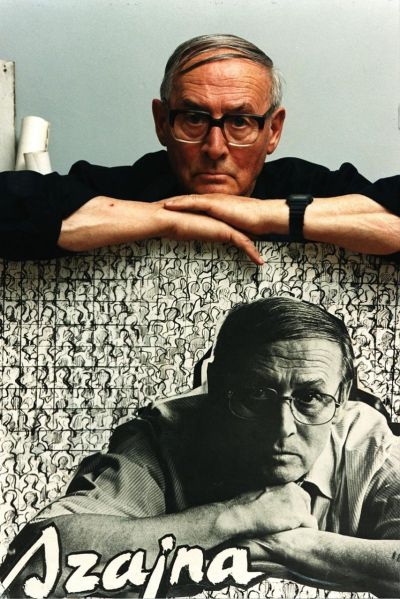

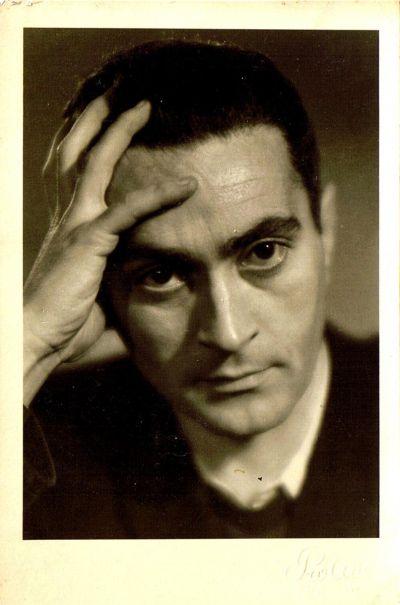

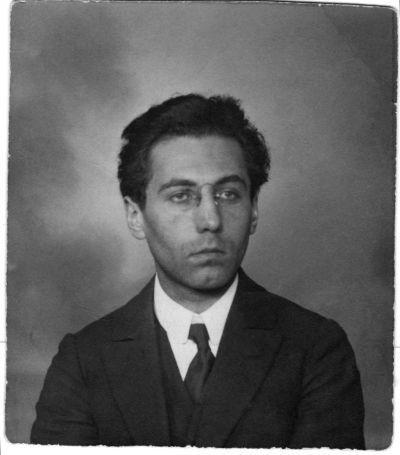

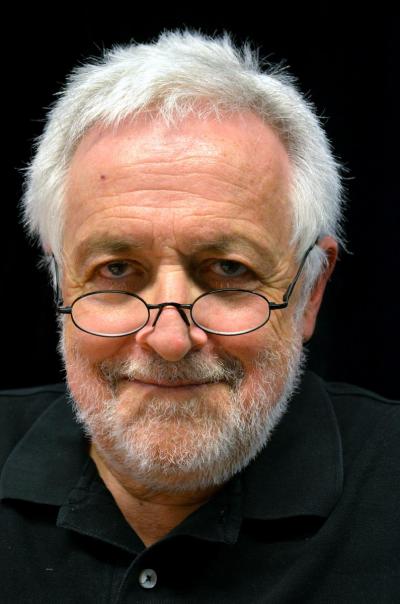

Anatol Gotfryd

Mediathek Sorted

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

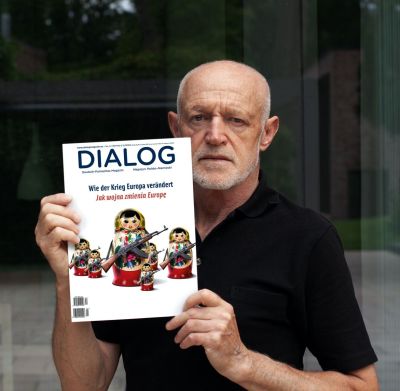

In the studio at RBB „COSMO Radio po polsku“, 5.02.2018.

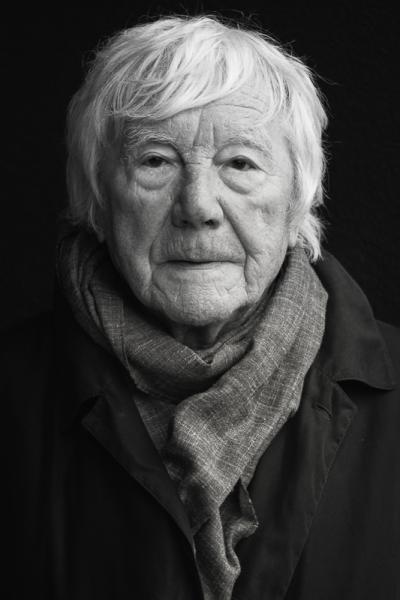

Jürgen Tomm and Anatol Gotfryd, Reading in the Berlin Buchhändlerkeller on 4 March 2018. (Extract)

Anatol Gotfryd was born on 3 October 1930 in Jabłonów, a small town in the south-eastern part of the former eastern provinces of Poland, the “Kresy” (now the Ukraine). At the time of the second Polish Republic, this region was a melting pot of Poles, Jews, Ukrainians, Germans and Hungarians. As he stated in an interview for the “COSMO Radio po polsku” programme in 2018, this multicultural society in the remote Polish Galicia shaped him.[1]

He grew up in a well-to-do Jewish family. His grandparents on his mother’s side moved to Galicia from the outskirts of Vienna. When he was barely two years old, his father died from miliary tuberculosis that he had caught from one of his patients. The young Anatol, nicknamed Tolek, spent his formative childhood years with his loving grandparents. And even though they spoke Polish at home, the family still maintained Jewish traditions. The children were given a solid education and were equipped with language skills that gave them the opportunity to go out into the world.

In 1938, Tolek moved to the neighbouring town of Kołomyja where his mother, who had just remarried, was living. At the time, Kołomyja was a lively, vibrant district town, half of whose inhabitants were Jews. One year later, this supposedly safe Gallic idyll was ruined by the invasion of the Red Army and brought to an end two years later by the German occupation. 18,000 Jews in Kołomyja, including Anatol Gotfryd’s family members, were locked away behind ghetto walls.

In autumn 1942, the Germans deported the Jews from Kołomyja to the Bełżec concentration camp where around 450,000 people were murdered. Tolek, who was 12 years old at the time, was in one of the cattle wagons in which they were transported in absolutely inhuman conditions. Many people died from the heat, dehydration and hunger in the overfilled wagons. “This is the day that I cried for the first time. Because I was one of the last to get into the wagon, I was very lucky”, remembers Anatol Gotfryd in his autobiographical novel, “Der Himmel in den Pfützen”.[2] It is only because the young boy chanced upon a place in the wagon near a door that was letting in air that he was able to breathe properly. When one of the train passengers destroyed an air grille, Tolek and his mother and father jumped out of the moving train. While he was on the run, he was stopped by a Ukrainian law enforcer. And luck was on his side once again: The policeman let him go.

After escaping transportation to Belzec, Tolek and his parents managed to get to Lwów. In Lwów, he was given a new identity and masqueraded as a Catholic boy called Roman Czerwiński until the end of the war. This he was able to do because he looked Aryan and spoke Polish. He only survived the period of German occupation and the Warsaw Uprising thanks to the care he received from Poles, Ukrainians and Germans.

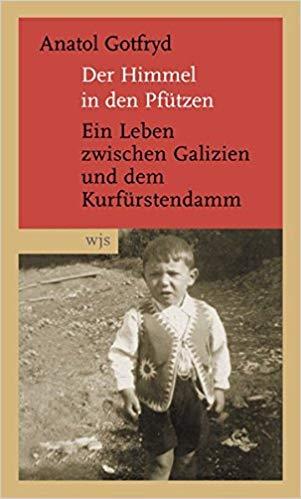

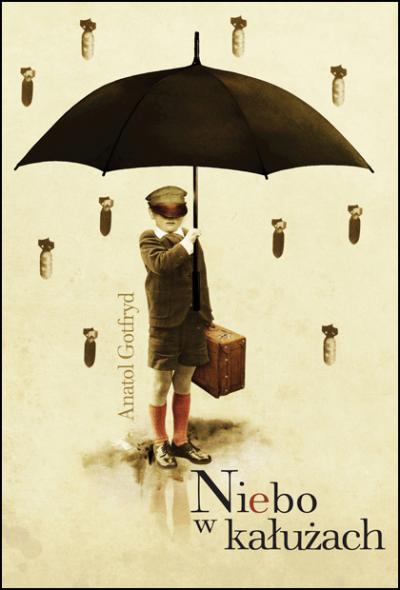

60 years later, in honour of his rescuers, he wrote the autobiographical novel “Der Himmel in den Pfützen. Ein Leben zwischen Galizien und dem Kurfürstendamm”, which was published in Germany by wjs in 2005. The Polish translation penned by Katarzyna Weintraub was published six years later by Czarna Owca under the title of “Niebo w kałużach”.

[1] COSMO Radio po polsku, 2018, https://www1.wdr.de/radio/cosmo/programm/sendungen/radio-po-polsku/ludzie/anatol-gotfryd-100.html

[2] Anatol Gotfryd, Der Himmel in den Pfützen. Ein Leben zwischen Galizien und dem Kurfürstendamm, wjs-Verlag, Berlin 2005, p. 90. [English: “Heaven in the puddles. A life between Galicia and the Kurfürstendamm”]

“I have thought a lot about people who put their life on the line to save others. Why did Bukowiecka take in four people? Certainly not for the money. (...) I believe it was a mixture of roguish audacity, a thirst for adventure and – just like Storoschtschakowa – a spontaneous willingness to help.”[3] Bukowiecka, who owned a pub on the Vistula River, hid the boy and his relatives in a small room in the Warsaw district of Mokotów for five months. And it is thanks to Storoschtschakowa that Tolek found refuge with Polish farmers and was able to help out on the farm. He even lived for a time with the deputy head of the German Police in Lwów, who was friends with Mrs Storoschtschakowa’s daughter.

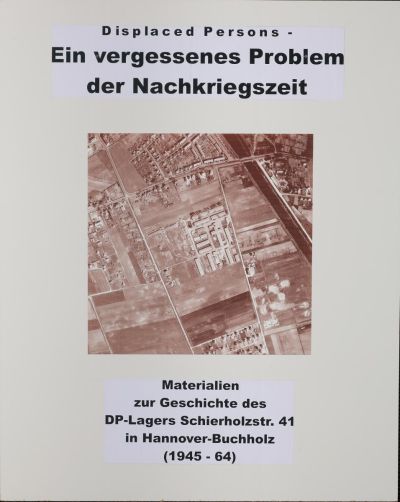

At the end of the war, Anatol Gotfryd was no longer able to return to his old home. Kołomyja and Jabłonów had already fallen to the Soviet Union. He managed to get to Lublin, where he found shelter in the Perec House, an assembly point for Jews who had survived the Holocaust. He earnt his first money by selling cigarettes on the market there. Eventually, he was able to find his parents who had left the former Polish eastern provinces. The family then settled in Katowice, where Anatol attended the Mikołaj Kopernik Grammar School.

A lucky break then meant that he was able to continue his education at a college of further education for prospective dentists, although he had missed the entrance exams. A former resident at the Perec house, who, as it turned out, was head of the examining body, recognised him and put him on the list of students. Anatol moved into the Jewish boarding school in Oławska Street, which was maintained by American aid organisations, and was appointed to the school council board. He had to step aside when the institution was taken over by the Communist government.

In October 1951, he started studying dentistry at the Medical Academy in Wrocław and was elected first-year spokesperson. It was during his degree that he met his future wife Danuta Rotkiewicz. Both of them were awarded their degree certificates in 1955.

Danuta’s father was a professional officer who had been stationed in Brest stronghold [now Belarus], where he was killed in the fighting in September 1939. The girl was very close to her father and at the time it happened had only just turned five. She would always recall the things they used to do together in the garden. Out of fear of being carted off to Siberia, she and her mother had fled to Włodawa [now on the border to Belarus and the Ukraine]. After the war, they settled in Silesia.

The freshly qualified dentists found their first jobs in Katowice; Danuta in a school and Anatol in a state outpatient department. But because they did not see a future for themselves in Communist Poland, they decided to migrate to Canada. When it then transpired that they would not be able to enter the country directly, they made the decision to go to West Berlin. It took them a year and a half to complete the necessary documents and get enough funds together. Relatives contributed 1,000 dollars which the couple used to bribe the Polish citizens’ militia so that they could get the authorisation to leave the country.

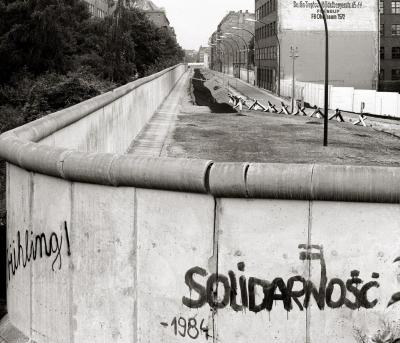

On 24 May 1958, Danuta and Anatol Gotfryd got off the train at Lichtenberg train station in East Berlin, without the slightest idea that this would be their home for the next sixty years. In the beginning, they lived with relatives in the exclusive residential area of Grunewald in West Berlin.

[3] Anatol Gotfryd, Der Himmel in den Pfützen ... , p. 121.

In his interview with “COSMO Radio po polsku”, Anatol Gotfryd explained why they chose Germany: “I didn’t feel any enmity towards the Germans. We did not equate the SS and the Gestapo with the entire German people. Some of my family came from Austria and grew up speaking this language, which is why this culture was not foreign to us. We had a lot of friends among the Germans and our family reestablished contact with them straight after the war. There was absolutely nothing exotic about our leaving for Berlin.”[4]

The Gotfryd’s took German courses and worked unofficially in various dental practices, although they often had to grapple with German bureaucracy to do so. To work as a dentist you had to have a permit to work and reside legally, which was an extremely difficult proposition for Eastern European citizens. The two of them then enrolled as free students at the dental clinic at the Free University of Berlin so that they could study for their PhDs.

A few months later, Anatol Gotfryd’s lucky streak returned. He found out that the American army was looking for dentists and that they were not asking the doctors for work permits. So he reported to the US headquarters in Clay-Allee where he took a practical professional examination. The Polish couple were then employed in the dental clinic, a military hospital, and were given the rank of lieutenant.

For the young immigrants, this was like a big win on the lottery. Their employment with the American army came with good salaries and many privileges. The doctors were provided with freshly washed surgical gowns every day as well as coats to go to the canteen where lavish meals awaited them. They even had an “errand boy” at their service. On top of this, as members of the US army they were able to buy goods that had been imported from the US in the Post-Exchange shops (PX-Shops).

Anatol worked in this clinic for a year. Danuta then took over his position and stayed in this role for a further four years. Their employment at the military clinic was an important step in the professional careers of the two dentists, not least because they learnt from the Americans how to work well. “The way the Dental Clinic was organised, the efficiency and the generous use of time and materials were unusual in post-war Europe”, recalls Anatol Gotfryd.[5] American experts often gave lectures and presented new treatment methods.

From 1949 to 1990, West Berlin was divided into three sectors that were controlled by Great Britain, France and the US. The allied powers dictated the tone of the city. The Gotfryds’ professional and personal lives were shaped by their dealings with the Americans. They were invited to lavish parties, visited the Officers’ Club in the Harnack House, the French cultural centre “Maison de France” and the University of Art and Design.

[4] https://www1.wdr.de/radio/cosmo/programm/sendungen/radio-po-polsku/ludzie/anatol-gotfryd-100.html

[5] Anatol Gotfryd, Der Himmel in den Pfützen ..., p. 220.

In 1959, Anatol Gotfryd became an assistant in the dental clinic at the Free University in Berlin where his run of good fortune continued. As a lecturer he was, in fact, a civil servant. However, when it transpired that foreigners were not allowed to have this status, Gotfryd was awarded German citizenship because the administrative act that had appointed him could not be revoked. This meant that just two years after he arrived in Berlin, he officially became a German civil servant.

At that time, a Pole with Jewish heritage was an exception at Berlin University and this aroused the interest of the University lecturers. Only a few years had passed since the end of the war in which some of the lecturers had served in Hitler’s army, and this did not make contact with colleagues any easier. Anatol Gotfryd commented on this in the interview he gave in March 2011 to Agnieszka Drotkiewicz for the magazine “Dwutygodnik”: “With them, I felt a bit like an animal that had only recently been hunted. I found it difficult to interact and to have cordial relations with the older colleagues so I kept a certain distance.”[6]

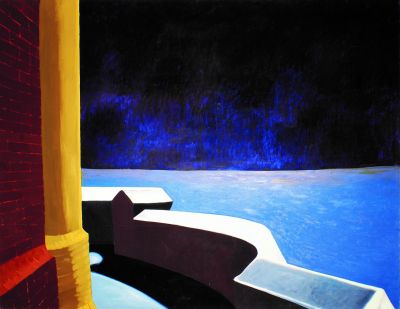

In 1962, the Gotfryds opened their own dental practice. Their decision to work for themselves was forced on them by the new regulations in the American clinic which ruled that only members of the military were allowed to work there and, unlike previously, this also applied to their relatives. The newly established private practice now gave them the opportunity to build up a patient base. The practice was situated in Lehniner Platz, just a few metres from the exclusive and vibrant boulevard Kurfürstendamm. Elegant boutiques, cinemas, clubs and restaurants, and later even the famous “Schaubühne” were all in the immediate vicinity.

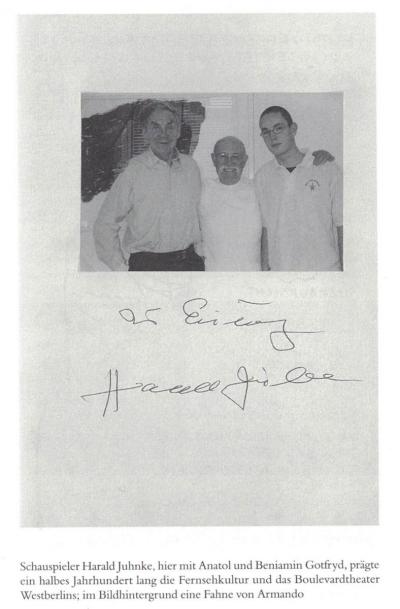

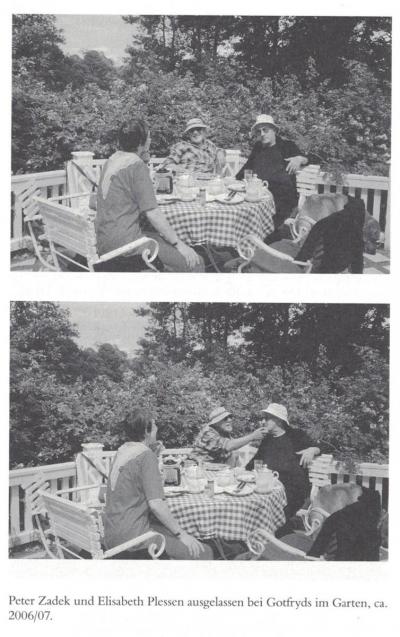

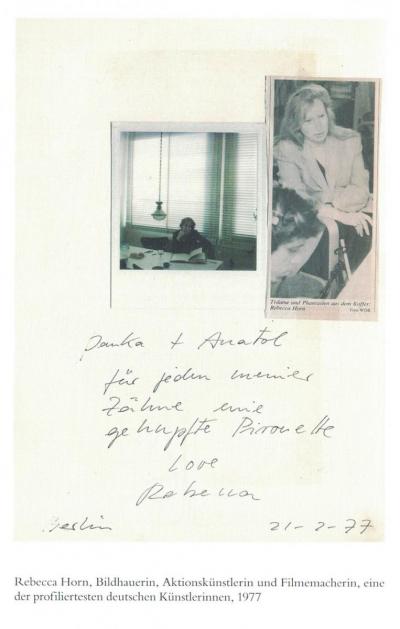

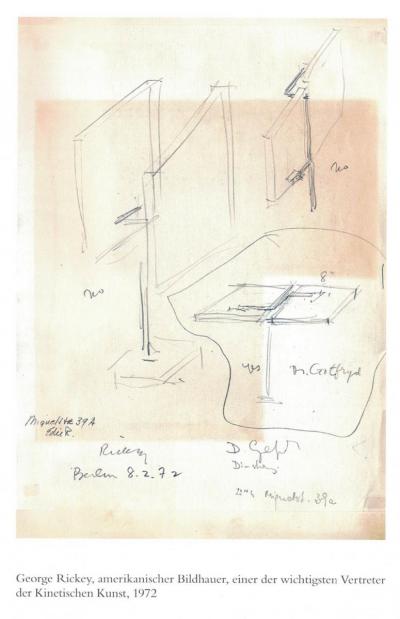

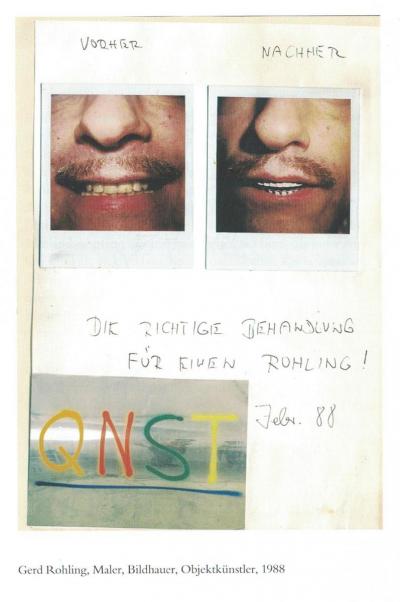

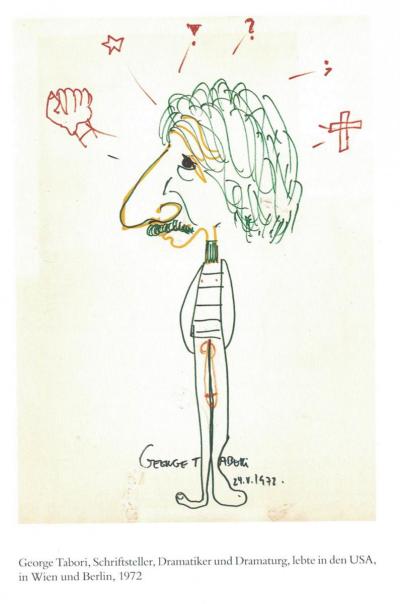

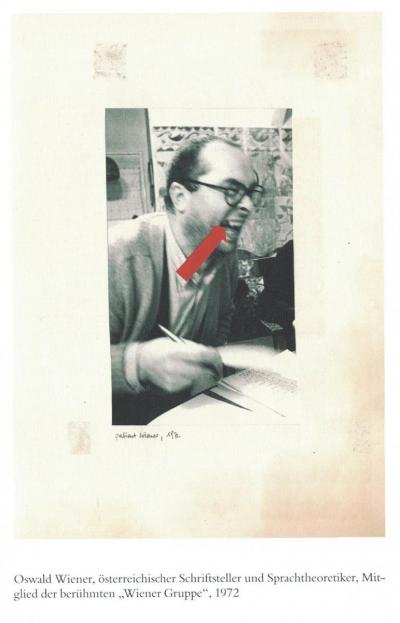

Initially, the Gotfryds mainly treated Americans until their patient list began to fill up with artists. One of their first patients was Samuel Beckett. Anatol Gotfryd devoted his second memoir, “Der Himmel über Westberlin. Meine Freunde, die Künstler und andere Patienten”, [“The sky over West Berlin. My friends, the artists and other patients”], which was published in 2017 by Quintus , to his friends, patients and artists. It contains many anecdotes from the Berlin art scene. The Gotfryds treated many famous people, including Günter Grass, Nena, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, George Tabori, Peter Zadek, Marika Rökk, Rebecca Horn, Markus Lüpertz, Katharina Thalbach, Harald Juhnke and many others.

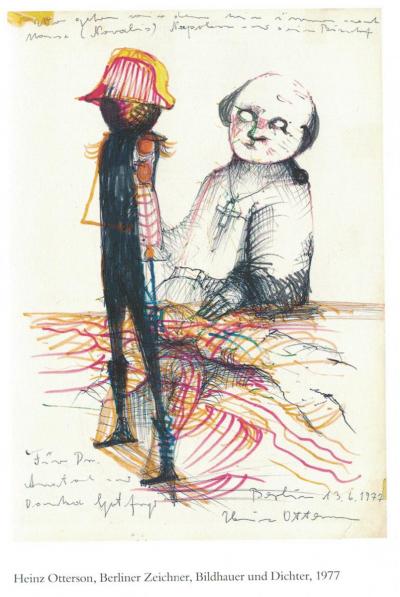

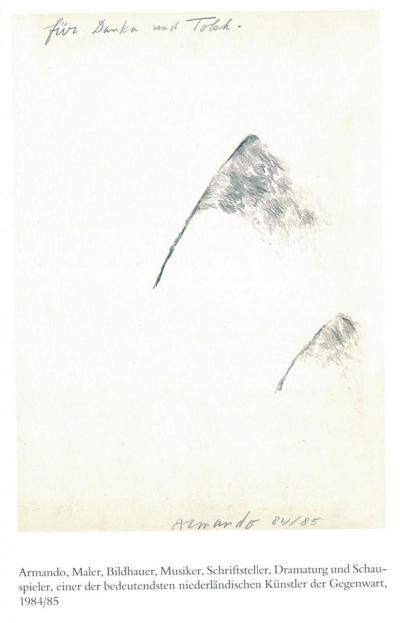

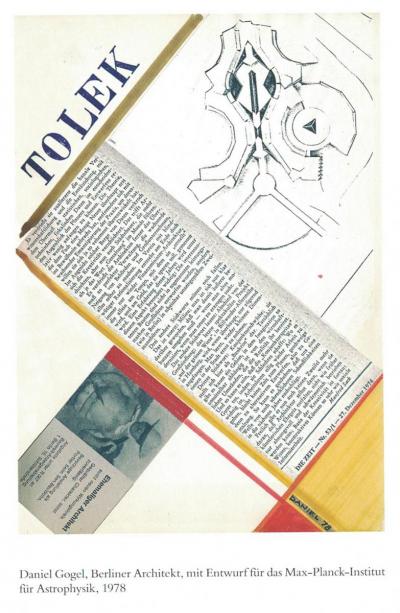

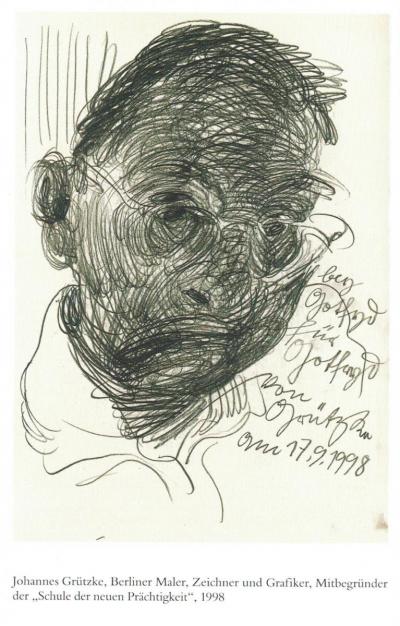

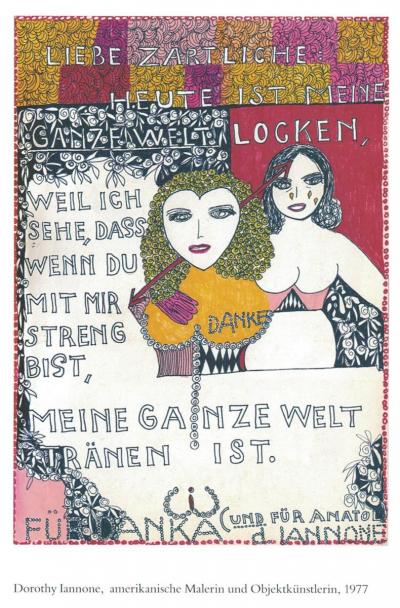

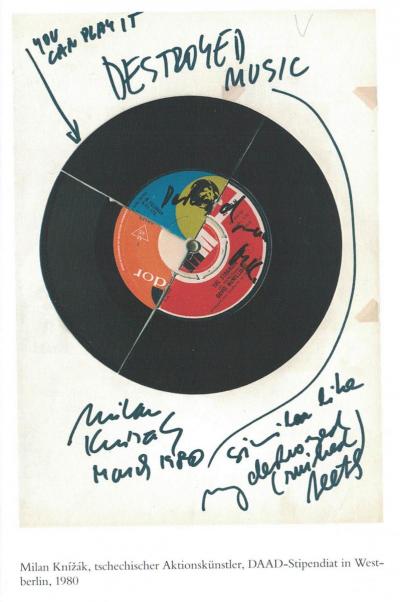

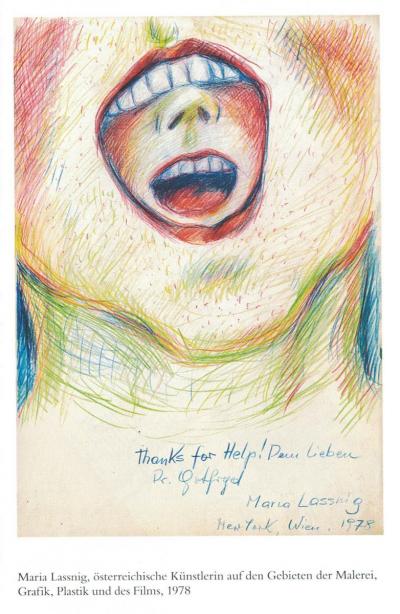

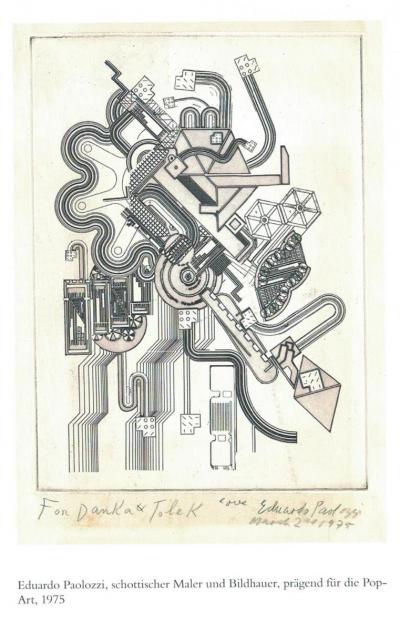

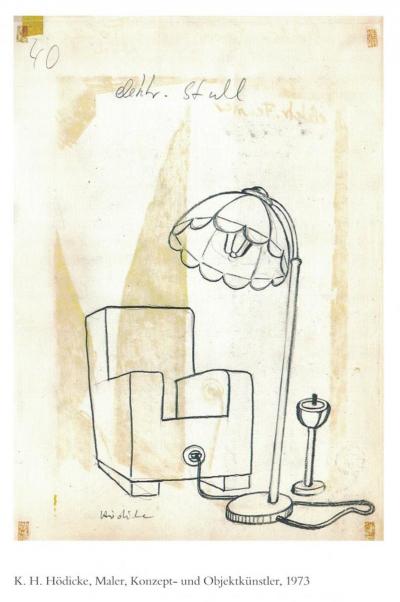

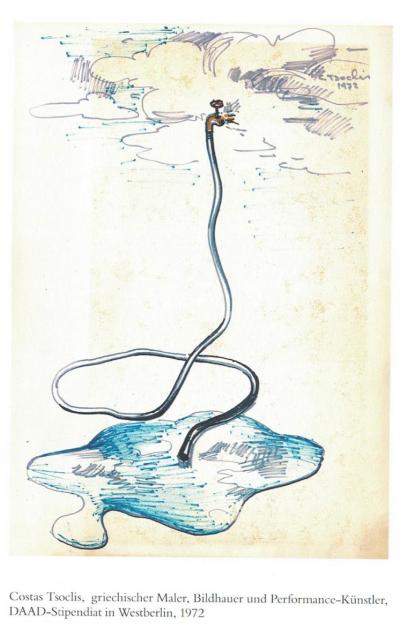

The Gotfryds set up a room in their practice as a small lounge for their friends to come for an espresso and a chat. During these visits, their friends often did drawings, read newspapers or leafed through the catalogues that were lying around. The practice also had a guestbook in which they left entries and sketches, which were often true works of art. This has become a testimony to the era documenting 40 years of Berlin culture. The book includes mementos of many famous people, such as Marina Abramović, Heinz Otterson, Daniel Buren, Allan Kaprow, Rebecca Horn, Roman Opalka, Zbigniew Herbert, Gotthard Graubner, Gerd Rohling, Maria Lassnig, Heinz Trökes, Franz Gertsch, Sławomir Mrożek and Jurek Becker.

Kaprow, Rebecca Horn, Roman Opalka, Zbigniew Herbert, Gotthard Graubner, Gerd Rohling, Maria Lassnig, Heinz Trökes, Franz Gertsch, Sławomir Mrożek and Jurek Becker.

There was a clear division of work in the Gotfryd’s dental practice. Danuta was responsible for maxillofacial surgery, parodontology and paediatric dentistry, whilst Anatol took care of prosthetics and dental retention. “Even today, I meet satisfied patients for whom we made dentures 45 years ago. When they come to see me, they want to take them out and show me”, reports Anatol mischievously and adds that the production of such custom-fit prosthetics with gold elements would be too expensive today. On top of all this, the Gotfryds were the first dentists in Germany to offer professional dental prophylaxis. Patients were delighted with the pain-free injections. Anatol Gotfryd reveals, “It wasn’t unusual for them to have a little sleep in the chair”. The two dentists placed particular importance on the efficiency of their work. If necessary, a patient’s treatment could take the whole day.

The Gotfryds’ practice was very state-of-the-art. They did not have a treatment room; instead they just had one single big room. Their patients enthusiastically accepted what was, at the time, the first dentist chair in Europe that could recline into a lying position, which the Gotfryds had imported from America. The two dentists also made sure that they continued their professional development. To familiarise himself with new treatment methods, Anatol did clinical training during his holidays at notable dental practices in Europe, including in Meran in South Tirol under Professor Federico Singer, a legend in dental medicine. Danuta also completed an additional degree in psychotherapy to better understand her patients’ behaviour.

The practice in Lehniner Platz flourished. The Gotfryds were not just excellent dentists, they were also personable and sociable, qualities that attracted their patients to them. Both are extremely warm, positive personalities, thirsty for knowledge and interested in people. Their enthusiasm is catching so it is no wonder that many patients became their friends.

In 1967, the Gotfryds moved into a property in the exclusive residential area of Zehlendorf. The crème de la crème of artistic Berlin came together in their private residence. Every Monday, they hosted soirées with billiard and chess parties, both activities being great passions of Anatol Gotfryd. Their guests included the composer and dean of the Berlin Conservatory of Music Boris Blacher, the painter and sculptor Markus Lüpertz, the architect and future dean of the Academy of Arts, Werner Düttmann, and the presidential secretary of the Academy of Arts and founder of the Künstlerhauses Bethanien, Michael Haerdter. Anatol Gotfryd was also friends with the head of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) Peter Nestler, and with the founder of the Schaubühne, Jürgen Schnitthelm, with whom the Gotfryds shared a house for 28 years, as well as with the Director of the Museum of Prints and Drawings Alexander Dückers. Gotfryd also played chess with George Tabori, the Hungarian dramatist of Jewish heritage.

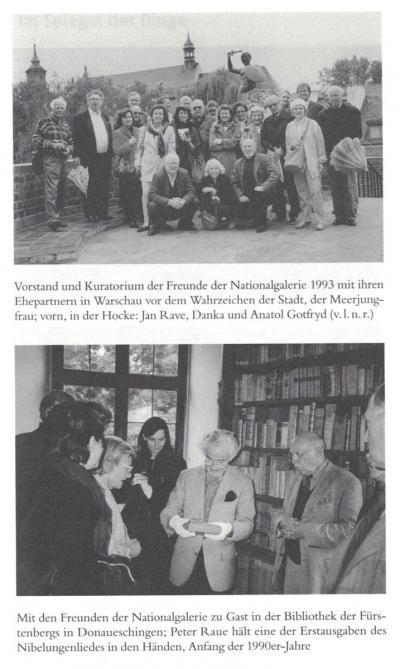

But it was not just the artists that held an important place in the Gotfryds’ life, it was the art itself. The cultural sites around Berlin became their second home. Anatol Gotfryd became involved with the Board of Trustees of the Friends of the National Gallery and with the Graphischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin. He was also one of the co-founders of the Association of Friends of the Museum of Prints and Drawings, of which he was also the deputy chairman.

In 1972, the Gotfryds bought a mansion in Berlin-Nikolassee, which had been designed and built by the Prussian architect in the style of an English country house. “It is thanks to the restorers from Poznań that we were able to rescue the house. Otherwise it would have been torn down”, explains Anatol Gotfryd. The art lover admires the proportions in the architecture. Villa Muthesius, which was built in the early 20th century, stood out for that reason.

For Danuta, whose great passion is nature, the interactions between the way the spaces function is important to her, that is to say, how the inside and the outside work together. For several years she visited parks in England so that she could recreate an English garden in Berlin. She believes that garden art is about making outdoor areas look attractive in every season. Danuta Gotfryd was awarded a medal by the monument preservation authority for this true-to-style conservation work. The architect Günter Mader published pictures of this garden in his book about 20th century garden and landscape architecture in Germany. “When one is in a foreign country, one must own a piece of one’s own land and property in order to feel at home. That creates a connection with the world”, acknowledges Danuta Gotfryd.

In the long years of emigration, the Gotfryds never lost their connection to Poland or to the Polish language. They liked to welcome Polish intellectuals, including Zbigniew Herbert, who lived with them with his wife. A warm friendship bound them to Stanisław Mrożek, whom they also visited in Poland. Stanisław Lem, Władysław Bartoszewski, Ryszard Kapuściński and Roman Opałka stayed in their home. In 1994, Anatol Gotfryd organised an exhibition of Opałka’s works in the National Gallery Berlin.

The Polish dentists ran their legendary practice until 2000. When Tolek, which Anatol Gotfryd’s friends still call him today, retired, he set himself a new goal. He wanted to stop all the people he met throughout his life from being forgotten. So the dentist became an author and has now published two successful autobiographical books. In his books he reveals for the first time how he escaped with his life during the Nazi persecutions. To that point, he had not wanted to talk about it, “…because there is something degrading and intimate about the fact of being persecuted (...)”.[7] His literary soirées in Berlin attract swarms of readers, friends and patients.

Despite living in Berlin for 60 years, Anatol Gotfryd still speaks perfect Polish, even though he prefers to write his books in German. He says that he brought the penchant for foreign languages with him from Galicia and adds: “As a child, I easily learnt a few languages – Polish, Ukrainian and Yiddish. At home, my parents sometimes spoke German. I soaked up my language skills with my mother’s milk. Multiculturalism shaped me.” The Gotfryds also found a multicultural, cosmopolitan world in Berlin, which certainly made integration and life in a foreign country easier. Sometimes Anatol still feels a longing for the “far-off, Polish Galicia”, but he decided never to return because the world, as he remembers it, is no longer there. However, he has discovered the feel of his childhood in Liguria in Italy, where he spends six months each year with his wife.

Danuta and Anatol Gotfryd have been married for over 60 years. “We are completely different. I think with my stomach, but Danka thinks with her head. But everyone who knows us, thinks that it's the other way round.”[8] And when you ask them about the recipe for a successful marriage, they say that it is based on trust, freedom and individualism. And because they always have different opinions, they never get bored. Anatol brings his wife a cup of tea in bed every morning and reads to her from books. Both agree that art and literature have always been their parallel worlds.

Monika Sędzierska