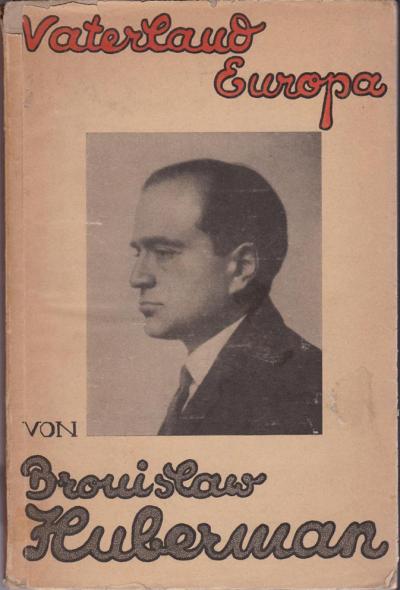

Bronisław Huberman: From child prodigy to resistance fighter against National Socialism

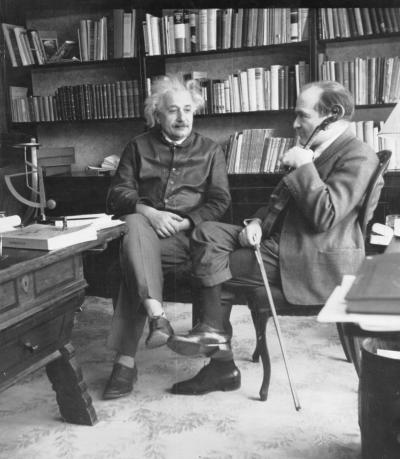

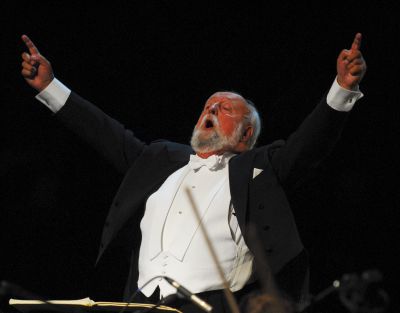

In May 1933, the Berliner Philharmonic Orchestra travelled to concerts in Geneva, Zurich and Basel and undertook a smaller tour through German towns to Vienna where the German Brahms Society and the Vienna Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde were putting on the Eighth Johannes Brahms Festival to mark the occasion of the composer’s birthday. Furtwängler directed the double concerto for violins and cello with Huberman and Pablo Casals as soloists. Whilst Schnabel performed as soloist in the second piano concerto, Huberman, Hindemith and Schnabel created the chamber music section. Because Furtwängler had to prepare his programmes for the forthcoming Berlin concert season in winter 1933/34, he intended to approach the Hitler government and ask for a special permit to allow some of the international music greats to perform. To do this, he called upon Huberman to commit and to actively participate. In a letter, Huberman reported: “During the Brahms Festival in Vienna, Furtwängler spent hours trying to convince me to give my consent to appear in case he could get the declaration of new directives that he had in mind from the government. I rejected this unreasonable demand as being beneath my dignity […].”[30] At this point, Huberman also provided a public statement.

Whilst Furtwängler had already spoken out in an open letter to Goebbels about outstanding artists remaining in German culture, such as “Walter, Klemperer, Reinhard[t] etc.,[31] a letter that Huberman knew very well, Furtwängler then presented his view once again “of a moderate entity close to the Reich Chancellery […] and his proposals were approved.”[32] On the strength of this, Furtwängler addressed personal invitations in June to Casals, Cortot, the Polish pianist Józef Hofmann, Huberman, Kreisler, Menuhin, Schnabel, the cellist Gregor Piatigorsky and the violin virtuoso Jacques Thibaud, however, they all declined. As Geissmar recalled, the soloists “in their response unanimously held the view that, despite Furtwängler’s personal efforts, the German music scene had been politicised – and all of them, Aryans and non-Aryans alike, refused to avail themselves of privileges that were only being granted to them because of their international reputation. They declared categorically that they would not perform in Germany until the same rights applied to all.”[33]

[30] Letter from Huberman to “Bn.” dated 18 October 1933, Huberman Estate (see Note 1), cited from von der Lühe 2004 (see Literature), page 71

[31] Goebbels über die Kunst. Correspondence with Furtwängler, in: Vossische Zeitung, No. 171, dated 11 April 1933, morning edition, page 3, online resource: http://zefys.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/index.php?id=dfg-viewer&set%5Bimage%5D=3&set%5Bzoom%5D=min&set%5Bdebug%5D=0&set%5Bdouble%5D=0&set%5Bmets%5D=http%3A%2F%2Fcontent.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de%2Fzefys%2FSNP27112366-19330411-0-0-0-0.xml

[32] Geissmar 1985 (see Literature), page 85. – This “entity” was obviously the Prussian minister of cultural affairs Bernhard Rust, member of the NSDAP, the Prussian State Parliament and the Reichstag, who headed up the Reich Ministry for Science, Education and Public Education from 1934 to 1945. Rust had convened a commission to regulate the future of the German music industry, a commission which comprised Furtwängler, Max von Schilling, Wilhelm Backhaus and Georg Kulenkampff and which, in the future, was to review “the programmes of all the public concert associations”. An exposé published on this subject stated, “that German artists, who are called upon to support and maintain a German music industry, have to be used first and foremost. It must, however, be pointed out that in music, as in any art form, the performance must always remain the crucial factor, with other considerations having to take a step back in favour of the principle of performance, if necessary.” (Prager Tagblatt dated 13 September 1938, Fig. 8). Furtwängler evidently considered the last sentence to be a guarantee that would also allow him to engage prominent foreign (or non-Aryan) artists in accordance with the principle of performance.

[33] Ibid