On the trail of art after the horrors of Auschwitz. Dispatches from a study trip.

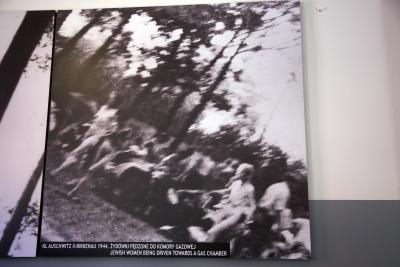

According to the former President of the German Parliament Prof. Norbert Lammert, “[…] helping to find a solid position for the artistic-aesthetic confrontation with our country and our history”[1] is the reason why the German Parliament decided to house the “Birkenau” series of paintings. The four paintings were created by the artist Gerhard Richter. They are based on four photographs that were secretly taken by prisoners in the Birkenau camp. Although blurred in parts, they show scenes of violence and terror. They are testimony to and evidence of the crimes committed by the National Socialists against humanity.

The confrontation with National Socialism has occupied Richter for a long time, and he was unable to shake the impact of the historical photographs taken in 1944. He decided to work on them as a piece of art.[2] A glance at the history of art shows that the artistic confrontation with Auschwitz and the Holocaust has been and continues to be a controversial issue. Is it legitimate to use art as a vehicle for processing a crime as heinous as this? This question was the starting point for the study trip organised by the International Association for Education and Exchange (IBB) and Porta Polonica. It is worth mentioning at this point that, even after a week of intensive confrontation with the painting series, the participants in the study trip, which we called “ ‘Birkenau’ by Gerhard Richter – A Site Visit”, weren’t able to find all the answers to this (and other) questions.

[1] Online services of the German Federal Parliament: Gerhard Richter presents the “Birkenau” series of paintings to the Federal Parliament, URL: bundestag.de/dokumente/textarchiv/2017/kw36-richter-birkenau-525720, last accessed on 17/10/2019.

[2] More information can be found in the article “‘Birkenau’ by Gerhard Richter” on the page: https://www.porta-polonica.de/en/atlas-of-remembrance-places/birkenau-gerhard-richter,last accessed on 19/12/19.

Station 1: Berlin or the journey starts in the present

It was humid on this September day in Berlin. The weather seemed to be saying that the twelve members of the study group have a challenging few days ahead of them. In just under a week, the group will cover 600 kilometres and talk about the relationships between Auschwitz and art at three locations – Berlin, Oświęcim and Kraków[3]. What kind of people found themselves in a seminar room behind the Invalidenpark in Berlin in the incredible heat of summer? Some come from the culture sector, others work at memorials or in education, and are there to gather input about how the culture of remembrance is handled or are interested in (art) history. The majority of them has never been in the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum before.

The first discussion in the seminar room revolved around key phrases, such as “sensitivity of the site”, “interest in art”, “culture of remembrance” and “moral obligation”. Some members of the group also had a personal interest in the place or the stories connected to it, including the persecution of homosexuals. The participant’s all had different levels of knowledge on the subject. This was addressed by two presentations about Poland covering the period between 1933 and 1945 and the history of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp.

The second item on the day’s agenda took the group to the very heart of German democracy: The Reichstag building, the seat of the German Federal Parliament. After Dr Jacek Barski, the Head of Porta Polonica, had given a few introductory words about the artist Gerhard Richter, touching in particular on his work “Birkenau”, the participants had time and space to get together and ask some more questions. They subjected the digital versions of the pictures that were hanging there to close examination: The four large-format paintings hang one above the other and comparatively high up in the visitor foyer – a few groups of people walk past them to get to the plenary hall. Very few visitors appear to look at the paintings. A few discussions break out, including about the way the paintings are presented. These discussions continue during the shared evening meal and remain an ongoing topic for the rest of the week. The fact that the pictures hang in the German Parliament and thus in the heart of German democracy is testimony to their political relevance. But who decides how and in what way the Holocaust is remembered?

The group also critically considered the fact that the photographic templates for Gerhard Richter’s work hang in a different corridor in the visitor foyer. The implications of the painting series can only be clearly identified when the photographs are exhibited directly next to the paintings. For this reason, the group found the way the images are currently presented somewhat questionable: Do the pictures and consequently the transported content get lost?

[3] The place names used below indicate the political affiliation of the place. Where the name Oświęcim appears, it indicates the town under the control of the Polish government.

Station 2: Oświęcim or Art is documentation is emotion

The first station of the journey was able to be discussed in detail during the long bus journey from Berlin to Oświęcim. Today, this town in Lesser Poland is known for the German National Socialists having operated the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration and extermination camp on the western edge of the town from 1940. The town is closely linked to the concentration camp, which, in the public consciousness, has come to represent the Holocaust and the National Socialist crimes against humanity.

However, the German-Jewish-Polish story of the town did not begin when the camp was built in 1940, which is why the group decided to visit the town with its town centre and castle dating back to the middle ages first. This is where you find the Centrum Żydowskie w Oświęcimiu (Jewish Centre in Oświęcim) with its Chewra Lomdei Misznajot Synagogue, which is a meeting place, place of prayer and information space rolled into one.[4] During the tour, the group learnt about Jewish settlement dating back to the 16th century and the relationship of the Jewish population with the town, which they called Oshpitzin. They also heard about the town’s dark chapter, with the beginning of the Second World War and the occupation of the region by the German armed forces, and ultimately of the systematic extermination of more than one million people in the Auschwitz concentration camp from 1941. The last Jew to live in Oświęcim died in 2000. Since then, there has been no separate Jewish community in the town.[5] Today, the people who come to the synagogue to pray are tourists and visitors to the town, predominantly visitors to the memorial. The group was visibly moved by everything that they heard; particularly about events in recent history. Numerous documents from the inhabitants provide insights into the thoughts and feelings of their owners.

The second day began very early and was misty. The aim was to go to the memorial site. During the tour, the group was given an insight into the structure of the camp, the living conditions and the murder of the prisoners in the concentration camp. But before the group arrived at the camp, Bartholomäus Fujak, a member of the IBB pedagogical staff, and the bus driver from the town, drove them to the affiliated district of Hamęrze. The journey took them past sleepy houses waking in the morning light and past the greenery of late summer.

A few minutes later, the group stopped in front of a Franciscan church where a real gem was waiting: an exhibition of the works of the former camp prisoner Marian Kołodziej. Kołodziej worked through his experience in the camp in numerous pictures. He was one of the first to arrive at Auschwitz and he survived.[6] The pictures are pencil and graphite drawings drawn on different sized backgrounds. The exhibition is housed in a narrow cellar vault. The light reveals the distorted , haggard features of so many prisoners who, as shadows of their former selves, are often contrasted with the SS members, who are portrayed as wild animals. Several portraits show Kołodziej himself, who can be recognised by his tattooed prisoner number: 432. Kołodziej did not just want to his pictures to bear witness, he also wanted to give the prisoners of the concentration camp their identity and their existence back. After the tour, the participants had some time to go through the exhibition on their own. In the conversations that followed on the way to the bus and during the journey to the memorial, the general mood fluctuated between feeling overwhelmed at the sheer number of impressions they were left with and their admiration for the artist.

[4] More information can be found on the Centre’s website: https://ajcf.pl/en/museum/, last accessed on 7/1/2020.

[5] cf. Olga Mielnikiewicz: Oświęcim. Historia społeczności, Link: https://sztetl.org.pl/pl/miejscowosci/o/546-oswiecim/99-historia-spolecznosci/137813-historia-spolecznosci, last accessed on 7/1/2020.

[6] See the detailed portrayal of Kołodziej, the survivor and artist: Monika Mokrzycka-Pokora: Marian Kołodziej, in: culture.pl, Link: https://culture.pl/pl/tworca/marian-kolodziej, last accessed on 7/1/2020.

The group then made their way to the site of the Państwowe Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau (PMO) (Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum). During the tour they passed through the exhibition: The exhibition doesn’t just cover the story of the camp’s history, spatially it also covers the whole area of the camp. The red brick buildings of the barracks glowed in the afternoon sun – it is in remarkable contrast to the story that took place here which is displayed for all to see. The rooms were all filled with different groups of visitors. The “highlights”, if you can call them that, included the rooms housing the collections of personal artefacts belonging to the prisoners, which were taken from them when they arrived at the concentration camp. The mountains of suitcases, shoes and combs, some of them labelled with the owner’s name, affect the participants on an emotional level. What left a particularly lasting impression was the shorn hair of the prisoners which is displayed as a seemingly endless pile.

Other aspects include the crematorium and block 11 (the death block). Traces of the prisoners can be found in the photographic portraits, in drawings, and in their belongings.

The tour of Birkenau, three kilometres away, was in stark contrast to the tour of the actual site of the main Auschwitz camp. Against the narrow alleys and the row upon row of brick barracks at Auschwitz, the expanse of Birkenau seemed even more enormous. The few wooden barracks there served only to reinforce the impression of incredible size. But traces of the prisoners can be found here too; in carvings or paintings made by the prisoners in the wooden walls of the barracks. Traces can also be found in the former personal effects stores, which were referred to in the language of the camp as “Canada” and were where the new arrivals had to surrender their worldly goods.[7]

The time in Birkenau was particularly important for the group when it came to Gerhard Richter and his series of paintings: They visited the place where the secret photographs were taken over 70 years ago and were able to gain an impression of the whole area, which lies almost peacefully within the birch trees. Information boards are a reminder of the crimes that were committed here and refer to the photographs that Gerhard Richter used in 2014 as the template for his artistic analysis. The group found that the thematic circle of the study trip closed here, if it hadn’t already.

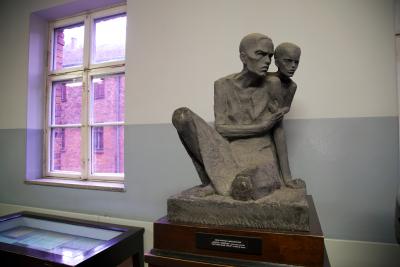

As well as taking the tour, the members of the study group were also given insights into the art collection at the memorial. This is not part of the permanent exhibition, but can be booked separately.[8] Artworks from four different categories can be found there: legal commissioned pieces in the camp context, semi-legal pictures for private use (mostly by SS men), private and illegal works and works that were produced after the war. The memorial has thousands of objects, some of them too valuable in an idealistic and politically commemorative sense for them to be exhibited. These include works of art by professional artists and by amateurs, but also art that was created in secret and which documents the suffering of the prisoners and serves as an outlet for them. Works commissioned for the SS commanding officers and their men are also preserved. They are preserved and exhibited just like the portraits of Josef Mengele’s[9] victims that had to be drawn.[10] But it begs the question, are these objects then art? This is a question discussed by the guide and members of the group in the face of such questionable objects. But the real question is actually - by what benchmarks do we measure art? By the financial value or the type of technique used by the artist? Perhaps, as the staff member at the memorial suggests, you have to see the art objects, irrespective of what category they come from, as documents of the time?

[7] Cf. Israel Gutman, Michael Berenbaum: Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp, Washington D.C 1994, p. 251f.

[8] Cf. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum: Wystawa sztuki w byłej kuchni obozowej, Link: http://auschwitz.org/muzeum/zbiory-historyczne/wystawa-sztuki-w-bylej-kuchni-obozowej/, last accessed on 7/1/2020.

[9] Josef Mengele (1911-1979) was the camp doctor for the so-called gypsy camp and for the women’s camp. He was involved in the selection process and sent thousands to their death. He also carried out pseudomedical experiments on camp prisoners which frequently had fatal consequences. After the end of the Second World War, he managed to flee to South America under a pseudonym. Cf. Franz Menges: Art. Mengele, Josef, in: NDB 17 (1994), p. 69-71.

[10] More information on the types of exhibit can be found at: http://auschwitz.org/muzeum/zbiory-historyczne/sztuka/, last accessed on 7/1/2020.

Overall, the group spent three days in Oświęcim and in Auschwitz-Birkenau. The many impressions gained throughout the trip were dissected during the discussions every evening which were, of course, about art but also about the memorials, like the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. But in general – just like in Berlin – the conversations were about how we deal with the memories of the Holocaust. Keywords, such as “histotainment”[11] were mentioned: The memorial in Auschwitz gets a lot of visitors. In view of the amount of people interested in seeing it, the group wondered what reasons people have for visiting the museum. Does historical consciousness have a part to play or is the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum just another “must-see” on the list of tourist activities for southern Poland? Who has access to historical knowledge and authentic locations anyway? Should we judge people who come with their family and (small) children and who can’t grasp the significance of the place? The discussions also turned to the type of exhibition, the structure and funding body of the memorial and to how the history at the authentic site, which is an emblem and symbol for the horror of the National Socialists, is transported. Contrary to the expectations of many in the group, the art exhibition in Hamęrze was able to showcase the horrors of Auschwitz much more vividly than the authenticity of the actual place. Of course, that doesn’t make it an either-or question between the authentic site and the art exhibition, but it does show the ability of art to move people emotionally.

Even greater than the question of what role the authentic site of Auschwitz plays, is the question posed right at the start in Berlin: Is art allowed to do that? What differentiates the works of Kołodziej and Richter? Whilst one had to go suffer Auschwitz himself, the other looks at the Holocaust with retrospective anguish. One wants to restore the identity of those affected and bear witness, the other wants to give solace. Whilst the images by Kołodziej create a vivid experience, it’s the context that’s crucial for the series of paintings by Richter. The consensus of the group was that the inherent message can only be understood when viewed alongside the photographs from 1944. So this then raises the question again as to how the Holocaust is to be commemorated in public spaces and what role the site has in doing this. Could Kołodziej’s pictures work outside the Centre as well? In the German Parliament, for example, instead of the Birkenau series? A heated discussion arose about the quality of artistic work, of the appropriateness of artworks on the subject of the holocaust and who decides what qualitative art is. Ultimately, they all agreed on the following: Everyone has to make their own decision as to whether art is able to broach the issue of Auschwitz.

[11] What’s meant here is the growing event culture around media with historical content.

Station 3: Kraków or Epilogue

After a few varied, informative but also exhausting days, the group’s journey ended just one hour away in Kraków, the former royal city. The old town with its tourists seems hundreds of light years removed from the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. But even in this town with its glorious past, traces of the persecution of Jews, of the horrors of the Holocaust and of the artistic handling of it can be found in any number of places. One last highlight was the meeting with the Auschwitz survivor Lidia Maksymowicz, who was one of the children abused by Josef Mengele under the pretext of medicine. With a gentle smile, Lidia Maksymowicz faced the tense – and reverent – group who met up with her in the Żydowskie Muzeum Galicja (Jewish Museum of Galicia). As she gave her account, you could tell that she is practised in telling her story. The story of a girl who, as far as historical studies show, survived Auschwitz the longest. A girl who, after the camp was liberated on 27 January 1945, grows up with a family in the town and only years later is reunited with her birth mother, who was living in the former Soviet Union. But contrary to our expectations, it wasn’t these parts of the story, in which Lidia Maksymowicz told about Mengele or horror figures such as Amon Göth[12], that were emotionally moving; instead it was the everyday moments that we take for granted, such as how it was to wake up for the first time in years alone in a warm bed. And it was statements such as this, that brought tears to the eyes of the people in the room.

Witnesses of the time are living testimony to past events. But they are also gradually disappearing. What remains?

The real question is: How can we take action to stop us forgetting? The educational trip organised by IBB and Porta Polonica showed one thing at least: Discussing and contemplating art is perhaps a good start in providing answers to this burning question.

Andrea Lorenz, January 2020

[12] Amon Leopold Göth (1908-1946) was an SS Commander in the forced labour camp of Kraków-Płaszów. For more on Göth and the forced labour camp, see Wolfgang Curilla: Der Judenmord in Polen und die deutsche Ordnungspolizei 1939-1945, Paderborn 2011, p. 379f.

Related links:

Centrum Żydowskie w Oświęcimu: https://artsandculture.google.com/partner/the-auschwitz-jewish-center

IBB: https://ibb-d.de/

Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum: http://auschwitz.org/en/

Marian Kołodziej Online Exhibition: http://harmeze.franciszkanie.pl/ausstellung-von-marian-kolodziej/

Literature

Barski, Jacek: ‘Birkenau’ by Gerhard Richter, Link: https://www.porta-polonica.de/en/atlas-of-remembrance-places/birkenau-gerhard-richter, last accessed on 19/12/2019.

Curilla, Wolfgang: Der Judenmord in Polen und die deutsche Ordnungspolizei 1939-1945, Paderborn 2011.

Gutman, Israel; Berenbaum, Michael: Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp, Washington D.C 1994.

Menges, Franz: Art. Mengele, Josef, in: NDB 17 (1994), p. 69-71.

Mielnikiewicz, Olga: Oświęcim. Historia społeczności, Link: https://sztetl.org.pl/pl/miejscowosci/o/546-oswiecim/99-historia-spolecznosci/137813-historia-spolecznosci, last accessed on 7/1/2020.

Mokrzycka-Pokora, Monika: Marian Kołodziej, in: culture.pl, Link: https://culture.pl/pl/tworca/marian-kolodziej, last accessed on 7/1/2020.

Online Services of the German Federal Parliament: Gerhard Richter presents the painting series “Birkenau” to the German Federal Parliament, URL: https://www.bundestag.de/dokumente/textarchiv/2017/kw36-richter-birkenau-525720, last accessed on 17/10/2019.

Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum: Wystawa sztuki w byłej kuchni obozowej, Link: http://auschwitz.org/muzeum/zbiory-historyczne/wystawa-sztuki-w-bylej-kuchni-obozowej/, last accessed on 7/1/2020.