From the Sokół club to Dariusz Wosz – Polish sport in Bochum

Bochum was the organisational centre of the Polish-speaking[1] migration to the Ruhr area that characterised the long 19th century in the industrial region and engineered the coalmining district as a vast migration area and Polish “ethnoscape”, an experiential space in the migration process. The city became the heart of the self-organisation of a “Polish movement”[2] which attempted to accompany, moderate and politically articulate the process of immigrating and establishing new social structures and identities. Hundreds of thousands of Polish-speaking people and Masurians[3] from the eastern territories of the German Reich immigrated to the coalmining district before the First World War and, prior to 1914, created a resident population of an estimated 500,000 people, including Masurians[4]. It was not long before the Polish immigrants lived in ethnic residential colonies which changed the face of the cities. They developed a differentiated clubs life, with 875 associations, in which more than 80,000 migrants were organised, and founded a Polish trade union headquartered in Bochum as well as their own Polish-speaking press. The largest Polish daily newspaper “Wiarus Polski” (English "Polish mater or miner") was edited and printed in Bochum. The paper had a circulation of between 10,000 and 12,000 copies and was published by Jan Brejski, a member of parliament and influential politician in the Ruhr area. As a politician, trade unionist and member of numerous Polish associations, Brejski embodied the “Polish movement”. The headquarters of the Union of Poles in Germany was also located in Klosterstraße (which today is called Am Kortländer) in Bochum.[5]

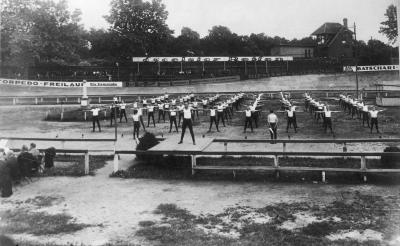

Soon, gymnastics clubs, the so-called Sokół societies, which bore the falcon (Polish “sokół”) in their crest as a symbol of courage and boldness, were also part of the immigrants’ self-organisation. With their processions, gymnastics festivals and club life, the Sokół societies were a fundamental part of everyday life in the Polish community, they were visible to the outside world and, with their connections to the Polish headquarters of the Sokół society in Poznań (Związek Sokołów Polskich w Państwie Niemieckim/Polish Sokół Association in the German Reich) and with their Polish nationalist alignment, they were a provocation for the Germanisation efforts of Prussian-German politics[6]. For this reason, the societies were regarded with suspicion by the Pole monitoring body which had also been established in Bochum.

Although the Sokół societies, which numbered 117 associations prior to the First World War, were the second largest association in the framework of Polish clubs in the Ruhr area after the religious organisations[7], they have been very much neglected in written history. The educated middle-class view of the historiography of the Federal Republic has long failed to attribute much importance to the sporting leisure activities; in the history of the People’s Republic of Poland, the scientific study of the association was frowned upon and prohibited due to the middle-class dominance in the Poznań headquarters and the nationalist alignment.[8]

[1] Between 1772 and 1795, the Polish state was annexed by the major powers Prussia, Austria and Russia and split into three parts (zones). Poland disappeared from the map until 1918. The terms “Polish” and “Poland” need to be understood in this context.

[2] cf. Schade, Wulf, Kużnia Bochumska – die Bochumer (Kader-)schmiede. Bochum als Zentrum der Polenbewegung (1871-1914), in: Bochumer Zeitpunkte, 17 (2004), p. 3-21 (https://www.kortumgesellschaft.de/tl_files/kortumgesellschaft/content/download-ocr/zeitpunkte/Zeitpunkte-17-2005OCR.pdf, accessed on 27/12/2020).

[3] The Masurians, who are often confused with Poles, present a specific challenge in themselves which will not be dealt with here. The ethnic group, which mainly hailed from the Eastern Prussian districts of Ortelsburg, Neidenburg and Allenstein, was an amalgamation of an ethnic majority of Poles, assimilated Germans, Huguenots, Scots and Salzburgers. They spoke an old Polish peasant dialect, were Protestants and traditionally pro-Prussia. For the history of Masuria and the Masurians cf. Kossert, Andreas, Masuren: Ostpreußens vergessener Süden, Berlin 2001.

[4] For the uncertainty around the numbers and their discussion, cf. Bleidick, Dietmar, Bochum, das institutionelle Zentrum der Polen in Deutschland, in: Bochumer Zeitpunkte 33(2015), p. 3-9, here p. 3. https://www.kortumgesellschaft.de/tl_files/kortumgesellschaft/content/download-ocr/zeitpunkte/Zeitpunkte-33-2015OCR.pdf, accessed on 27/12/2020).

[5] For the significance of Bochum for Polish-speaking immigrants, again cf. Bleidick 2015.

[6] A detailed account of the history of this organisation, its social and political role for the migrants in the industrial region in the context of the social-historical development can be found in Blecking, Diethelm, Sport, Fußball und Migration im Kohlerevier. Polnische Migranten im Ruhrgebiet und in Nordfrankreich, in: Hüser, Dietmar/Baumann, Ansbert (publ.), Migration/Integration/Exklusion. Eine andere deutsch-französische Geschichte des Fußballs in den langen 1960er Jahren, Tübingen 2020, p. 83-111.

[7] For the club framework cf. Blecking, Diethelm, Polen/Türken/Sozialisten. Sport und soziale Bewegungen in Deutschland, Münster 2001, p. 54.

[8] For this administrative construction of history in People’s Poland cf. Blecking, Diethelm, Die Geschichte der nationalpolnischen Turnorganisation “Sokół” im Deutschen Reich 1884-1939, Münster (2nd edition) 1990, p. 23.

In Bochum, Polish national activists, such as Jan Brejski mentioned earlier and the editor of the “Wiarus“ Stanisław Kunca operated as members of the Sokół society. The gymnastics clubs have been part of the Ruhr area since 1899. An increasing tendency of the Polish mining folk “to clash” with the administration, which let to the bloody “Herne riots” in the same year, motivated the Polish community to close a gap in their organisation framework.[9] They became part of the federation which organised associations in West Prussia and Silesia, in Berlin and in the Ruhr area right up to northern Germany, and mobilised them towards Polish nationalism. There were five territories in Rhineland-Westphalia. The clubs in Bochum belonged to the Rhenish-Westphalian territory, the Wattenscheid associations to the Rhenish territory, which was headquartered in Wattenscheid, and Langendreer, and Gerthe belonged to the Westphalian territory. Within what are today Bochum’s city boundaries, there were around 12 Polish Sokół societies in 1910: Bochum, Altbochum, Wiemelhausen, Riemke, Bochum-Grumme, Bochum IV, Bochum VII[10], Wattenscheid, Linden-Dahlhausen, Weitmar, Langendreer, Gerthe. As well as having a gymnastics operation, which was aligned with the principles of German gymnastics, the Polish gymnasts also intended to promote activities for the good of Polish national cultural education. Around 450 members were registered in the 12 clubs, although the number of active members was between 50 % and 70 % lower. As with the German gymnasts of the pre-March era and the 1848 revolution, the organisation’s pledge was often a statement of a national political attitude, not always necessarily of the willingness to engage in physical training. Female members were not organised in any of the societies and only the Wattenscheid Sokół society actually practised gymnastics in a gymnasium.[11] Just like the socialist sportsmen of the working classes, the Polish-speaking immigrants in the Wilhelmine class state had little access to municipal resources. The majority of the migrants were male. The Prussian Law on Associations of 1850, which was only superseded by the Reich’s Law on Associations in 1908, forbade women from becoming members in political associations, which is what Sokół organisations were considered to be. After 1908, women were, in principle, allowed to be members, however the national Catholic conservative structure of the Polish community continued to restrict their activities. This is where Prussian repression, the demographic structure of migration and conservative Catholicism excelled in constructing women-free spaces.[12] Since the organisations were also considered “political” within the meaning of the Reich’s Law on Associations of 1908, they were forbidden from organising youth gymnastics. This barrier severely restricted the mobilisation and recruitment possibilities of the Sokół societies.

The sporting operation of the Sokół organisations was restricted to the German gymnastics mentioned, and only rarely were light athletics and group gymnastics permitted. The group exercises had to be dictated by the head office and were often underscored by patriotic music, which was important for organising festivals and processions. Recreational activities, such as football, hardly ever took place. Competitions with German associations were not allowed. Socio-psychologically, the Sokół societies were both a place of retreat and a means of mobilisation for the community of migrants that had been so affected by acculturation problems and disintegration tendencies.

The fear of anti-German, national political activities by the Sokół gymnasts, a fear stirred up by the authorities, led time and again to public activities being prohibited. This meant that the territories occasionally held their territory meetings, the so-called “zlot”, which semantically denoted the flight of the falcon, in Winterswijk in Holland. However, despite a few radical statements made by Sokół officials in American newspapers, these fears of disloyalty proved unfounded. Things became serious at the beginning of the First World War. In February 1917, three years after the outbreak of war, the Rhenish-Westphalian territory, to which the majority of the Bochum associations belonged, summarised the situation in a submission to the Bochum police commissioner as follows: “At the beginning of the war, Territory X of the Polish gymnastic clubs here had around 1,800 members. According to our statistics, 1,152 members were immediately called up following the start of the war.” The submission continued to talk about the price of this loyalty to Prussia and the German Reich: “Up to now (that is until 1917, D.B.), 142 Polish gymnasts from our territory have died a hero’s death and 91 have been awarded the Iron Cross. All of them have loyally fulfilled their military obligations with dedication, to which the many promotions to NCO also bear witness. The gymnastic training in our clubs stood them in very good stead in enduring the stresses of war.”[13]

[9] Blecking, 2001, p. 43-44.

[10] The somewhat odd count is due to the fact that associations quickly disbanded again, particularly during the first phase of establishing the Sokół in the coalmining district.

[11] Statistical data on the Sokół societies in Bochum in Blecking, 1990, p. 231-233.

[12] It should not be forgotten that the German Football Association (DFB) was a women-free space until 1970.

[13] Cited from Blecking, 1990, p. 176-177.

The German defeat in the First World War led to a complete change in the Polish community’s situation in the coalmining district. After the end of the war, the founding of a national Polish state in November 1918 changed the latitude of the Polish minority: As they began to migrate to Poland, Northern France and Belgium, their numbers halved up to 1929. And the Polish national alignment was no longer an appropriate political option. Sport, and of course football, found their way into the gymnastic organisation. In the 1920/21 season, football was already being played in 52 clubs. On 18 December 1921, the first final of the Sokół football championship was played in Recklinghausen; Castrop defeated the Bochum Sokół club Linden 3:2.[14] In January 1927, the Polish athletes succumbed to the political situation and deleted the words “Polish” and “Sokół” from the club names. The organisation was now operating under the name ”Association of gymnastics and sporting clubs from Westphalia and the Rhineland” and playing matches against German clubs.[15]

Integration into German society culminating in assimilation now appeared to many in the community a rational and sensible choice. Membership of the football club was a practical course of action, particularly in the coalmining district. In the 1937/38 championship round, there were 68 players with Polish root names in the teams in the Westphalian and Lower Rhine district leagues.[16] However, the collapse of civilisation resulting from the National Socialist rule soon meant the end of organised Polish sport and of Polish organisations throughout Germany. In the summer of 1939, their premises in Klosterstaße in Bochum were occupied and their assets confiscated[17]; significantly, the final liquidation was governed by an order from the “Ministerial Council for the Defence of the Reich” on 27 February 1940[18]. Officials, some of whom were from Bochum, were murdered during the war or died in the concentration camp.[19]

After the Second World War, players in the German national team who were from the Ruhr area and had Polish-sounding names were then part of football folklore and the anecdotal stories perpetuated by sports journalist, but without any real recollection of historical events. In a fragmented and unsystematic way, the history of segregation and integration, which are bywords for the historical reality of Polish sport in Bochum, became a chapter in a sugar-coated narrative that assumed that migrants and the resident population lived together without conflict during shared football matches. In this harmonised form, the history of the Polish minority also became part of the political discourse.[20]

A new phase of Polish players participating in football in Bochum and in football in the Ruhr area then heralded the belated introduction of professional football and the founding of the Bundesliga in the 1963/64 season. The lifting of the ban on women’s football in 1970 was also part of this urgently needed modernisation of German football. Since the 1950s, women in the coalmining district had organised clubs, matches and even a “national team”, none of which were “legal” in the eyes of the DFB. These women also included women from Masuria and Polish immigrant families, like Brunhilde Zawatzky from Dortmund and Lore Karlowski from Essen.[21] Now any male and any female who had talent could actually get involved. That is why, at the beginning of the 1970s, the proportion of workers among the elite footballers was as high as the proportion in society for the first time[22], the myth of “working-class sport” football was at least partially redeemed. Salaried football made this possible. At the same time, the German market began to attract foreign professionals, including Polish players. Since the end of the 1980s, the Polish state has issued permits for a career in the West, some athletes also defected to the West without these permits during overseas visits.

[14] Blecking, 1990, p. 195.

[15] Blecking, 1990, p. 197.

[16] cf. for this phase Blecking, Diethelm, From the “pit” to the professional league: Poles and Masurians in Ruhr area football (https://www.porta-polonica.de/en/atlas-of-remembrance-places/pit-professional-league-poles-and-masurians-ruhr-area-football, accessed on 26/12/2020)

[17] Schade, Wulf, Verkrüppelte Identität. Polnische und masurische Zuwanderung in der Bochumer Geschichtsschreibung, in: Bochumer Zeitpunkte 23 (2009), p. 25-51, here p. 34 (https://www.kortumgesellschaft.de/tl_files/kortumgesellschaft/content/download-ocr/zeitpunkte/Zeitpunkte-23-2009OCR.pdf, accessed on 27/12/2020).

[18] Blecking, 1990, p. 207, note 3.

[19] Schade, 2009, p. 33-34.

[20] Positive definitions of sport as a vehicle of integration with recourse to the “example” of the “Ruhr Poles” can be found when Helmut Schmidt was Chancellor, Wolfgang Schäuble was Minister of the Interior and Johannes Rau was President of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia. See Diethelm Blecking, “Sport and Immigration in Germany”, in: The International Journal of the History of Sport, Vol. 25(2008), p. 955-973, here p. 956 and p. 967, Note 10.

[21] cf. with further literature Blecking, Diethelm, Die Nummer 10 mit Migrationshintergrund. Fußball und Zuwanderung im Ruhrgebiet, in: Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte 1-3(2019), p. 24-29, here p. 28-29 (https://www.bpb.de/apuz/283266/fussball-und-zuwanderung-im-ruhrgebiet?p=all, accessed on 29/12/2020).

[22] Eisenberg, Christiane, “Deutschland“, in: Eisenberg, Christiane (publ.), Fußball, soccer, calcio. Ein englischer Sport auf seinem Weg um die Welt, Munich 1997, p. 115-116.

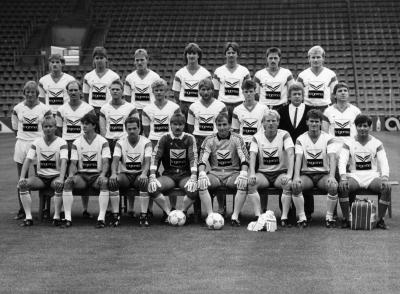

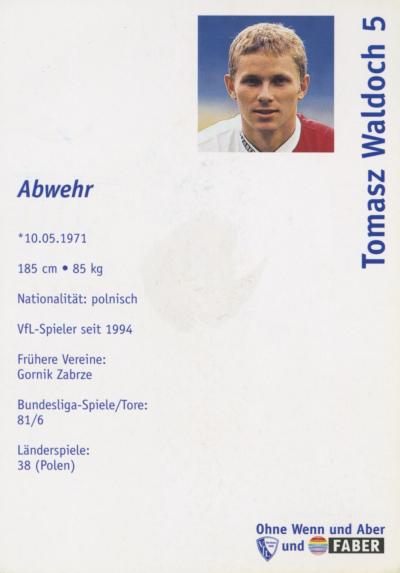

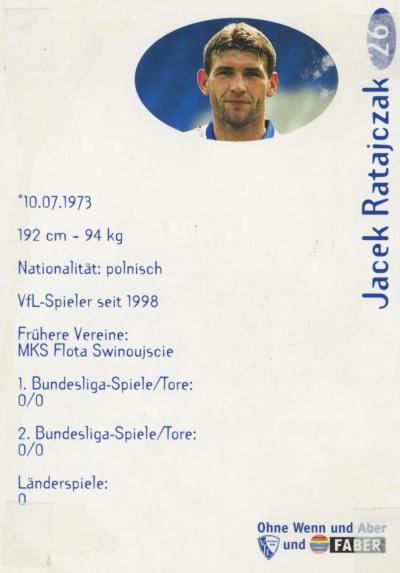

In the Bundesliga years since 1963, nine Polish athletes have played for VfL Bochum. It is no coincidence that Andrzej Iwan (1987-1989), Tomasz Waldoch (1994-1999) and Henryk Bałuszyński (1994-1998) three of the first four Polish players from Zabrze, the heart of the Upper Silesian mining region, came to Bochum. Their club Górnik Zabrze proudly bears the word “Górnik” (English “miner”) in the name.[23] For the fans, these players were players for the “Pott” [coalmining area] who were considered to be grafters and have “coal in their DNA”. This is because the rise of “Górnik” in Silesia was closely connected to the coal industry.[24] Waldoch, who later became a dual DFB Cup winner with Schalke 04, and Bałuszyński played during the most successful period when Bochum finished in fifth place in the final table in the Bundeliga in 1997 and earned a place in the UEFA Cup. Bałuszyński, who died at an early age, scored the first Bochum UEFA Cup goal of all time against Trabzonspor. Maciej Śliwowski (1990/91) also ranked as one of the first Poles to wear a Bochum kit. He was followed by Andrzej Rudy (1995/96), who had settled in the West “illegally” in 1988 and called Udo Lattek “the Polish Beckenbauer”[25], then Jacek Ratajczak (1998-2000), Thomas Zdebel (2003-2009), Marcin Mięcel (2007-2009), Piotr Ćwielong (2013-2016) and Paweł Dawidowicz (2016/2017).[26]

The Bochum icon Dariusz Wosz, who played for VfL between 1992-1998 and 2001-2007 and scored 41 goals, is not an “authentic” Pole despite his Sarmatian name. Instead, he comes from the German minority in Silesia. He came to Halle and to the GDR national team as a migrant during unification, then to Bochum and then to the German Federal national team for whom he played 17 times.[27] Wosz currently holds various roles at the Bochum club.[28]

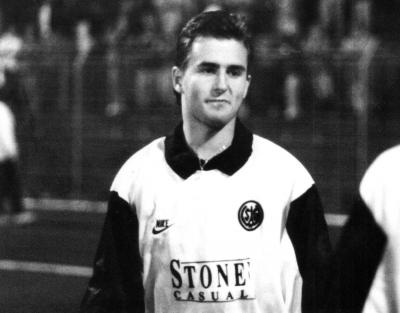

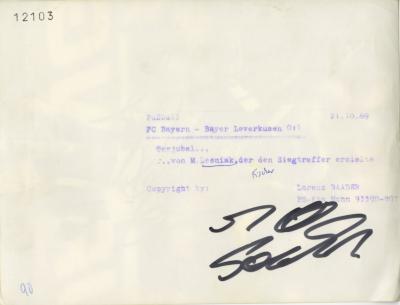

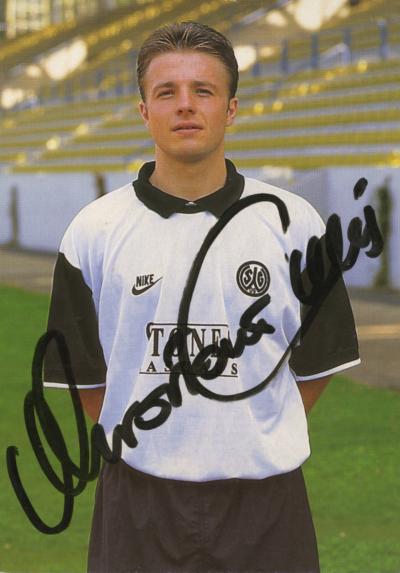

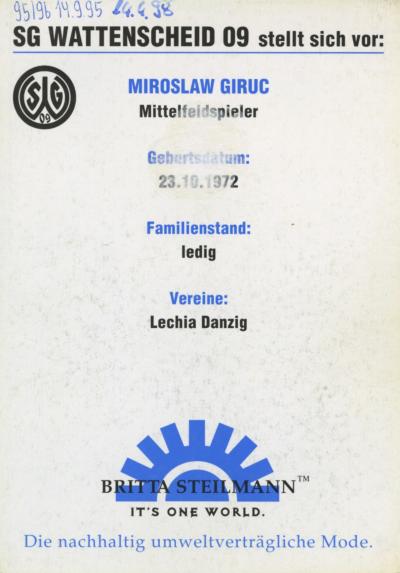

Marek Leśniak became a similar legend for the second Bundesliga club in the Bochum city area, SG Wattenscheid 09. He scored 25 goals as striker between 1992 and 1995. In 1988, Leśniak was the youngest player to be released by the Polish Administration to play professionally in the West. The country needed currency desperately.[29] In 2010, he returned as trainer for a few months. Other signings from Poland included Mirosław Giruc (1994/95), Michał Probierz (1995-1997) and Krzysztof Kasak (2013/2014).[30]

The history of Polish sport in Bochum and Wattenscheid, as in the entire Ruhr area, reflects the history of the Polish and Masurian migration, and consequently the identity issues of the migrants who frequently defined themselves as Poles for the first time in Rhineland Westphalia as a result of external attribution and then through their own self-attribution. Three generations, which were severely affected by secular catastrophes, such as the two world wars and the Nazi dictatorship, which was profoundly hostile to Poles, set off on a tumultuous journey to a life in Germany. In the process of the emigration policy and the globalisation of elite football, athletes born in Poland came from the German minority, like Dariusz Wosz, but after the political shift the majority who came to Germany as professionals were Polish players. Like the Bochum professionals Tomasz Waldoch and Henryk Bałuszyński, they perpetuated the myths and legends of football in the Ruhr area[31], which lives from the relationship between regional concepts of identity and the field sport with its incarnate protagonists.[32] Today, it is estimated that there are around 2 million people with a Polish family background living in the Federal Republic; that constitutes around 2.5 % of the population.[33] The story of their immigration, but also of their sporting history[34], has become a vital and influential component of German history and of the history of the city of Bochum[35].

Diethelm Blecking, January 2021

[23] The first Polish player in the Bundesliga, Piotr Słomiany, who played for Schalke from 1967-1970, also switched from “Górnik” to the coal-mining district. (https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/atlas-der-erinnerungsorte/aus-dem-puett-die-profiliga-polen-und-masuren-im-ruhrgebietsfussball, accessed on 26/12/2020).

[24] Regarding football in Silesia and Górnik Zabrze see Radoslaw Zak, Der Fluch des schwarzen Goldes, in: Ballesterer Fußballmagazin 149 (2020), p. 17-21.

[25] Urban, Thomas, Schwarze Adler/Weiße Adler. Deutsche und polnische Fußballer im Räderwerk der Politik, Göttingen 2011, p. 154, more information about his career in the West which was also of interest to the Boulevard p. 153-157.

[27] For more on Wosz, see Urban, 2011, p. 161-163.

[28] https://www.vfl-bochum.de/news/uebersicht/verein/alles-gute-dariusz-wosz/ (accessed on 27/12/2020).

[29] cf. Urban, 2011, p. 152.

[31] For the myths and legends of the Ruhr area and the role of football, see the interview with Diethelm Blecking, in: Ballesterer Fußballmagazin 149 (2020), p. 29-31 and Blecking 2019, p. 29.

[32] cf. Stefan Goch, Zwischen Mythos und Selbstinszenierung: Fußball im Ruhrgebiet und das Image der Region, in: Westfälische Forschungen 2013, p. 103-118.

[33] With regard to this evidence that has barely been registered and to the full history of this large population group cf. Loew, Peter Oliver, Wir Unsichtbaren. Geschichte der Polen in Deutschland, Munich 2014.

[34] The catalogue published for an exhibition at the Westphalian State Museum of Industrial Culture in 2015 is a useful introduction to the relationships between migration and football: LWL-Industriemuseum (publ.), Von Kuzorra bis Özil. Die Geschichte von Fußball und Migration im Ruhrgebiet, Essen 2015.

[35] As far as the history of Bochum is concerned, however, Schade, 2009, points out the deficits in the way that its history is written and communicated. In this context, he identifies continuing stereotypes and sees “the portrayal of the Masurian and Polish immigration characterised by omission or superficiality, and often by negative stereotypes as well, with only very few exceptions.” (p. 51).