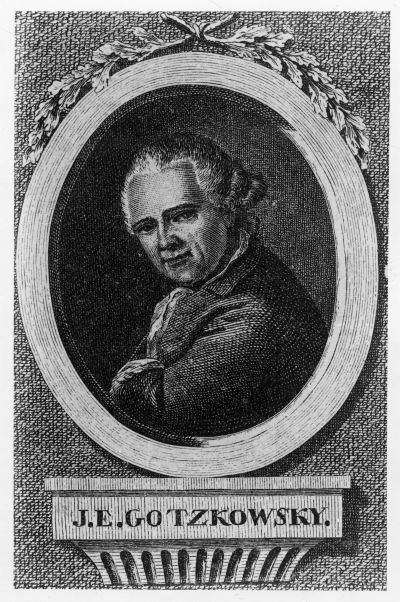

Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky (1710-1775)

In Berlin, the name Gotzkowsky can be found frequently in public life. In Moabit, there is a bridge, a chemist and a street that bear his name. Even a primary school was named after him. But in spite of his undisputed accomplishments for the town, the industrious businessman is not very well known and his Polish heritage even less so.

Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky was born in Konitz in what was Royal Prussia (now Chodnice, the Pomeranian Voivoideship) on 21 November 1710, the second son of Adam and Anna Magdalena, née Abelin. The family was descended from Polish lower nobility and had lived in this area for several generations. But even before Johann was born, his parents lost almost their entire fortune in the Great Northern War (1700-1721) when the Swedish soldiers confiscated all their belongings. In 1711, Johann, who was barely a year old, lost his father. A few years later, like his father before her, his mother died from the plague. Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky remembered his early childhood in documents, which have been preserved, as follows:

“My father was a member of the Polish nobility and known everywhere as an honest man. The terrible wars, which ignited the whole of the North at that time, and which had turned Poland into a stomping ground, crushed my parents completely and deprived them of everything that was theirs. I could hardly have been 5 years old when I lost both my parents to the plague which was raging at the time, and thus, at an early age, I became an orphan.”[1]

Because there was nobody local who could have looked after the boy, and his older brother Christian Ludwig had already moved to Berlin before the death of their parents, Johann Ernst was taken in by relatives in Dresden, where, according to his memoirs, he lived until the age of fourteen without learning to read or write.[2] In 1724, his brother took Johann’s education in hand and sent him to a school for merchants. For six years, Gotzkowsky learnt how to be a merchant in Sprögel’s materials business whilst perfecting his reading, writing and arithmetic. Meanwhile, Christian Ludwig was busy enhancing his prestige in the Berlin merchant guild and, after his marriage to the daughter of the wealthy influential businessman Georg Weißling, progressed to doing business with the royal court. After the business where Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky was learning his trade burnt down, his brother brought him into his company, which sold high-end accessories. Its customers included members of the royal family, including the Queen of Prussia, Sophie Dorothea of Hanover.

The contacts he made during this period would later help the younger Gotzkowsky brother to realise his ambitious plans. It was his acquaintance with Frederick II, in particular, whom the merchant visited in Rheinsberg several times, that would prove particularly useful. The future ruler of Prussia spent his youth there, with Gotzkowsky supplying him with fashion accessories that he sourced directly from the famous Leipzig Trade Fair. The years spent in Rheinsberg are considered the period that Frederick the Great spent preparing for his regency in Prussia. When Frederick II came to the throne in 1740 at the age of 28 after the death of his father Frederick William I, the kingdom was in excellent shape. The state administration was impeccable and the royal treasury was full to bursting. However, from an economic standpoint, the development of production facilities was urgently needed. The king discussed his intentions with his closest confidantes, one of whom was Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky. Shortly after he came to the throne, Frederick II appointed him to search for artists and entrepreneurs who wanted to settle in Prussia and who, above all, had mastered the production of silk.

[1] Schepkowski, Nina Simone: Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky. Kunstagent und Gemäldesammler im friderizianischen Berlin, Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2009, p. 11, URL: https://books.google.de/booksid=ckXnBQAAQBAJ&lpg=PP1&hl=de&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false (last accessed on 11/1/2022).

[2] Schepkowski, Nina Simone: Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky. Kunstagent und Gemäldesammler im friderizianischen Berlin, Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2009.

In 1744, Gotzkowsky was awarded citizenship of the city, which gave him the right to marry. Barely a year later, he married Anna Luise Blume, a daughter of the rich merchant and court supplier Christian Friedrich Blume, who, at the suggestion of his son-in-law, expanded his manufacture to include the production of velvet and silk; two materials which were much sought after at the time, even by the king himself. The early death of his father-in-law in 1746 saw Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky inherit his entire fortune, which helped him rise up to become one of the largest producers of silk. Thanks to his acquaintance with the king, who afforded him operating loans, including for the acquisition of state-of-the-art looms, Gotzkowsky was able to increase production considerably. In 1754, he employed 1,500 people, which at the time was an extremely large workforce and made him the most important representative of his industry in Berlin.[3]

Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky’s wealth grew in tandem with the growth of his company. This allowed the entrepreneur to expand his collection of works by renowned artists. And because the king also appreciated his expertise and extensive contact to artists, in 1755 Frederick the Great commissioned Gotzkowsky to acquire paintings, including Rubens, van Dyck and Tintoretto, for the new gallery in Sanssouci Palace in Potsdam. However, when the Seven Year War broke out in 1756, the king only bought part of the ordered artworks from Gotzkowsky because the budget set aside for them was being channelled into Prussia’s war coffers. At this time, Gotzkowsky’s collection included over 700 works by the most famous European painters.[4]

The entrepreneur also invested his money in real estate with the same enthusiasm he had for art. He owned houses in the most prestigious locations in Berlin, including in the vicinity of Schlossplatz and Potsdamer Platz. At one time, Gotzkowsky had a palais at Leipziger Straße 3 (which was torn down in 1899), on the site of which the new Preußisches Herrenhaus was built at the beginning of the 20th century, which is today the seat of the Bundesrat, the second chamber of the German Parliament.

In the late 1750s and early 1760s, Gotzkowsky was without doubt one of the richest citizens in Berlin. In 1761, his enormous financial resources led Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky, presumably coaxed by the king, to found a porcelain manufacturing facility to make the “white gold” that was so valued at the time. The industry was not entirely unknown to the merchant because, in 1741 shortly after Frederick II came to the throne, he and his brother had already travelled to Meißen to entrust the porcelain factory there with the production of a magnificent table service for the Royal Court, although the identity of the actual customer was kept top secret. The ruler of Prussia wanted to remain anonymous. His rival in the first Silesian War (1740-1742), Frederick August II, Elector of Saxony from the House of Wettin, was not supposed to find out for whom the noble crockery was intended. For this reason, the Gotzkowsky brothers were sent ahead to Meißen. The pattern, which was apparently designed for them, was given the name “Gotzkowsky erhabene Blumen” and is still included in the product portfolio today. In 2015, the dinner service was reissued in the “Limited Masterworks” edition.

[3] Gotzkowsky, Johann Ernst, in: The History of Berlin. Association for the History of Berlin e.V., founded in 1865, URL: https://www.diegeschichteberlins.de/geschichteberlins/persoenlichkeiten/persoenlichkeiteag/459-gotzkowsky.html (last accessed on 12/1/2022)

[4] Luh, Jürgen: Nina Simone Schepkowski: Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky, in: sehepunkte. Rezensionsjournal für die Geschichtswissenschaften, Issue 11, 2011, No. 1, URL: http://www.sehepunkte.de/2011/01/17262.html (last accessed on 12/1/2022)

Prior to Gotzkowsky’s porcelain factory being established, Berlin had only one small factory which, however, was unable to compete with Meißen in terms of quality or decoration. On top of this, Meißen, including the porcelain factory and its warehouse, was besieged and captured by Prussian troops in the Seven Year War so that the richly decorated crockery arrived at the royal tables directly from there. At any rate, Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky was the first to establish a true porcelain factory in Berlin. And because he promised high wages, he soon managed to headhunt the most respected specialists from Meißen. He also managed to acquire the strictly guarded recipe for the manufacture of high-grade porcelain. However, once the new factory started production, the financial situation of its owner deteriorated dramatically. The king, whose war spending had long exceeded all limits, was no longer able to afford expensive purchases. In addition, Gotzkowsky’s finances were already under enormous strain before the factory went into production because, during the Russian siege of Berlin in 1760, he had paid for the subsistence of the Prussian garrison and the relief corps from his own private coffers. When the surrender of the city and its occupation by the Russians and Austrians were no longer able to be averted, he used his negotiating skills to ensure that the toll of 4 million thaler, which the city was supposed to pay, was reduced to 1.5 million. In the end, the toll was just 500,000 thaler, 50,000 of which were again paid by Gotzkowsky himself.[5] Thanks to this personal sacrifice, he rose up to become a prominent citizen of the city and was celebrated as a “patriotic merchant”.

However, this social standing did not save Gotzkowsky, who had largely built his fortune on high-risk transactions, from bankruptcy. At the end of the Seven Year War, he invested in Russian grain. The insolvency of the Amsterdam Bank “Gebroeders de Neufville”, who were supposed to help him finance the purchase of the warehouse, and the withdrawal of business partners from his company, plummeted Gotzkowsky into debt and forced him to sell his possessions. In 1763, the porcelain factory was bought back by Frederick II the Great himself for 225,000 thaler. The king took over all 146 employees and gave the production facility its new name as the Royal Porcelain Factory [Königliche Porzellanmanufaktur (KPM)], the name under which it still trades today.[6]

Gotzkowsky never got his fortune back. To settle his debts with the Russian creditors, he was forced to give up 317 paintings from his collection, which he had spent years building up, to Empress Catherine II, including 13 works by Rembrandt, 11 by Rubens, two by Raphael and one Titian. [7] Some of these paintings are still in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg today. The end of Gotzkowsky’s career as an entrepreneur was sealed in 1766 by the financial crisis. He spent the last few years of his life in poverty and obscurity until he died in Berlin on 9 August 1775, presumably of typhoid.

Monika Stefanek, January 2022

[5] Gotzkowsky, Johann Ernst, in: The History of Berlin. Association for the History of Berlin e.V., founded in 1865, URL: https://www.diegeschichteberlins.de/geschichteberlins/persoenlichkeiten/persoenlichkeiteag/459-gotzkowsky.html (last accessed on 12/1/2022)

[6] History of KPM, in: Königliche Porzellan-Manufaktur Berlin, URL: https://en.kpm-berlin.com/pages/history (last accessed on 12/1/2022)

[7] Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky, in: Wikipedia. The Free Encyclopaedia, 22/7/2022, URL: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Ernst_Gotzkowsky (last accessed on 12/1/2022)