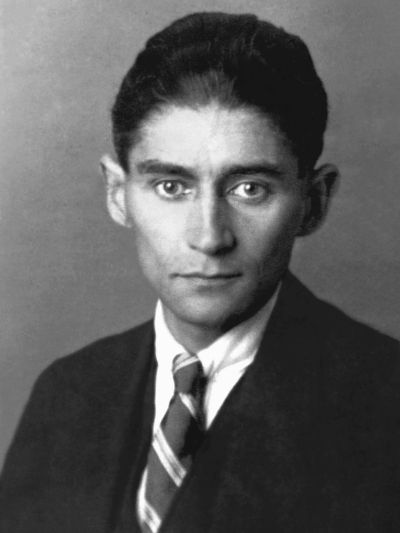

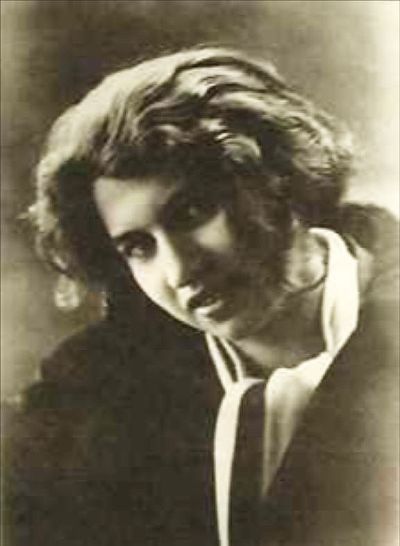

Dora Diamant – activist, actress, and Franz Kafka’s last companion

For many years, little pieces of information from very specific periods in time were known about Dora Diamant. The writer Max Brod (1884–1968), Franz Kafka's close friend who later became the executor of his literary estate, knew of her existence no later than September 1923, when Kafka mentioned her in postcards and letters sent to Prague from the Steglitz district in Berlin. On 9 November, Brod travelled to Berlin to visit his lover, the actress Emmy Salveter, check up on Kafka’s state of health, and meet Kafka’s new girlfriend, Dora. From that time on, Dora always sent greetings to Brod. In a letter dated January 1924, she stressed that “I’d also like to write to Max”.[1] Kafka’s youngest sister, Ottla (1892–1943, Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp) and her husband, Josef David (1891–1962) knew about Dora by December 1923 at the latest, while Kafka’s parents regularly received news about her from January 1924, and also received notes and greetings from her in person. In his last letter to his parents, Kafka, whose tuberculosis had spread to his larynx in the spring of 1924, wrote on the day before he died of the “help given by Dora, which from a distance is wholly unfathomable”.[2] Dora Diamant was also regularly mentioned in Kafka’s letters to the young Tile Rössler (Tehila Ressler, 1907–1959), who lived with her parents in Berlin and who would later become a dancer, to his previous lover Milena Jesenská (1896–1944, Ravensbrück concentration camp), to the elocutionist and reciter Ludwig Hardt (1886–1947), and to his friend Robert Klopstock (1899–1972), who together with Dora cared for Kafka until his death.

Dora Diamant recounts her life with Franz Kafka

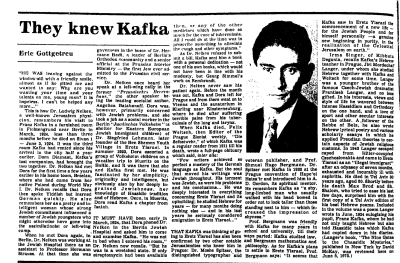

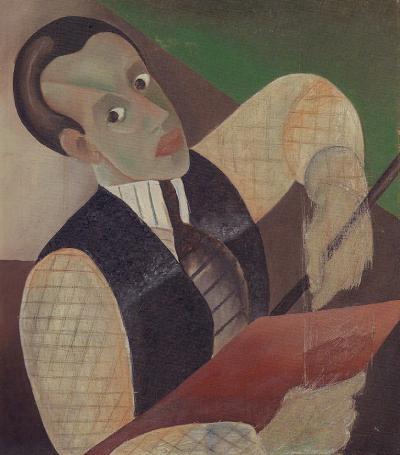

Diamant publicly spoke about her life with Kafka for the first time just over two years after the end of the Second World War. In London, Dora Dymant, as she called herself after her move to England, and the painter Friedrich Feigl (1884–1965), a fellow pupil of Kafka’s in Prague, were interviewed by the author and art historian Josef Paul Hodin (1905–1995). Originally from Prague, Hodin was a graduate of law, biographer of the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch, and press attaché of the Czechoslovak government in exile in London. Feigl, who had lived with his wife in Berlin since 1910, had met Kafka there again, together with Dora Diamant. Hodin turned the two interviews into a long essay, “Memories of Franz Kafka”, which appeared in the monthly London literary journal “Horizon – A Review of Literature and Art” in January 1948. In June 1949, a German version was published in Berlin in the US military government magazine “Der Monat”, an “international journal for politics and intellectual life”.[3]

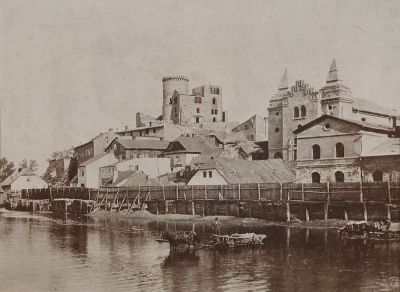

Feigl, who had attended the German-language grammar school, the Deutsches Altstädter Gymnasium in Prague together with Kafka, and who had subsequently studied at the Prague Academy of Fine Art, told Hodin that Kafka had introduced him to his fiancée, Dora Diamant, in Berlin and that he had purchased one of his pictures, a somewhat sinister study of Prague, which Kafka had given to Diamant as a gift.[4] Hodin wrote that he had spent many hours with Ms Dora Dymant, during which time they had talked about Kafka and the final months of his life. She had conceded that it was not possible to be objective more than 20 years following Kafka’s passing. “But after all, one can only measure time by the importance of one’s experiences. Even today it is often difficult for me to talk about Kafka. Frequently it is not the facts which are decisive, it is a mere matter of atmosphere. What I tell has an inner truth. Subjectivity is part of it.”[5]

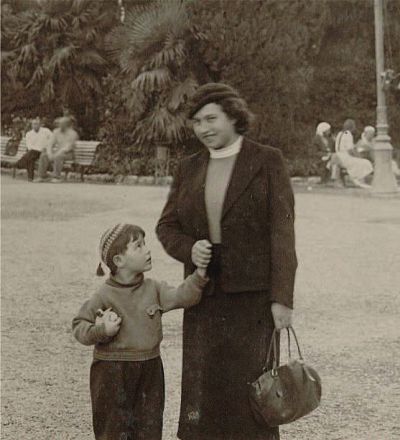

In the interview, Diamant spoke of the first time she met Kafka, whom she first noticed on the beach in Müritz in the company of his sister Elli (1889–1942, Kulmhof death camp) and her two children, Gerti and Felix. Kafka’s presence made an impression on her, and she followed them into the town. That evening, she saw him again in the “Haus Huten”, the holiday home of the Jüdisches Volksheim, where Dr. Franz Kafka from Prague had been invited to dinner as the guest of honour. The large, two-storey lodging house on the edge of the birch forest to the east of Müritz[6] was situated within sight of the “Landhaus Glückauf”, where Kafka was living. She described his manner of behaviour and his character, their life together later on in Berlin, the idiosyncrasies of his writing process, his everyday habits and quirks, gave information about the writers and publicists who came to visit him, such as Franz Werfel (1890–1945), Willy Haas (1891–1973) and Rudolf Kayser (1889–1964)[7], as well as the literature he loved, including Kleist’s “Marquise von O.” and Goethe’s “Hermann und Dorothea”. She talked about his departure from Berlin to live with his parents in Prague for health reasons, his admission to sanatoriums in Lower Austria and Klosterneuburg, and about his death.

She gave only scant information about herself. She said that she had come “from the east”, “as a dark creature full of dreams and premonitions, as though sprung from a novel by Dostoevsky”. She had heard so much “about the west, about its knowledge, its clarity and its way of life”. After the end of the First World War, she travelled “to Germany with a receptive soul”. “After the catastrophe of the war, everyone expected salvation to come from the east. I, however, ran away from the east, because I believed that the light came from the west. [...] In the east, there was a knowledge about mankind; it may have been impossible to move so freely about in society, and to express oneself so easily, but there was an awareness of the unity between mankind and creation. When I saw Kafka for the first time, his appearance immediately fulfilled my mental image of mankind”.[8]

[1] Letter from Franz Kafka to Max Brod, Berlin-Steglitz, arrival postmark Praha-Hrad, 14/1/1924, in: Max Brod, Franz Kafka – eine Freundschaft. Volume 2: Briefwechsel, Frankfurt/Main 1989. Letters of Franz Kafka from various sources can be accessed on the website of ADir. Werner Haas (University of Vienna) via a search function: https://homepage.univie.ac.at/werner.haas/ (last accessed on 04.08.2023). – Max Brod, who had graduated as a lawyer and who was a respected novelist in his own right, worked as an official at the central post office in Prague until the spring of 1924, then as an art and literary critic at the “Prager Tagblatt” newspaper. Dora Diamant addressed postcards written by Kafka to Max Brod dated 20/4 and 28/4/1924 to the postal address of the “Prager Tagblatt”.

[2] Letter from Franz Kafka to his parents, Kierling, Dr. Hoffmann’s Sanatorium, 2/6/1924, in: Franz Kafka. Briefe an Ottla und die Familie, published by Hartmut Binder and Klaus Wagenbach, Frankfurt/Main 1975; also in: Brod 1962 (see Bibliography), page 257 f.

[3] Hans-Gerd Koch wrote a summary of the German translation of the interview from “Der Monat” under the author’s name Dora Diamant, entitled “Mein Leben mit Franz Kafka” (“My life with Franz Kafka”), and re-published the article in 1995 in his collected volume “Als Kafka mir entgegenkam ...” (see Bibliography), page 174–185. Klaus Wagenbach 1964 [10th edition 1972, see Bibliography], page 146, quotes another version under the name Dora Dymant, entitled “Ich habe Franz Kafka geliebt” (“I loved Franz Kafka”), from: “Die Neue Zeitung”, 18/8/1948. This newspaper was released in Munich from 1945 onwards, and later appeared with its own edition in Berlin as “an American newspaper for the German people”, published by the US Army; see Bernhard von Zech-Kleber: Die Neue Zeitung, at: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns, https://www.historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de/Lexikon/Die_Neue_Zeitung (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[4] Hodin 1948 (see Bibliography), page 32–34.

[5] Ibid., page 35.

[6] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 26.

[7] The literary historian Rudolf Kayser had been the editor of the Berlin literary journal “Die neue Rundschau” since 1922. The October edition of that year included Kafka’s novella A Hunger Artist (Ein Hungerkünstler). In the July volume of 1924, Kayser wrote an obituary of Franz Kafka (Volume 35, Vol. 2, book 7, page 752); re-printed in the collected volume of Hans-Gerd Koch: “Als Kafka mir entgegen kam …” 1995 (see Bibliography), page 196 f.

[8] Dora Diamant: Mein Leben mit Franz Kafka 1995 (see note 3), page 175.