Dora Diamant – activist, actress, and Franz Kafka’s last companion

The stage boards that mean the world

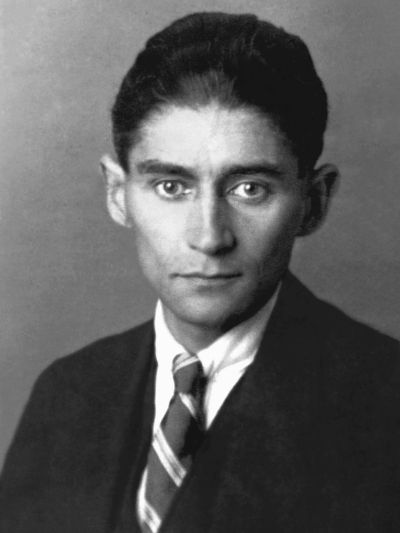

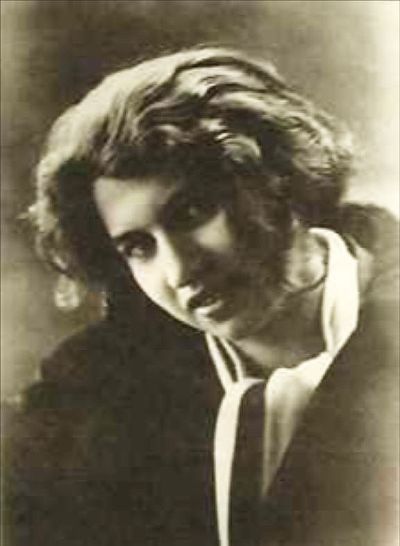

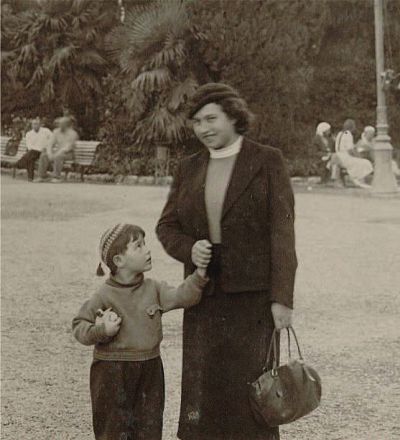

Two months later, in August 1924, Diamant (Fig. 9) suddenly packed her bags and left. Urzidil had organised a residence permit for her for Germany, with which she was able to travel to Berlin. Kafka’s family had given her a small amount of money to take with her. At first, the German capital, as she wrote to Elli, felt “like the cemetery of my life, where I came to visit the graves”. A few days later, friends found her a room in a student hostel. She had hopes that she would be able to begin training as an actress.[81] In October, she reported to Ottla in a letter that she was about to take the entrance exam to the state acting school. She wrote that she had been helped in preparing for the exam by an actress who was an acquaintance of the theatre director and manager, Max Reinhardt (1873–1943). By January 1925, she had found greater stability in her life. Although she had failed the entrance exam to the acting school, she had moved into a new apartment, had found work, attended courses and did gymnastics. She also developed a friendship with the Polish-Yiddish poet Avrom Nokhem Stencl (Sztencl, Stenzel, Abraham Nahum Stencl, Avrom-Nokhem Shtentsl, 1897–1983), who came from Czeladź, a neighbouring town to the west of Będzin.[82]

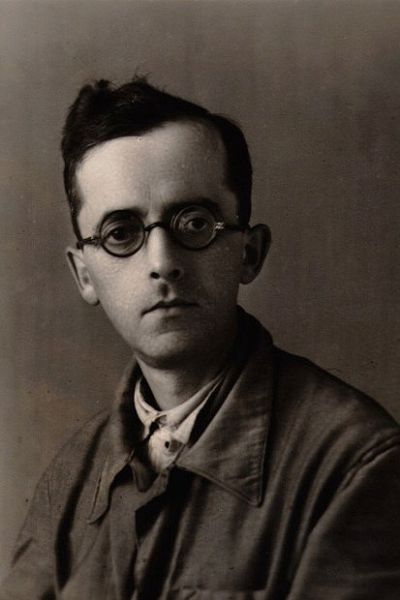

Stencl, who had fled conscription to the Polish army in 1918, had arrived in Berlin via the Netherlands in 1921, the same year as Diamant. He remained in Berlin until his emigration to Britain in 1936. During this time, he published ten volumes of Yiddish poetry. Often homeless, with his pockets full of poems, he gathered other Polish literati from his home region around him and sought contact with non-Jewish literary expressionists. From 1922 onwards, he collaborated with the poet Else Lasker-Schüler (1869–1945) and spent many sociable hours in the Romanisches Café on Kurfürstendamm, where Jewish exiles, intellectuals and activists from Poland, Ukraine and Russia mingled with artists, actors, journalists and chess players. It is likely that he fell in love with Diamant,[83] although he was in a committed relationship with the artist Elisabeth Wöhler, who worked at the Free Secular School (Freie Weltliche Schule) in Reinickendorf, where he also taught. In 1942, Diamant met him again in Whitechapel, London, where he established himself as the “Poet of Whitechapel”[84], declaring the area his British shtetl.[85] (Fig. 10) Like Diamant, he was committed to the dissemination of the Yiddish language, and published “Loshn un lebn” (“Language and Life”), for which Diamant wrote articles from 1945 to 1949.

In the spring of 1925, Diamant (Fig. 11) fell seriously ill. When she ran out of money, she went to stay with relatives in Brzeziny, the birthplace of her mother. At the beginning of 1926, she returned to Berlin and moved into a room at the orphanage in Charlottenburg. During that year, Brod published Kafka’s novel “The Castle” (Das Schloss) via the Kurt Wolff Verlag publishing house in Munich. From that time on, Diamant, to whom he sent a free copy, started collecting any writings and novels that were published, and anything else that was written about Kafka. She found new lodgings in an artist’s studio in the Hansaviertel district, not far from the Tiergarten, earned money from sewing, and took up acting classes again. Klopstock, who was now living in Kiel, visited her in Berlin during the Whitsun holiday. Brod and Haas, who had edited the journal “Die literarische Welt” in Berlin since 1925, paid her royalties received from Kafka’s novels and stories. It was thanks to these that Diamant, whose health had still not fully recovered, was able to afford a two-month holiday on the Baltic coast.[86]

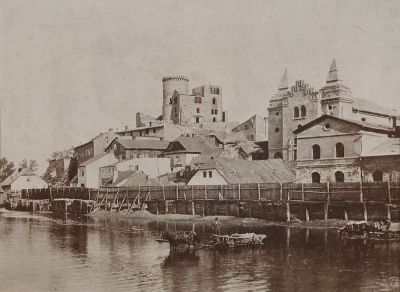

In November 1926, after applying for acting training courses and theatre roles across Germany, she was accepted at the Academy for Dramatic Art (Hochschule für Bühnenkunst), which was affiliated with the Schauspielhaus Düsseldorf theatre (Fig. 12). The course curriculum comprised of reading plays, elocution, role study, theatre history, fencing and gymnastics. During the evening, the students took part in rehearsals in the Schauspielhaus and played minor roles in the performances. The most famous student at the academy was the actor Gustav Gründgens (1899–1963), who had studied there in 1919/20. The Schauspielhaus was run by the actress Louise Dumont (1862–1932) and her husband Gustav Lindemann (1872–1960), who had founded it as a private theatre in 1904. Their main focus was ensemble work, and they made the theatre famous as a “reform stage”. A qualification from the academy which they also founded was considered a guarantee of success for a future career. From November 1926 to May 1928, Diamant (Fig. 13) attended classes given by Dumont, who was well known throughout Europe for her performance of Hedda Gabler and other Henrik Ibsen characters, as well as by the actor and director Hermann Greid (1893–1975) and the actor and later theatre manager, Franz Everth (1880–1965).[87]

In early 1927, it is likely that Brod met Diamant when he came to Düsseldorf for the première of his play “The Opuntia – Comedy of a Prominent Individual” (Die Opuntie – Komödie eines Prominenten, 1926) in the small house (Kleines Haus) of the rival Düsseldorf Stadttheater, where he held a series of lectures from February to March. During that same year, he published Kafka’s third novel, “Amerika”, and was again able to negotiate royalties for Diamant.

We can assume that it was in Düsseldorf in 1927 that Diamant also met the poet, playwright and journalist Berta Lask (1878–1976), her future mother-in-law, for the first time. Lask, who was born in Wadowitz/Wadowice in Galicia, had become radicalised following her experiences of the First World War in which she lost both her brothers, the Russian October Revolution, the November Revolution of 1918 in Germany, and not least the poverty in Berlin during the post-war years. After early literary attempts, she published poems, stories and plays which were closely linked to the Expressionism and literary activism surrounding Kurt Hiller (1885–1972). In 1923, she joined the KPD, the Communist Party of Germany. In 1927, she was due to produce her play “Leuna 21”, about the workers’ revolt during the “March Action” of 1921, at the Düsseldorf Schauspielhaus theatre. Shortly before, the premiere of the play had been banned in Berlin, and its first night in Düsseldorf was also prohibited by the authorities. Lask was accused of high treason, and her works were removed from the bookshops.

At this time, Diamant, as she would later recount for the record in Moscow, was also in contact with a “Sternberg Group”. This was a political group oriented around the theories of the sociologist and Marxist theoretician Fritz Sternberg (1895–1963), who had been influenced by the theories of Martin Buber, a Jew from Breslau. It was through this group that Diamant “was introduced to the basics of Marxism”. She was “enlightened” about communism by the actor Wolfgang Langhoff (1901–1966), a fellow actor at the Schauspielhaus and a communist, KPD member and later member of the Association of Revolutionary Fine Artists (Assoziation revolutionärer bildender Künstler) or ASSO.[88]

From October 1927 onwards, Diamant acted at the Schauspielhaus in performances of “The Prince of Homburg” (Der Prinz von Homburg) and “The Broken Jug” (Der zerbrochene Krug) by Heinrich von Kleist, and from January 1928 she played a “Moorish girl” in Henry Ibsen’s play “Peer Gynt”. Diamant’s teachers, Greid and Everth, praised her “strong, unique talent”.[89] While on arrival in Düsseldorf she had officially registered as “Dwora Dimant”, in January 1928, she altered the spelling of her surname to “Dymant”. However, a fellow actress, Luise Rainer (1910-2014), who would quickly become famous, knew her simply as “Doris”: “She was a dark person, always dressed in black, as though she was in mourning. I had never read Kafka, but she talked to me constantly about him. [...] She seemed to me to be entirely suffused by him. [...] Doris was a real character. She was someone”.[90] As Diamant recounted to Brod, she completed her training in May 1928 with a lecture evening at which she read from Kafka’s novel “Amerika”. She again applied for work at numerous German theatres – among them theatres in Berlin and the Hamburgische Schauspielbühne theatre run by Madeleine Lüders (1892–1966). This time, she was able to show letters of recommendation from the academy.[91]

She then received a booking for the coming autumn season, in the neighbouring town of Neuss, at the Rhine Town Alliance Theatre (Rheinisches Städtebundtheater), founded in 1925, later the Rhine Federal State Theatre (Rheinisches Landestheater), whose mission it was to provide an education to ordinary people, and which had close links to the Theatre People’s Federation (Bühnenvolksbund) and the People’s Theatre Associations (Volksbühnenvereine). As a travelling drama theatre, it not only gave performances in its main house. During the 1928/29 season, it travelled to 42 towns and communities in the local region, with Diamant taking part. Together with a colleague, she shared the main role of Princess Alma in Frank Wedekind’s allegorical drama King Nicolo, or Such is Life (König Nicolo oder So ist das Leben), in which she performed in the Gladbeck town theatre and elsewhere. At the end of October, she played the maid Sophie in Friedrich Schiller’s Intrigue and Love (Kabale und Liebe) in front of a full house in Neuss. In November, she appeared in two one-act plays on the same evening: in Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s The Fool and Death (Der Tor und der Tod), she played a dead lover of the nobleman Claudio, and in the contemporary play A Game of Death and Love (1925) by the winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, Romain Rolland, she played the role of Chloris Soucy. The “Düsseldorfer Nachrichten” newspaper reported on a “stirring performance”, into which Dora Dymant “fitted excellently”.[92] In the comedy “The Lucky Candidate” (Der Glückskandidat) by the Düsseldorf playwright Hans Müller-Schlösser, it is likely that she took on a minor role, as was the case with other productions during that season.[93]

[81] Dora Diamant to Elli Hermann (née Kafka) from August/September 1924, Bodleian Libraries; quoted from Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 175. – The Archive of Franz Kafka of the Bodleian Libraries at the University of Oxford houses the largest collection of notebooks and letters belonging to Franz Kafka, as well as correspondence of the Kafka family. Digital finding aid at: https://archives.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/repositories/2/resources/12214 (last accessed on 4/8/2023), including letters from Dora Diamant.

[82] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 167–184.

[83] Ibid., page 183, 233.

[84] Gennady Estraikh: Introduction. Yiddish on the Spree, in: Yiddish in Weimar Berlin. At the Crossroads of Diaspora Politics and Culture, edited by Gennady Estraikh and Mikhail Krutikov (Studies in Yiddish, 8), London/New York 2010, page 22.

[85] Heather Valencia: Czeladz, Berlin and Whitechapel. The World of Avrom Nokhem Stencl, in: European Judaism. A Journal for the New Europe, Volume 30, No. 1, Spring 1997, page 4–13; see also Heather Valencia: A Yiddish Poet Engages with German Society. A. N. Stencl’s Weimar Period, in: Yiddish in Weimar Berlin 2010 (see note 84), page 54–72.

[86] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 185–196.

[87] Schaller 2017 (see Bibliography), page 269.

[88] Dora’s account of her life in the Komintern file in the Russian archives, quoted from Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 241.

[89] Letters in the Dumont-Lindemann-Archiv of the Theatermuseum Düsseldorf.

[90] Interview by Kathi Diamant with Luise Rainer-Knittel, 2002; quoted from Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 203.

[91] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 197–206.

[92] “Düsseldorfer Nachrichten”, 4/11/1928; quoted from Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 206.

[93] Schaller 2017 (see Bibliography), page 270–279.