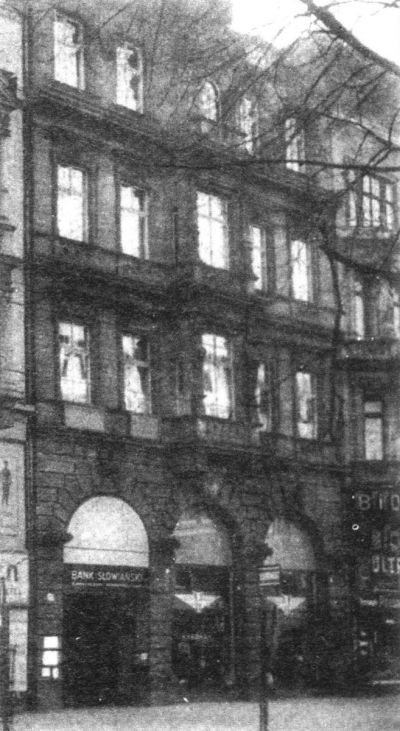

The "Polenmarkt" at Potsdamer Platz in Berlin

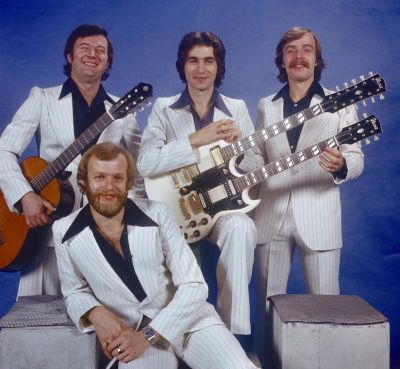

“West Berlin, West Berlin, on every second pavement stands a Pole”, sang the band "Big Cyc"in 1990, and the satirical lyrics were perfectly in line with reality. The song was written after the band had travelled by train to a concert in Germany. On an overcrowded train from Warsaw to Berlin, the musicians soon realized that there was no one among their fellow travellers who wanted to visit West Berlin as a tourist. Their luggage consisted of all kinds of goods - from foodstuffs, such as Polish sausages, meat, eggs, butter and marinated mushrooms, via dishes and clothing, live and stuffed animals, to the mandatory cartons of cigarettes and alcohol. All these products were destined for the Polish market on the Reichpietschufer, very close to Potsdamer Platz, which still lay empty at that time.

In 1989 and 1990 such scenes were constant occurrences on trains leaving Polish cities for Berlin. At its height the market expanded so rapidly that the borders of West Berlin, which was still separated from East Berlin by the Wall, were crossed daily by up to 300 buses, dozens of trains and an unpredictable number of tiny Fiats.[1]

The mass stampede to West Berlin was helped by the abolition of visa requirements for Polish travellers in early 1989. Every citizen of the People's Republic of Poland was now allowed a passport without the threat of harassment by the Communist security apparatus. West Berlin attracted the Poles like a magnet, as this was the only city open to them. Those who wanted to travel to the GDR still needed an invitation, while the authorities in the Federal Republic required an invitation, the possession of 50 DM per day and proof of health insurance. However, these rules did not apply to West Berlin. Citizens from the Eastern Bloc were allowed to stay there for 31 days in accordance with Allied regulations. A large number of Poles decided to exploit this privilege, and Berlin citizens who witnessed such scenes near the Berlin Wall saw people "(...) loaded down with nylon bags, dragging behind them overloaded two-wheeled carts. They travelled in endless lines from the border crossing at the Friedrichsstraße railway station in East Berlin to the square in front of the opera house and the park at the Landwehrkanal, until they reached the thousands of people, and "shops" on the barren spot between the Turkish flea market and the railway line used for testing the magnetic train.”[2]

The trade of the Poles "with anything whatever", in humiliating circumstances, on dusty soil and in mud, in heat and bad weather, but above all in constant fear of confiscation of goods cleared neither by Customs officials nor by the police, was not so much due to their natural tendency to do business, but rather forced by the extremely precarious economic situation of many Polish families. A sale of 20 short-sleeved blouses, which cost 2 DM in Poland, could bring in a monthly income of about 40 DM in Berlin. In this respect, the Polish market was primarily a phenomenon of its time.

Initially, Berliners were naturally interested in the massive influx of Polish traders into their city. The provisional market became the destination of weekend excursions, visited by both native Germans and migrants who purchased the most peculiar articles. Most people did not worry about the existence of the Polish market until it became so large that it was difficult to control.