“Faithful to the Fatherland, even in foreign lands”. Patriotic telegrams from the Polish diaspora in Wrocław

Mediathek Sorted

In 1894, the celebrations of the 100th anniversary of the Kościuszko uprising were approached with particular fervour. They were held in all three occupied regions, Prussia, Russia, Austria, but achieved their greatest response in the autonomous Galicia. In Lemberg, the highlight of the festivities was revealed to be the circular painting entitled “Panorama Racławicka“ (Panorama of the Slaughter of Racławice) by Jan Styka and Wojciech Kossak. “For people in the occupied regions, it helped to ‘cheer their hearts’, it awakened feelings of national pride and it demonstrated a vision of the battle for the independence of their homeland in which the associations from the peasant masses would take part, something that ideologists and freedom fighters in the 19th century could only dream of.”[1]

Tadeusz Korzon also published the first scientifically sound biography of Kościuszko in the anniversary year of 1894.[2]

The celebrations on the anniversary of Kościuszko’s death in 1917 took on quite a different format. The events were celebrated with religious services, processions and speeches in at least 100 small towns and even in villages. And that’s how, on 14 October 1917 on the fields of Racławice on which the first battle of the uprising was won, there came to be a holy field mass and a large-scale rally, in which almost 15,000 young people, farmers and inhabitants of the surrounding villages took part, as well as a performance by the Krakow Teatr Ludowy (People’s Theatre) with a production of the play “Kościuszko pod Racławicami” (Kościuszko in Racławice) by Władysław Anczyc.[3]

Some places put on spectacular shows. These included two military aircraft, which flew over the town of Lublin raining down red and white bouquets and the pilots’ calling cards on which was written: “Kościuszko Festival on 15 October 1917”[4] In 1917 celebrations to honour Kościuszko were also held in some foreign cities, including Paris, Berville, Solothurn and Rapperswil.

It is also worth noting that celebrations were also held in the German town of Wrocław. The festival committee there worked for more than six months to ensure that they honoured the memory of the Polish national hero with dignity. The Kościuszko festival opened with a holy mass which was held on Sunday, 14 October 1917 in the church of the Mariahilf educational institution in Lehmgrubenstraße (today ul. Gliniana) which was packed to the rafters. Pastor Wilczewski delivered a spirited and extremely patriotic homily. Delegations of Polish organisations attended this holy mass waving their banners. The mass ended with the strains of the patriotic song “Boże coś Polskę” (God save Poland). There then followed an amateur performance of the play “Kościuszko w Petersburgu” (Kościuszko in St. Petersburg) in which the way the leader was interpreted by the protagonist was particularly impressive. The correspondent from the daily newspaper “Dziennik Poznański” highlighted the celebrations in his report: “In spite of the foreign surroundings, the Polish diaspora in Wrocław has demonstrated that it lives, that it feels Polish and that it will always remain genuinely Polish.”[5]

In the region of Greater Poland, which was under Prussian rule, the celebrations were held in Poznań and places such as the small town of Pleszew, where a crowd gathered around a bust of Kościuszko on a children’s playground decked out in the national colours. Red and white cockades were distributed amongst the people attending the celebrations, patriotic poems were read out, scouts sang Polish hymns and a hundred couples in Krakow traditional costume performed a Polonaise, the Polish national dance.[6]

[1] K. Olszański, Panorama Racławicka – rys historyczny (1892 – 1946), [in:] Studia Historyczne, Volume 24 1981, Issue 2 , p. 227.

[2] M. Micińska, Gołąb i Orzeł. Obchody rocznic kościuszkowskich w latach 1894 i 1917, Warszawa 1997, p. 53-55.

[3] Ibid, p. 111-112.

[4] “Kurier Lwowski”, No. 484 of 16 October 1917.

[5] “Dziennik Poznański”, No. 239 of 19 October 1917.

[6] A. Gulczyński, Harcerstwo pleszewskie do roku 1939, Pleszew 1986, p. 9.

In the second half of the 19th century, Poles, particularly those in Greater Poland, were under a lot of pressure due to the many restraints imposed on them by the occupying force, whose ultimate aim was to germanise the Polish population. This was the “longest war in modern Europe”. Meanwhile, the Poles consolidated in the spirit of national and economic solidarity. These efforts took the form of patriotic education and training for young people as well as setting an example by demonstrating reliability and conscientiousness in all areas of life. The Polish population in Greater Poland showed their opposition in a remarkable way by remaining faithful to their ideals in a clever, skilful, creative way and with resilience and cheerfulness. This was the only way they could withstand their worst and most determined, cunning and inveterate enemies, the “Iron Chancellor” Otto von Bismarck and the Deutschen Ostmarkenverband. They proved that no force in the world could drive the Polishness from their hearts.

The fight to retain their national identity took many forms. One of the most original was the issuing of decorative coloured lithographs depicting patriotic historical motifs which could be sent out to commemorate family, national or religious holidays. The were referred to as “patriotic telegrams“ or as “Kościuszko telegrams” because the first prints bore the image of Tadeusz Kościuszko. The first blank telegrams appeared in Poznań in 1895 at the initiative of Maria Łebińska, the wife of the writer and editor-in-chief of the “Wielkopolanin” newspaper Walery Łebiński[7], and of Teodora Kusztelan, the wife of the finance expert and economic activist Józef Kusztelan. The two women set up a committee to publish congratulation cards (Komitet do Wydawania Kart Gratulacyjnych), which was also known as “Women’s Committee” (Komitet Pań) or “ Poznań Committee” (Komitet Poznański). The profits from the sale of the cards were used for national, social and charitable causes.[8]

The “patriotic telegrams” spread quickly and showed a range of images of historical personalities, of heroes in the fight for independence, and of national symbols and coats of arms. To make it easier to use the pre-printed telegrams, simple, amusing texts were prepared for each occasion, which could be looked up in the book “Bukiet Dobranych Powinszowań wierszem i prozą, życzeń do Telegramów Kościuszkowskich” (A bunch of appropriate congratulations for Kościuszko telegrams in prose and poetry) published in Innowrocław.[9]

From 1912, the pre-printed patriotic forms for the telegrams were also published by Towarzystwo Czytelni Ludowych (Association of Public Libraries).[10] This institution made a considerable contribution to promoting the education of Polish inhabitants in Prussia by maintaining libraries and reading rooms with Polish literature and organising lectures and educational events. The work of this association can certainly be considered to have been passing on the intellectual heritage of Juliusz Słowacki who, in his poem “Mój Testament” (My Testament), urgently implores:

“Lecz zaklinam – niech żywi nie tracą nadziei

I przed narodem niosą oświaty kaganiec”[11](I entreat that the living do not bury their hope and

carry the light of enlightenment before the people)

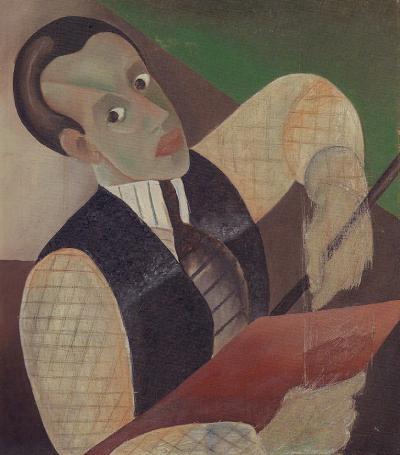

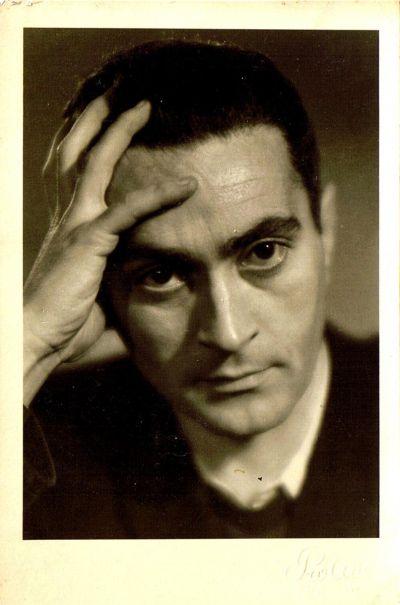

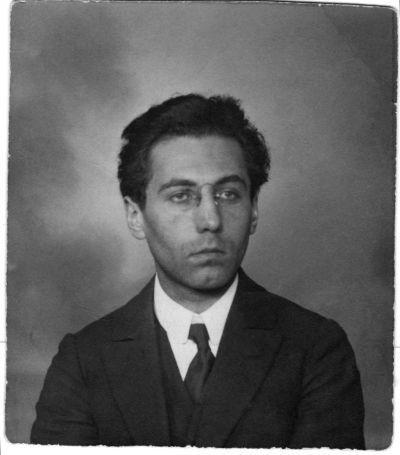

The designs for the association’s pre-printed telegrams were created by a number of artists, including Jerzy Hulewicz, Kazimierz Kościański, Tadeusz Szafrański, Franciszek Tatula, Wiktor Gosieniecki and Paulin Gardzielewski. The designs by Kazimierz Kościański (1899 – 1973), who co-founded the Poznań Group Twór (The Work) in 1933, are or particular interest.[12] His designs contain geometric lines, flat coloured areas and rhythmic compositions, embodying the forms of expression characteristic of Art Deco. His pre-printed telegrams bearing the images of Adam Mickiewicz and Ignacy J. Paderewski certainly have an artistic quality, which could not be said for all of the forms created.

[7] “Wielkopolanin”, No. 44 from 24 February 1915.

[8] K. Matysek, Telegramy kościuszkowskie i narodowe świadectwem patriotyzmu Wielkopolan, [in:] Aksjosemiotyka karty pocztowej II, published by P. Banaś, Acta Universitatis Wratislaviensis, No. 2377, Prace Kulturoznawcze VIII, Wrocław-Warszawa 2004, p. 109.

[9] J. Aleksiński, Telegramy Kościuszkowskie, Antiquitates Minutae, Poznań 2003, p. 3.

[10] J. Sobczak, Wielkopolskie telegramy kościuszkowskie, [in:] Polski obyczaj patriotyczny od XVIII do przełomu XX/XXI w. – ciągłość i zmiana, published by A. Stawarz and W. J. Wysocki, Warszawa 2007, p. 119.

[11] J. Słowacki, Dzieła wybrane, Vol. 1: Liryki i powieści poetyckie, published by J. Krzyżanowski, Wrocław-Warszawa-Kraków- Gdańsk 1979, p. 44.

[12] “Nowy Kurier”, No. 128 from 4 June 1933.

The Gabinet Dokumentów Muzeum Narodowego we Wrocławiu (Document Gallery of Wrocław National Museum) has a bundle of twelve “Kościuszko telegrams” ranging from 1913 to 1932 that represent interesting but at the same time fleeting testimonies of community life at this time. They are all linked to the work of Polish organisations in Wrocław before 1939. Their recipients and senders were national activists, people who thought and felt in Polish when in foreign lands.

Four of these telegrams relate to the Stache family, five to the Hordyk family.

The two oldest telegrams contain messages of congratulations for Franciszka and Jan Stache on the occasion of their wedding in Lubawa on 22 July 1913 in Pomerania. What do we know about the recipients?

Franciszka, née Kaślewska, came from Lubawa and took her first holy communion there on 20 September 1903.[13] Ten years later, she married Jan Stache, whose family hailed from Silesia. Jan and Franciszka settled in Wrocław where they were involved in the culture and education of the local Polish community. As an organist, Jan Stache headed up the choir in St Martins church, where the Polish diaspora in Wrocław used to gather. He was also a member of the Towarzystwo Śpiewu “Harmonia” (“Harmony” singing group). After Poland regained its independence , he worked in the Consulate of the Republic of Poland in Wrocław from 1925 to 1927. He died in 1931.[14] His wife Franciszka, who was also involved in the Polish organisations in Wrocław, was arrested on 2 September 1939 directly after war broke out, and deported to the Ravensbrück concentration camp where she remained imprisoned until June 1940.[15] The letter that she wrote to her daughter Helena Stache in Wrocław whilst in the camp is from this time.[16] Fortunately, Franciszka Stache survived the war and lived for several years in Polish Wrocław.

The first wedding telegram for Franciszka and Jan Stache shows a seemingly patriotic landscape with figures and symbols in front of an architectural folly. Two men in national costume hold a cartouche with a white eagle in their hands under which a stone tablet bearing the years of the divisions and the uprisings can be seen. Views of a town and of a village can be seen in the background. The heading bears the words “Na cele narodowe!” (for charitable causes) and below “Świadomość ludu – dokona cudu!” (The people’s consciousness creates miracles). The composition is completed by two poles bearing red and white banners on which the slogans “Oświata” (Education) and “Pilność” (Industry) can be seen on the left and “Praca” (Work) and “Trzeźwość” (Prudence) on the right. The free field below contains the words of congratulations “Sto lat, sto lat beczkę wina, najpierw córkę potem syna” (a hundred years, a hundred years, a barrel full of wine, first a daughter, then a son) which was signed by “Jabłoński and wife”. These wishes, bestowed upon the happy couple by the Jabłońskis upon their marriage, soon came to fruition: In 1914 the Stache’s first child, their daughter Helena, was born and a few years later in 1920, their son Józef.[17]

The second wedding telegram shows an arch on two columns in the middle of which an angel is depicted with the coats of arms of Poland, Lithuania and Ruthenia. The archivolt bears the inscription “Cel narodowy i dobroczynny” (For non-profit, charitable causes).

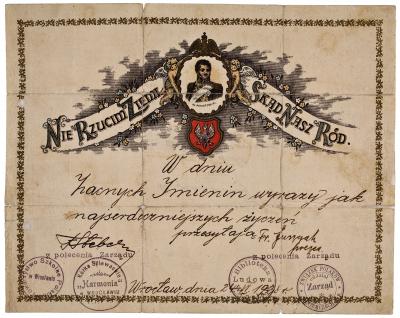

Two more telegrams delivered congratulations on the occasion of Jan Stache's name day. One is from 1928, the second is from 1930. The first telegram is decorated with an oval cartouche held by two Cupids in which the portrait of Count Józef Poniatowski is inlaid. An eagle with a crown can be seen at the top edge of the cartouche. Under this is the Polish national coat of arms on a red background. The composition is finished off by two sashes (left and right) on which the first line of the “Rota” song can be read: “Nie rzucim ziemi skąd nasz ród” (We will not give up our Fatherland). The messages of congratulations were signed by the representatives of the following Wrocław organisations Towarzystwo Szkolne Polskie (Polish School Association), Kółko Śpiewackie “Harmonia” (Singing group “Harmonie”), Biblioteka Ludowa (Public Library) and Związek Polaków w Niemczech Oddział Wrocław (Union of Poles in Germany, Wrocław Branch).

[13] The memento of the first holy communion for Franciszka Kaślewska (married name Stache) from 20 September 1903 can be found in the Gabinet Dokumentów Muzeum Narodowego we Wrocławiu (referred to below as GD MNWr.), Inv. No. XX – 797.

[14] Do nich przyszła Polska… Wspomnienia Polaków mieszkających we Wrocławiu od końca XIX w. do 1939 r., selected and edited by A. Zawisza, Wrocław 1993, p. 313.

[15] Ibid, p. 315.

[16] Can be found in GD MNWr., Inv. No. XX-795.

[17] The memoirs of Józef Stache, typescript [ca.1969] can be found in the GD MNWr.

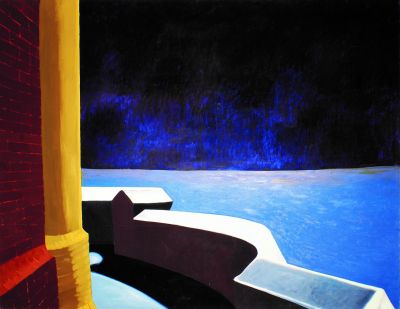

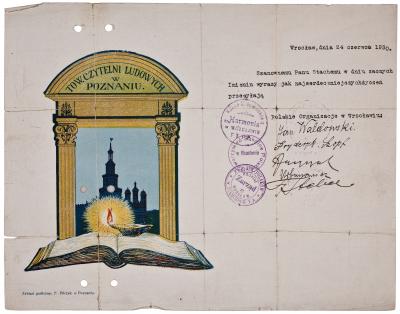

The second telegram that Jan Stache received for his name day is dated 24 June 1930 and contains messages of congratulations from the singing group “Harmonie”, from the Polish School Association and the Wrocław branch of the Union of Poles in Germany. The pre-printed telegram, which was issued by the Poznań Society of Public Libraries, shows a stylised portal in the middle of which can be see the silhouette of Poznań Town Hall and underneath, in the foreground, an open book and a burning oil lamp as symbols of education. This form is one of the most popular congratulatory telegrams issued by the Society of Public Libraries. The symbolism of the image relates to the idea of “organic work”, a term coined by Polish Positivists, for which the training and education of the masses was an important element in the fight to preserve the national identity.

Other telegrams in the Wrocław document gallery relate to the Hordyk family. Gabriela Marchwicka and Jan Hordyk were married in Wrocław on 3 February 1894.[18] Both were involved in Polish organisations: she worked at Towarzystwo Polek (Polish Women’s Association), whilst he was a shoemaker by profession and active in the Towarzystwo Przemysłowców Polskich (Association of Polnish Entrepreneurs) in Wrocław, which was largely made up of Polish craftsmen.[19] When the Polish State was reborn, the Hordyks left Wrocław for Gniezno in 1920.

The earliest telegram to members of the Hordyk family is from 1919 and was sent on the occasion of Gabriela and Jan’s silver wedding anniversary by the Association of Polish Entrepreneurs. Jan Hordyk was a long-term member of the Association and was also its managing director for some of that time.

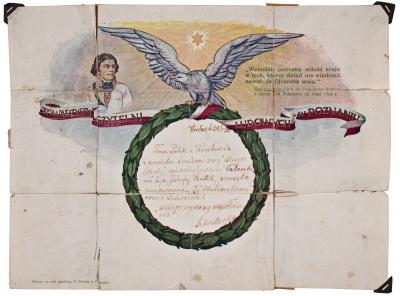

On this copy can be found a portrait of Tadeusz Kościuszko and an eagle holding in its talons a laurel wreath with a red and white sash of the Association of Public Libraries, as well as the following quote from Kościuszko: “Wzbudzić potrzeba miłość kraju w tych, którzy dotąd nie wiedzieli nawet, że Ojczyznę mają” (The love for the land of their fathers is to be awoken in those who were not aware that they have a fatherland).

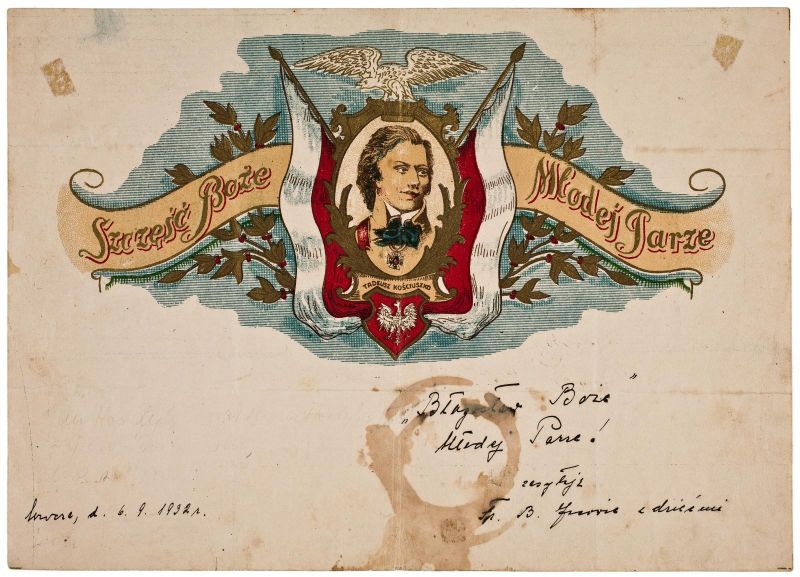

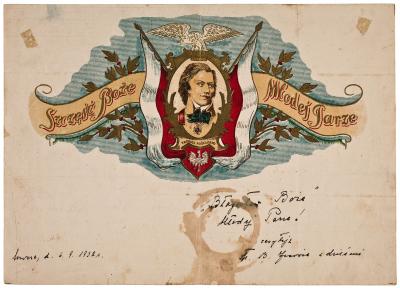

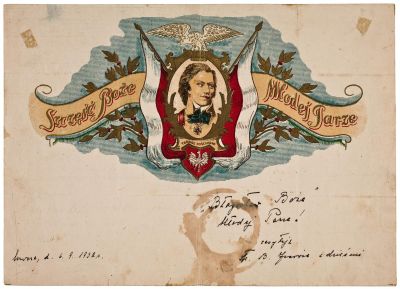

Four telegrams were addressed to Jan Hordyk and Gerta, née Zaremska, whose were married in Mrocza in Pommerania on 6 September 1932. It is assumed that the groom was the first-born son of Gabriela and Jan Hordyk. Three of these telegrams contain a portrait of Tadeusz Kościuszko, the fourth bears the likenesses of the royal couple Jadwiga and Władysław Jagiełło.

On one of these telegrams, apart from he portrait of Kościuszko, only the national colours can be seen, the others show this portrait flanked by an eagle with broken chains. They are typical wedding telegrams because they bear the inscription “Niech żyje Para Młoda!” (Long live the bride and groom) or “Szczęść Boże Młodej Parze” (God bless the bride and groom).

The telegram with the two oval portraits of Queen Jadwiga and King Jagiełło and the coat of arms of the Republic of Poland on a red background bears the words “Nie rzucim ziemi skąd nasz ród” (We will not give up our Fatherland), the first line of the “Rota” song.

In addition to the telegrams to the members of the Stache family and the Hordyk family, there are three other telegrams in our document gallery.

One, dated 24 January 1920, is a telegram of condolence from the Wrocław Polish Women’s Association to Mateusz Sentek on the death of his wife Józefa, who was a long-term member of the association. Her husband, the confectioner Mateusz Sentek, worked for many years in the Niklaus Confectioners in Ohlauer Street (today ul. Oławska) in Wrocław.[20] We are already familiar with this particular pre-printed telegram . It shows a portrait of Tadeusz Kościuszko and an eagle holding a laurel wreath with a red and white sash of the Association of Public Libraries in its talons.

The most interesting telegram in the collection of “Kościuszko telegrams”, which is kept in our document gallery, is the wedding telegram to the bride and groom of the Grajkowski family from 7 November 1925. It was sent by the Wardzyński family who lived in Bochum at the time. Władysław Wardzyński was a well known Polish activist in Westphalia. After he moved to Wrocław with his family in the 1930s, he became involved in Polish social organisations there as well.

[18] The marriage certificate of Jan Hordyk and Gabriela, née Marchwicka, dated 3 February 1894, can be found in GD MNWr., Inv. No. XX-234.

[19] A diploma for Jan Hordyk from Toswarzystwo Przemysłowców Polskich can be found in GD MNWr., Inv. No. XX-231.

[20] Quotation: Do nich przyszła Polska…, p. 287.

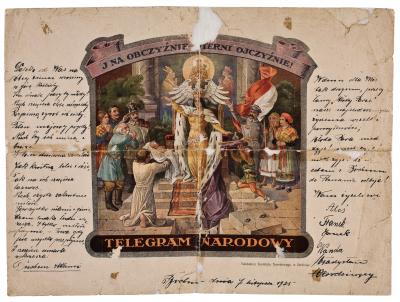

The telegram is adorned with a colour lithograph as an allegory to the resurrection of Poland along with the inscription: “I na obczyźnie wierni Ojczyźnie!” (Faithful to the Fatherland, even in foreign lands!)[21] Polonia can be seen at the centre of the composition. She is clad in an ermine coat, is protected by Our Lady of Czestochowa and a white Eagle and receives offerings accompanied by freedom fighters and representatives of the people. The Polish national flag in the top right-hand corner lends the telegram an explicit national character. The pre-printed telegram was issued by the Komitet Narodowy (Polish National Committee) in Berlin. The generous composition distinguishes the telegram as the most impressive work in the entire collection although it is very badly damaged, unfortunately.

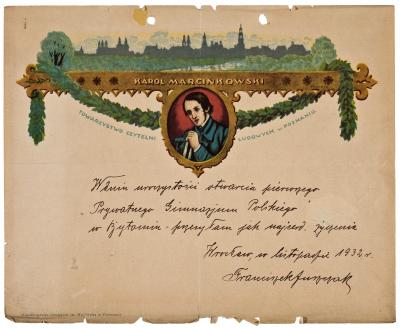

The most recent telegram is from 1932 and, like the others, has strong links to the activities of the Polish organisations in Germany. It was sent from Wrocław in November 1932 on the occasion of the opening of the private Polish grammar school in Bytom. This grammar school was the first Polish School to be founded in Germany. It was opened on 8 November 1932.[22] This classic grammar school espoused the teaching of the ancient languages of Latin and Greek. There was an understanding that: “The safeguarding of the national and cultural requirements of such a large number of Poles in Germany is the primary focus of the Polish societies and that the national and civic education and training of the younger generation are extremely important.”[23] Within a very short time, the school was extremely popular with Poles throughout Germany. The Polish community placed great value on this institution. The pupils published their own school newspaper entitled “Idziemy” (Let’s go).[24]

At the time, the sender of the telegram, the tailor Franciszek Juszczak, was the managing director of the Wrocław branch of the Union of Poles in Germany and as such was the leader of the Poles living in Wrocław. “He was a born community worker and a patriot through and through. The Polish issues in Wrocław defined his whole life.”[25] Juszczak was a charismatic man to whom the Polish diaspora in Wrocław owed a debt of gratitude for the fact that they were able to survive He preached tirelessly that “the Fatherland and the Polish people have the highest value and every strength should be invested in serving them. The equity of the Polish issue in Germany should never be called into question”.[26]

The telegram that was sent from Wrocław to Bytom contains an oval cartouche with the portrait of Karol Marcinkowski, above which the inscription “Karol Marcinkowski” is attached. Above the inscription is a panorama of the town of Poznań.[27] Marcinkowski embodied the idea of “organic work” and of the fight with the occupying forces through patriotic training of the younger generation, through education and be demonstrating exemplary integrity in all areas of life.

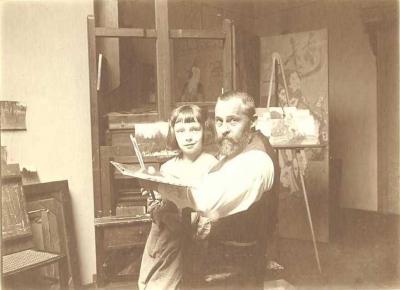

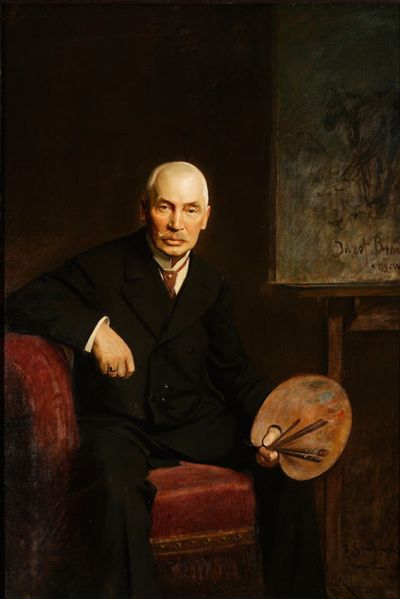

The Poznań painter Franciszek Tatula (1889 – 1946) created the design for the telegram. He was one of a dozen artists in the 1930s commissioned decorate the Polish transatlantic passenger ship MS Piłsudski.[28] Tatula also worked as a commercial artist, which included working on the “Kościuszko telegrams” for the Association of Public Libraries.

Unfortunately, we don’t know who created the remaining pre-printed telegrams from the collection in the document gallery are. It is particularly regrettable that the creator of the composition showing the allegory of Poland has remained anonymous to the present day.

The most comprehensive collections of “Kościuszko telegrams” can be found in the university libraries in Warsaw and Poznań. The Poznań collection can be accessed as a stand-alone collection through the public Internet page of the Wielkopolska Biblioteka Cyfrowa (Greater Polish Digital Library) under www.wbc.poznan.pl .

The telegrams relating to the activities of the Polish diaspora in Wrocław convey memories of people and events that are closely associated with the fundamental values, such as Fatherland, independence and language.

As evidence of the endeavours to retain the mother tongue and national traditions, the telegrams we have presented from the collection at the Muzeum Narodowe (National Museum) in Wrocław are testimony to the identity of the Poles that lived in the town on the Oder before 1939. The phenomenon of the “patriotic telegrams” is part of the legacy that illustrates the complexity of the Polish identity.

Beata Stragierowicz, August 2019

[21] A. Zawisza, Gdy mowa polska znaczyła przetrwanie. Działalność kulturalna-oświatowa Polaków we Wrocławiu w latach 1918 – 1939. Katalog zachowanych archiwaliów, Vol. 2, Wrocław 1983, p. 60.

[22] W. Kosiecki, Polskie Gimnazjum w Bytomiu, Opole 1937, S. 6.

[23] Ibid, p. 3.

[24] Issue 11 of the school newspaper can be found in the GD MNWr., Inv. No. XX-580.

[25] A. Zawisza, Franciszek Juszczak, [in:] Kalendarz Wrocławski 1986, p. 155.

[26] Quote: Do nich przyszła Polska… , p. 11.

[27] Kolekcjonerzy i miłośnicy, published by M. Starzewska, Wrocław 1988, S. 50, Illustr. 32.

[28] Polskie życie artystyczne w latach 1915-1939, published by A. Wojciechowski, Wrocław, Warsaw, Kraków, Gdańsk 1974, p. 332.