The death of a Polish Wehrmacht soldier in Russia: Bernhard Switon (1923-1942)

In 2019, Porta Polonica received an enquiry from a member of the Switon family from Poland who was looking into their family tree. She had an historical photograph of Bernhard Switon from 1942 – a young man of Polish heritage from Recklinghausen in Wehrmacht uniform, just a few months before his death. Bernhard’s mother had sent the photo to his relatives in Poland at the time. 77 years after his death, the relative was now trying to find out more about Bernhard and his family because at some stage contact had been lost with the Switons across the borders. So our research started from this one photo.

For countless families in various countries, the experiences of the Second World War have become a traumatic legacy. But just what exactly do we know about the individual fates of the so-called “Ruhr Poles” in the Second World War? How did Poles end up in military service in the German Wehrmacht on the Eastern front? And how is this part of history anchored in the collective memory of the countries involved?

General historical context

After the three gradual partitions of Poland by the neighbouring powers of Prussia, Austria and Russia, from 1795 to the end of the First World War, Poland as a sovereign state completely disappeared from the map of Europe. The partitioning powers handled the remaining Polish population differently in each of the formerly Polish territories. The political strategy in Prussia was to Germanise the Polish population. Poles who lived in Prussia had Prussian citizenship and are referred to in German secondary literature as “domestic Poles” and those who lived in the other parts are referred to a “Poles living abroad”.[1] The domestic Poles had to learn German in school and were not allowed to live their Polish culture or maintain contact with Poles from other territories. Because of this forced assimilation, Polish migrants involved in the later labour migration were already proficient in German but, despite everything, Polish remained at the forefront of their private and family lives and, to a large extent, helped to form the Polish national identity.

At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, the industrial sector in the German empire began to develop quickly. The rapidly increasing need for labour enticed many workers from the more remote regions into the industrial cities in the Ruhr area and into mining, steel production, construction and brick production. To ensure that domestic Poles who were attractive for the growing labour market were also able to migrate to certain western provinces for work, the legislation bowed to the economic interests of industry. This is how the Ruhr area became “Polonised”, which heralded the birth of the so-called Ruhr Poles. At the same time, however, the rights of the Polish migrants were controlled to such an extent that the Polish culture and language were not able to spread.[2] Calculations show that between 1870 and 1920, up to half a million people who were Polish speaking or of Polish heritage migrated from the rural Eastern provinces of Prussia to the industrial areas on the Rhine and the Ruhr.[3] The lack of social structures for immigrants meant that they quickly created their own Polish clubs in large numbers ensuring that traditions were maintained, the language was kept alive and support was provided.[4] However, the number of members fell drastically in the 1920s and 1930s and some clubs even had to close due to lack of members.

After the end of the First World War and in the global economic crisis, many of the Polish migrants left Germany for personal or economic reasons or because they were motivated by nationalist views. Many former prisoners of war, forced labourers and deported persons returned to the re-formed Polish nation state, others were able to be enticed away and migrated to Northern France.[5] A comparatively small fraction of Poles remained in Germany. After the National Socialists assumed power, a “potential Pogrom atmosphere”[6] eventually developed towards the national minorities, which included the Ruhr Poles. The Prussian citizenship that had been granted to them previously now no longer afforded them political rights comparable to those of the limited circle of German citizens of the Reich.[7]

There were arrests, redundancies, orders for the disbanding of clubs as subversive institutions and seizures of club assets, members of various minorities were disadvantaged in institutions and press censorship steadily intensified. The zenith of this development was the disbanding of all Polish organisations seven days after the outbreak of war in 1939 and the arrest and internment of the leading officials and chairpersons in concentration camps.[8] The large majority of Ruhr Poles, which remained under the radar, was spared for the most part because the mining industry needed a workforce. However, they too were unable to avoid the everyday racism that prevailed in various areas of society. From 1939, the National Socialist policy found another problem with the Polish miners – the possible connections of the Ruhr Poles to the Polish forced labourers since “between 3 and 4 million [Polish-speaking people]” had been trafficked to the German Empire “during the Fascist occupation of Poland”[9]. The concern meant that the activities of the Ruhr Poles were watched very carefully and underwent further restrictions. The children of Polish immigrants were no longer able to attend their Polish lessons but had to subscribe to the National Socialist organisations instead whose aim was to provide the “correct” education for young people.

Ultimately, young Polish men were also drafted into military service because they were unable to escape conscription. It is not clear what the conditions for Ruhr Poles and other minorities were like in the ranks of the Wehrmacht. In 2003, Christoph Rass noted that “[...] with respect to the social structures within the Wehrmacht, the soldiers remain a blank spot in the research landscape”[10]. A similar and even more direct assessment can be found in Ryszard Kaczmarek who notes the following: “The state of research into the soldiers of the Wehrmacht, and its Polish soldiers in particular, can hardly be called satisfactory. The latter hardly feature in contemporary German historical research even though there have long been investigations into members of the Wehrmacht from other countries [...].”[11]

Kaczmarek’s book “Polen in der Wehrmacht” [Poles in the Wehrmacht] deals with the forced “Germanisation” and intake of Poles into the Wehrmacht from the areas that were annexed in 1939. It describes the status of Poles as “second-class citizens and soldiers”[12], but the situation of Poles from the Ruhr area is not dealt with specifically.

[1] Boldt, Thea D.: Die stille Integration. Identitätskonstruktionen von polnischen Migranten in Deutschland. Biographie- und Lebensweltforschung, Volume 11, Frankfurt am Main: 2012, p. 24.

[2] ibid., p. 25 f.

[3] Skrabania, David: The Ruhr Poles, in: https://www.porta-polonica.de/en/atlas-of-remembrance-places/ruhr-poles.

[4] ibid.

[5] Trevisiol, Oliver: Die Einbürgerungspraxis im Deutschen Reich 1871-1945. Diss., University of Konstanz 2004, p. 29.

[6] Kleßmann, Christoph: Zur rechtlichen und sozialen Lage der Polen im Ruhrgebiet im Dritten Reich, in: Archive for Social History, XVII. Volume 1977, p. 179.

[7] Trevisiol, Oliver, p. 75.

[8] Kleßmann, Christoph, p. 187 ff.

[9] Dzikowska, Elżbieta Katarzyna: Polnische Migranten in Deutschland, deutsche Minderheit in Polen – zwischen den Sprachen und Kulturen, in: Germanica, 38, 2006, https://doi.org/10.4000/germanica.422.

[10] Rass, Christoph, „Menschenmaterial“ – Deutsche Soldaten an der Ostfront Innenansichten einer Infanteriedivision; 1939 - 1945 Paderborn; Munich [inter alia] 2003, p. 16 f.

[11] Kaczmarek, Ryszard: Polen in der Wehrmacht. Writings from the Federal Institute for Culture and History of the Germans in Eastern Europe, Volume 65, Munich 2017, p. 13.

[12] ibid, p. 59 f.

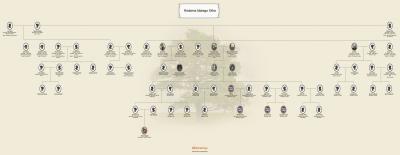

The Switon family

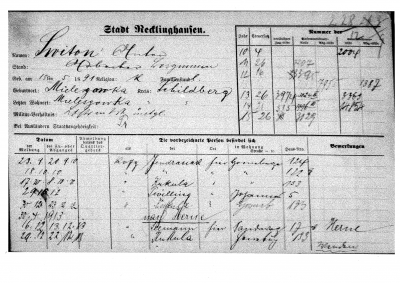

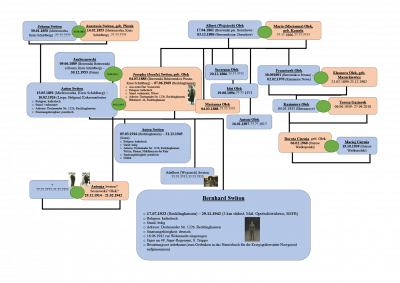

Our research was able to build up part of the family’s story thanks to accounts from one of Bernhard Switon’s uncles, Franciszek, who had known his nephew. However, some of the ambiguities still remain, such as the specific number of children, many of the spouses’ names, and the precise dates, because various factors can often cause oral traditions to be somewhat hazy in the memory of the teller or the listener, and the stories were told several decades ago. We were, however, able to piece together the following information to supplement the documents from the Recklinghausen municipal archives:

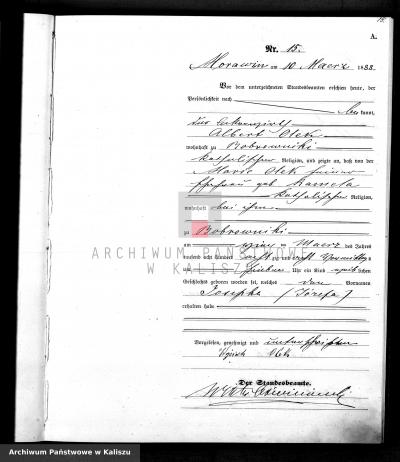

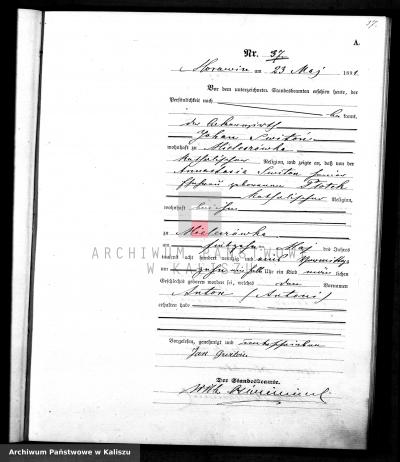

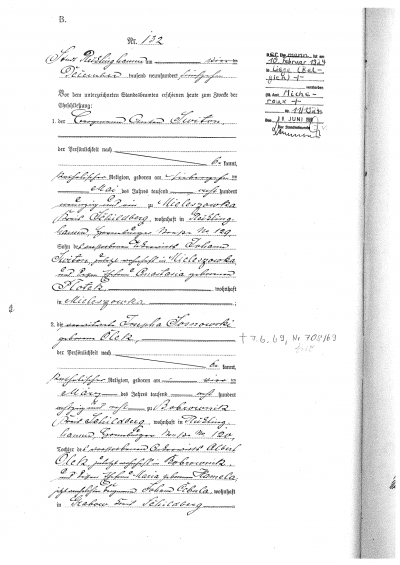

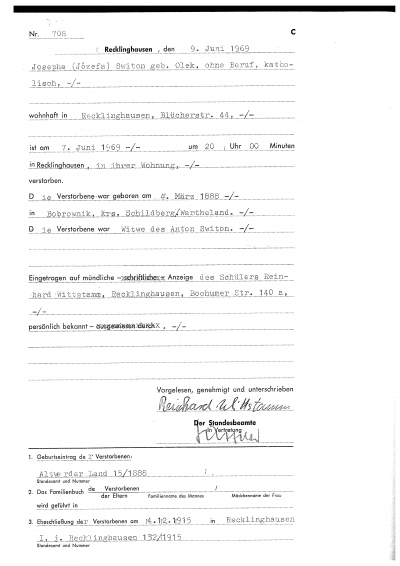

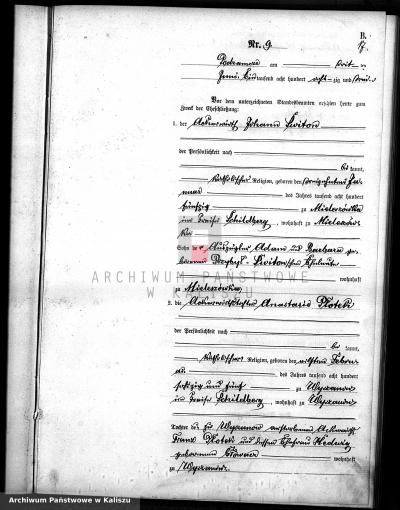

In 1910, Jozefa Olek came to the Ruhr area with her four brothers Antoni, Franciszek, Idzi and Stanisław. Two years later, she married Andrzej Sosnowski, who, like her, had come from the small town of Bobrowniki nad Prosną located between Wrocław and Łódź. It is not clear when and why they separated, but Andrzej left his wife and returned to Poland. The registration indexes and registration documents in the Recklinghausen municipal archives show that Jozefa married again on 4 December 1915 and remained in Recklinghausen with her newly created family. Her second husband was Anton Switon – a worker in the coke plant in Recklinghausen, who also hailed from a small village just a few kilometres from Jozefa’s place of birth. Because the witnesses to the marriage given on the marriage certificate also have Polish names, it can be assumed that the couple moved in their own cultural circles. On the occasion of their marriage, a daughter of Jozefa called Antonja (born 29 December 1914) was recorded, who, according to the uncle’s oral traditions, was Jozefa’s daughter from her first marriage. But apart from a photo that was taken later showing Antonja with her husband, there are no other indications of her whereabouts.

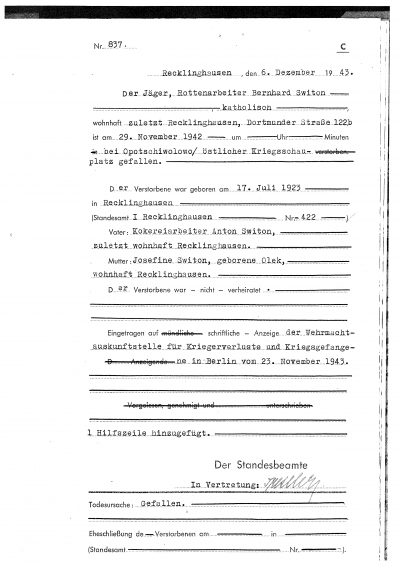

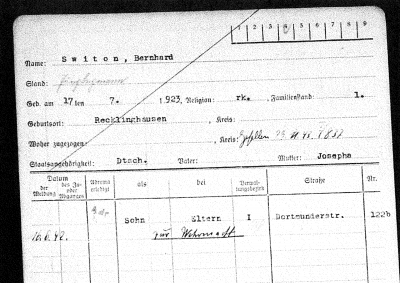

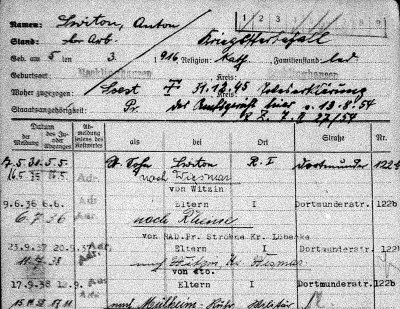

According to the registry documents, Jozefa and Anton’s first son called Anton was born on 5 March 1916 and eight years later, on 17 July 1924, Bernhard Switon came into the world. According to the oral traditions of his uncle’s recollections, there was supposedly another son called Wojciech of whom, however, there is no trace, apart from a photo with the inscription “Adalbert [Pol. Wojciech] in our garden” on the back. It would, however, be conceivable that the person in question was some other relation to the family but we were not able to verify this during our research in Recklinghausen and in Schwelm [based on a photo studio note]. Bernhard’s father died in Liege, Belgium on 10 February 1924 only a few months after Bernard’s birth, which can been seen in a note on the marriage certificate. Whilst it is not apparent why the father of the family was in Belgium without his wife and children, the difficult economic situation could have meant that he had gone abroad to look for work to provide for his family after being made redundant. Jozefa’s brothers Franciszek, Idzi and Stanisław also migrated to France in the same year, 1924; her youngest brother Antoni had died in 1917. It is unclear what the family’s financial situation was like after the death of the father. However, within the “[...] working class [of the Rhenish-Westphalian industrial region] as in parts of the lower middle class, [there prevailed] permanent economic hardship, particularly the threat of parents losing their jobs. This constant social pressure that particularly marked the first half of the 1920s and the global economic crisis, only eased off slightly for working-class families even during the recovery of 1925 to 1929.”[13]

Jozefa, Bernhard’s mother, remained a widow until the end of her life in Recklinghausen. The death certificate also shows that the majority of the witnesses had Polish names indicating that her social environment was presumably still largely made up of Polish friends and neighbours.

According to the resident’s registration card, the family lived in Dortmunder Straße in Recklinghausen, from where both the eldest son Anton, in 1938 at the age of 22, and Bernhard, in 1942 at the age of 19, were conscripted into the Wehrmacht. In contrast to Bernhard, Anton followed the typical route at the time in preparation for military service, completing an RAD[14] of several months following his medical examination, and was drafted into the armed services before he took part in the war. Anton survived the Second World War but died shortly afterwards.

[13] Rass, Christoph, p. 117 f.

[14] Nationalsozialistischer Reichsarbeitsdienst (RAD) [National Socialist Reich Labour Service] – “compulsory work” for young men (and from 1936 for women as well) between 18 and 25 years of age, who carried out community work for low pay. The service was introduced to combat the economic hardship in the country and as an educating authority for young people.

The case of Bernhard Switon in the culture of remembrance of the Second World War

Given that Bernhard Switon was called up to the Wehrmacht on 16 June 1942, i.e. in the middle of the war, and died only a few months later, he must have been sent to the front after only a short initiation. To that point, he had been living with his mother. There were no notes to be found about his employment status; presumably he was still at school. The circumstances which led him to the Wehrmacht are not known either, and it is not known how he was treated in the ranks of the Wehrmacht.

The war graves of fallen German soldiers are usually documented and can be researched via the German War Graves Commission. The German War Graves Commission, funded by donations from relatives and government support, has been working since the end of the First World War to maintain the graves of German soldiers from past wars. The organisation holds international youth workcamps and exhumation initiatives in an exchange with partner organisations from other countries under the guiding principles of “understanding-reconciliation-peace”[15]. The organisation also helps relatives search for the graves of their fallen relatives and organises trips to the relevant sites. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, a war graves agreement was signed between Germany and Russia which allowed the Commission to record and maintain the graves from the First and Second World Wars. The German military cemeteries in Russia as well as the Soviet cemeteries and war memorials in Germany are financed by Germany. This was yet another reason why the Russian President at the time, Boris Yeltsin, agreed to the bilateral governmental agreement on the tending of war graves since Russia did not have the funds to maintain graves and memorials in Germany after the collapse of the Soviet Union.[16] Since then, several German military cemeteries have been opened in Russia and further cooperation has been agreed.

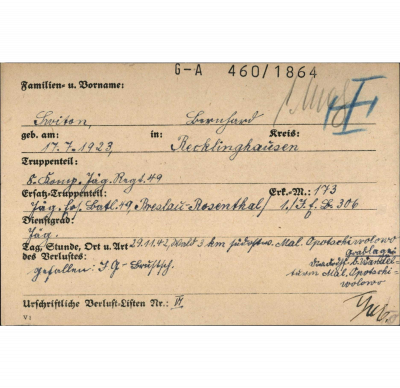

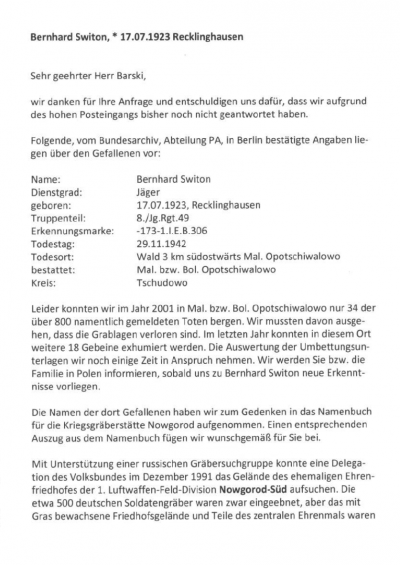

When we made contact with the Commission, the assumption that Bernhard Switon had died on the Eastern Front was confirmed. According to the archives[17], he went to the Russian Soviet Republic as a soldier of the 49th infantry regiment where he fell on 29 November 1942 and was buried in the wood, three kilometres southeast of Moloje Optschiwalowo (a settlement that no longer exists today, approx. 80 km away from Nowgorod Welikij). However, we were not able to be given the current location of his grave as no features identifying Bernhard Switon were found during the exhumation work in the area, which is the only method for identifying the remains of deceased soldiers.

The last time we received information from the War Graves Commission (November 2020), only 62 of 869 fallen soldiers reported by name had been able to be recovered and identified in the area around Nowgorod. Deceased soldiers were identified by the identity disks that every German soldier carried with them. In the case of fallen soldiers, these were broken into two parts – one part remained with the deceased and one part was sent to be documented at the department in Berlin, along with the reference of where the soldier was buried. If the deceased are not found with the corresponding tags, it is often because the burial sites can no longer be clearly located, are not accessible or the identity tags are no longer present because they have been found and stolen by grave robbers who trade in Wehrmacht militaria on the black market.

The deceased who were buried in the area of Nowgorod Welikij were then buried in the German military cemetery (Pankowka) in Nowgorod, which was opened in the grounds of the former cemetery of the 1st Nowgorod South Luftwaffe Field Division in 1996. As Switon’s identity tag has not yet been found, it is not clear whether he has not yet been exhumed or whether he remained nameless when the bodies were moved to Nowgorod cemetery. On the other hand, however, Switon, like hundreds of other fallen soldiers reported by name, was recorded in the German War Graves Commission’s commemorative book for the Nowgorod war graves.

[15] Siegl, Elfie: Versöhnung über Gräbern: Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge in Russland, in: Zeitschrift Osteuropa, Vol. 58, No. 6, Geschichtspolitik und Gegenerinnerung: Krieg, Gewalt und Trauma im Osten Europas, June 2008, p. 309.

[16] cf.: ibid., p. 309 f.

[17] Information about fallen soldiers from the Federal archive, PA department in Berlin, which was made available to the German War Graves Commission.

To this day, the attitude toward German military cemeteries in Russia is very divided. On the one hand, people are happy that the remains of German soldiers found near[18] them are being reburied, which also appears to be the best solution according to the Christian tradition of a “reasonable burial”. On the other hand, many people in Russia seem to find it disconcerting that the warmongers who attacked the country should be buried “honourably” in a cemetery in their country. This has to do with the fact that the commemoration of soldiers in Russia is equated with honouring the deceased as victors. For many decades, this attitude was characterised by the systematic idealisation of the victory in the Patriotic War[19] and of the honouring of soldiers as heroes. The “Soviet Russian culture of interpretation of the Great Patriotic War was, from the very start, arrogant and multifaceted, and yet it too was based on a central distinction: the distinction between the victors and the vanquished”[20] and so did not leave a lot of scope for classification into different groups of victims and perpetrators. Since the 1960s, the “heroical commemoration of the war”[21] has taken on greater significance among the general public in the Soviet Union and Russia. Right up to the present day, the remembrance of this war is seen as one of the most important events in Russian culture and is celebrated on several days of the year. “The public holidays which commemorate victory in the Second World War are still extremely important in Russia [...] 71.5 percent consider these days to be important which is why they are considered even more meaningful than Christmas, for example [...]”[22]. The significance of these celebrations is so great that the celebratory parade to mark the 75th day of the victory in the Patriotic War was not even cancelled during the coronavirus crisis of 2020, but was instead just moved from 9 May 2020 to 24 June 2020[23].

From this perspective, negotiations relating to the German memorial sites in Russia are proving rather difficult, which is evident from Russian newspaper articles online. In the articles about the cemeteries, the headings range from “Graves found in cellars” (Dnovec magazine, 2018) and “The 95-year-old former Wehrmacht soldier Hugo Bosse came to the Nowgorod region“ (53 Novosti, 2018), which show objective or positive representations of the war graves work, right up to “Russia’s body is covered with the abscesses of fascist memorials” (RVS, 2015) and “German War Graves Commission is preparing a pompous reburial ceremony under Volgograd” (SM News, 2019). The Commission rejects those accusations of a victory ceremony for German soldiers:

“Military cemeteries are not places where the dead are honoured but where they find their last resting place.”[24]

To avoid there being any perception at all that German soldiers are being honoured, the War Graves Commission is installing commemorative plaques with collective names and a few inscribed crosses in the cemeteries instead of individual gravestones. It is also notable that commemorative plaques have also been erected for Spanish and Flemish soldiers in the German military cemetery in Nowgorod, but Polish soldiers are not mentioned. This has to do with the fact that the Poles from the East who were conscripted into the Wehrmacht were mainly sent to the Western Front and those of Polish origin in the West were listed as German nationals in the military archives. It is also possible, however, that many of the Ruhr Poles were sent to the Eastern Front as many Polish surnames can be found in the extract from the War Graves Commission’s list of names relating to the Nowgorod cemetery. The documents do not reveal what fate befell the individual Wehrmacht soldiers in the territory of the Soviet Union. It is easy to imagine that there were many deserters, particularly among those soldiers who were forced to join the Wehrmacht. It cannot be ruled out that this was also Bernhard Switon’s position but our research did not reveal insights into his attitude towards the Nazi regime or about his activities on the Eastern Front or the exact cause of his death.

The subject of the participation of various players in the Second World War is also viewed critically in Poland in the context of the issue of guilt. This is why information about Donald Tusk’s grandfather being in the Wehrmacht[25] made headlines and why there was lot of fuss around Kaczmarek’s work “Polen in der Wehrmacht” [Poles in the Wehrmacht] because, according to Kaczmarek:

“[…] [there was ] little awareness for the fact that an ethnic German could also be a Pole in the ethno-cultural sense, who had been assimilated into the German “people’s community” under duress [...]. It was a shock to realise that ethnic Poles [...] served in the Wehrmacht in their droves not just in individual cases, particularly since there had been little doubt in Poland that the Wehrmacht was jointly responsible for war crimes.”[26]

[18] Even today, the remains of very many fallen soldiers still lie where they were temporarily buried during the war and on top of which houses, streets or parks have been built as time passed.

[19] The Great Patriotic War is the name given in Russia to the Soviet Union’s fight against Hitler’s Germany 1941-1945.

[20] Langenohl, Andreas. „Staatsbesuche: Internationalisierte Erinnerung an Den Zweiten Weltkrieg in Rußland Und Deutschland." Osteuropa 55, No. 4/6 (2005): p. 85. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44932726.

[21] Jahn, Peter: 22 June 1941: Kriegserinnerung in Deutschland und Russland (30.11.2011), in: http://www.bpb.de/apuz/59643/22-juni-1941-kriegserinnerung-in-deutschland-und-russland?p=all.

[22] Rüschendorf, Raphael Felix: Stalingrad im kollektiven Gedächtnis der Wolgograder Bevölkerung. Wie sich der Generationenwechsel auf die Erinnerung auswirkt (02.02.2017), https://erinnerung.hypotheses.org/1067.

[23] Moreover, the first parade after the Second World War was held in Moscow on 24 June 1945.

[24] Siegl, Elfie, p. 310.

[25] Only after the election campaign for the presidency in 2005 did it emerge that Donald Tusk’s grandfather had been in forced labour and concentration camps between 1939-42, before being conscripted into the Wehrmacht in 1943 after his release, and later managing to switch to the Polish Armed Forces (PSZ). Cf.: Kaczmarek, Ryszard, p. 16 f.

[26] Kaczmarek, Ryszard, p. 18.

Conclusion

For Bernhard Switon, as for many other conscripted soldiers, participation in the Second World War was a fate that people were not able to avoid at the time. It must have been a conflicting situation for many young people from the Ruhr area, who belonged ethno-culturally to Poland although they were German nationals, because in all likelihood they were brought up in both the spirit of the ideology of the Third Reich, and with Polish cultural values, traditions and language within their families, and were suddenly conscripted into a war in which they also had to march through occupied Poland. The conscription to military service was compulsory for those with German citizenship and enforced naturalisation for this purpose was not uncommon. But at the same time, the presence of people of Polish origin in the ranks of the Wehrmacht was at odds with the race ideology of National Socialism. This led to discrimination, but there is no evidence of any discrimination towards Ruhr Poles.

Bernhard Switon was one of these people and, as a very young man – almost a child still – was sent without any extensive training to the Eastern Front in 1942 where he fell a short time later. Ultimately, it is not clear whether he was drawn into the war voluntarily because he was brought up within the relevant ideology, or whether he was forced into it, as was so often the case with Polish citizens in Poland after 1939. One thing is certain, however, that his story is probably not unique, but is likely representative of many young men of Polish origin from the Ruhr area who were in the Wehrmacht and on the Eastern Front, whose life stories have not yet been thoroughly addressed. Overall, research into the history of people of Polish origin from the Ruhr area who were in the Wehrmacht still seems to be very limited – and the culture of remembrance in the neighbouring countries brings with it the potential for conflict when it comes to this subject matter. One thing is clear: The name of Bernhard Switon remains linked to a place he never belonged.

Kathrin Lind, December 2020

A special thanks goes to the photographer Dmitry Grigoryev for the images of the German military cemetery in Nowgorod Welikij that he provided.

Особую благодарность выражаем фотографам Дмитрию Григорьеву и Олегу Тиняеву за предоставленные фотографии Немецкого военного кладбища (Новгород Великий).

Bibliography

Boldt, Thea D.: Die stille Integration. Identitätskonstruktionen von polnischen Migranten in Deutschland. Biographie- und Lebensweltforschung, Volume 11, Frankfurt am Main 2012.

Dzikowska, Elżbieta Katarzyna: Polnische Migranten in Deutschland, deutsche Minderheit in Polen – zwischen den Sprachen und Kulturen, in: Germanica, 38, 2006, p. 11-24, https://doi.org/10.4000/germanica.422.

Jahn, Peter: 22 Juni 1941: Kriegserinnerung in Deutschland und Russland (30.11.2011), in: http://www.bpb.de/apuz/59643/22-juni-1941-kriegserinnerung-in-deutschland-und-russland?p=all.

Kaczmarek, Ryszard: Polen in der Wehrmacht. Schriften des Bundesinstituts für Kultur und Geschichte der Deutschen im östlichen Europa, Volume 65, Munich 2017.

Kleßmann, Christoph: Zur rechtlichen und sozialen Lage der Polen im Ruhrgebiet im Dritten Reich, in: Archiv für Sozialgeschichte, XVII. Volume 1977, p. 175-194.

Langenohl, Andreas: “Staatsbesuche: Internationalisierte Erinnerung an Den Zweiten Weltkrieg in Rußland Und Deutschland.” Osteuropa 55, No. 4/6 (2005), p. 74-86. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44932726.

Rass, Christoph: “Menschenmaterial” – Deutsche Soldaten an der Ostfront Innenansichten einer Infanteriedivision; 1939-1945 Paderborn; München [inter alia] 2003.

Rüschendorf, Raphael Felix: Stalingrad im kollektiven Gedächtnis der Wolgograder Bevölkerung. Wie sich der Generationenwechsel auf die Erinnerung auswirkt (02.02.2017), https://erinnerung.hypotheses.org/1067.

Siegl, Elfie: Versöhnung über Gräbern: Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge in Russland, in: Zeitschrift Osteuropa, Vol. 58, No. 6, Geschichtspolitik und Gegenerinnerung: Krieg, Gewalt und Trauma im Osten Europas, June 2008, p. 307-316.

Skrabania, David: Die Ruhrpolen, in: https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/atlas-der-erinnerungsorte/die-ruhrpolen, last accessed on 14/12/2020.

Trevisiol, Oliver: Die Einbürgerungspraxis im Deutschen Reich 1871-1945. Diss. 2004. Das institutionelle Repositorium der Universität Konstanz, Suche im Bestand ‚Geschichte und Soziologie‘, WEB: http://d-nb.info/974206237/34.