From the “pit” to the professional league: Poles and Masurians in Ruhr area football

The “Ruhr Poles“

Before the First World War labour migration from the Polish-speaking provinces of the German Reich had led to the emergence of a Polish-speaking minority, estimated at around 300,000-400,000 people in the Rhine-Westphalian industrial region. In addition, half of them were migrants from East Prussia, especially Masurians, who were often confused with “Poles” and whose migration centre was Gelsenkirchen. The Masurians spoke an old Polish dialect, but in contrast to the “Poles” they were Protestant and traditionally Prussian. Hence they deliberately dissociated themselves from other Polish-speaking migrants in the Ruhr area. Nonetheless, the contemporary majority population confused Masurians with “Polish” immigrants and they suffered from the same experiences of discrimination. Academics too, have often found it impossible to distinguish between the different ethnic groups and identify them clearly.

The Ruhr Poles, who were predominantly employed in the Rhineland-Westphalian mining industry, soon organised their own civil societies in a widely differentiated system of associations in order to cultivate their native culture and language : women's associations, youth associations and gymnastics clubs (the so-called Sokołvereine), where male immigrants in particular came together in the spirit of Polish nationalism.

Weimar Republic: the rise of soccer

After the First World War, the Polish minority in the Ruhr area shrank to an estimated 150,000 people, less than 40% of its original size. This was due to emigration back to the re-established Polish state and further emigration to France, Belgium and the Netherlands. Before 1914 there had been separatist, national Polish tendencies in the minority population, including a flourishing club system, but for those who remained assimilation was now a rational choice for the future – and a career in football was an attractive option as a way out of the “pit” or any other physically heavy and unhealthy job.

Previous to this – in contrast to a long-established social-romantic legend – football in its infancy in Germany was not a workers' sport, but an area dominated by white-collar employees and bourgeois professions. This situation was to change in the Ruhr region after the First World War. Now the multi-ethnic and proletarian dimensions of football were gaining in importance among the region's immigration community. Especially in the immediate vicinity of the large collieries, teams with predominantly proletarian members and proletarian supporters emerged. Due to its proximity to the Consolidation colliery, with which the club was closely connected in terms of personnel and material, the football club Westfalia Schalke (later FC Schalke 04) became the prototype of a Ruhr district club that reflected the social reality of the immigrant community. Other “classical” clubs in the Ruhr area, like the Spielvereinigung Herten or Hamborn 07, now experienced their rise as clubs from the colliery estates. Polish and Masurian names – they can no longer be separated credibly at this time – were now commonplace amongst the region's clubs.

In the 1937/38 Gauliga season, 15 clubs from the Ruhr region played for the Gaumeisterschaft, with each club using at least one player with Polish roots: Rodzinski, Pawlowski, Sobczak, Lukasiewicz, Tomaszik, Piontek ... During the entire season, 68 players of this category are mentioned. In addition to the players, people with Polish names in a wide variety of functions were also frequently found in the clubs in the region. For example, the traditional club Rot-Weiss Essen, which counted numerous members with Polish names since 1919; these also included functionaries and employees. Until 1939, people with Polish name roots accounted for approximately 10% of Rot-Weiß Essen's membership. At the same time, however, name changes sometimes also became noticeable. This was a clear sign of the assimilation tendencies of the Ruhr Poles and their descendants who remained in the Rhineland-Westphalian Ruhr region: From 1931, one of Rot-Weiß Essen's employees was the groundsman Hermann Greszick, who changed his name to Kress in 1932. Other players changed their names from Regelski to Reckmann, from Czerwinski to Rothardt and from Zembrzyki to Zeidler ... Members with Polish names were also found in socialist workers' sport in the Ruhr area, e.g. in the board club of Arbeiter-Turn- und Sportverein Schonnebeck in Essen-Schonnebeck. Higher-class football in the district in particular was now strongly influenced by players with a Polish migration biography. Even the German national soccer team had players like Szepan, Kuzorra, Gellesch, Urban, Kobierski, Zielinski and Rodzinski among its ranks.

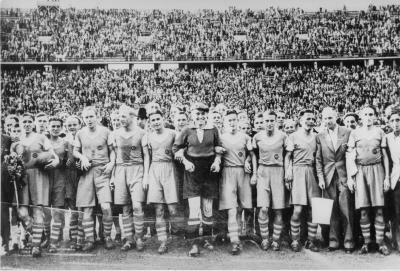

Schalke as a model case: a mirror of migration history in the Ruhr area

A glance at FC Schalke 04, the Gelsenkirchen prototype of the “Polack and Prole club”, to which the first four of the aforementioned national players belonged, reveals the complexity and confusion that the immigrant society in the area had developed into over the years. Between 1934 and 1942 Schalke won the German Championship six times. The team was peppered with players with Polish-sounding names, most famously the national players Ernst Kuzorra and Fritz Szepan. When Schalke won the Championship for the first time in 1934 and posed in front of the camera with arms raised high in the Hitler greeting, the Polish press mocked them as “Polish German football champions”. Upon which the club management hastened to prove the opposite by pointing out that the players were not “emigrants” and that even their parents had been born in Germany. The majority of the parents of the Schalke players came from southern East Prussia. They did not belong to the Polish immigrants per se, but to the Protestant circle of Masurians loyal to Prussia. Between 1920 and 1940, 30 players in the Schalke team were identified as Masurians, three of whom had been born in Masuria. The Gelsenkirchen Championship team thus reflected the migration history of the region and the social background of the Masurian migration centre, Gelsenkirchen. In this way, players with Polish or Masurian family origins guaranteed the strength of Ruhr area football (especially of Schalke) during the “Third Reich”, but also of the German national team. National Socialist “Volkstumsforschung” employees, who conducted anti-Polish, racist and biological research, solved this dilemma by only finding Masurians in the territory and declaring them to be “German” in their culture and mentality. Here they already saw signs of “Umvolkung” or Germanisation of “inferior” foreign immigrants. The Masurian Schalke stars Kuzorra and Szepan then allowed themselves to be harnessed to the regime's propaganda campaigns and joined the NSDAP. Szepan profited from this “Aryanisation” and took over the Jewish department store Julius Rhode on the Schalke market place.

The post-war period: the third generation

After the Second World War, the collapse of civilisation between 1933 and 1945 resulted in a lengthy suppression of memories of the ethnically heterogeneous social history of the region. In football, however, the children and grandchildren of “Polish” and Masurian migrants were still present. Between 1945 and 1950 the players in the team at Sportfreunde Katernberg in Essen were Jerosch, Kosinski, Pisarski, Majewski, Mieloszyk, Radziejewski and Rynkowski. When SV Sodingen qualified for the final round of the German Championship in 1955, half of the team had Polish or Masurian-sounding names: Sawitzki, Kropla, Lika, Nowak, Adamik, Dembski and Konopczinski. The history of the third generation of immigration was still visible in football. Hans Tilkowski, grandfather of the aforementioned Borussia Dortmund star, had immigrated from West Prussia to the mining area. The goalkeeper's father was still a miner and he grew up in the housing settlement attached to the Zeche Kurl (colliery). Reinhard “Stan” Libuda (1943-1996), the star of the Ruhr area football team, who played for Schalke, Borussia Dortmund and the national football team and who tragically died at an early age, was very much aware of the similarity between his career and his origins and the life of the great French national player Raymond Kopa(szewski) from the Polish miners' milieu in France. But the general public remained ignorant of this fact.

Transnational influence: Northern France

In the Polish milieu in the coal mines of northern France, the history of the Ruhr and the involvement of Polish immigrants in football was actually perpetuated or found its equivalent. In 1948, when RC Lens faced OSC Lille in the final of the French Cup, Lens lost 2-3, but fought back twice from behind against their opponents with goals by “Stanis” Stefan Dembicki. That said, the highly popular Polish-sounding striker was neither born in Poland nor France. But in 1913 in the German coal-mining district in Dortmund-Marten. He was descended from the first generation of Polish-speaking migrants in the German Ruhr region. After the First World War, Dembicki moved to France with his family, signed on in a colliery at the age of 13 and worked in one of the collieries in Lens until his retirement in 1968. In his old age he ran a tobacco bar, which also served as an advance booking office for match tickets and a meeting point for the “Racing” fan club. It was called “Sang-et-or” (Blood and Gold) after the club colours. Here there are obvious reverberations with the tobacco shop owned by the Schalke star Ernst Kuzorra, which was then passed on to “Stan” Libuda.

Women footballers with a Masurian or Polish migration background

As early as the 1950s, after the Second World War women's football teams also developed in the Ruhr area – despite the ban imposed by the German Football Association (DFB). These formed the basis for an unofficial national team. Two important personalities among the early pioneers of women's admission into football and the fight against their discrimination by the DFB, which lasted until 1970, were Brunhilde Zawatzky of Fortuna Dortmund and Lore Karlowski of Kickers Essen. Both women came from families with an immigrant background. Lore Karlowski's father came from a Masurian family and worked as a miner at the Nordstern colliery. At the age of sixteen, Lore made football history when she ran out against Holland in front of 18,000 spectators at the first international match played by an unofficial German women's national football team on 23rd September 1956 in the Mathias Stinnes Stadium in Essen. The German team won 2-1.

The professional era: Emigrants and “Legionnaires”

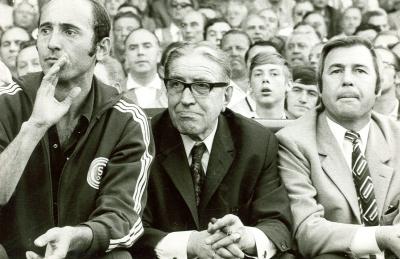

After the introduction of the Bundesliga and professionalism in German football in the 1963/64 season, the German market also became attractive for Polish players. The first Pole to play for a German club in the region was Waldemar Piotr Słomiany, who played for Schalke between 1967-1970 and moved to the “Pit” from the Upper Silesian mining area of Górnik Zabrze and a club that proudly bears its mining heritage in its name. Since the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989/90 German and Polish football has become even closer. And since the 2012 European Championships in Poland and the Ukraine at the latest, this proximity has moved into the public eye. The Polish trio Łukasz Piszczek, Jakub Błaszczykowski and Robert Lewandowski played an outstanding role in the Borussia Dortmund team that were German Champions in 2011 and 2012. In Poland the club was given the benevolent tab, “Polonia Dortmund”, a name that follows on from the great era of the Ruhr region club Schalke 04 with its many players with Polish and Masurian names from the Polish coal-mining community. In spring 2014, a total of 23 Polish players were under contract in the three professional leagues of German football. German players from the milieu of Polish immigrants, like Miroslav Klose and Lukas Podolski, both of whom were born in Poland, were also among the top performers in the German national team which won the World Cup in Brazil in 2014.

And the game goes on. Not only in view of the current two million Germans with Polish family backgrounds, the hope remains that football will build another bridge between the neighbouring countries of Germany and Poland.

Diethelm Blecking, august 2019

Further reading:

Blecking, Diethelm, Von Willimowski zu Lewandowski: Die Rolle polnischer Spieler im deutschen Elitefußball, in: Dossier, Bundesliga Spielfeld der Gesellschaft, Bundesanstalt für politische Bildung 2014 (http://www.bpb.de/gesellschaft/medien-und-sport/bundesliga/192009/polnische-spieler-im-deutschen-elitefussball).

Blecking, Diethelm, Die Nummer 10 mit Migrationshintergrund, Fußball und Zuwanderung im Ruhrgebiet, in: Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, 1-3/2019, pp. 24-29 (http://www.bpb.de/apuz/283266/fussball-und-zuwanderung-im-ruhrgebiet).

Huhn, Daniel/ Metzger, Stefan, Eingewandert, ausgewandert und weitergespielt, in: Dietmar Osses (ed.), Von Kuzorra bis Özil. Die Geschichte von Fussball und Migration im Ruhrgebiet, Essen 2015, pp. 49-57.

Lenz, Britta, Vereint im Verein? Städtische Freizeitkultur und die Integration von polnischen und masurischen Zuwanderern im Ruhrgebiet zwischen 1900 und 1939, in: Archiv für Sozialgeschichte 2006, pp. 183-203.

Lenz, Britta, „Gebürtige Polen“ und „deutsche Jungen“, Polnischsprachige Zuwanderer im Ruhrgebietsfußball im Spiegel von deutscher und polnischer Presse der Zwischenkriegszeit, in: Diethelm Blecking et al. (ed.), Vom Konflikt zur Konkurrenz: Deutsch-polnisch-ukrainische Fußballgeschichte, Göttingen 2014, pp. 100-113.

Mandic, Vanja, Lore Barnhusen, geborene Karlowski, Nationalspielerin trotz Verbots, in: Dietmar Osses (ed.), Von Kuzorra bis Özil. Die Geschichte von Fußball und Migration im Ruhrgebiet, Essen 2015, pp. 154-155.