Stanisław Toegel

Mediathek Sorted

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

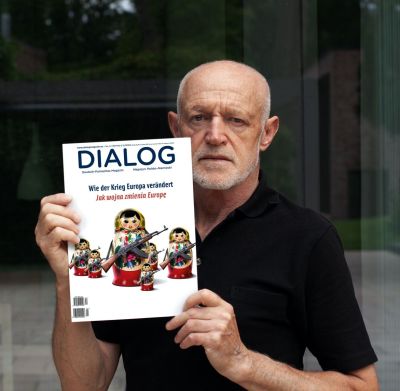

Stanisław Toegel - Hörspiel von "COSMO Radio po polsku" auf Deutsch

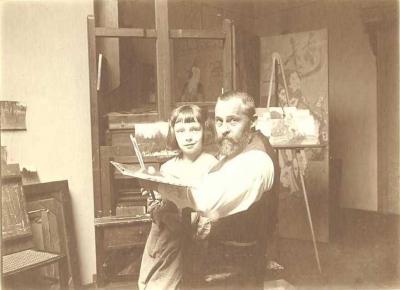

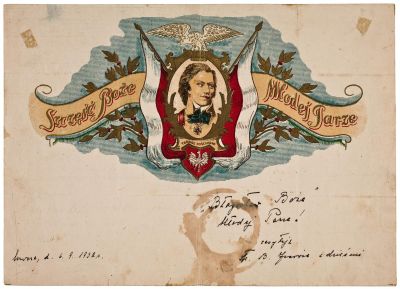

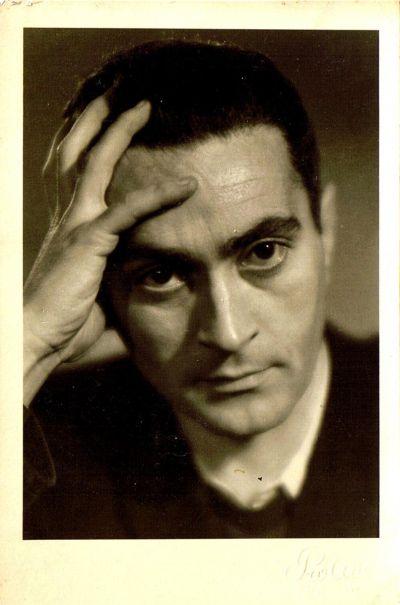

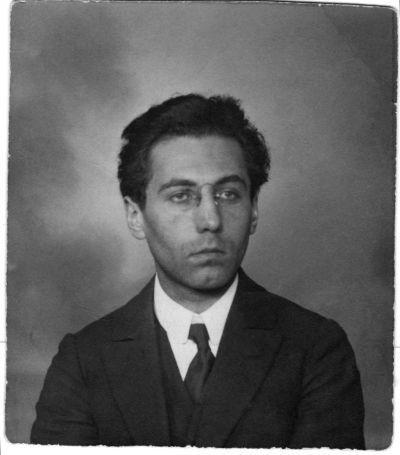

Stanisław Toegel was born on 20th August 1905 in Jaworów (today Jaworiw), 50 kilometres west of the regional capital, Lemberg. He studied law at the University of Lemberg and during this time he also made a name for himself as a caricaturist. Bogusław Bakuła, a literary scholar at the Institute for Polish Philology at the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, reports that Toegel was an habitual visitor to the Lemberg bar Pod Gwiazdką (Engl. The Star), a regular meeting place for “leftish” Polish, Ukrainian and Jewish young people ”who were at more or less peaceful odds with the artistic authorities in Lemberg … Polish intellectuals like Karol Kuryluk and Stanisław Piętak from the circle around the Lemberg newspaper Sygnały, and Ukrainian literati with left-wing orientations like Jaroslav Halan and Stepan Tudor also frequented the bar. But there were also signs that the bar was a meeting place for activists from the banned Communist Party of West Ukraine and even perhaps for members of combat units.” According to Bakuła, Toegel drew some “wonderful caricatures of visitors to the bar that was always packed out because the owner was willing to put drinks on the slate.”

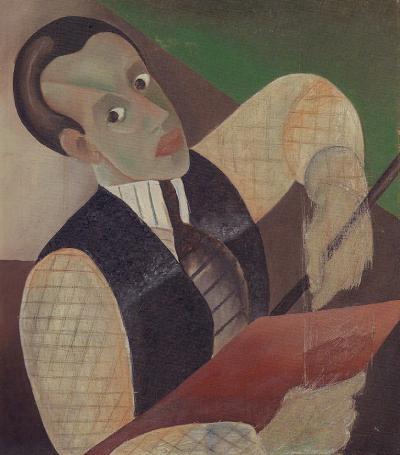

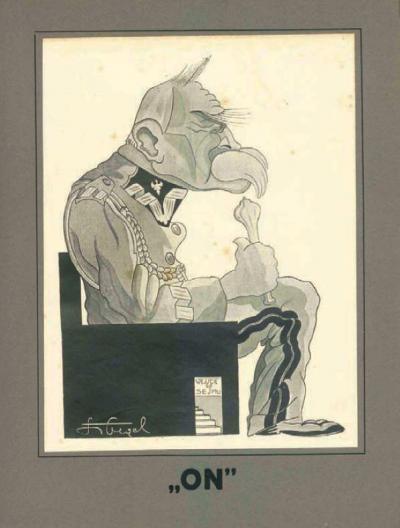

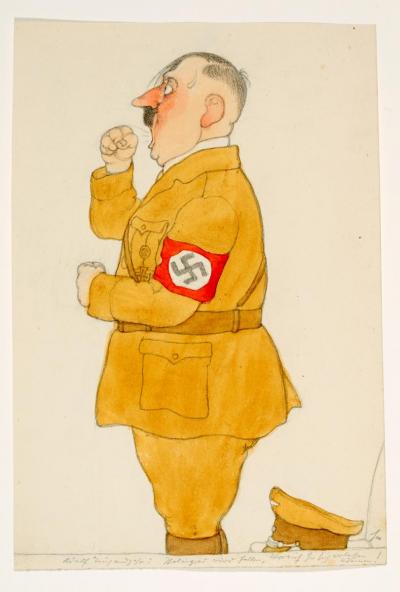

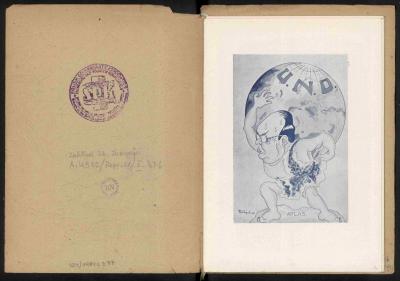

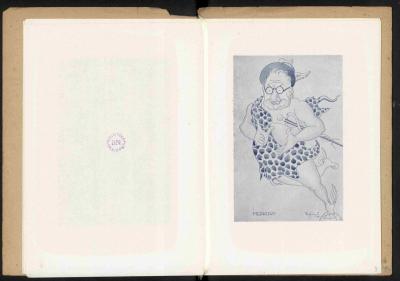

Toegel was a talented self-taught artist. That said, drawing caricatures was not uncommon amongst the bohemian circles of painters and writers. The walls in the Atlas restaurant where the Lemberg painters met up, and from which the “lefties” moved on to the Star, were full to bursting with caricatures and poems executed by the regular guests. During his time as a student in the mid 20s, Toegel wrote articles for the Lemberg newspapers Dziennik Polski and Kurjer Lwowski, which also published his first satirical drawings. In 1932 he published a folder with 16 printed caricatures in grey tones in an impressive 42 centimetre high format. They portrayed all the important politicians in the Second Polish Republic, including Ignacy Jan Paderewski, August Zaleski, Wincenty Witos and Roman Dmowski, as well as the two Generals Władysław Sikorski and Bolesław Wieniawa-Długoszewski. Beneath his caricature of Marshal Józef Piłsudski he wrote the word “ON” (Engl. “HIM”). Piłsudski had reigned in the background since 1926 and Toegel showed him sleeping with his marshal’s baton in his right hand on a black throne beneath which there is a tiny entrance to the Sejm, the Polish parliament (ill. 1).

Sometime during the 1930s Toegel moved to Warsaw with his wife Olga, to work for an insurance company. From the sparse information about his life, we know that he was a reserve officer in the September Campaign in 1939 when the Polish army fought to prevent the entry of the German forces into Poland. He was thrown into prison but managed to escape and went underground in Warsaw. Here he was active as a soldier in the Home Army (Armia Krajowa) where he allegedly took part in sabotage actions. In 1943 and 44 he drew biting caricatures of the Nazis for the underground press. In August 1944 he took part in the Warsaw Uprising and was once again thrown into prison by the Germans. After the rebels capitulated on 1st October 1944 he was deported to a camp for forced labourers presumably in the Göttingen suburb of-Weende, where Poles were interned. It is highly probably that he was a forced labourer in a paper factory, the Pergamentpapierfabrik Rube & Co, in Weende.

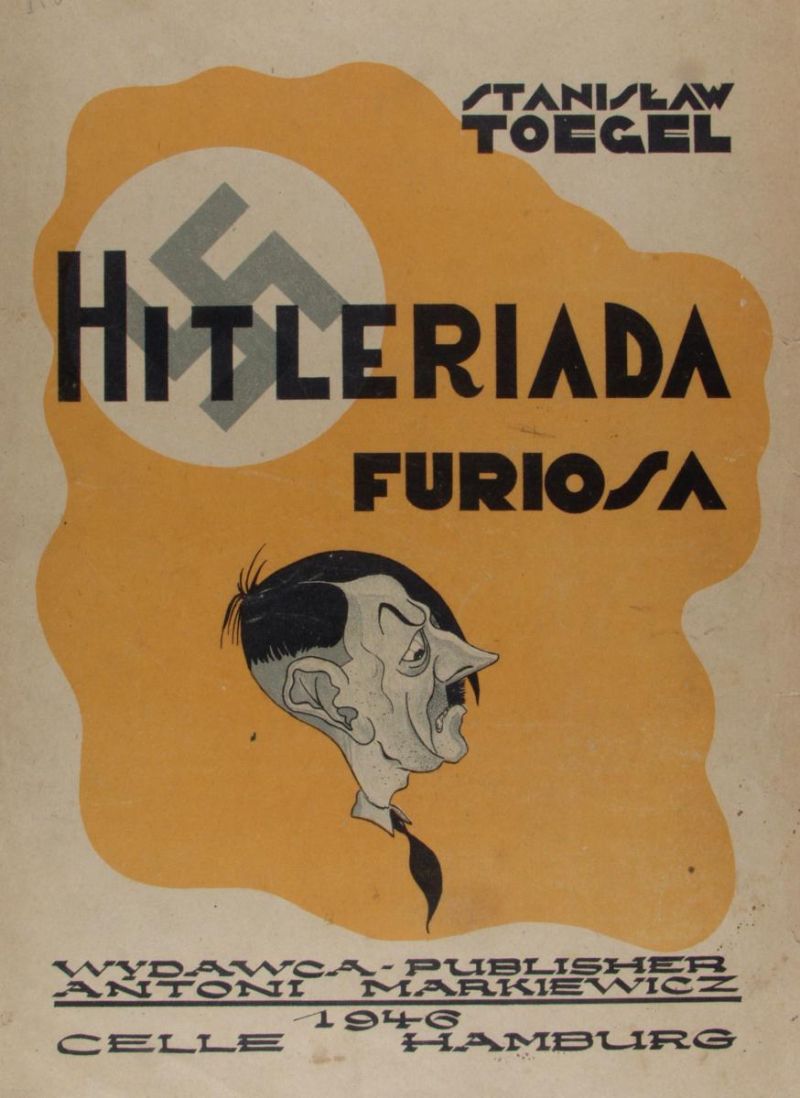

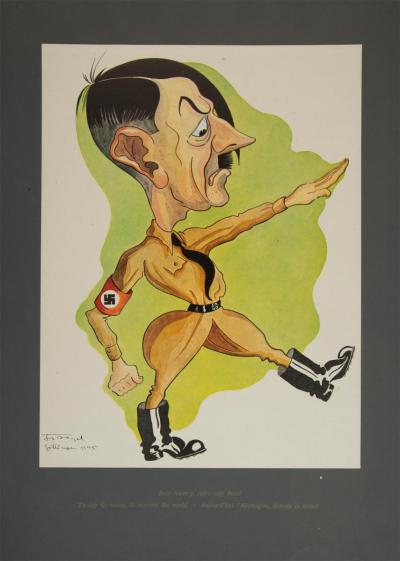

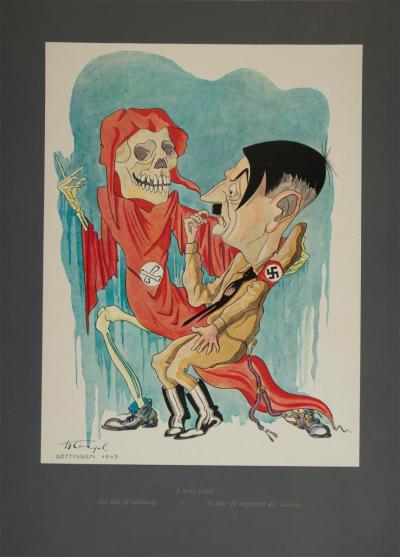

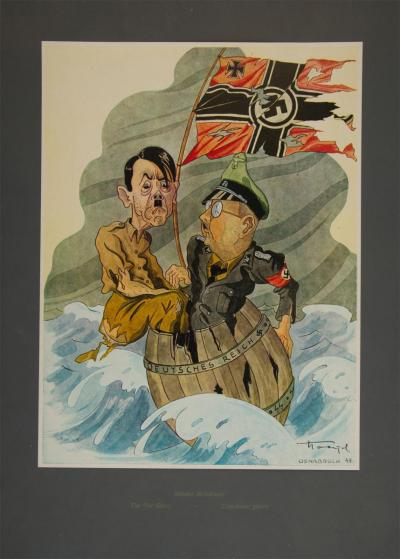

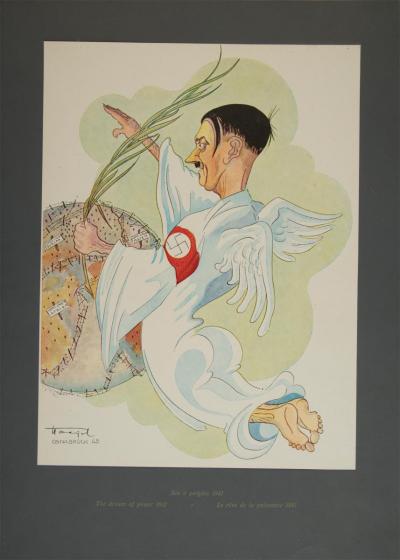

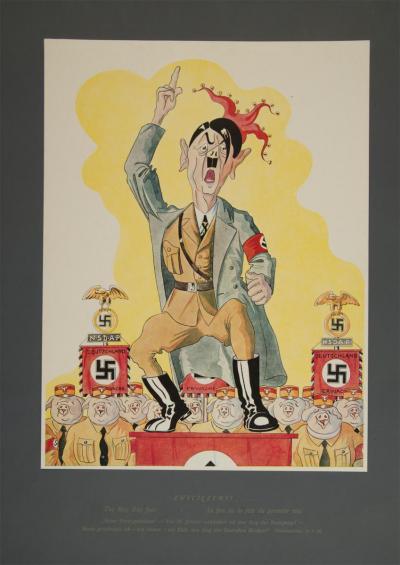

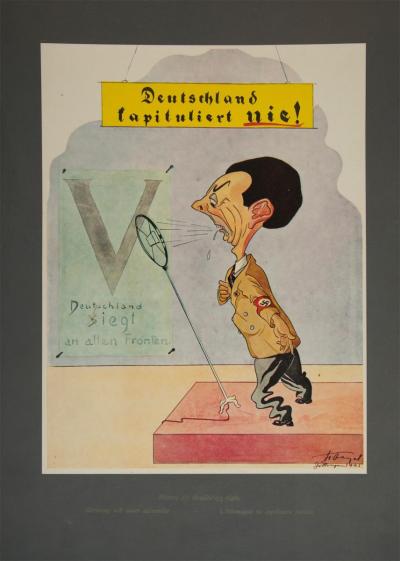

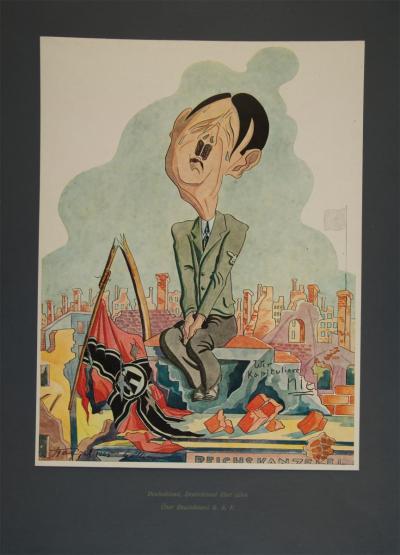

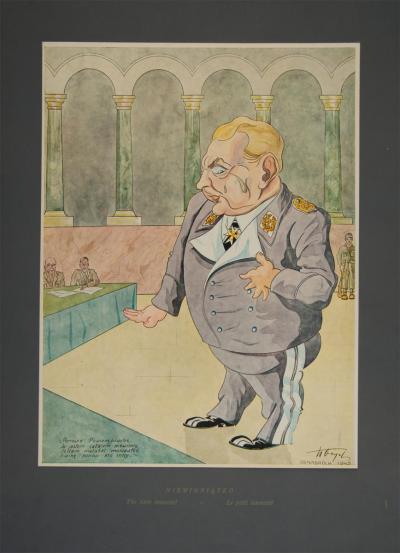

Toegel was clearly able to secrete some of the paper from the factory. “Brash sketches were rapidly made in a secret hiding […]. The notebook of a satirical reporter. The sketches circulated underground where they also fell into the hands of the Nazis who were now staring into the face of defeat.” Some of them, mostly caricatures of Adolf Hitler, Josef Goebbels, Heinrich Himmler and Hermann Göring (above all dealing with the arrogance and fall of the leading Nazis) were later part of the cycles of caricatures entitled “Hitleriada furiosa” and “Hitleriada macabra” dated “Göttingen 1945” (ill. 9/2, 9/3, 9/5, 9/8, 9/10, 9/11, 9/12, 10/2). A small heavily damaged sketch in Toegel’s estate in the Upper Silesian Museum in Bytom (Muzeum Górnośląskie w Bytomiu) is titled “Nazi Militia in Weende”“ (ill. 2).

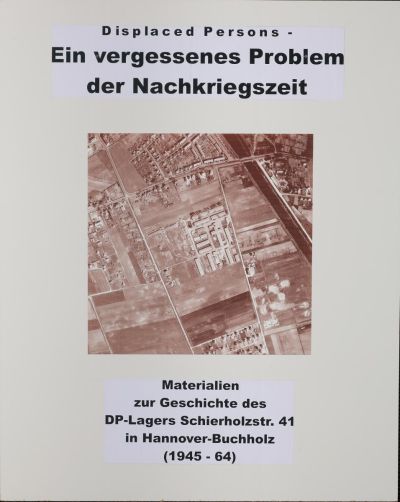

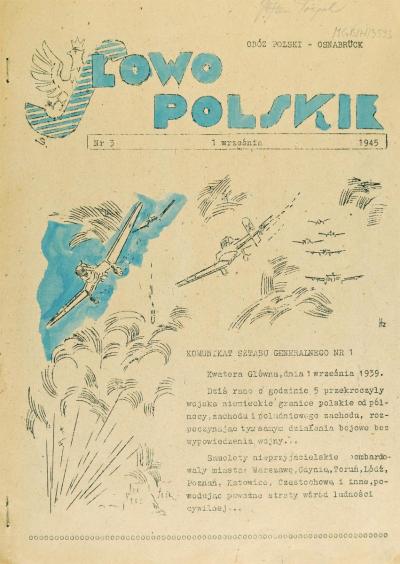

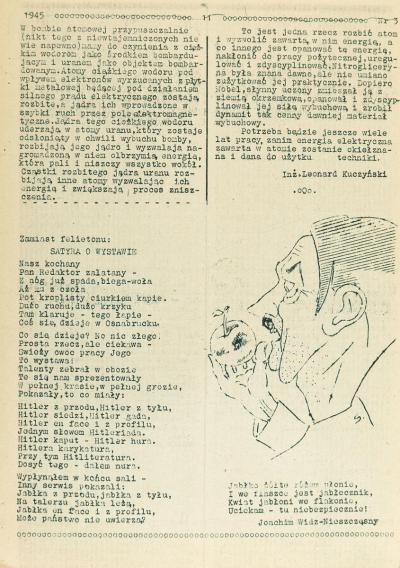

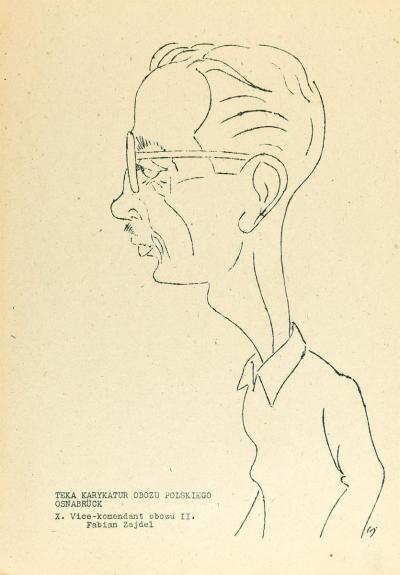

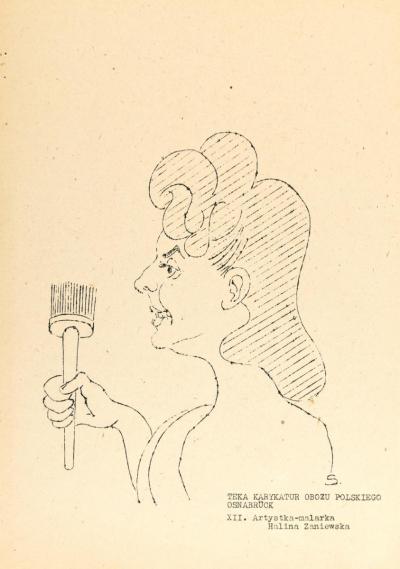

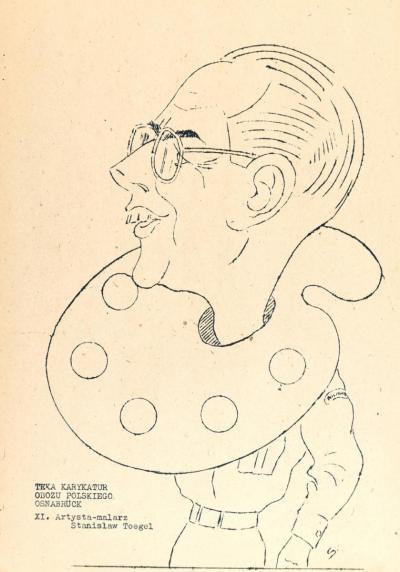

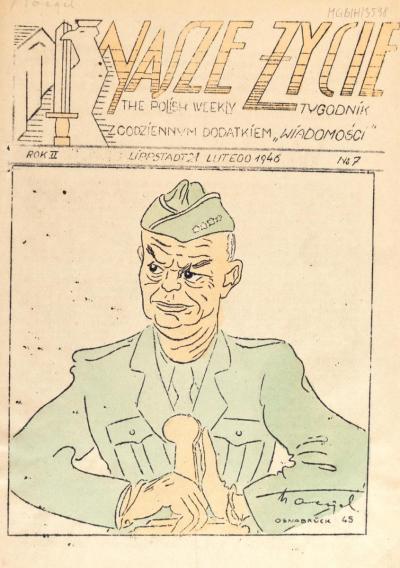

At the end of the war Toegel moved to a camp for displaced persons that had been erected by the British occupying forces in Osnabrück. Displaced persons were civilians who were stranded outside their home countries as a result of the war and Nazi brutalities and were unable to return home or wanted to settle in another country. Most of these were former prisoners of war, and internees in concentration camps. In Osnabrück three DP camps, erected in September and October 1945, housed Polish citizens: the DP-Assembly Centre, the DP-Camp “Fernblick” and the Polish Collection and Repatriation Point. In one of these camps Toegel worked on the camp newspaper Słowo Polskie (Engl. Polish Word), for which he created the title design (recognisable from the signature “S”) (ill. 3), along with a Hitler-caricature (ill. 4) and caricatures of the camp deputy commander, Fabian Zajdel (ill. 5), the painter Halina Zaniewska (ill. 6) and himself (ill. 7). He made a caricature (probably of the British camp commander), consciously and confidently signed “SToegel (ill. 8), for the title page of the Polish weekly paper, Nasze Życie (Engl. Our Life), that was published in the DP camp in Lippstadt.

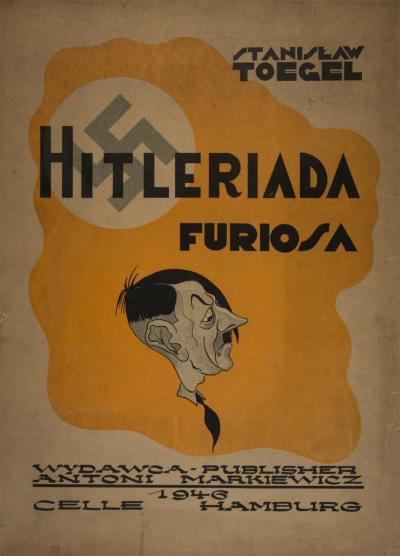

Above all he completed his series “Hitleriada furiosa” during his time in Osnabrück . The sheets not created in the forced labour camp in Göttingen all bore the note “Osnabrück 1945” (ill. 9/4, 9/6, 9/7, 9/13). In the subsequent series, “Hitleriada macabre”, only the first sheet is dated “Göttingen” (ill. 10/2), and there is no mention of any place in any of the other sheets. It is difficult to accept that the caricatures dated “Göttingen” are really the originals sketched “secretly and in haste” and later painted in water colour. The printed caricatures in both series are based on carefully executed drawings which were then painted in water colours: the dating “Göttingen 1945” simply refers to the place where he got the idea and made his initial sketches.

Both series had an offset lithograph print run of 1,450. They were printed by the Graphischer Kunstanstalt und Offsetdruckerei Emil Falke in Hamburg and marketed by the old-established Drucksachen-Handel F. W. Döbereiner in the Hamburg suburb of Groß Flottbek. The publisher and copyright holder was Antoni Markiewicz in Celle (ill. 9/1, 10/1), who was probably also a former internee in the DP camp in Osnabrück. His publishing house in Celle was clearly one of many Polish publishing houses and bookshops founded by Polish DPS after 1945. For at the end of the war there were around 1,200,000 Poles in Germany who thirsted for printed matter. Alongside Toegel`s three volumes of caricatures Markiewicz only published one book of English grammar and a book by Julian Suski (1896-1978) entitled “Rzeczpospolita” before disappearing from the scene in 1946.

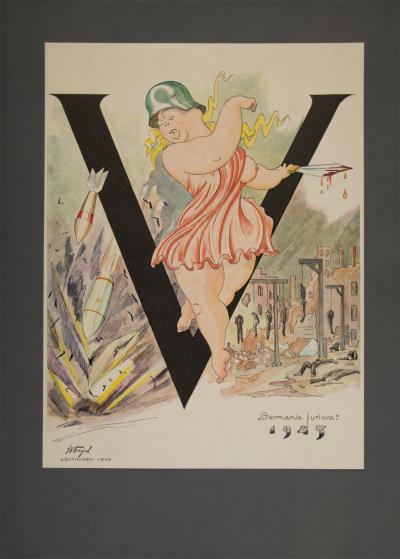

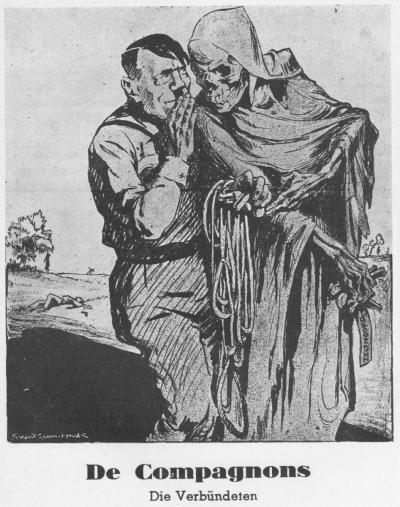

In his series “Hitleriada furiosa” Toegel’s caricatures celebrate the victory over the Nazi dictatorship by lampooning the megalomaniac fantasies of the Nazi leaders. In “Germania furiosa” (i.e. crazed Germania), he personifies Germany as a scantily dressed podgy revue dancer with a steel helmet and blood-stained dagger posing on a V for “Victory“, against a background of falling grenades, with traitors and deserters from their own ranks hanging from gallows in the ruins of a city. (ill. 9/2). An aged, skinny Hitler practices the goosestep (ill. 9/3) and a dwarf-like Goebbels (“the great Josef”) exhorts his audience to hold out, whilst a bird is shitting on a swastika. (ill. 9/4). A slobbering Goebbels with trembling knees proclaims “Germany will never capitulate!” (ill. 9/10). A desperate dithering Hitler receives the news of the day of reckoning in the lap of the Grim Reaper (ill. 9/5), whilst sailing on a stormy sea with Himmler towards their doom on a barrel with tattered German war flags and the name “Deutsches Reich”. (ill. 9/6). Hitler, dressed as a supposed angel of peace hovers over a globe strewn with concentration camps (ill. 9/7) and, clad in a fool’s cap, harangues a crowd of Nazi Brown Shirts with pigs heads during a speech on the 1st May. (ill. 9/9). Hitler, Himmler and Göring dressed as Germanic gods and armed with sword, club and axe, defend Berlin against a background of their own capitulating troops, whilst blood pours off the skeleton of “Germania” (ill. 9/11). Finally Hitler sits weeping on the ruins of the Reichskanzlei (ill. 9/12). Göring, ridiculed as “Hermann Meier” in his typical white uniform is lampooned for the empty phrase ascribed to him “You can call me Meier, if just one single enemy aeroplane appears over Germany.” (ill. 9/8) Finally he appears at Nuremberg War Crimes Trial as an innocent lamb.

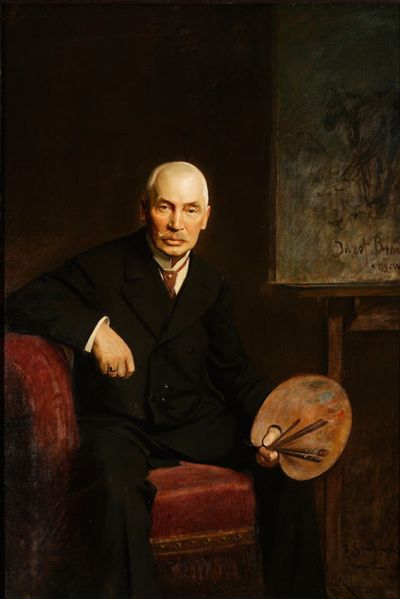

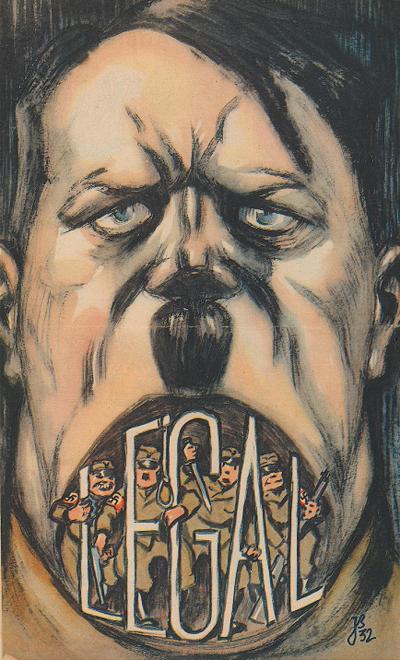

Toegel has no need to fear any comparison with other international caricaturists. Because his sketches are part of a completed cycle, they are more elaborate in their design, more polished in their portraiture, and more ambitious in their colouring than the Hitler caricatures drawn by professional cartoonists in Germany before 1933 and in the international press during the existence of the Third Reich. In Germany caricatures of Hitler and the Nazi movement could be found in the Munich satirical magazine Simplicissimus from 1923 onwards. They included works by Thomas Theodor Heine, Karl Arnold, Erich Schilling and Olaf Gulbransson. In 1929 Schilling (1885-1945) drew the first caricature of the complete figure of Hitler in the form of a swastika: it was entitled “Adolf, a Thwarted Dictator”. From 1929 caricatures of Hitler and the Nazis began to appear in the Munich literary and artistic periodical Jugend , including those by Erich Wilke (“Swastika Crusade in the Holy Land”, 1929), and Josef Geis (“The Duce Adolf up in Court”, 1930), not forgetting a huge number of caricatures by Herbert Marxen (1900-1954, “Legal High Treason”, 1930; “Posted in front of the Brown House”, 1931). The Social Democratic satirical paper Der wahre Jakob contained the most biting Hitler caricatures by far. In the edition published on 27th February 1930 the were no less than eight large-format caricatures of National Socialists, including the cartoon on the title page “Butcher Hitler” by Karl Holtz (1899-1978, ill. 9/14) and, on the back page, a distorted portrait of Hitler by the Russian painter, Jacobus Belsen (1870-1937, ill. 9/15). Between 1929 and 1933 Erich Ohser (1903-1944), drew a huge number of caricatures of Hitler and gangs of Nazi thugs for the Social-Democratic paper Vorwärts.

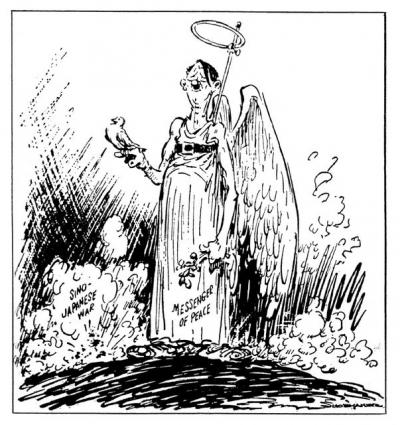

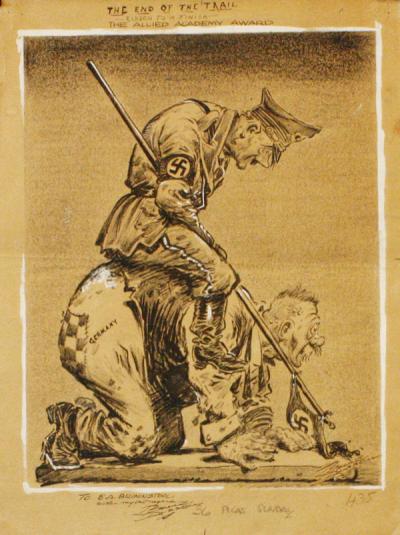

After the Nazis seized power and the German press was forced into conformity (“Gleichschaltung”) Simplicissimus and Jugend only published realistic and exaggeratedly heroic portraits of Hitler. Thomas Theodor Heine escaped from Munich and emigrated, Arnold and Gulbransson came to terms with the power elite and Schilling even began producing pro Nazi propaganda. As early as the end of 1931 Jugend stopped its attacks on the Nazis because it was afraid of losing advertising revenue. The caricaturist Herbert Marxen was subsequently sacked in August 1932. In 1933 Der wahre Jakob and Vorwärts were banned. At the same time the Nazis cultivated their own particular relationship to caricature: In 1933 the head of the NSDAP foreign press, Ernst Hanfstaengl, published a 174-page book “approved by the Führer” entitled “Hitler in World Caricatures. Deeds against Ink”, in which caricatures from the German and international press were reprinted alongside a pro-Hitler commentary. One of the caricatures in the book was originally published in 1933 in the Amsterdam Jewish paper Waak!. It showed, Hitler’s pact with the devil (ill. 9/16), a theme later reinterpreted by Toegel (ill. 9/5). In 1937, when he realised he was likely to be liquidated on account of his critical comments, Hanfstaengl fled to Great Britain. Other caricatures by Toegel also had their precursors. One of these was that of Hitler as an angel of peace (ill. 9/7). The angel can be found in the Asian part of the globe in a caricature by Vaughn Shoemaker (1902-1991), that appeared in the Chicago Daily News on the 6th November 1937 on the occasion of the Second Japanese-Chinese War (ill. 9/17). In June 1945, at the end of the war, Bruce Russell (1903-1963) – like Shoemaker, one of many Pulitzer prize-winners who drew caricatures of Hitler – published a cartoon in the Los Angeles Times, showing an aging, exhausted Hitler astride a member of the enslaved German people. (ill. 9/18). In 1941 the British artists Robert and Philip Spence published a book of Hitler parodies based on the well-known “Struwwelpeter” character, entitled “Struwwelhitler. A Nazi Story Book by Dr. Schrecklichkeit”. The book also contained caricatures of Goebbels, Göring, Stalin and Mussolini.

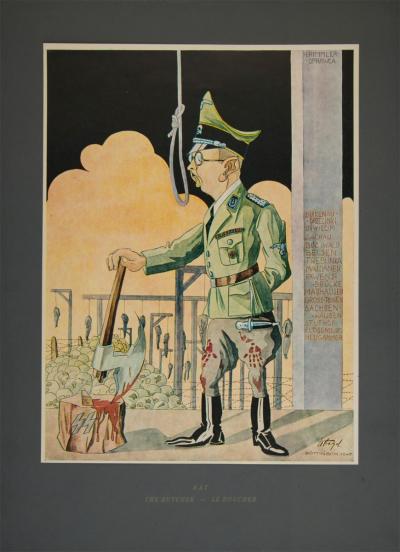

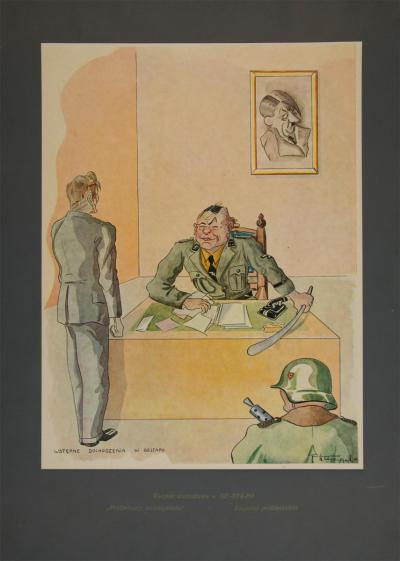

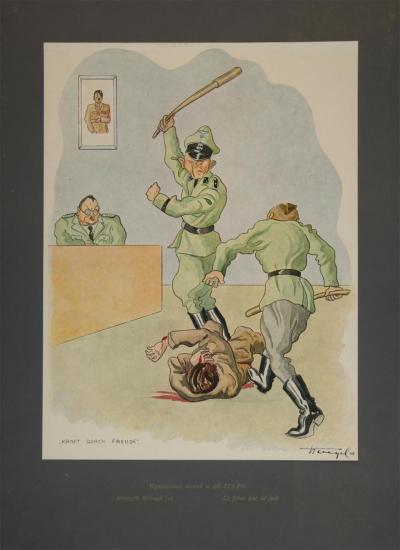

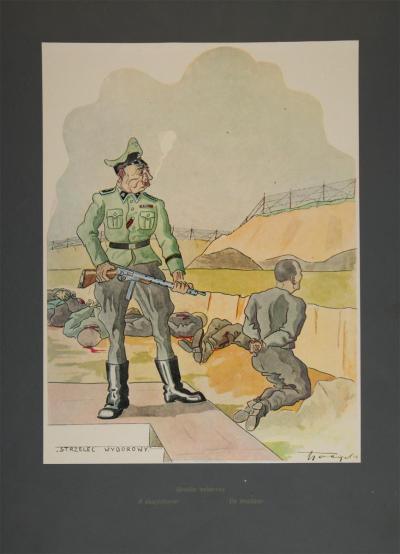

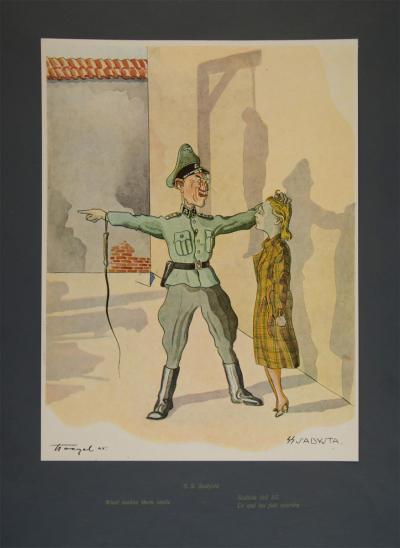

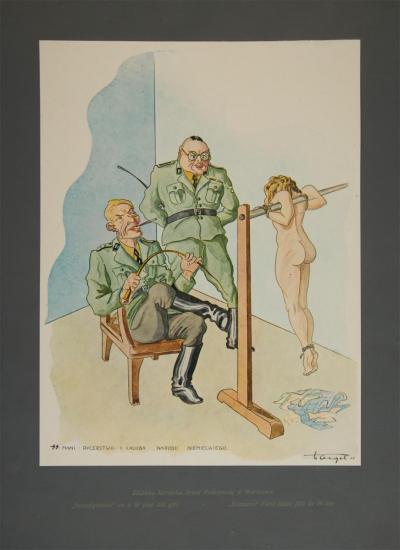

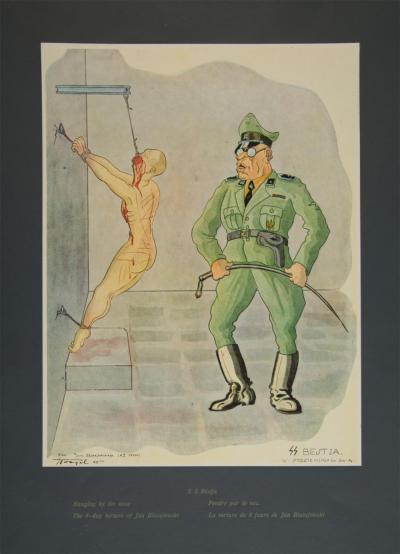

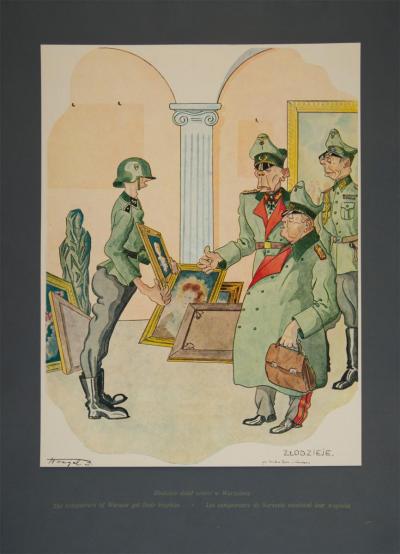

In Toegel’s next book, “Hitleriada macabre”, only the first sheet (ill. 10/2) can be regarded as a caricature in the strict sense of the word. It depicts Heinrich Himmler who, in his position as SS Reichsführer, controlled the concentration camps with his SS Death’s-Head Units. Here Toegel shows him as an “executioner” – the English and French translations call him a “butcher” – with blood-soaked trousers, an axe and a chopping block against the background of a concentration camp with piled-up skulls and victims who have been hanged. In front of his face hangs a noose through which he will shortly put his own head. On the right stands a pillar with the title “H. Himmler oprawca” (Engl. “torturer”) and a list of concentration camps. Caricatures are usually defined as working with simplification and exaggeration, i.e. satire, to display human weaknesses. In doing so, they turn their victims into a laughing stock. Toegel’s sheets use satirical drawings to portray Nazi tactics of torture, murder and robbery. The viewer realises immediately that these drawings are not at all satirical, but an unvarnished description of Nazi crimes. Interrogations with rifles and threats with truncheons, (ill. 10/3), scenes of beatings, shootings and torture are there, alongside medical experiments on a prisoner. Where there are satirical elements, these appear in the accompanying captions, for example when Toegel entitles a confession beaten out of a victim by his Gestapo torturers “Strength through Joy“ (the title of the official Nazi leisure organisation) (ill. 10/4); or when he satirises a firing squad as “marksmen“ (ill. 10/5), and members of the SS as “knights and the pride of the German people” (ill. 10/8); or when he insinuates to the “SS sadists” that torture makes him want to laugh (ill. 10/6). By contrast Ukrainian soldiers on the wall of the Warsaw ghetto, whom he describes as “accomplices of the Germans”, are caricatured (ill. 10/7); as is the scholar making a medical experiment who is exposed as a “torturer” (ill. 10/10) and the “conqueror of Warsaw” being presented with “trophies” that are in reality stolen works of art (ill. 10/11).

Contemporary viewers evaluate these scenes in the knowledge that they are symptomatic of the whole range of crimes conducted during the Nazi reign of terror. But Toegel’s point of reference was not the ghetto wall or stolen works of art, but concrete events in Poland. The Polish title of a drawing of the “examinations” of a 16-year old girl makes the reference clear: “A captured courier of the Underground Army in Warsaw“ (ill. 10/8). Toegel assigned the torture methods shown in “Hanging by the Nose, an Eight-Day Martyrdom” (ill. 10/9) to a real prisoner in a concentration camp. “Jan Błażejewski KZ 11101“, is presumably identical with the prisoner in Auschwitz with the number 11121.

As has been shown in his “Hitleriada furiosa”, Toegel’s drawings not only have a close connection with contemporary caricaturists in other countries. Because he started drawing them during his time in the forced labour camp in Göttingen (Weende) and translated his concrete experiences into the book of caricatures entitled “Hitleriada macabre”, they are also intimately connected with other collections of drawings made in concentration camps and preserved by prisoners, some of which only later fell into the hands of relatives or, by other means, into museums and memorial sites. People have long known about the four thousand drawings made by the children in the Theresienstadt ghetto and the works of the artists also imprisoned there, which now stand in the Jewish Museum in Prague, in the Ghetto Museum in Theresienstadt, the Leo Baeck Institute in New York, the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington and in many other places.

Recent discoveries include over 250 drawings made in the Buchenwald concentration camp by the French artist Paul Goyard (1886-1980), which have been held in the Buchenwald memorial site since 1998; an album containing 30 drawings made in the Dachau camp by the Polish artist Michael Porulski (1910-1989), which came to light in 2007 in the USA; 32 postcard-size sketches drawn by an unknown prisoner documenting the mass murders in Auschwitz-Birkenau (they were discovered in 1947 in the foundations of a barracks and made public in 2012 by the State Museum of Auschwitz-Birkenau (Państwowe Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau w Oświęcimiu); and lastly, the 150 drawings by the Frenchman Camille Delétang (1886-1969) made in Holzen (a subsidiary camp of Buchenwald), that were handed over to the Dora-Mittelbau camp memorial site in 2013; and which by their very nature contain similarly drastic portraits to those in Toegel’s “Hitleriada macabre”.

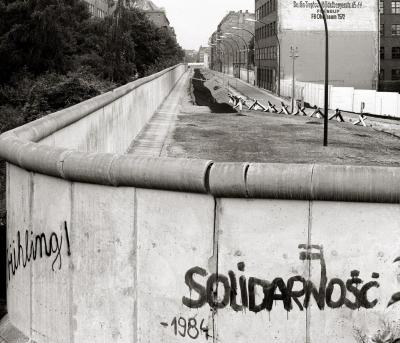

Toegel’s cycles of caricatures are also notable for the date they appeared. Since caricatures are always absolutely up-to-date, to all extents and purposes there were no more caricatures of Hitler and the Nazis in the German press when Toegel’s works were published. The order of the day was “rebuilding Germany”, “collective oblivion” new political parties and a new generation of politicians. “Where to start again?“ was the headline on the satirical paper Der Simpl, in its first edition published in Munich on 28th March 1946. The rest of the front page contained a caricature entitled “Off we go!” which showed the newly founded SPD in the form of a cleaned-up warhorse fighting for the “rebirth of democracy”. Some artists who, like Toegel, had suffered a great deal under the Nazis and the war, and saw that the “old comrades” were once more in positions of power, persisted in attacking the Nazis. As already mentioned, the caricaturist Herbert Marxen, from whose Flensburg workshop the Gestapo confiscated 200 drawings in 1938 and who fought to be rehabilitated from 1948 until his death in 1954, drew a comprehensive cycle of around 70 caricatures during this time with the bitter title “My Thanks to the Third Reich” (ill. 9/19). The Breslau-born painter Max Radler (1904-1971), who lost all his work in an air raid in 1945, started publishing caricatures of Hitler in Simpl in 1946. They showed Hitler as a recurrent “Flying Dutchman” on the alleged “secret ballot 13 years ago” entitled the “the ridiculous cabinet”, and on the post-war “mechanical denazification”, showing the Germans as “innocent lambs”.

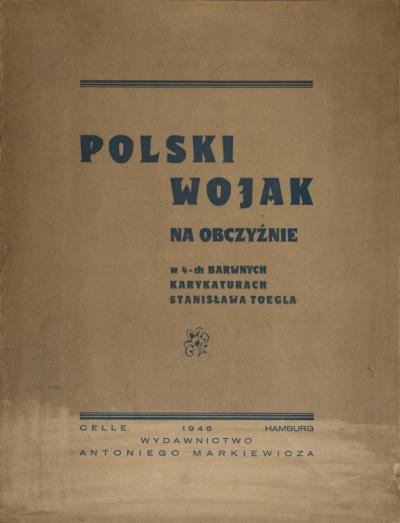

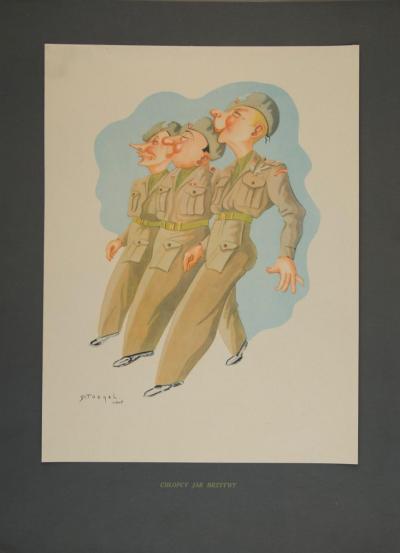

Toegel’s cycles of caricatures were in no way intended for German readers, for the foreword was in Polish. The captions on the dark grey passe-partouts were also predominantly Polish, English and French – further evidence that they were mainly addressed to Polish readers who drew their reading material from the new Polish publishing houses and booksellers in Germany. The cycles of caricatures were conceived as art folders: there existed two editions, A and B. The A series were presumably autographed by the artist, for each sheet is numbered. In 1946 Toegel’s publishing house, Antoni Markiewicz, also published a folder containing four of his coloured printed caricatures entitled “Polski wojak na obczyźnie“ (Engl. The Polish soldier abroad). He had drawn these in the previous year during his time in the DP camp in Osnabruck and they were clearly aimed at comrades there. (ill. 11/1-11/5). The sequence only appeared in Polish and to date there is only one extant copy in the Polish National Library (Biblioteka Narodowa) in Warsaw. In 2008 a sequence of eight personally dedicated, water-coloured caricatures drawn by Toegel in 1946 showed up at an auction house in America. They portray Polish and American soldiers with their lady friends.

In 1947 Toegel began working with a new publisher in Celle, Tadeusz Starczewski, who also came from the circle of Polish displaced persons. It was said that during the German occupation of Poland in 1939/40 Starczewski was head of an active underground group called Szaniec (Engl. Bulwark) in Łódź: the group was attached to the radical national underground organisation, Związek Jaszczurczy (Engl. Federation of Lizards) that had been set up in October 1939 in Warsaw. Starczewski was a student at the time, and was known by his nickname Stary (Engl. The Old One). In summer 1940 he started an underground magazine, also called Szaniec, that changed its name in December to Pochodnia (Engl. The Torch). The printing house was in the apartment of the housekeeper to the priest of the congregation of Św. Jana Chrzciciela (St. John the Baptist) in Nowe Złotno. In March 1941 the Gestapo managed to track down the location of the printing house. Whereas all the priests attached to the church were arrested and sent to concentration camps, Starczewski managed to escape from the prison in ul. Sterlinga at Easter 1941. According to Starczewski, who was born in Łódź in 1911, he had been a chief editor at the ABC publishing house in Łódź from 1934 to 1939. From 1941 to 1943 he worked as a bookseller and publisher with his own printing press. In 1943 he was arrested once more and sent to the concentration camp in Auschwitz. From there he was moved to an outside camp in the Salzgitter suburb of Drütte, and spent the rest of the war as a political prisoner – he had a “red triangle” on his prisoner’s uniform – in the concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen from 8th July 1943 to 15th April 1945. Starczewski was registered in Celle on 1st November 1945. A short time later he applied for permission to set up a “printing house and sell books and periodicals in the Polish language to displaced persons in the camps”.

The first of his publications, which he edited himself, was a magazine for the Polish inmates in the DP camp. It appeared in 1945 under the title Strażnica. Czasopismo dla harcerzy (Engl. Watchtower. The Boy Scouts Weekly for the Polish Boy Scouts Association Abroad – the scout company in Celle (Związek Harcerstwa Polskiego poza Granicami Kraju – Komenda Hufca Harcerzy [Celle]). Strażnica was also the name of the publishing house run by Starczewski in Celle. In 1947 he published several paperback titles including a collection of poems entitled “Szlak tęsknoty” (Engl. Traces of Yearning) by the Polish pilot Zygmunt Witymir Bieńkowski (1913-1979), who had been shot down over Wesel in 1945 and sent to a POW camp; “Partyzanckim szlakiem” (Engl. The Partisan’s Route) by Jerzy Szczepańczyk; “Skarb śląski” (Engl. The Silesian Treasure) by the writer and resistance fighter, Sofia Kossak-Szczucka (1889-1968); “O zmierzchu nowele” (Engl. Stories by Nightfall) by Zbigniew Topór-Krygler, a soldier in the Polish Home Army; “Nowele wybrane” (Engl. Selected Short Stories) by the Polish writer, Bolesław Prus (1847-1912); and also in 1948 a 68-page paperback in German entitled “Der kleine Betriebsberater in Organisationsfragen” (Engl. A Short Business Advisor on Organisation Questions) by Erich Gammelin. In 1948 Starczewski once mre applied for permission to publish a magazine for displaced persons in Polish entitled Strażnica ( it only lasted until 1949). In the same year Starczewski left Celle for an unknown destination, and disappeared without trace.

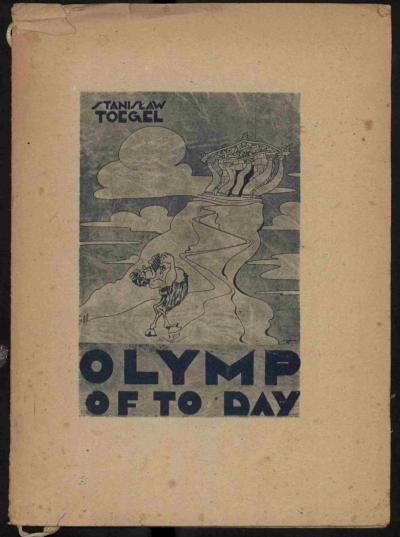

In 1947 Toegel published a further cycle of fifteen caricatures in Starczewski’s publishing house, Strażnica, this time as a booklet in black and white with a headband, entitled “Olymp of Today” (the only known copy is now in the Polish National Library with the stamp of the Polish Combatants' Association (Stowarzyszenie Polskich Kombatantów) Branch in the British Zone. The series portrays leading contemporary politicians in the act of building a peaceful new world. They are clothed in imaginary antique robes with names from Greek and Roman mythology. (ill. 12/1-12/4).

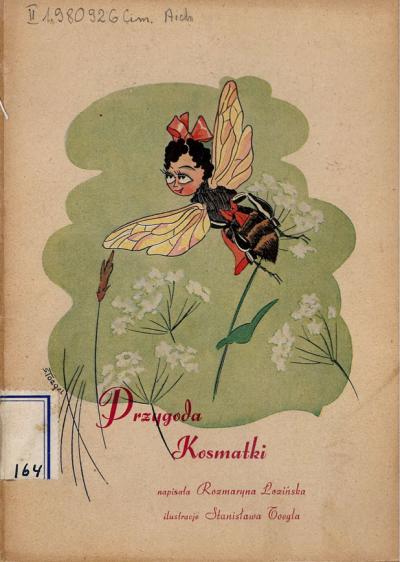

Toegel’s last work in Germany was also published in 1947 by Strażnica. It was a little book for children entitled “Przygoda Kosmatki” (Engl. Shaggyhead’s Adventures) with a text by Rozmaryna Łozińska and illustrations by Stanisław Toegel (see PDF). The heroine Shaggyhead like her sisters Stripeling, Wingling, Fatbelly and Tinybee ( in Polish they are called Pasiatka, Skrzydlatka, Gruby Brzuszek and Mioduszka) is a bee who thinks it can do everything: look after the house, fight off dangers and continue to work successfully. When the thieving wasp, Osa-Złodziejosa, attacks the house, and rain stops the bees from collecting honey, the sisters fail miserably to deal with the situation and are taunted by Shaggyhead. But Shaggyhead is also unable to fight off the attack by the little ant, Mrówka-Czarnówka. When she loses her honey, her sisters do not mock her but console her, and she promises “never to ridicule anyone again. I want to be good to everyone.”

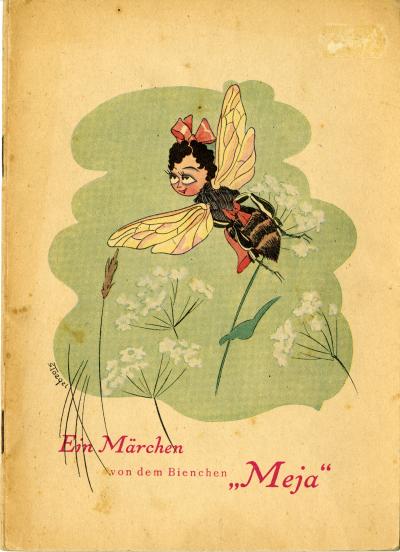

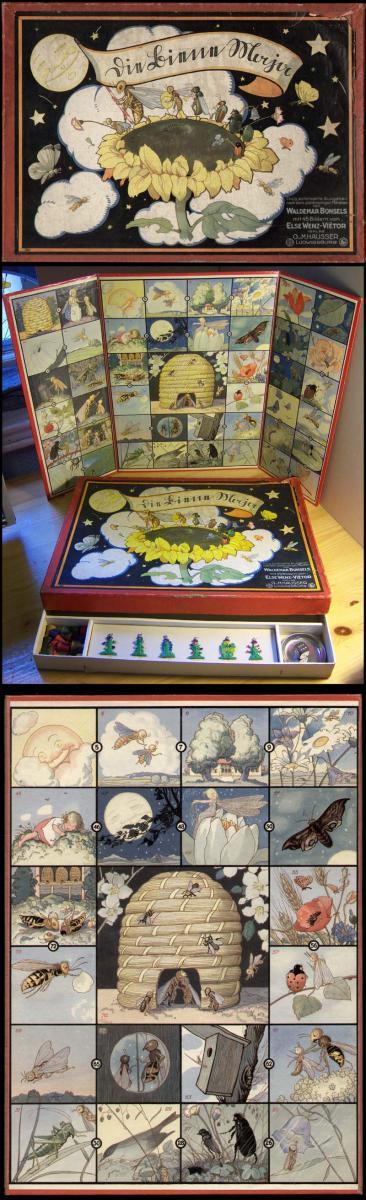

It is obvious that the book was inspired by a German novel published in 1912 entitled “The Adventures of Maja the Bee” by Waldemar Bonsel, that was published in Poland in several editions in the 1920s, under the title “Pszczółka Maja i jej przygody”. The initial indications that it was a plagiarism are the fact that its heroine was also a bee and it had the word “przygoda” in the title. But there are other indications in the characters found in Bonsel’s novel: the all-knowing teacher, Kassandra, the gang of robber ants and the warlike hornet people are all hinted at in the very much shorter version by Łozińska and Toegel. Toegel’s brightly coloured illustrations humanise the insects, not only because he gives them female heads and contemporary hairdos, but also equips them with steel helmets and rifles when he illustrates the attack by the thieving wasps. His carefully made-up ladies are similar to those in his series “Polski wojak na obczyźnie” (ill. 11/4) and in the private caricatures showing them with Polish and American soldiers. Toegel’s oversize depictions of grasses, bushes and flowers that are familiar to children’s books were not taken from any of the editions of the original “Maja the Bee” novel that had appeared by this time. However they are uncommonly similar to the 45 illustrations made by Else Wenz-Viëtor (1882-1973) for a 1920s board game entitled “Maja the Bee” (ill. 13), that might have been somewhere around Toegel at the time.

Strażnica also published a German edition of the children’s book, whose title “A Fairytale of Meja the Bee” points even more obviously to Bonsel’s model (see PDF). For whatever reason, it does not reveal the names of the two copyright holders, Łozińska and Toegel, although it is easy to decipher Toegel as the illustrator from the signatures on the pictures. Although the text sequences are somewhat changed, the differences to the original version are very slight. Meja’s sisters are now called Shaggyhead, Skinny, Honeybee, Fatty and Noddy, and at the end Meja sums up her experiences with the words: “I never want to torment others or say anything bad about them!”

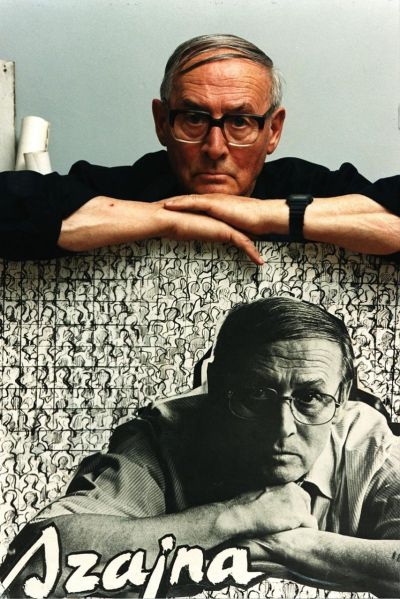

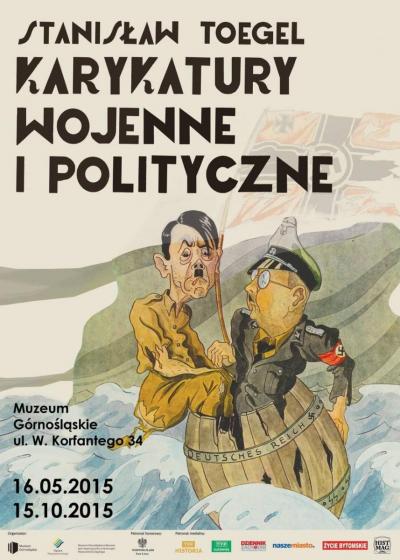

In 1948 Toegel returned to Poland, spent some time in Breslau and then moved to Bytom, where he died of cancer at the early age of 48. His first and only son was born three months before his death. In 2015 his life work was honoured in exhibitions in the Upper Silesian Museum in Bytom (Muzeum Górnośląskie w Bytomiu, ill. 14) and the Warsaw Museum of Caricature (Muzeum Karykatury im. Eryka Lipińskiego w Warszawie).

Axel Feuß, April 2016

Published works by Stanisław Toegel:

Album karykatur politycznych. Foreword by Mirosław Ogórek, Lwów (Lemberg): Druk. Narodowa, 1932 (Polish National Library / Biblioteka Narodowa, Warsaw: A.5779/Repr.XX/IV-352)

Hitleriada furiosa, Celle: Antoni Markiewicz, 1946 (Polish National Library / Biblioteka Narodowa, Warsaw: A.2176/Repr.XX/IV-67)

Hitleriada macabra, Celle: Antoni Markiewicz, 1946 (Polish National Library / Biblioteka Narodowa, Warsaw: A.2174/Repr.XX/IV-65)

Polski wojak na obczyźnie, Celle: Wydawnictwo Antoniego Markiewicza, 1946 (Polish National Library / Biblioteka Narodowa, Warsaw: A.2195/Repr.XX/IV-77)

Olymp of Today, Celle: Strażnica, 1947 (Polish National Library / Biblioteka Narodowa, Warsaw: A.4932/Repr.XX/II-376)

Rozmaryna Łozińska: Przygoda Kosmatki. Illustrationen von Stanisław Toegel, Celle: Wydawnictwo „Strażnicy“, 1947 (Polish National Library / Biblioteka Narodowa, Warsaw: 1.980.926 A Cim.)

Ein Märchen von dem Bienchen „Meja“, Celle: Verlag „Strażnica“, 1947 (Private owner)

Further reading:

Exhibition catalogue: Hitleriada Furiosa. Hitleriada Macabra. caricaturzyklen von Stanisław Toegel, Deutsches Polen-Institut, Darmstadt 2005

Marcin Hałaś: Karykaturzysta odkryty na nowo, in: Życie Bytomskie, 18.5.2015, page 13

Maciej Droń: Stanisław Toegel. Karykatury wojenne i polityczne, auf: silesiakultura.pl, 18.5.2015

Marcin Hałaś: Zapomniany karykaturzysta ze Lwowa, in: Polska Niopodległa, 30.8.2015

Webseite “Stanisław Toegel, a private memorial exhibition”, Regina Zienczyk, Bad Dürkheim: http://www.art-division.de/index.html