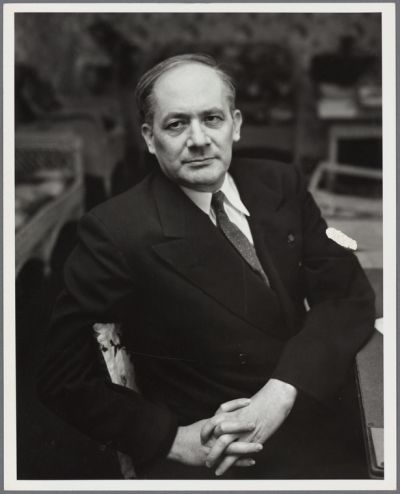

Raphael Lemkin – the man who coined the term “genocide”

Raphael Lemkin was born Rafał Lemkin on 24 June 1900 to a Polish-Jewish family of modest means in Bezvodne, a village in the Volkovysk region, not far from Grodno in what is now Belarus. His father, Józef Lemkin, leased a farm, which was unusual at that time for someone of his faith. In his autobiography, “Totally Unofficial”, Lemkin described the area in which he was born as follows: “I was born in a part of the world historically known as Lithuania or White Russia, where Poles, Russians (or, rather, White Russians), and Jews had lived together for many centuries. They disliked each other and even fought, but in spite of this turmoil they shared a deep love for their towns, hills and rivers. It was a feeling of common destiny that prevented them from destroying each other completely”.[1]

Even as a child, Raphael Lemkin was fascinated by history. One of the first books that influenced the decisions that he would make later in life was “Quo Vadis” by Henryk Sienkiewicz. Lemkin was so impressed by the novel that he started to search for similar examples of persecution in the history of mankind. “I was fascinated by the frequency of such cases, by the great suffering inflicted on the victims and the hopelessness of their fate, and by the impossibility of repairing the damage to life and culture”, he wrote in his memoir.[2] As a teenager, he experienced the barbarity of war first hand when Volkovysk town and the surrounding region were occupied by the Germans in 1915. However, he managed to escape to Białystok, where he attended the grammar school, completing his school education in 1919. Shortly afterwards, the Polish-Soviet war broke out, and the fresh-faced school graduate joined a medical corps of the Polish Army near Volkovysk. After the war, he first went to Kraków, where he studied law at Jagellonian University. In 1921, he moved to Lwów (now Lviv), where he enrolled at the Faculty of Law at Jan Kazimierz University. During this time, he attended seminars held by highly-regarded professors of law, such as Juliusz Makarewicz and Leon Piniński. In 1922, Lemkin also translated the Soviet Penal Code into Polish. His many travels, some for research purposes, took him to Berlin University and the Sorbonne. In 1926, he enrolled at the Faculty of Philosophy in Heidelberg.

The start of his life’s work

The events of the 1920s further fuelled Lemkin’s interest in issues relating to criminal responsibility for the destruction of population groups and entire peoples. He was particularly impacted by the shooting of Talaat Pasha on the street in broad daylight in Berlin in 1921. The former Turkish minister of the interior [during the First World War] was the person who bore the main responsibility for the genocide of the Armenians. The gunman was a young Armenian who had lost 89 members of his family during the massacres of 1915–1917 (the word “genocide” did not yet exist during that time - author’s note). Talaat Pasha was living under a false name in Berlin, and it was not possible to try him before a court for his crimes. Instead, he was merely sentenced to death in Armenia in absentia. The fundamental principle of the sovereignty of states meant that it was impossible to find someone guilty of ethnically motivated murder committed in a different country.

“Why is a man punished when he kills another man, yet the killing of a million is a lesser crime than the killing of an individual?”[3] This was the question that Raphael Lemkin put to one of his professors at the university in Lwów, and it set in motion the task to which the ambitious lawyer would dedicate his life: the creation of a legal basis for the unification of moral and legal standards regarding the destruction of national, racial, and religious groups.[4] Lemkin knew that it would not be possible to realise his objective without supporters, and he set out to make the necessary contacts. During this time, he also quickly gained status in his legal career, becoming deputy public prosecutor of Warsaw in 1929. Soon afterwards, he was promoted again, this time to secretary of the penal section of the Polish Committee on Codification of Laws (Komisja Kodyfikacyjna RP), where he worked on the development of the Polish penal code. He was also a representative of the International Bureau for the Unification of Penal Law, where he worked with the most prestigious lawyers in western Europe. Then, in October 1933, at the international conference for the unification of penal law in Madrid, he took steps to push through his concept for the recognition of the annihilation of ethnic, religious or racial groups as a crime. His decision to do so was triggered by the political situation in Europe at the time: “Hitler had already promulgated his blueprint for destruction. Many people thought he was bragging, but I believed that he would carry out his program if permitted. The world was behaving as if it were ready to acquiesce in his plans. The Polish government was negotiating a non-aggression pact with Germany. In the circles of the League of Nations, my friends were making sarcastic remarks about the pact, which they thought would undermine collective security. Now was the time to establish a system of collective security for the life of the peoples.”[5]

[1] Frieze, Donna-Lee (ed.): Raphael Lemkin. Totally Unofficial. The Autobiography of Raphael Lemkin, Yale University Press New Haven & London, 2013, p. 3.

[2] Ibid., p. 1 f.

[3] Brockschmidt, Rolf: Das unfassbare benennen, in: “Tagesspiegel”, 13/2/2022, URL: https://www.tagesspiegel.de/wissen/wie-raphael-lemkin-den-genozid-begriff-praegte-das-unfassbare-benennen/28062128.html (last accessed on 7/4/2022).

[4] Frieze, Donna-Lee (ed.): Raphael Lemkin. Totally Unofficial, p. 19.

[5] Ibid., p. 22.

The crimes of barbarity and vandalism

Even before the conference in Madrid, Raphael Lemkin had already differentiated between two types of crime: barbarity as the annihilation of national or religious groups, and vandalism as the destruction of all cultural goods, which aimed to both eradicate the traditions of the persecuted groups and to destroy their intellectual and spiritual life. He explained the necessity of introducing both terms into the penal code as follows: “Is not the destruction of a religious or racial collectivity more detrimental to mankind than destroying a submarine or robbing a vessel? When a nation is destroyed, it is not the cargo of the vessel that is lost but a substantial part of humanity, with a spiritual heritage in which the whole world partakes. These people are being destroyed for no other reason than that they embrace a specific religion or belong to a specific race. They are destroyed not in their individual capacity but as members of a collectivity of which the oppressor does not approve. The victims are the most innocent human beings of the world.”[6]

However, the concept received a cool reaction, both in Madrid and at home in Poland. The Polish government refused to allow Lemkin to travel to Spain. Although his theories made an impact at the conference, they attracted support from only a limited number of people. The warnings regarding the political situation in the Third Reich and the discrimination of the Jews were not only met with incomprehension, but were even regarded in Poland as being an “insult to our German friends.”[7] Shortly afterwards, Raphael Lemkin was recalled from his post as state prosecutor. However, rather than deterring him, this had the opposite effect: he continued with his attempts to disseminate his ideas, seeking support by participating in numerous conferences in Europe and throughout the world.

Life in exile

Lemkin’s work was interrupted by the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany. During the first few days of September, he left Warsaw and fled eastwards. When the eastern regions were occupied by the Soviets, he managed to reach Vilna (Vilnius), and finally, Kaunas in Lithuania, where, thanks to his contacts made at international conferences, he was able to obtain a visa to travel to Sweden. In 1940, he travelled to Stockholm via Riga. After just a few months, during which time he learned Swedish, he began giving lectures on law at the university in Stockholm. During this period, he observed the continuing de-humanisation of the Jewish population by the National Socialists, as well as the destruction caused by the war, from the perspective of a neutral country. In 1941, Lemkin was offered a post at Duke University in North Carolina. The journey to the US took him first to Moscow, from where he boarded the last train of the Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok [before Germany attacked the Soviet Union - translator’s note]. From there, he travelled by ship to Japan, and thence to the US. In addition to working at the university, he was also a member of the US President’s Board of Economic Warfare. In 1942, Lemkin began an information campaign in the US on the National Socialist crimes in Europe. In this context, he translated the National Socialist decrees into English and analysed them on this basis. He showed that German law had fallen prey to the nefarious and destructive goals of Adolf Hitler. In 1942, he became an advisor on the Board of Economic Warfare in Washington, an authority created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Second World War. Here, Lemkin continued his work on disseminating the truth about the crimes occurring in Europe; at this time, he was still using the terms “barbarity” and “vandalism”. Meanwhile, he became increasingly convinced that the unprecedented nature of the murders being committed in this war made it necessary to create a new word that better described the nature of these crimes.[8]

The definition of genocide

In 1944, Raphael Lemkin published his book “Axis Rule in Occupied Europe”. He gave one chapter the title “Genocide - A New Term and New Conception for Destruction of Nations”. This publication was an extremely thorough documentation of the Nazi crimes, even though at that time, the author was not yet even aware of the full extent of the crimes. Even so, the book was a milestone. For the first time ever, it defined one of the worst crimes against humanity: genocide, or the intended annihilation of population groups or entire nations on the basis of their being different. For Lemkin, the concept of genocide was very broad, and also included measures intended to destroy the identity of those being persecuted. In other words, it also extended to cultural, religious, political, social, and economic aspects. The publication of the book was received positively by the “Washington Post”, the “New York Times” and others, and the word “genocide” began to be used in international legal terminology and in everyday language.

Accordingly, in November 1945, when the main war crimes trial began before the International Military Tribunal, Raphael Lemkin was called to serve as an advisor to Chief United States Prosecutor Robert H. Jackson. In Nuremberg, Lemkin received information about other members of his family who had been murdered during the war, some of them in concentration camps and the Warsaw ghetto. In total, he lost 49 relatives, including his parents who died in Treblinka concentration camp.

For Lemkin, the Nuremberg Trials were only a partial success. The term “genocide” was used in the bill of indictment, but not in the judgement, since crimes against humanity were not recognised as a separate legal category. Lemkin was unable to hide his disappointment at the outcome, and commented on this decision in his autobiography: “The Nuremberg judgement only partly relieved the world’s moral tensions. Punishing the German war criminals created the feeling that, in international life as in civil society, crime should not be allowed to pay. But the purely juridical consequences of the trials were wholly insufficient. [...] The Allies decided their case against a past Hitler but refused to envisage future Hitlers. They did not want to, or could not, establish a rule of international law that would prevent and punish future crimes of the same type”.[9]

Following the unsatisfactory judgement issued by the Nuremberg court, Lemkin continued to fight for the official recognition of the term “genocide” by the United Nations. Finally, after a great deal of effort, he succeeded. On 9 December 1948, the UN General Assembly unanimously approved the “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide”. Lemkin then pushed for the ratification of the convention by appealing to the community of states to agree to the international treaty. The Convention finally came into law on 12 January 1951. Since then, it has been ratified by 147 states. However, the Convention was not applied until a long time later, towards the end of the 20th century, when it was used against the perpetrators of genocide in the former Yugoslavia and in Rwanda.

[6] Ibid., p. 23.

[7] Quoted from Wikipedia, “Raphael Lemkin”, here from S. Power: A Problem from Hell. America and the Age of Genocide, Basic Books, New York 2002, p. 22.

[8] Rafał Lemkin, in: “Dzieje.pl Portal historyczny”, 23/2/2021 (in Polish), URL: https://dzieje.pl/postacie/rafal-lemkin, (last accessed on 8/7/2022).

[9] Frieze, Donna-Lee (ed.): Raphael Lemkin. Totally Unofficial, p. 118.

Hardship in the final years of life

Raphael Lemkin was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize ten times. In 1955, he was awarded the Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany. Although he had fulfilled his life’s mission, he failed to make further progress in his professional life. During the 1950s, he was unable to obtain fixed employment, despite making every effort to do so. He earned his living as a visiting lecturer and gradually fell on hard times. At the same time, he repeatedly asserted that the term “genocide” should be applied to murder in peacetime, such as the famine in Ukraine (“Holodomor”) in 1932 and 1933, which was intentionally triggered by the Soviet government and which led to the deaths of millions of people. During the final years of his life, Raphael Lemkin lived in poverty. During this time, he worked on his autobiography, “Totally Unofficial”, the publication of which he never witnessed. He died on 28 August 1959 of a heart attack sustained on his journey back from his publisher in New York, whom he had contacted to discuss the publication of his memoirs. It was not until 2013 that the Yale University Press published his autobiography, the text of which was edited by Donna-Lee Frieze. The Polish edition, “Nieoficjalny”, published by the Pilecki Institute, appeared in 2018 to mark the 70th anniversary of the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

Monika Stefanek, April 2022

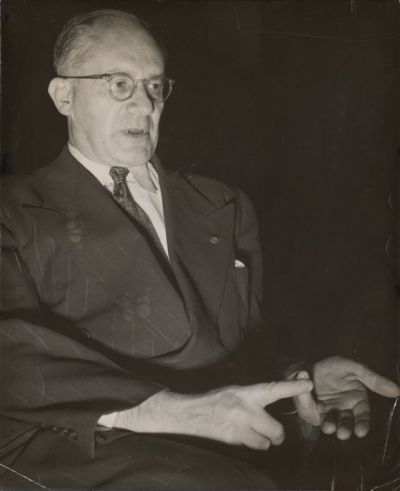

Fragment of an interview with Raphael Lemkin, in: Television programme “U. N. Casebook”, CBS, February 1949, URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F57pgpr_jdw

Lemkin Citizen of the World, audio drama in: UN Audiovisual Library, UN Radio Classics, 1/1/1958, duration: 13:49, URL: https://www.unmultimedia.org/avlibrary/asset/C904/C904/

Lemkin. Świadek wieku ludobójstwa [Lemkin. Witness of the Genocide Century], online exhibition, Pilecki Institute (in Polish), URL: https://instytutpileckiego.pl/pl/wystawy/wirtualne-wystawy/lemkin-swiadek-wieku-ludobojstwa