Bronisław Huberman: From child prodigy to resistance fighter against National Socialism

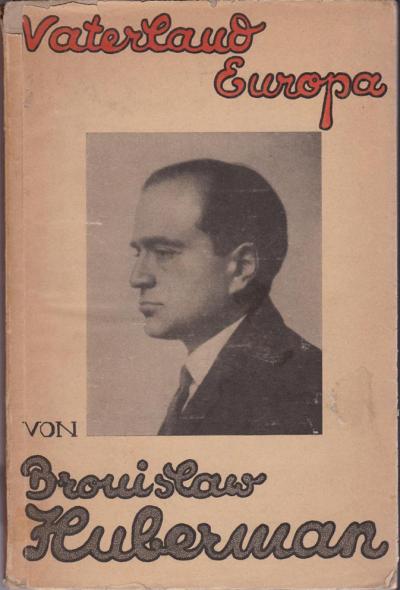

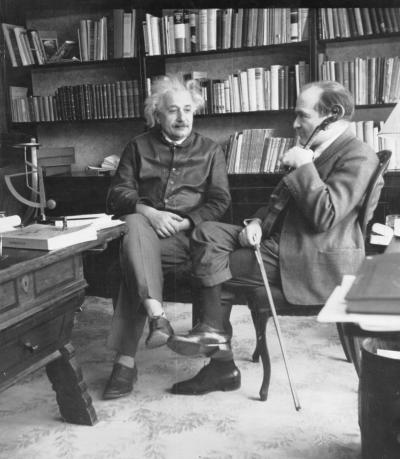

In 1926, wealthy benefactors provided Huberman with an apartment in Vienna in the state-administered Schloss Hetzendorf, where he then settled for the next decade. At this time, Huberman was already known as “one of the most interesting and intellectual minds of our time”, as the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung reported on 2 February 1926: “Thanks to the authority bestowed upon him by his notability, the artist has done an incredible amount for the Pan-Europe movement in particular, and what’s more, he has used his truly creative ideas to point this young movement in new directions.[17] Huberman was one of the main speakers at the first Pan-Europe Congress, which was held in the great hall of the Konzerthaus in Vienna in October 1926, had two thousand participants and played out in front of six hundred representatives from national and international media. In his speech, which was again printed in his second paper “Vaterland Europa” (Fig. 7) published in Berlin in 1932, he set out the integration goals and processes necessary for European unification, such as customs and monetary union, legislative alignment, setting up a supranational army, protection of minorities and the invisibility of borders. Whilst the German envoy in Vienna, Count Hugo Lerchenfeld (1871-1944), made disparaging comments in his report to the Foreign Minister in Berlin, Hugo Stresemann (1878-1929), the Frankfurter Zeitung wrote: “ […] we were surprised to hear him talking instead of playing the violin. But that is what made you take it seriously – that a great artist […] feels the urge to get involved with politics. […] Old Europe must be in great distress if she does not even leave the musicians in peace.”[18] The congress ended with a violin solo from Huberman.[19]

Meanwhile, Huberman’s international concert activities had helped him to achieve great wealth and this allowed him to support young musicians and to donate takings from his concerts as well as his own money to charitable causes. He donated funds to the Vienna National Library and in 1928 to the public purchase of an estate in Żelazowa Wola to the west of Warsaw where Chopin’s birthplace was to be found and for which money had been collected throughout Poland. He supported contemporary composers by performing their works. With Poland being represented at the first Pan-Europe Congress by Władysław Landau, a socialist and delegate of the League of Nations leagues and a leader of the Polish students,[20] Huberman initiated and supported the founding of a national Pan-Europe committee in Poland. This was joined by intellectuals, left-wing activists and young academics, including pacifists and friends of the League of Nations.[21]

[17] Newspaper article in the Huberman Estate (see Note 1), cited from Platzer 2019 (see Literature), page 61 f.

[18] Frankfurter Zeitung dated 9 October 1926, Huberman Estate (see Note 1), cited from Platzer 2019 (see Literature), page 125

[19] Neue Freie Presse, Vienna, No. 22294, dated 7 October 1926, morning paper, page 3, online resource: http://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=nfp&datum=19261007&seite=3&zoom=33&query=%22Huberman%22&ref=anno-search

[20] Landau spoke out in favour of the German-Polish friendship: “The youth of Germany and Poland must find itself; it is a disgrace of the twentieth century that we Poles and Germans do not have the closest of relationships, that we still have to fight a customs war and that we are still fighting an internal war in our hearts. I beg of you not to believe the rumours that Poland wants war.” (Neue Freie Presse dated 7 October 1926, ibid). Compare also Dagmara Jajeśniak-Quast: Polish Economic Circles and the Question of the Common European Market After World War I = Individual publications of the Deutsche Historische Institut Warsaw, Volume 23, Warsaw 2010, page 136, digital version: https://perspectivia.net/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/ploneimport_derivate_00011467/jajesniak-quast_circles.pdf

[21] Platzer 2019 (see Literature), page 127