Remigration or return? Back to the old homeland as a Ruhr Pole

Remigration or return? Back to the old homeland as a Ruhr Pole

My name is Patrick Barteit and I was born in 1972 in Oberhausen. I'm a Ruhr Pole. I don't speak Polish. Not yet. The history of my family's emigration to the Ruhr area begins in 1918 in the small village of Orkowo, in the district of Śrem in the Province of Poznan and, after 100 years in Oberhausen, it leads back via Warsaw to Olsztyn in Poland in 2018. This is the story of the Tomczak family. This is my story.

The departure

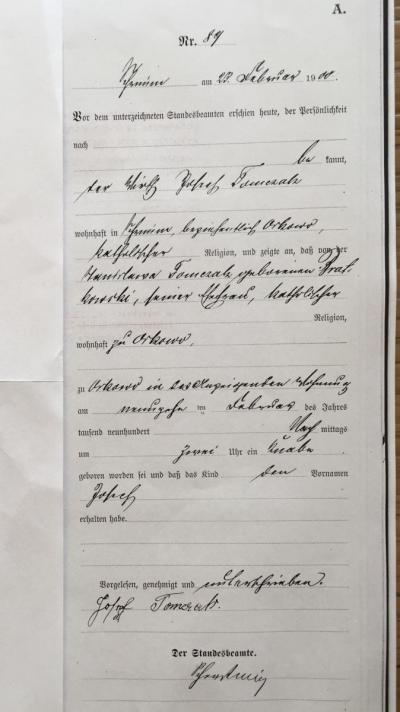

In 1900, my great-grandfather Józef Tomczak was born as the eldest son of Józef and Stanisława Tomczak in the small village of Orkowo on the Warta. He was a Pole, just like his parents, great-grandparents and great-great-grandparents generations before him. That fact was indisputable for everyone in the family. At home the family spoke Polish, like everyone else in the small village. Due to the partition of Poland, however, no independent Polish state had existed since 1795. The Province of Poznan was occupied by Prussia, and the German language was compulsory at school and during visits to the authorities. The Polish population were dubbed "Prussian citizens of Polish nationality" by official channels. As a national minority it was by far the largest section of the population in Prussia. Times were hard, money was short and poverty great. By contrast, in the second half of the 19th century, industrialization in Germany led to a large demand for labour. In particular the Ruhr area attracted workers from Germany and abroad. Coal and steel promised a better future. When he was 18 years old Józef Tomczak also decided to leave the family home and local village to make his way to the Ruhr – like hundreds of thousands of Polish compatriots before him.

The arrival

Arriving in the Ruhr area in January 1918, Józef found a job as a miner at Osterfeld colliery, which belonged to the integrated network Guten-Hoffnungs-Hütte (GHH) (Good Hope Mill). At that time, Osterfeld was an independent municipality in Westphalia until it was merged with Sterkrade and (old) Oberhausen on August 1st 1929 to form the new urban district of Oberhausen in the Rhineland. This was part of a major regional reform of the Rhineland-Westphalian industrial area.

Due to the large number of Poles in the Ruhr area there was a distinct and well-networked Polish community with a very well organized infrastructure. Thus, Józef Tomczak could also find support and helpful contacts within the Polish community and was not left on his own after his arrival. Initially young miners from abroad lived in single dormitories provided by the employer, or they paid a small sum of money to board with private individuals.

Like almost all workers from the East, Józef wanted to earn a lot of money as quickly as possible in order to send some of his wages back home to support his family. What remained was saved. Despite the great distance, he kept up contact with his family. There was regular correspondence with his sister Zofia Stanisława and brother Stanisław. The latter even visited his elder brother in Osterfeld.

After three years working at the colliery, Józef met my great-grandmother Anna Maria Galewska in 1921. Anna's family also came from the Province of Poznan – from the village of Koryta in the district of Krotoszyn. Her parents immigrated to the Ruhr area in 1895. Anna Maria's father Tomasz, my great-great-grandfather, was also a miner at Osterfeld colliery. Tomasz Galewsky and his wife, Maria, could not speak German. They only picked up a few German words from their five daughters who went to school here. The Galewsky family had been living in a colliery house of the settlement Stemmersberg in the municipality Osterfeld since 1903.

Anna and Józef's wedding followed quickly. For her, like many other Polish immigrants, a marriage with a German would have been inconceivable for many reasons. The Poles were called "Polaken" by the Germans and were regarded as second-class citizens. Discrimination against non-German Ruhr Poles was the order of the day. Most Poles therefore took refuge in a Polish parallel society after work, and remained among themselves. Being "foreign" in Germany, having a common language and culture, family pressure and the proximity of the company housing estates prevented intercultural marriage for a long time. Hence Anna Maria's four sisters also had Polish husbands – even from the Province of Poznan. Her oldest sister Pelagia had already returned to Poland in 1919 with her husband.

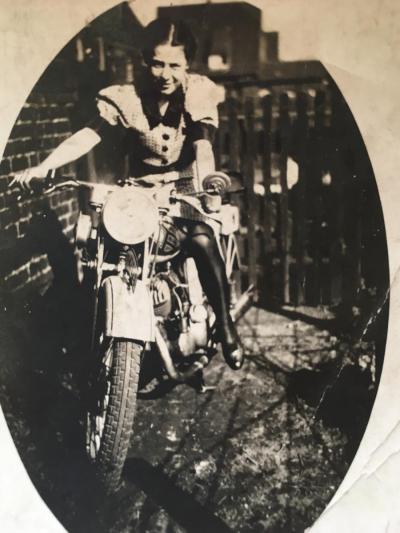

In 1922 Anna and Józef's first child was born. This was my grandmother Henriette. Initially the young family lived in a very cramped room in the home of Józef's parents-in-law, until they were able to move into their own apartment on the outskirts of Osterfeld in 1924. Henriette grew up with her two younger brothers Jan Józef and Edmund. Like many other Polish children in the Ruhr, in the 1930s they spent their summer holidays regularly with their relatives in Poznan. From Oberhausen central station there was a special train for the children of Ruhr Poles, with which Henriette also travelled every summer to her grandparents, the Tomczaks in Poznan. Here, as in Osterfeld, the family ties were very strong. Every weekend the whole family got together: uncles, aunts, and cousins. They ate and drank and danced together. Socializing together was a central aspect of family life.

After finishing primary school my grandmother Henriette completed an apprenticeship as a sales assistant.

At the beginning of the 1940s Henriette met her future husband, my grandfather, at a dance. He was a musician in an orchestra. Apart from drums and trumpet he played the violin. His name was Heinz Johannes Mlinski. He was also a Ruhr Pole, and had been born in Bottrop in 1921. His family originally came from Smolno in the district of Puck, Pomerania. His father, Daniel Paweł Mlinski, was also a miner and worked at the Prosper colliery in Bottrop. In 1945 my grandparents Henriette and Heinz Johannes were married. They had two daughters: their eldest daughter Jutta was born in 1946, and my mother Marlies was born in 1950.

After the beginning of the Second World War there was still regular contact with the Polish Tomczaks in Poznan, and family visits took place until 1943. But with the end of the war and the subsequent Soviet-controlled Communist government in the People's Republic of Poland, all personal contacts between the two families in Poland and Germany ceased for the time being.

Also the Polish language of the family living in Germany had been lost in 1945. Since the Third Partition of Poland in 1795 and the process of "Prussianisation" and "Germanisation" in Germany, the Ruhr Poles had also been exposed to Germanisation pressures right into the 20th century. Despite the fact that the "Prussian Poles" who came from the new Prussian eastern provinces to live in the Ruhr, had German or Prussian citizenship and were well integrated into working life, they were still subject to ethnic and social discrimination. In order to preserve their language, culture and lifestyles, they mostly stayed amongst themselves, and this also included their choice of spouses. Polish language, culture and tradition withstood the pressure of Germanisation for a long time. But things changed during the Nazi era. “With Hitler's accession to power, the situation of the Polish minority deteriorated dramatically. The associations and organisations were "brought into line" and had to defend themselves against interference from outside. Their independent organisations were largely being shattered by increasing anti-Polish agitation, not to mention the abuse and assaults of Fascist bullies. […]. In Oberhausen in 1939 [...] leading members of the Polish minority were arrested and taken off to Sachsenhausen concentration camp”[1] The use of the Polish language among the Ruhr Poles was largely avoided due to fear of assaults. As a result the war and post-war generations hardly learned the language any more. This was also the case with the Tomczak/Mlinski family.

My mother Marlies and her sister Jutta grew up in a colliery house in the municipality Osterfeld in Oberhausen. There were seven persons in one small apartment: with my great-grandfather Józef Tomczak and great-grandmother Anna, my great-uncle Jan Józef and my grandparents Henriette and Heinz Johannes Mlinski. To all extents and purposes there was virtually no private sphere. The family liked to spend the summer months in the back garden. There they kept chickens, planted vegetables and had apple and plum trees.

My mother met my father at the end of the 1960s. In 1971 they were married and moved out of the colliery settlement. I was born in 1972 and remained the only child. The marriage of my mother and my father, Detlef Barteit, marked the first break in „tradition" in the history of our Polish family. The Barteit family was not Polish. They originally came from Lithuania and had immigrated to the Ruhr area via the former East Prussia in 1918.

My great-grandmother Anna Maria died in 1953, and my great-grandfather Józef died in 1976. At the end of 1979, my grandmother Henriette and her brother Jan Józef moved into a modern town apartment. The era of the colliery settlement was over and coal-fired heating was now a thing of the past. Here there was gas heating and an integrated bathroom with a shower and hot water supply.

[1] Netzwerk Interkulturelles Lernen, Geschichtswerkstatt Oberhausen e.V., “Polen im Pütt”. In: Geschichte(n) von Migration in Oberhausen – Hintergründe, Erinnerungen, Dokumente, Jg. November/2007, p.12.

I am now a third-generation Ruhr Pole. I spent my childhood and youth in the Oberhausen suburb of Osterfeld and still live there today. I grew up fully conscious of being of Polish descent, for this was communicated from generation to generation. As early as the age of 15 I was already interested in my roots and began genealogical research, collected all the relevant information and studied the history of Poland and Lithuania. During my time as a student in the mid-1990s I made several trips to Poland. This is how I got to know and love the country and its people. The older I got, the more I became interested in and attached to the land of my ancestors. It was my interest in history, which led me to meet my wife, Joanna, a few years ago. Joanna was born in Olsztyn and has lived most of her life in Poland. She only left Poland on account of our marriage. By marrying a native Polish woman, I, a Ruhr Pole, have closed the circle once more and revived the family tradition. We now have two daughters, one aged three, and the other seven months.

Even before we got married, my wife and I had decided to return to Poland. For my wife it was self-evident, because she never really settled here in Germany. For me, the decision is a real turning point in my life. After more than 100 years of living in the Ruhr area, I shall now return to the land of my ancestors. To my new and old Polish homeland. Friends, acquaintances and relatives ask me why. There are a number of reasons.

I want to give my life a new feel. I want to "decelerate" my life. When we are in Poland I notice how I come to rest, how my body and mind have an opportunity to replenish and regenerate. I have a whole new feeling of being “at home”. This means quality of life for me. For many years now I have completely ceased to feel at home in the Ruhr area, here in Oberhausen. This feeling exists only as a sentimental memory of my childhood and youth.

The structural changes in the coal and steel industry and the associated life styles in the Ruhr area – it was moving into the service sector – slowly led me to throw off my ties to my German “home”. As a child and teenager I had lived through the final years of the coal and steel industry and this was precisely what had made this region so special. Structural change has not been successful. Once the Ruhr area was the industrial heart of Germany; today it is the poorhouse of the nation. City centres and neighbourhood centres have almost disappeared: the streets are badly maintained, as are kindergartens, schools and other public facilities. This change has also ushered in an enormous socio-cultural change. No, my “home” no longer exists here.

However the most important reason for moving to Poland is our children. As parents, we have carefully considered where our daughters have the best chances for a good future. We quickly agreed that this would only be possible in Poland. Poland is a wonderful country, with so much potential and so many opportunities. A country on the move. In Poland, our children will find a well-functioning school system, a homogeneous society with shared values and security as in no other European country.

Our timetable is fixed. In two years at the latest, we would like to have moved the centre of our life to Olsztyn. With its good infrastructure, Olsztyn can offer us everything we expect. In 2016, we completed the first step of the move by purchasing a building plot. Our children are growing up bilingual, so that Polish will not be a foreign language for them, and I am also a keen student of Polish. Unfortunately, for me as an adult it's harder than for the children. I have already received some job offers from a headhunter. But we also have some business ideas of our own.

The way back via Warsaw

However, I have imposed the greatest obstacle on myself. I want to return to my home country as a Pole. I. e. as a Polish – and not as a German – citizen. This is my deepest and most intimate wish, because as a Ruhr Pole I am also a Pole. My wife has Polish citizenship as have our daughters. My primary ambition is for us to be a completely Polish family. My great-grandfather left Orkowo as a Pole, but his parents and siblings remained there. He lived in Germany with German papers, whereas his siblings in Poland had Polish papers from 1918. Was he any the less a Pole for this reason? Today I have contact with the great-grandchildren of my grandfather's brothers and sisters. They all live in Poland, with Polish papers. Nevertheless, we have the same ethnic origin.

After receiving legal advice from a Polish lawyer, I was left with basically only one solution: to obtain proof of my family history. Since I had been doing genealogical research for many years, it would be easy for me to present my pedigree. My application would be submitted via the Polish Consulate in Cologne, which would forward the documents to the voivodship office in Warsaw. In February 2017 I made an appointment with the consul to submit my application. My desire to become a Pole by nationality was a cause of great astonishment because it was more common for Polish citizens to aspire to German nationality. I handed over the application to the consul and attached a large number of birth and marriage certificates, translated by a sworn translator.

Weeks and months passed. In November 2017 I received a letter from Warsaw asking me to provide further evidence. As I was not entirely clear what was missing, my wife telephoned the voivodship office directly. The person in charge was very friendly, and eager to help. He requested the original official birth and marriage certificates of my maternal line, or certified copies, along with further proof that my great-grandfather Józef Tomczak was a Pole from Orkowo, in the district of Śrem, in the Province of Poznan.

That is a solvable challenge. The staff at the registry offices in Oberhausen, Bottrop and Śrem have been very obliging and have sent me all the necessary papers within a few days. Older documents are kept in the archives in Poznan, Kalisz and Gdańsk. These are now also available to me. Here too, I would like to mention how helpful the staff have been. I can now provide evidence of a complete maternal ancestry of Polish ethnicity back to 1800. All the birth names and spouses are of Polish origin, and all the birthplaces before 1900 are located in Poland. This should prove the Polish nationality of my great-grandfather Józef Tomczak.

The deadline for submission of the remaining documents ends in June 2018 and I have compiled everything to the best of my knowledge and belief. The formal decision as to whether my family was and is Polish is now in the hands of the Warsaw authorities.

Patrick Barteit, February 2018

The big reunion

In June 2018 it was finally time. We set off in our caravan to Orkowo, to the town where my great grandfather was born. The exact date was 16 June 2018. More than 100 years after Józef Tomczak had left his childhood home, I was returning there with my family to visit my relatives.

To be upfront from the start, I can say that it was one of the most emotional days of my life. There wasn’t a cloud in the sky and the temperature was already 30 degrees early in the morning. We had been able to park our caravan near the Warta where we had a view out to Orkowo and my family’s fields.

At 10 a.m., we were picked up by my cousin Krzysztof Budzyn. He lives in Śrem and works as an historian. Our journey started in Binkowo, the birthplace of my great-great grandmother Stanisława Tomczak, née Bratkowska. When we got there, we visited the farm that had previously belonged to the Bratkowski family. Today, it is no longer owned by the family.

Then finally, we travelled to Orkowo to my family’s farm. It is a small family-run cow and pig-breeding business. The farm was set up by my great-great-great-grandfather Michał Tomczak and his wife Marianna Skorupska on 9 June 1870. My great-great-grandfather Józef and his wife Stanisława then carried it on. In the 1950s, after Józef’s death, my great-grandfather's sister, Zofia, and her husband Bronisław Pawlisiak took over the running of the farm. Today, the farm is run by Uncle Edward Pawlisiak and his wife Bożena, and their son Sławomir with his wife Renata and their children Dominika and Jakub who all live there.

I can’t really express in words what that first meeting was like. The feelings just kept raining down on me. The people, the farm, the joy, lots of questions, the hot weather, the journey ... I felt like I was in a trance and at times had the feeling that the ground was being pulled from under my feet.

We had brought some old family photos with us from Oberhausen and Aunt Bożena got an old family album out of the cupboard as well. We were all surprised to find that we shared many of the same photos. It appears that in the 1920s, my great-grandfather sent a lot of photos of his children and family from Oberhausen to his parents in Orkowo, and vice versa. Uncle Edward was also able to recall from stories he had heard that my grandmother Henriette used to visit regularly during the holidays when she was a child and a young girl.

The hours we spent together passed in the blink of an eye. Late in the evening, we returned to our caravan. My wife put the children to bed then went to bed herself. I sat alone on the banks of the Warta for quite some time, enjoying the peace and nature and organising my feelings, impressions and thoughts. I was both happy and sad at the same time. Sad because my grandmother Henriette and my great-grandfather were no longer around to see that I was tracing their steps. Happy because, as well as feeling grounded, I also felt as if I belonged. As part of the whole thing, as part of Poland.

Since this first meeting, we have visited the family and Orkowo regularly. The youngest on the farm, Dominika and Jakub, are the same age as our children and get on well together. The plan is that my mother will come with us on our trip in 2021. She would also like to get to know the family in Poland and see the house where her grandfather was born.

As I mentioned at the start, my cousin Krysztof Budzyn is an historian in Śrem. We are related to each other through my great-great-grandmother Bratkowska’s line. He is also very taken with the idea of having my Polish nationality confirmed through formal channels. “Śremski Notatnik Historyczny”, the specialist journal (Number 22) he publishes regularly, ran my family’s story which received a lot of positive feedback. In principle, everyone I have spoken to so far in Poland and who knows the context of my history is in no doubt that I am a Pole.

Mail from Warsaw

On 11 January 2019, I received a registered letter from the Voivodeship's office in Warsaw. My hands were shaking as I opened the letter. My disappointment was enormous. My application for Polish citizenship had been rejected and the reasons given in a detailed letter.

None of the documents or the family record book that I had submitted were considered sufficient evidence. We rang the Voivodeship’s office again so that we could find out in detail the reason for the rejection. The answer is quite simple: According to Polish law, the documents evidencing lineage (birth, marriage) must be issued by a Polish office. My great-grandfather was born in 1900. At this time, the Polish state did not exist. This means that anyone born before 1918 who did not have Polish papers issued after 1918, is, by definition, not a Pole. This is the case, even if their surnames and those of their forefathers are entirely of Polish origin and they were born in what is today Greater Poland.

The highest authority

After the initial shock, it took quite a while for me to process the disappointment. But “Poland is not yet lost”. My grandmother’s favourite saying that she liked to use in difficult situations reawakened my fighting spirit. For my wife and I it was and is absolutely certain that we would like to move our lives back to Poland. Our children are very well prepared for it; they are growing up bilingual so that the move won’t cause any language problems for them.

We thought about what other possibilities there could be. During my research, I came across the Polish Institute in Düsseldorf. This is a facility of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland and, amongst other things, serves the cultural exchange between Poland and Germany. It also takes up historical issues. I wrote a letter to the Institute briefly explaining my situation and the facts of the case. Some time later, my wife and I received an invitation to Düsseldorf. In nan extensive discussion with an employee of the Institute, we were told that the President of the Republic of Poland, Andrzej Duda, can award Polish citizenship. On 23 May 2019, I had an appointment in the Polish Consulate in Cologne. I told them there about my issue and submitted an application for Polish citizenship to be granted through the President. I attached a detailed rationale of my request with the application.

I have yet to receive a response. When I enquired last week, the Consulate told me that there are no deadlines in cases like this and nobody can say when a response is to be expected. My fate once again lies in Warsaw’s hands …

Patrick Barteit, December 2020