by writing on this topic and had agitated publicly against Adolf Hitler since the 1930s. When his paper “Vaterland Europa” was published in Berlin in 1932, in October of that year he wrote about Hitler in the Neue Leipziger Zeitung whilst he was giving his last concerts in Germany: “The whole direction is wrong. His way is clearly the wrong way.”[2] When his friend, the director Wilhelm Furtwängler (1886-1954), approached him during the Johannes Brahms festival in Vienna in May 1933 and asked him to give a concert in Berlin during the coming season, Huberman declined. Furtwängler then wrote to him to invite him again, in response to which Huberman published a letter in the European and American daily newspapers in which he denounced the “race elite” prevailing in all cultural areas in Germany and the situation facing “those museum directors, conductors and music teachers” “who were dismissed on account of their Jewish heritage or differing political, or even simply apolitical attitude”; reasons, according to Huberman, “which immediately separate me from Germany” and which, despite the close relationship with his German friends and with German music, “created a “coercion of conscience to renounce Germany”.[3] Since this incident, if not before, the National Socialists’ official publications branded Huberman “a fanatical agitator against Germany”.[4]

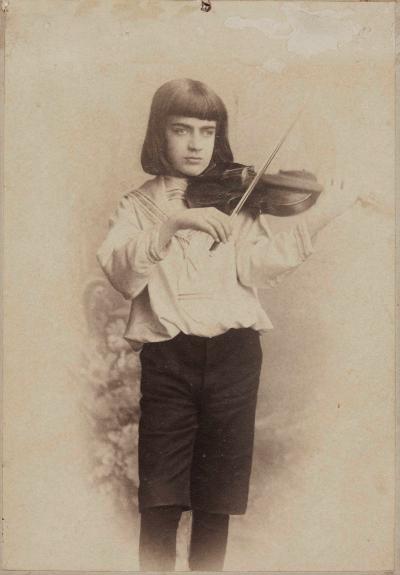

Bronisław Huberman was born in Częstochowa in the Russian-ruled Congress Poland on 19 December 1882 to the lawyer Jankiel Huberman and his wife Aleksandra, née Goldman. His father, who worked in a law firm, barely made enough money to provide for his wife and their three sons. From an early age, Bronisław demonstrated an extraordinary musical talent which his family encouraged despite their financial problems – Huberman is known to have said that his father was a passionate music lover. As a six-year old he had lessons at the Warsaw Conservatory with violinist Mieczysław Michałowicz (1872-post 1935), who trained him for two years, as well as with Izydor Lotto (1840-1927), Maurycy Rosen (1868?-after 1938) and the concertmaster of the Warsaw opera orchestra, Stanisław Barcewicz (1858-1929). The following year he performed in public for the first time. (Fig. 1) The family once again saved up to allow him to travel to Berlin at the age of nine so that he could play in front of the violinist, conductor and composer Joseph Joachim (1831-1907), the most influential musician of his era and the founding director of the Royal Academic Conservatory of Music in Berlin. Although Joachim hated “child prodigies”, he was won over by the boy’s talent and opened every door for him. In summer 1892, Bronisław gave a concert in the Austrian spa resorts, such as Karlsbad, Marienbad and Ischl, and had an audience with the Emperor in Vienna.

[1] Huberman writing to an acquaintance, letter dated 18 October 1933, Huberman Estate, Felicja Blumental Music Center, Tel-Aviv, cited from von der Lühe 1997 (see Literature), page 11

[2] Vaterland Europa. Bronislaw Huberman über den Weg zu Wohlstand, hohen Löhnen, Warenabsatz, Freiheit und Frieden in Europa, in: Neue Leipziger Zeitung, No. 297, 23.10.1932, cited from von der Lühe 1997 (see Literature), page 11

[3] Die Kunst im Dritten Reich. Hubermans Verzicht ..., Prager Tagblatt dated 13 September 1933 (see Sources)

[4] “Seit 1933 ein fanatischer Hetzer gegen Deutschland.” (Lexikon der Juden in der Musik 1940, see Anti-Semitic publications)

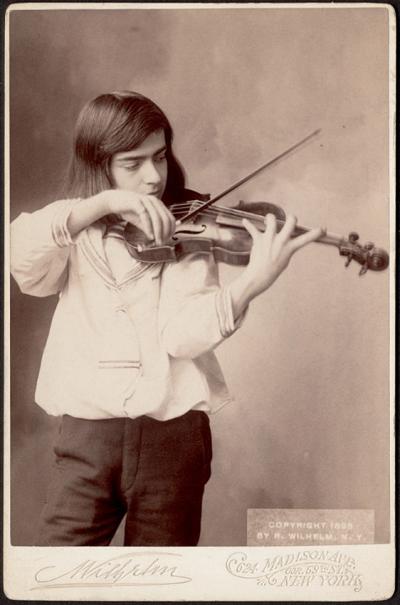

From the winter of 1892/93, a scholarship allowed him to study in Berlin under the music conservatory’s new director, the violinist Carl Markees (1865-1926), who hailed from Switzerland and who had been a student of Joachim, and to study under Charles Grigorowitsch, a student of the Polish violinist Henryk Wieniawski (1835-1880). The timetable, which Joachim drew up, also included lessons given by harmony and piano teachers and a violin course with Joachim himself. On Joachim’s initiative, Bronisław attended a concert given by the Polish pianist Artur Rubinstein (1887-1982) who he also had to play for. “I had my last […] lesson at the age of 12”, he would later write in his paper “Aus der Werkstatt des Virtuosen”.[5] From that point on, he gave concerts in the Netherlands, Belgium, Romania, Paris and London. It is said that the Polish magnate, entrepreneur and philanthropist Władysław Zamoyski (1853-1924) provided the young violinist with the funds to buy a Stradivarius violin, which was stolen twice, once in 1919 from the hotel and for the final time in 1936 from a cloakroom. In January 1895, (Fig. 2) he caused a sensation in Vienna as the escort of the Spanish opera diva Adelina Patti (1843-1919), with a solo concert in the Saal Bösendorfer[6] and with the Johannes Brahms violin concert, which he gave in the presence of the composer himself and in front of Anton Bruckner, Johann Strauß and Gustav Mahler in the Großen Musikvereinssaal.[7] One month later, he received an offer for a guaranteed fee of an incredible 100,000 Austrian guilders to undertake a concert tour through the United States[8], which he began in 1896 (Fig. 3) and which continued into the following year. A tour of Russia followed in winter 1897/98. In spring 1898, the fifteen-year-old was so exhausted that he withdrew from public life for four years. (Fig. 4)

From 1902, Huberman was once again performing on orchestra stages throughout Europe. On several occasions he played in Wroclaw, where he performed the solo works of Johann Sebastian Bach in 1906.[9] In January 1908, he gave a concert in Berlin with the Mozart Orchestra in the Mozartsaal of the Neues Schauspielhaus.[10] In July 1910, he married the actress Elsa Marguérite Galafrés (1879-1977) in London. The marriage, which produced one son, ended in divorce in 1913. In the two decades that followed, world tours took Huberman to the music capitals of Europe, to Russia, America, Australia and Southeast Asia.[11] During the First World War, he lived predominantly in Germany and undertook the occasional tour to Poland and Austria. On three days in April 1917, he performed all Beethoven’s sonatas for violin and piano in the Berlin Sing-Akademie with the pianist and composer Eugen d’Albert (1864-1932).[12] He also gave regular concerts with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra which, from 1922, was directed by Furtwängler.

[5] Huberman 1912 (see His Own Papers), page 21

[6] “ […] however, a surprising fire flowed from the small but yet so great violin virtuoso Bronislaw Hubermann [sic!] who is set for a happy and revered future. […] To us and to everyone else, the little Hubermann seemed more like a magician than a common or garden child prodigy […] he is in reality an exceptional talent who is already achieving great things and promises monumental things in the future.” (Deutsches Volksblatt, Vienna, 1 February 1895, morning edition, page 1, online resource: http://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=dvb&datum=18950201&query=%22Bronislaw%22+%22Huberman%22&ref=anno-search&seite=1). – On 20 March 1895, he once again gave a guest performance in the Saal Bösendorfer in Vienna where he performed the second violin concert by Henryk Wieniawski as well as other pieces (Saal Bösendorfer concert programme, sixth concert of 20 March 1895, online: http://bronislawhuberman.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/BN079_W.jpg)

[7] Platzer 2019 (see Literature), page 60

[8] “The young violin virtuoso Bronislaw Hubermann [sic!] was offered the enticing proposal to undertake a concert tour through America with a guaranteed return of 100,000 guilders. Hubermann’s mother and friends have not yet come to a decision.” (Neuigkeits-Welt-Blatt, Vienna, 22nd edition, No. 44, 22.2.1895, page 12, online resource: http://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=nwb&datum=18950222&seite=12&zoom=33&query=%22Bronislaw%22%2B%22Huberman%22&ref=anno-search) – Based on current tables, the sum of 100,000 guilders would have been worth 1 million euros today.

[9] Maria Zduniak: Bachrezeption in Breslau im 19. Jahrhundert, in: Alte Musik als ästhetische Gegenwart. Bach, Händel, Schütz, published by Dietrich Berke and Dorothee Hanemann, Kassel 1987, page 147 f.

[10] Concert programme from 22 January 1908, Ernst Henschel Collection, British Library, London, http://www.concertprogrammes.org.uk/html/search/verb/GetRecord/4575/

[11] Von der Lühe 1997 (see Literature), page 10; von der Lühe 2017 (see Online)

[12] Concert programmes from 19, 21 and 23 April 1917, Ernst Henschel Collection, British Library, London, http://www.concertprogrammes.org.uk/html/search/verb/GetRecord/4580/

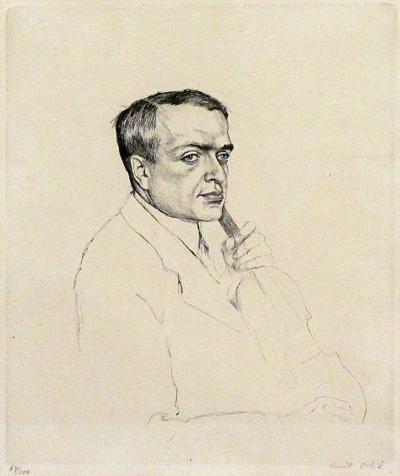

Huberman’s popularity in Germany is also captured in portraits created between 1915 and 1921 by the Berlin-based painters and illustrators Emil Orlik (1870-1932, Fig. 5), Lesser Ury (1861-1931, Fig. 6) and Eugen Spiro (1874-1972). For twelve years, from 1923 onwards, he was accompanied by the Berlin-based pianist Siegfried Schultze (1897-1989), including on concert tours around the world. Musically, Huberman devoted himself to the great violin concertos and sonatas, but he also had a particular passion for chamber music. He performed trios and quartets with Artur Schnabel (1882-1951), Pablo Casals (1876-1973) and Paul Hindemith (1895-1963). In November 1926, playing with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, he performed the premiere of the first violin concerto by the Polish composer Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937).

At the beginning of the 1920s, shaken by the political impact of the First World War, Huberman began to take an interest in global politics. Between 1920 and 1924 he spent the winter months on concert tours throughout the US where he believed that in the United States’ federal system with its economic prosperity, he had found the role model for a peaceful and united Europe. The impressions and experiences gained in North America led him to engage publicly for a federal and federally structured Europe, that is to say, a European federal state, which he referred to as Pan-Europe in line with the parlance of the day. From 1924, he became politically active in speeches and newspaper articles. He developed a close friendship with Coudenhove-Kalergi, who had been propagating the Pan-Europe idea since 1922 and had founded the Pan-Europe Union in 1924; a friendship which was to last until Huberman’s death. When an interview with Huberman appeared in the Berlin 8 Uhr-Abendblatt on 10 July 1925, Coudenhove-Kalergi wrote him a letter: “I am moved by the resoluteness with which you campaign for Pan-Europe.”[13] In his reply, Huberman was able to report that the Paris edition of the New York Herald “had reprinted the Berlin interview with a sensational layout.”[14] This was the start of a lively line of correspondence in which Huberman and Coudenhove-Kalergi discussed European policy issues, exchanged information and agreed travel plans so that they could arrange to meet.

In 1925, Huberman wrote a first paper on this issue entitled “Mein Weg zu Paneuropa”, which Coudenhove-Kalergi published in the second edition of the magazine Paneuropa and which evidently also appeared as a special edition.[15] As Huberman saw it, the priorities were the economic and health and welfare considerations that he had seen realised in the American Fordism of the 1920s, i.e. in the industrial production of goods using division of labour within a large, unified economic area. He believed that Europe was hampering itself by its particularism determined by customs borders. In the American role model, Huberman saw the realisation of a high level of economic productivity, relative prosperity in broad sectors of the population and a distinct patronage by individual affluent citizens that benefited education and culture, “an assessment, which – especially from today’s perspective – may appear idealistic or even marked by politically naive enthusiasm”, stated the political scientist Hans-Wolfgang Platzer (*1953), but “amongst contemporary US observers did not in any way occupy an outsider position”.[16]

[13] Letter from Coudenhove-Kalergi to Huberman dated 10 July 1925, Huberman Estate (see Note 1), cited from Platzer 2019 (see Literature), page 122

[14] Letter from Huberman to Coudenhove-Kalergi dated 21 July 1925, ibid

[15] For bibliographic information see His Own Papers

[16] Platzer 2019 (see Literature), page 80 f.

In 1926, wealthy benefactors provided Huberman with an apartment in Vienna in the state-administered Schloss Hetzendorf, where he then settled for the next decade. At this time, Huberman was already known as “one of the most interesting and intellectual minds of our time”, as the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung reported on 2 February 1926: “Thanks to the authority bestowed upon him by his notability, the artist has done an incredible amount for the Pan-Europe movement in particular, and what’s more, he has used his truly creative ideas to point this young movement in new directions.[17] Huberman was one of the main speakers at the first Pan-Europe Congress, which was held in the great hall of the Konzerthaus in Vienna in October 1926, had two thousand participants and played out in front of six hundred representatives from national and international media. In his speech, which was again printed in his second paper “Vaterland Europa” (Fig. 7) published in Berlin in 1932, he set out the integration goals and processes necessary for European unification, such as customs and monetary union, legislative alignment, setting up a supranational army, protection of minorities and the invisibility of borders. Whilst the German envoy in Vienna, Count Hugo Lerchenfeld (1871-1944), made disparaging comments in his report to the Foreign Minister in Berlin, Hugo Stresemann (1878-1929), the Frankfurter Zeitung wrote: “ […] we were surprised to hear him talking instead of playing the violin. But that is what made you take it seriously – that a great artist […] feels the urge to get involved with politics. […] Old Europe must be in great distress if she does not even leave the musicians in peace.”[18] The congress ended with a violin solo from Huberman.[19]

Meanwhile, Huberman’s international concert activities had helped him to achieve great wealth and this allowed him to support young musicians and to donate takings from his concerts as well as his own money to charitable causes. He donated funds to the Vienna National Library and in 1928 to the public purchase of an estate in Żelazowa Wola to the west of Warsaw where Chopin’s birthplace was to be found and for which money had been collected throughout Poland. He supported contemporary composers by performing their works. With Poland being represented at the first Pan-Europe Congress by Władysław Landau, a socialist and delegate of the League of Nations leagues and a leader of the Polish students,[20] Huberman initiated and supported the founding of a national Pan-Europe committee in Poland. This was joined by intellectuals, left-wing activists and young academics, including pacifists and friends of the League of Nations.[21]

[17] Newspaper article in the Huberman Estate (see Note 1), cited from Platzer 2019 (see Literature), page 61 f.

[18] Frankfurter Zeitung dated 9 October 1926, Huberman Estate (see Note 1), cited from Platzer 2019 (see Literature), page 125

[19] Neue Freie Presse, Vienna, No. 22294, dated 7 October 1926, morning paper, page 3, online resource: http://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=nfp&datum=19261007&seite=3&zoom=33&query=%22Huberman%22&ref=anno-search

[20] Landau spoke out in favour of the German-Polish friendship: “The youth of Germany and Poland must find itself; it is a disgrace of the twentieth century that we Poles and Germans do not have the closest of relationships, that we still have to fight a customs war and that we are still fighting an internal war in our hearts. I beg of you not to believe the rumours that Poland wants war.” (Neue Freie Presse dated 7 October 1926, ibid). Compare also Dagmara Jajeśniak-Quast: Polish Economic Circles and the Question of the Common European Market After World War I = Individual publications of the Deutsche Historische Institut Warsaw, Volume 23, Warsaw 2010, page 136, digital version: https://perspectivia.net/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/ploneimport_derivate_00011467/jajesniak-quast_circles.pdf

[21] Platzer 2019 (see Literature), page 127

As well as addressing economic and political issues, Huberman’s papers and speeches also dealt extensively with cultural issues. What today’s debates on integration still refer to as the “cultural identity of Europe”, Huberman dealt with under the term a common “mentality”.[22] He substantiated the fact that a “Pan-Europe of the mentality” actually existed by giving examples from Europe’s shared cultural history and from his own experiences: “During the war, the German theatre under the leadership of Max Reinhardt undertook state-funded propaganda trips to neutral countries with plays by the “enemy” national Maxim Gorki, whilst Puccini was performed in State Theatres in Vienna and Budapest as the battles of Isonzo were raging; and Wagner and Brahms were performed at concerts in Paris; I, the Pole, despite my official status as an enemy national, performed the concerto suite, the masterpiece by the Russian Taneieff in Berlin in 1917, and in Paris in the first year after the ceasefire, I played the sonatas of the German Richard Strauss. […] There was never a time, even during the worst German-Polish hate speech, in which German artists would not have been enthusiastically welcomed in Poland and in which Polish artists would not have been enthusiastically welcomed in Germany.”[23]

But as well as the shared cultural heritage, Huberman was also at pains to stress the diversity of national cultures to which Europe owed “the Ninth Symphony, Faust, the Sistine Madonna, the ballads of Chopin and so on”, but which, because of the restrictive cultural education which favoured the rich and which prevailed throughout Europe, only a dwindling minority would actually get to enjoy: “You see it happening again and again in Europe: This Hamlet, this Ninth Symphony does not gather its worthy and needy listeners around it, instead there is but that small heap that, during the periodically recurring clash of European populations, escaped financial ruin thanks to a lucky coincidence. A culture, which has as its prerequisite the mutual mangling of nations, as a result of which it is inaccessible to 99 out of 100 Europeans and thus remains a pure class culture”.[24] Huberman also devoted himself to the issue of language and recommended that the respective country language and three world languages be used on equal terms.

[22] Ibid, page 113

[23] Huberman 1925 (see His Own Papers), page 20

[24] Huberman 1932 (see His Own Papers), page 44 f.

As a result of his years of engagement for the Pan-European idea and his own political convictions, Huberman, who travelled through numerous German towns during his concert tours, had a keen sense of the political developments there. In Berlin, Huberman was one of the few soloists “who was able to fill the philharmonic hall several times in one season with a solo evening”,[25] recalled Dr Berta Geissmar, Furtwängler’s executive secretary and “right hand”.[26] Huberman could not escape the anti-Semitism that had been on the rise since the beginning of the world financial crisis in October 1929 among the petty bourgeoisie in Germany, the German National People’s Party and, of course, the National Socialists. The hostile attitude towards Jews became almost pogrom-like during the attack on the Berlin Warenhaus Wertheim by supporters of the NSDAP, which took place on the occasion of the opening of the Reichstag on 13 October 1930, and during the anti-Semitic attacks by the SA during the Kurfürstendamm riot in September 1931. In the previously cited article from October 1932 in the Neue Leipziger Zeitung, Huberman noted with concern that lately people in Germany “are enthusiastically worshipping the confinement, are wanting to remain huddled together within limited bounds; that is the new religion of one Adolf Hitler, who, although a foreigner himself until recently, is bubbling over with ‘nothing other than being German’ and has written class hatred and ethnic hatred on his flag.”[27]

The fact that Huberman’s fears were justified was proven soon after power was transferred to the National Socialists. On 1 April 1933, they called for the first time for Jewish businesses, department stores, banks, doctors’ practices, lawyers and notaries to be boycotted and a few days later, with the enactment of the Law for the restoration of the professional civil service, started to remove Jewish civil servants from the civil service. Furtwängler, as reported by Geissmar, who was herself a Jew, always declared publicly and “unequivocally that the German music scene would soon be completely paralysed if it were to be regulated based on racial considerations”.[28] A large number of the great soloists and conductors were Jews as were many of the outstanding orchestra musicians. Jewish lawyers, doctors, academics and financiers, who themselves made music and supported the music industry, made up a significant portion of the audience. During the first concert tour of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in spring 1933 after Hitler came to power, there were open conflicts with the Nazis among local musicians, in the audience and at receptions in various German cities, such as Mannheim and Baden-Baden. In Paris, Marseille and Lyon, the orchestra met with hostility and threats of boycott because of the German Jewish policy, although Furtwängler was repeatedly able to demonstrate that Jews were not marginalised in his orchestra. However, numerous conversations between Furtwängler, Hitler, Reich propaganda minister Goebbels and “more minor party leaders“, in which the orchestra director warned “of the disastrous consequences of their race and party policies on Germany’s cultural life”,[29] did not have any lasting impact.

[25] Geissmar 1985 (see Literature), page 113

[26] Fred. K. Prieberg: Berta Geissmar – Versuch einer Vergegenwärtigung (1985), in: Berta Geissmar 1985 (see Literature), page II

[27] Huberman in the Neue Leipziger Zeitung dated 23 October 1932 (see Note 2), cited from von der Lühe 2004 (see Literature), page 70

[28] Geissmar 1985 (see Literature), page 77

[29] Ibid, page 84

In May 1933, the Berliner Philharmonic Orchestra travelled to concerts in Geneva, Zurich and Basel and undertook a smaller tour through German towns to Vienna where the German Brahms Society and the Vienna Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde were putting on the Eighth Johannes Brahms Festival to mark the occasion of the composer’s birthday. Furtwängler directed the double concerto for violins and cello with Huberman and Pablo Casals as soloists. Whilst Schnabel performed as soloist in the second piano concerto, Huberman, Hindemith and Schnabel created the chamber music section. Because Furtwängler had to prepare his programmes for the forthcoming Berlin concert season in winter 1933/34, he intended to approach the Hitler government and ask for a special permit to allow some of the international music greats to perform. To do this, he called upon Huberman to commit and to actively participate. In a letter, Huberman reported: “During the Brahms Festival in Vienna, Furtwängler spent hours trying to convince me to give my consent to appear in case he could get the declaration of new directives that he had in mind from the government. I rejected this unreasonable demand as being beneath my dignity […].”[30] At this point, Huberman also provided a public statement.

Whilst Furtwängler had already spoken out in an open letter to Goebbels about outstanding artists remaining in German culture, such as “Walter, Klemperer, Reinhard[t] etc.,[31] a letter that Huberman knew very well, Furtwängler then presented his view once again “of a moderate entity close to the Reich Chancellery […] and his proposals were approved.”[32] On the strength of this, Furtwängler addressed personal invitations in June to Casals, Cortot, the Polish pianist Józef Hofmann, Huberman, Kreisler, Menuhin, Schnabel, the cellist Gregor Piatigorsky and the violin virtuoso Jacques Thibaud, however, they all declined. As Geissmar recalled, the soloists “in their response unanimously held the view that, despite Furtwängler’s personal efforts, the German music scene had been politicised – and all of them, Aryans and non-Aryans alike, refused to avail themselves of privileges that were only being granted to them because of their international reputation. They declared categorically that they would not perform in Germany until the same rights applied to all.”[33]

[30] Letter from Huberman to “Bn.” dated 18 October 1933, Huberman Estate (see Note 1), cited from von der Lühe 2004 (see Literature), page 71

[31] Goebbels über die Kunst. Correspondence with Furtwängler, in: Vossische Zeitung, No. 171, dated 11 April 1933, morning edition, page 3, online resource: http://zefys.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/index.php?id=dfg-viewer&set%5Bimage%5D=3&set%5Bzoom%5D=min&set%5Bdebug%5D=0&set%5Bdouble%5D=0&set%5Bmets%5D=http%3A%2F%2Fcontent.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de%2Fzefys%2FSNP27112366-19330411-0-0-0-0.xml

[32] Geissmar 1985 (see Literature), page 85. – This “entity” was obviously the Prussian minister of cultural affairs Bernhard Rust, member of the NSDAP, the Prussian State Parliament and the Reichstag, who headed up the Reich Ministry for Science, Education and Public Education from 1934 to 1945. Rust had convened a commission to regulate the future of the German music industry, a commission which comprised Furtwängler, Max von Schilling, Wilhelm Backhaus and Georg Kulenkampff and which, in the future, was to review “the programmes of all the public concert associations”. An exposé published on this subject stated, “that German artists, who are called upon to support and maintain a German music industry, have to be used first and foremost. It must, however, be pointed out that in music, as in any art form, the performance must always remain the crucial factor, with other considerations having to take a step back in favour of the principle of performance, if necessary.” (Prager Tagblatt dated 13 September 1938, Fig. 8). Furtwängler evidently considered the last sentence to be a guarantee that would also allow him to engage prominent foreign (or non-Aryan) artists in accordance with the principle of performance.

[33] Ibid

In a detailed letter dated 10 July 1933, Huberman responded to his “dear friend” Furtwängler and the next day asked if he may be allowed to publish this response in the international press. Although Furtwängler did not agree to this (“the consequence would surely be that you […] would perhaps no longer by allowed to perform in Germany at all”[34]), Huberman sent copies of his letter to Louis P. Lochner (1887-1975), the head of the Berlin office of the Associated Press, in the hope that the letter would be published in the New York Times. Lochner, who was to stay in Marienbad ten days later, managed to get the public version of the letter published in the Prager Tagblatt on 13 September 1933 (Fig. 8). The next day, an English translation appeared in the context of an article in the New York Times by the American journalist Frederick T. Birchall (1871-1955) under the headline “Huberman Bars German Concerts”.[35]

In his letter, not only did Huberman appeal to the conductor Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957), who had recently declined to participate at the Bayreuth Festival because of the anti-Jewish and anti-foreigner sentiment in Germany, he also expressed his admiration for Furtwängler “for the fearlessness, tenacity, sense of responsibility and tenaciousness” with which he had carried out his “campaign that he had begun in April to rescue concert life from the threat of annihilation by the race cleansers”. However, Huberman felt that the assurances negotiated with Reich Minister Rust about select artists participating in the German music scene based on the “principle of performance”, which the Prager Tagblatt cited in detail, could “not be considered a sufficient basis” for him “to be part of the German music scene again”. The “selection principle” smacks of the intention “to continue to apply the unthinkable, race selection, to all other areas of culture.” Whilst there was to be an exemption for music, museum directors, researchers and teachers would continue to be marginalised. The “few foreign or Jewish musicians called upon to participate” were only there to “be paraded before the whole world to show that all is well with culture in Germany. In reality, however, German thoroughness would keep on applying new definitions about racial purity to immature art lovers, schools, laboratories etc.”

[34] Furtwängler to Huberman dated 27 July 1933, Huberman Estate (see Note 1), cited from von der Lühe 2004 (see Literature), page 72

[35] Complete bibliography for both newspaper articles, see under Sources.

Huberman wrote to Furtwängler that his separation from Germany left him with a deep “ache as a friend of my German friends, as an interpreter of German music who sorely misses the resonance of his German audience”, then went on to pass judgement on Furtwängler in a letter written in October 1933: “This mixture of idealism, opportunism, vanity and cultural attitude […], from positioning his handful of Jewish orchestra members in the first stands at the Paris concert hall right up to accepting an honour from a Prussian State Council; that’s just going too far!“[36] Huberman never set foot on German soil again. From 1934, he directed a master class at the state-run Vienna Music Academy for two years. In July/August 1935, as the Wiener Zeitung reported, the Reich Chamber of Music in Berlin asked the pianist Siegfried Schultze to cut his ties to Huberman. Huberman’s “anti-German” conduct was given as the reason.[37]

In March 1936, Huberman wrote an “Open letter to German intellectuals” which was published in The Manchester Guardian newspaper in English.[38] In it, Huberman once again referred to his letter to Furtwängler writing: “Two and a half years have now passed, countless people have been thrown in concentration camps, in prison, chased out of the country, sent to their death by murder or suicide […] before the whole world, I accuse you, German intellectuals, you non-Nazis, of being the real culprits in all the Nazi crimes, in this mournful downfall of a superior people that shames and threatens our entire white race. […] German spiritual leaders with the international importance and freedom of movement of a Richard Strauss, Furtwängler, Gerhart Hauptmann, Werner Krauß, Kolbe, Sauerbruch, Eugen Fischer, Planck among others, who until yesterday represented the German conscience, the German genius […], from the very start have reacted in no other way to this attack on mankind’s most sacred assets than to flirt, make deals, cooperate. Germany, the people of poets and philosophers, the world, not just the hostile world, your friends wait in dismay for a word of liberation!”[39]

[36] Letter from Huberman to “Bn.” dated 18 October 1933, Huberman Estate (see Note 1), cited from von der Lühe 2004 (see Literature), page 74

[37] Theater und Kunst. Die Reichsmusikkammer gegen Huberman, in: Wiener Zeitung, published by the Federal Administration, 232nd edition, No. 211 dated 2 August 1935, page 8, online resource: http://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=wrz&datum=19350802&seite=8&zoom=25

[38] Typed manuscript in German in the Huberman Estate (see Note 1). In 1944, when Huberman was being awarded an honorary doctorate by the Jewish Institute of Religion in New York, the German version of his letter was published again, this time in the German-Jewish newspaper for people in exile entitled Aufbau from the New York-based New World Club (bibliographic information and online resource see Sources).

[39] Cited from the 1944 version (see Note 38)

Around the same time, Huberman set up the Palestine Orchestra which he began as an effective weapon against the Nazi regime. However, the history to this dates back two years earlier. At the beginning of 1934, Huberman was on a tour through Palestine where he had given his first guest performance in 1929. The recent series of concerts comprised a total of twelve sold-out performances, which were followed by several “concerts for workers”, that is, performances with a reduced entry price for the poorer strata of the population. In Tel Aviv he appeared with an orchestra that had been founded in 1933. Its members had been living in Palestine since the 1920s and had recently started to welcome musicians who had emigrated from Europe.[40] Huberman commented that the woodwind and brass sections in the orchestra needed to be reorganised and made the concert takings available to engage new players from Europe. In 1935, when it transpired that his plans did not align with the objectives of the current initiators, he developed plans for his own orchestra which was to be financed with the aid of Jewish patrons in Europe and the US through an international orchestra trust. At the end of 1935, he entrusted the economist Salo B. Lewertoff (1901-1965), who had emigrated from Cologne and was the former head of the Cologne chapter of the International Society for Contemporary Music,[41] with the orchestra’s management and with the position of general secretary.

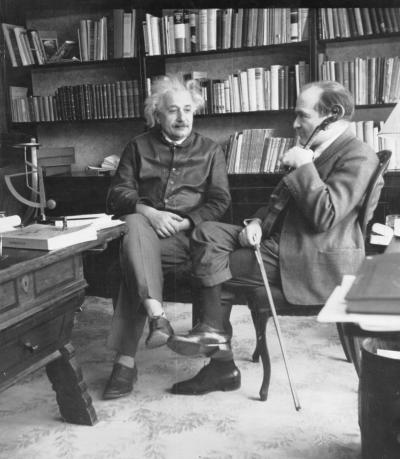

From February to April 1936, Huberman undertook a concert tour through the US. On 9 February, the New York Times reported under the heading “Orchestra of Exiles”: “Bronislaw Huberman, the Polish violinist, has reported that the first symphony orchestra in Palestine is to be created. The orchestra will have 65 musicians. It will be formed from outstanding German musicians who have been denied the right to play in their own country, and from other prominent European musicians.”[42] Huberman managed to rake together the basic capital to found the orchestra by holding forty-two benefit concerts right across the United States, which he completed in sixty days. In interviews and speeches, he stressed that his main motivation was to rescue Jewish musicians and their families from the National Socialists. He also managed to get artists, scientists and financially powerful groups interested in the founding of the orchestra. On 30 March 1936, the physicist Albert Einstein (1879-1955, Fig. 9) held a dinner at the Waldorf Astoria to benefit Huberman’s project and supported the campaign with letters to personalities from public life.[43] Toscanini made a spontaneous statement that he was prepared to direct the inaugural concerts of the new orchestra in Tel Aviv, Haifa and Jerusalem as well as some concerts in Egypt. This commitment, which was also published by the New York Times, led to financial assurances from numerous Jewish personalities which meant that the future orchestra’s existence was secured for three years.

[40] Von der Lühe 1993 (see Literature), page 1046 ff.

[41] For a biography of Salo(mon, Shlomo) Bernhard Lewertoff, who was born the son of a merchant in Höxter in 1901, compare von der Lühe 1998 (see Literature), page 72

[42] The Week’s News and Comment Concerning Music. Orchestra of Exiles, in: The New York Times dated 9 February 1936, Section X, page 7, preview see online : https://www.nytimes.com/1936/02/09/archives/orchestra-of-exiles.html?searchResultPosition=2

[43] Von der Lühe 1998 (see Literature), page 78 f.

Huberman then selected the first musicians for the orchestra whilst on concert tours in Europe by auditioning individual musicians in various cities, such as Warsaw, Vienna and Basel. The most important criterion for Huberman was the outstanding quality of the instrumentalists, particularly since the benchmark for the orchestra could not be set high enough now that Toscanini had been announced as the conductor. He was supported in selecting players and organising auditions by colleagues and conductors with whom he was friends, including the Austrian-Hungarian conductor Georg Szell (1897-1970), head of the Scottish National Orchestra at the time. In Berlin, the conductor Hans-Wilhelm (William) Steinberg (1899-1978), who was the general music director and subsequently orchestra conductor of the Kulturbund deutscher Juden in Frankfurt am Main until 1933, held the auditions in the Hotel Fürstenhof, a traditional luxury hotel in Potsdamer Platz. In the same year, Steinberg emigrated to Palestine and became the principal conductor of the Palestine Orchestra.

The salary expectations and visions for the future of those musicians who were living in Germany did not always match the opportunities available in Palestine or the living conditions there and this meant that many of Huberman’s preferred candidates declined.[44] Most of the musicians arriving from Germany came from the orchestras of the Jüdischer Kulturbund in Frankfurt and Berlin. They included, for example, the trombonist Heinrich Schiefer (1906-2006), who was born the son of Polish parents in Berlin-Kreuzbert. He had worked in Berlin as a jazz musician, performed at various engagements in the Netherlands and in Switzerland and had been declared stateless in Germany in 1935. Also from Berlin was the horn player Horst Salomon (*1913), a passionate amateur wrestler and member of the Zionist sports club Bar Kochba, whose musical abilities were so well known in various orchestras and theatres in Berlin that he did not need to audition for Steinberg and Huberman. Schiefer and Salomon, who were good friends, emigrated to Palestine together.[45]

In the neighbouring countries, more Jewish musicians felt ready to emigrate because of the growing anti-Semitism, the difficult economic conditions and the increased intimidation and threat of war emanating from Germany. In Warsaw, Huberman, helped by the leader of the second violin section, Jacob Surowicz, had prepared the auditions for members of the philharmonic orchestra there. In the end, he hired the violinists Mieczysław Fliederbaum, who emigrated to Palestine with his wife and son, the cellist Chaim Bodenstein with his wife, the brothers Alfred, Bolesław and Bronisław Ginsberg, who played violin, cello and timpani, with their families, their father the viola player Pesach Ginsberg (Ginzburg) and his wife, the trombonist Michał Podemski with his family, the viola player Marek Rak and his wife, the violinist Moszek Styglitz with his wife who lived in Belgium and the bassoonist Leon Szulc and his cousin, the horn player Bronisław Szulc,[46] as well as Surowicz himself with his family.[47] Some musicians did not meet Huberman’s quality standards and countless others turned to him for help. For these people, Huberman's international connections helped him organise their emigration to other countries, such as England.

By summer 1936, Huberman had hired more than fifty musicians from Poland, Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, the Baltic States and Italy and had managed to help them and their families emigrate to Palestine. British and Jewish personalities in Tel Aviv took care of the difficult business of obtaining immigration certificates, a task which had been made more difficult by the start of the Arab revolt in April 1936 and the partitioning of Palestine by the British mandatory power. Even the Jewish Agency, the public representative of the Jews in Palestine which was responsible for the immigration permits, and the Zionist administration in Jerusalem expressed a number of concerns because the “Huberman musicians” were taking jobs away from colleagues who based in Palestine. On top of this, the immigration certificates were, in principle, reserved for agricultural workers and tradespeople who were to play their part in building a Jewish Palestine.[48] Huberman also took musicians from the previous orchestra in Tel Aviv and welcomed them into the new Palestine Orchestra which, in the end, had seventy-three members.

[46] Compare the biography of Bronisław Szulc in this portal, https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/lexikon/szulc-bronislaw

[47] Von der Lühe 1998 (see Literature), page 100

[48] Von der Lühe 1993 (see Literature), page 1048

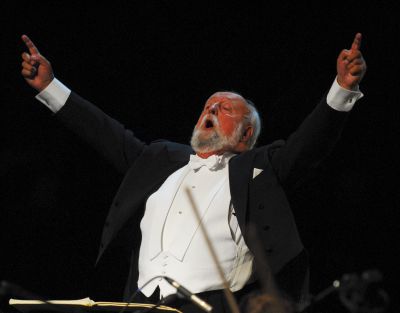

The final line-up, however, was in a constant state of flux because Huberman filled the various orchestra positions with different people depending on future conductors, and some of the musicians returned to Europe because of the climate and the problematic living conditions in Palestine or moved on to other continents, such as North and South America. Sometimes the musicians’ life plans changed altogether.[49] Huberman himself gave up his residence in Vienna in the late summer of 1936, presumably because of the political developments there and the anti-Semitism which was becoming ever more threatening. He initially went to Italy before settling in Switzerland in 1938. The start of the concert season in Palestine, which was planned for autumn 1936, was delayed because of the Arab revolt. The last musicians and their families did not arrive in Palestine, individually and in groups, until November. Steinberg, who had consulted with Toscanini in Italy about the work, took over the rehearsals. Toscanini, who the orchestra musicians considered the most feared conductor of his time, arrived in Tel Aviv on 20 December 1936 after travelling by rail and plane from Milan via Brindisi, Athens and Alexandria. On the whole, he was happy with the rehearsals, but criticised the typical “German” way of playing: “Don’t play me any Prussian marches. […] Play with a light touch, like the French or the Italians”, he demanded of the orchestra (Fig. 10).[50]

The inaugural concert on 26 December 1936 was filled to the rafters with more than two thousand five hundred people in the audience. The programme included an overture by Rossini, the second symphony by Brahms, Schubert’s “Unfinished”, Nocturne and Scherzo from Mendelssohn’s “Summer Night’s Dream”, and the “Oberon” overture by Carl Maria von Weber. The concert was repeated several times in Tel Aviv, Haifa and Jerusalem and was transmitted by Jerusalem radio via Cairo and London to the US. By 5 January, fifteen thousand visitors had experienced the ten concerts, shows for workers, and public rehearsals. From 7 to 12 January 1937, Toscanini and the orchestra went on tour to Cairo and Alexandria. Huberman deliberately did not take part in these concerts so that the orchestra could take centre stage.[51]

[49] Compare in this portal (https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/lexikon/broches-raphael) the biography of the Polish-Jewish violinist Raphael Broches (1906-1941?) who came to Palestine in December 1936 from Hamburg to take up his place in the orchestra but returned to Germany in the January to finish his musicological doctorate. Broches was presumably deported from the Warsaw Ghetto to the Treblinka concentration camp in 1941 and murdered there.

[50] Memories of Heinrich Schiefler, in: 40 Years. The Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Tel Aviv 1976

[51] For the Toscanini concerts and the first concert season, compare von der Lühe 1993 (see Literature), page 1046, and von der Lühe 1998 (see Literature), page 156-160

Huberman did, however, intend to appear with the Palestine Orchestra in the following concert season, in autumn 1937. But when his plane crash landed on the island of Sumatra during a tour of Australia and Asia at the beginning of October 1937, Huberman suffered such severe injuries to both arms that he was unable to appear. He did not return to making music with the orchestra that he had founded until December 1938 when he appeared under the leadership of the Hungarian conductor Eugen Szenkar (1891-1977). Szenkar was also a victim of the political situation in Europe. In 1924, the principal conductor of the Cologne Opera had been removed from office by the National Socialists and had fled to Vienna. Invited to Moscow in 1934, where he had led the State Philharmonic Orchestra since that time, he was expelled from Russia in 1937 during the Stalinist purges. In 1938/39, he led the fourth subscription concerts of the Palestine Orchestra and four concerts in Cairo and Alexandria during the second Egypt tour.

Huberman also carried out guest appearances in numerous European cities. In February and March 1940, he travelled to be “his” orchestra for the last time and together they gave concerts in Palestine and Egypt. The course of the war meant that he was unable to return to Switzerland from a concert tour to South Africa, travelling instead to the US in August 1940. There he continued to give concerts until summer 1945. After the end of the Second World War, he fulfilled his concert obligations and completed tours in Europe, the US and Cuba but became so seriously ill after his last public concert in Zurich in April 1946 that he was no longer able to perform. He died on 16 June 1947 in his house in Corsier in the Swiss canton of Waadt. Thanks to his founding of the orchestra, an estimated six hundred people were able to be saved from persecution and death between 1936 and 1939.[52]

After its frantic start, the Palestine Orchestra enjoyed great popularity in Palestine and undertook a tour to Egypt every year. However, when the Second World War broke out, it ran into financial difficulties because foreign conductors stayed away and the local orchestra leaders were unable to convince musicians or audiences to support it. Inevitably, the financial donations from Europe failed to materialise. The tense economic situation meant that most of the orchestra members also had to play in cafés and hotels. Nevertheless, in 1942 and 1943 more than two hundred concerts were still being held per season. The orchestra also released itself from Huberman’s influence. His absence and subsequent ill health meant that he was unable to look after it any more anyway. The funding system of the international trust gradually collapsed because European and American patrons withdrew their patronage. In 1946, the orchestra committee elected by the musicians decided on a new organisational form financed by municipal and state institutions in Palestine. After the state of Israel was created in May 1948, the orchestra was definitively renamed the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra[53] at the beginning of the 1948/49 concert season and is today considered one of the leading ensembles in the world.

Axel Feuß, September 2020

[52] Von der Lühe 2017 (see Online). The documentary “Orchestra of Exiles“ (2012, see Media) puts that number at around 1,000 Jews who were rescued (min 1:21:05).

[53] Von der Lühe 1993 (see Literature), page 1051 f.

Writings by Bronisław Huberman:

Aus der Werkstatt des Virtuosen = Aus der eigenen Werkstatt – Vortragszyklus im Wiener Volksbildungsverein, Leipzig, Vienna 1912

Mein Weg zu Paneuropa, in: Paneuropa, published by R.N. Coudenhove-Kalergi, second Edition, Issue 5, Vienna, Leipzig 1925, page 7-34 (also as special edition: Vienna 1925)

Vaterland Europa, Berlin 1932

Sources:

Die Kunst im Dritten Reich. Hubermans Verzicht. Ein Briefwechsel mit Wilhelm Furtwängler, in: Prager Tagblatt, 58th Edition, No. 214, dated September 13, 1933, page 3, Online resource: http://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=ptb&datum=19330913&seite=3&zoom=33

Frederick T. Birchall: Huberman Bars German Concerts. Violinist Rejects an Appeal by Furtwaengler to Play With Berlin Philharmonic Again. Stresses Nazi Race Bias. Declares That the Elementary Preconditions of European Culture Are at Stake, in: New York Times dated 14 September 1933, page 11

Offener Brief an die deutschen Intellektuellen. Von Bronislaw Huberman [Open Letter to German Intellectuals, in: The Manchester Guardian dated 7 March 1936], in: Aufbau / Reconstruction, published weekly by The New World Club, New York City, Volume 10, No. 4 dated 28 January 1944, page 17, online resource: https://archive.org/stream/aufbau101944germ#page/n57/mode/1up

32 newspaper articles (mainly reviews and interviews) on Bronislaw Huberman from 1933-1947, Walter A. Berendsohn-Research Centre for German Exile Literature, Hamburg State and University Library Carl von Ossietzky, Hamburg, Signature PWJ I 1405

Anti-Semitic publications:

Brückner-Rock. Judentum und Musik mit dem ABC jüdischer und nichtarischer Musikbeflissener, begründet von H. Brückner und C.M. Rock, edited and expanded by Hans Brückner, Third Edition, Munich 1938, page 129

Lexikon der Juden in der Musik. Mit einem Titelverzeichnis jüdischer Werke. Compiled on behalf of the Reich leadership of the NSDAP based on official documents checked by the party, edited by Theo Stengel and Herbert Gerigk = Publications of the Institute of the NSDAP for the Investigation of the Jewish Question, Volume 2, Berlin 1940, column 117

Literature:

Huberman, Bronislav (sic!), in: Österreichisches biographisches Lexikon 1815-1950, volume 2, instalment 10, Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1959, page 445 f.

Riemann Musik-Lexikon, Personenteil A-K, Mainz 1959, page 833

Władysław Hordyński: Huberman (Hubermann) Bronisław, in: Polski słownik biograficzny, volume 10, page 77 f., Wrocław and others 1962-64

Huberman, Bronislaw, in: Biographisches Handbuch der deutschsprachigen Emigration nach 1933 / International Biographical Dictionary of Central European Emigrés 1933-1945, München and others 1983, page 544 f., digital version: https://www.degruyter.com/viewbooktoc/product/53124

Berta Geissmar: Musik im Schatten der Politik (1945). Foreword and comments by Fred K. Prieberg, 4th edition, Zurich 1985

Barbara von der Lühe: Vom Orchester der Einwanderer zu einer nationalen Musikinstitution Israels. Die ersten Jahre des Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, in: Das Orchester. Magazine for Orchestra Culture and Radio Choirs, 41st edition, Mainz, October 1993, pages 1046-1053

Barbara von der Lühe: “Ich bin Pole, Jude, freier Künstler und Paneuropäer.” The violinist Bronislaw Huberman, in: Das Orchester. Zeitschrift für Orchesterkultur und Rundfunk-Chorwesen, 45th edition, Issue 10, Mainz 1997, pages 8-13

Barbara von der Lühe: Die Musik war unsere Rettung. Die deutschsprachigen Gründungsmitglieder des Palestine Orchestra. With a foreword by Ignatz Bubis = Series of scientific essays of the Leo-Baeck-Instituts, Vol. 58, Tübingen 1998

Piotr Szalsza: Bronisław Huberman. Czyli Pasje i namiętności zapomnianego geniusza. Monografia muzyczna skrzypka-wirtuoza, Częstochowa: Muzeum Częstochowskie, 2001

Friedemann Eichhorn: Huberman, Bronisław, in: Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Allgemeine Enzyklopädie der Musik, Personenteil, Vol. 9, Kassel 2002, column 452 f.

Marian Fuks: Doskonałość i uduchowienie. Bronisław Huberman (1882-1947), in: Księga sławnych muzyków pochodzenia żydowskiego, Poznań 2003, page 152-154

Barbara von der Lühe: „Lieber Freund …“ Zur Kontroverse zwischen Bronislaw Huberman und Wilhelm Furtwängler um das nationalsozialistische Deutschland, in: Exil 1933-1945 = Exil. Forschung, Erkenntnisse, Ergebnisse, 24th Edition, No. 1, Frankfurt am Main 2004, page 70-75; Die Kunst im Dritten Reich. Hubermans Verzicht. – Correspondence with Wilhelm Furtwängler (= Copy of the article from the Prager Tagblatt dated 13 September 1933), page 76-78

Hans-Wolfgang Platzer: Bronislaw Huberman und das Vaterland Europa. Ein Violinvirtuose als Vordenker der europäischen Einigungsbewegung in den 1920er und 1930er Jahren = Cinteus. An Interdisciplinary Series of the Centre for Intercultural and European Studies. Fulda University of Applied Sciences, Vol. 17, Stuttgart 2019

Piotr Szalsza: Bronisław Huberman. Leben und Leidenschaften eines vergessenen Genies, aus dem Polnischen von Joanna Ziemska und Team, Vienna 2020

Media:

Orchestra of Exiles, 2012, a film by Josh Aronson, Aronson Film Associates, DVD, 85 min.

Online:

Piotr Szalsza/Monika Kornberger: Huberman, Bronisław, in: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon online, https://www.musiklexikon.ac.at/ml/musik_H/Huberman_Bronislaw.xml

Barbara von der Lühe: Bronislaw Huberman, in: Lexikon verfolgter Musiker und Musikerinnen der NS-Zeit, published by Claudia Maurer Zenck, Peter Petersen, Sophie Fetthauer, Hamburg University, 2017 https://www.lexm.uni-hamburg.de/object/lexm_lexmperson_00002015

Natalia Aleksiun: Huberman, Bronisław, in: The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Huberman_Bronis%C5%82aw

Bronislaw Huberman family page including contemporary photos, record covers, concert programmes and autographs, http://bronislawhuberman.com/

All links listed here and in the comments were last retrieved in September 2020.