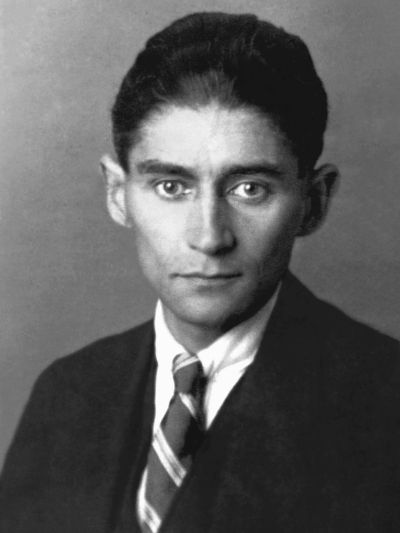

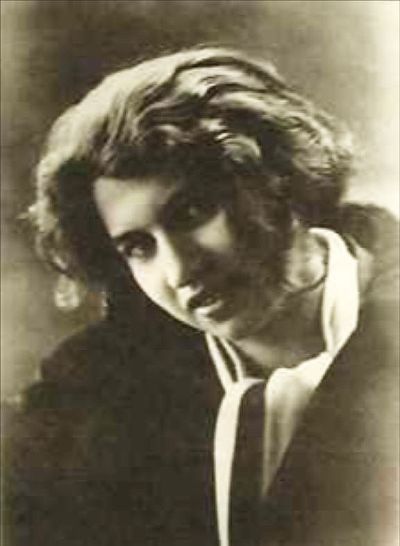

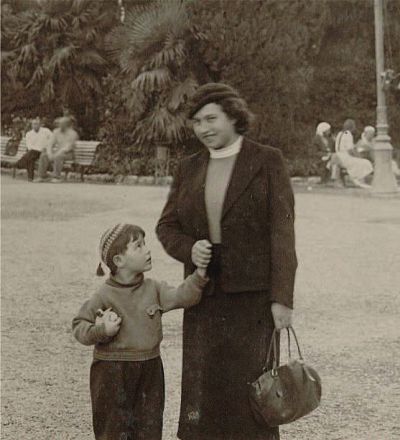

Dora Diamant – activist, actress, and Franz Kafka’s last companion

Finally, researchers are taking an interest in the topic

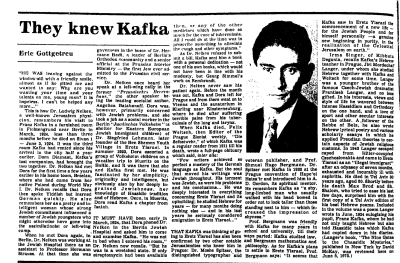

In the two decades that followed the publication of the Frankfurt edition of Brod’s Kafka biography, no-one appeared to be interested in filling in the missing years in Dora Diamant’s life. It was thought that the period before her first meeting with Kafka in Müritz and the 28 years after his death had nothing to contribute to the ever-increasing amount of literature about the writer.[23] Finally, in 1984, the German-American translator and biographer Ernst Pawel (1920–1994), who was born in Breslau/Wrocław, added details of Diamant’s life after the late 1920s in his award-winning Kafka biography “The Nightmare of Reason”. He wrote that during this time, she married a prominent leading member of the German Communist Party (Deutsche Kommunistische Partei) and had a child with him. In February 1933, several days after the National Socialists seized power, her husband fled abroad. He managed to escape just in time before a manhunt was conducted by the Gestapo and their shared apartment was searched. During the search, papers originally belonging to Kafka were confiscated. Pawel continued that a short time later, Diamant left Germany with her child and moved to Moscow. Her husband was arrested in the Soviet Union, Pawel wrote, then convicted as a Trotskyist saboteur and deported to Vorkuta. She never heard from him again. After her daughter fell ill with a kidney disease, Pawel wrote that Diamant was granted permission to leave for England in 1938, where Diamant’s daughter remained after Diamant’s death in 1952.[24]

Pawel also quoted from a letter from Diamant to Brod in May 1930 from Berlin-Charlottenburg, which Brod had already published in 1966 without further comment, and in which she described her ambivalent relationship to Kafka’s literary work and the planned publication of his estate: “As long as I was living with Franz, all I could see was him and me. Anything other than him was simply irrelevant and sometimes ridiculous. His work was unimportant at best. Any attempt to represent his work as part of him seemed to me simply ridiculous. That is why I objected to the posthumous publication of his writings. And besides, as I am only now beginning to understand, there was the fear of having to share him with others. Every public statement, every conversation, I regarded as a violent intrusion into my private realm. [...]”[25]

At this time, in May 1930, Diamant had still kept hidden the fact that after Kafka’s death, she had withheld a significant number of his manuscripts and letters, which ultimately led to their being lost when they were seized by the Gestapo. Here, too, Brod had already stated earlier that Diamant had been forced to admit in the end that this was the case. Following the seizure of a portion of Kafka’s estate “from Mrs Dora Dymant”, he, Brod, asked Camill Hoffmann (1878–1944, Auschwitz concentration camp), the press attaché of the Czechoslovakian Embassy in Berlin, to “look into the matter and to intervene”: “This time, his efforts were in vain. Soon, he himself vanished into the storm of the times [...] Auschwitz? We can assume that Kafka’s Berlin estate is lost”.[26]

In the mid-1980s, the theatre scholar Kathi Diamant (*1952), who now lives in San Diego, California, began intensive research into Dora Diamant’s life. She had already discovered the existence of the woman who shared her name while studying German literature in 1971. After reading Pawel’s biography of Kafka, she travelled to Poland, Germany, France, Britain, Czechoslovakia, and Israel to conduct research. Her work took her to public libraries such as the Pabianice City Museum (Muzeum Miasta Pabianic) and the local registration office (Urząd stanu cywilnego), where she found Dora’s birth certificate, to the Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History in Moscow, where Dora Diamant’s Komintern file is held, the Archives of the Political Parties and Mass Organisations of the GDR Foundation (Stiftung Archiv der Parteien und Massenorganisationen der DDR), to the Federal Archive (Bundesarchiv) in Berlin and the Berlin State Archive (Landesarchiv), which contains Gestapo files on Dora and the Lask family, and to the Düsseldorf City Archive (Stadtarchiv Düsseldorf), where the registration document and residence permit of Dora Diamant are stored. In private collections, she found letters from 1941 and 1951/52, among other items, and in the estate of Marthe Robert in France, the “diary” that was intended as the basis for Diamant’s “memories” of Kafka, which were never published. In the Archiv Klaus Wagenbach, she found a duplicate copy of the “diary”, together with texts, notes and letters from the time of Dora Diamant’s illness and death.[27]

In 2003, Kathi Diamant published the biography, which was around 400 pages long, in New York. In “Kafka’s Last Love. The Mystery of Dora Diamant”, she made the “diary” and other chronological notes available to the public for the first time. Her book was translated into Spanish, French, Chinese, Russian, and Portuguese. The German version did not appear until a decade later. It contains a transcription of Dora Diamant’s notes from the original German documents, with the addition of facsimile photographs.[28] Not included are 70 letters from Dora Diamant to Max Brod, which were not accessible due to a legal dispute surrounding Brod’s estate in storage in Israel that ran from 2005 onwards. In 2016, the estate was awarded to the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem and has been available for access since 2019.[29]

[23] The literary scholar and Kafka biographer Reiner Stach (*1951) points out that wives of famous men were traditionally assigned the “honorary task” of “kindling the male spirit and providing sensual fuel”: “‘The genius and his muse’ is a topos of more recent European cultural history, and in terms of ideology is one of the most persistent: even in the 20th century, when the concept of genius has already long been rendered obsolete”. The same, he writes, is true of “Felice, Milena, Dora”, “women, therefore, with whom Kafka had an important erotic relationship, and who we know influenced his literary work”. While a huge bundle of letters has been preserved from Felice Bauer, Kafka’s first fiancée, his “Letters to Milena”, to Milena Jesenská, which were published in 1952 by Willy Haas, sound almost like the title of a work of literature. As a result, these women are regarded as “mere projection surfaces”. “As regards Dora Diamant, no-one had any idea who she was, except that she must have been an extraordinary piece of luck for the severely ill Kafka. It was not until the end of the last century that palpable frustration arose among researchers and the general public alike that we were still being presented with faceless muses. Now, there is an increased awareness of the fact that this could in no way have been what Kafka would have wanted. After all, the people to whom he was close, whom he had in a certain sense chosen, certainly were of importance to his life – never mind the fact that these women also became interesting in their own right”. (Foreword by Reiner Stach, in: Kathi Diamant 2013, German language edition (translated from the German) (see Bibliography), page 17 f.

[24] Pawel 1984 (see Bibliography), page 438 f.

[25] In Pawel 1984 (see Bibliography, page 438) English-language publication. Quoted in the German original from Max Brod: Der Prager Kreis, Stuttgart et al.: Kohlhammer, 1966, page 113.

[26] Max Brod: Streitbares Leben 1884–1968, Munich et al.: F. A. Herbig, 1969, page 14 f.

[27] Foreword to the first German language edition (translated from the German), in: Kathi Diamant 2013, see Bibliography, page 13 f.; sources, ibid., page 441–443.

[28] Foreword to the German language edition (translated from the German), in: Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 15 f.

[29] Tim Aßmann: Max-Brod-Nachlass in Israel. Kafkas Vokabelheft, on: Deutschlandfunk radio, 7/8/2019, https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/max-brod-nachlass-in-israel-kafkas-vokabelheft-100.html (last accessed on 4/8/2023).