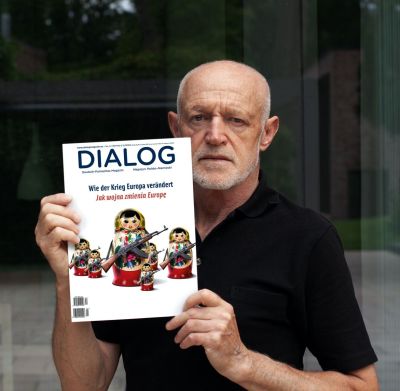

Helena Bohle-Szacki. Fashion – Art – Memories

Mediathek Sorted

Interview mit Helena Bohle-Szacki, 2012

Fashion

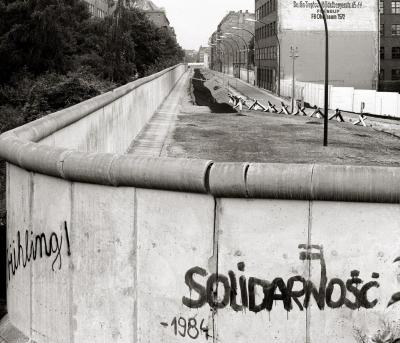

In December 1965 the following report appeared in the weekly newspaper DIE ZEIT: “Who would have thought it! The state fashion house ‘Leda’ in Warsaw is showing its latest creations in Berlin. What’s more, in the Europa-Center! Just a year ago, such a fashion show would have been regarded as the product of an exuberant imagination, as a fantasy of clothing retailers who were eager to make contact with the East. This is the first collecton presented by the Pole Helena Szacka in the West, in Berlin”.[1] The title of the Spandauer Volksblatt read “Decorous elegance from Poland”.[2] Other, thoroughly positive articles emphasized the “slightly Parisian-oriented flair” of Polish fashion and noted with a certain satisfaction the obvious influence of the Courrèges style with a futuristic touch[3], that set the fashion tone in the West in the early 1960s. That said, the distinction between East and West was never completely airtight, so that many trends and tendencies in Western fashion were also noticed and adopted in Poland.

Needless to say, the first fashion show from Warsaw in West Berlin was a political issue. It was as if the Iron Curtain which apparently finally and forever divided the political world of that time had lifted a little. The 37-year-old Helena Bohle-Szacki held a renowned position in the state-regulated fashion industry. She had not yet thought of becoming a freelance artist, nor of leaving Poland for good. Many years later she did not really appreciate her fashion activity: “Fashion as a means of expression was never enough for me, in the fashion industry I was not an artist, I may not have been a bad designer, but I was just a designer in the clothing industry.”[4]

Was this an unjustified modesty? The clothes she designed won awards in the 1960s (the gold medal in Munich, a silver at the Poznan Fair), were praised and, last not least, were very popular (when they were approved for production). Of course, at that time the fashion business functioned completely differently in Poland than in the free West. Private fashion houses did not exist and state-owned clothing companies had to contend with shortcomings in domestic industry, not to speak of bureaucratic aesthetics. There was a lack of suitable fabrics and everything else needed by the fashion industry. On the other hand, everything - or almost everything - that was produced found grateful customers. The infinitely receptive market was extremely frugally supplied. And furthermore: a kind of resistance to the grey reality of a communist country often became evident in fashion.

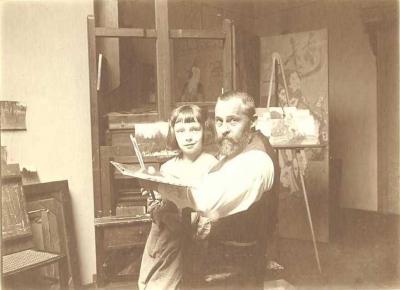

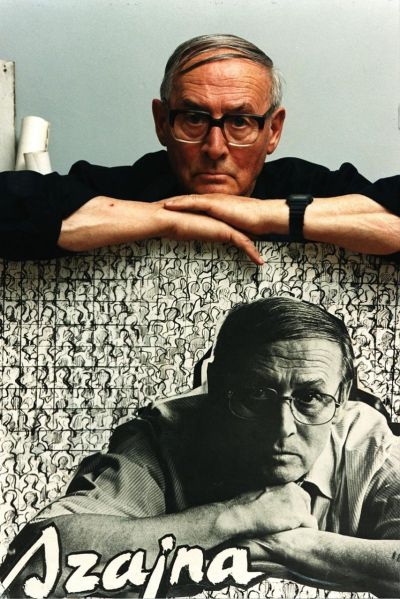

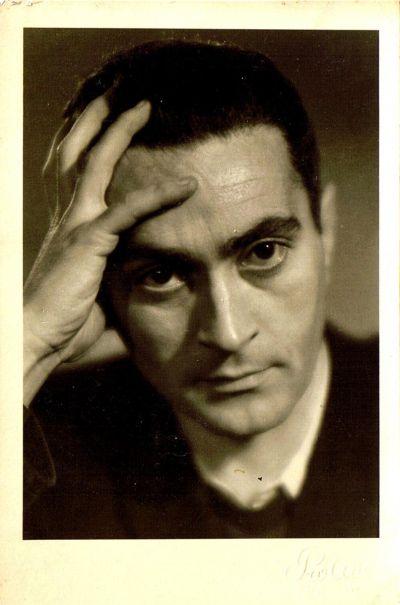

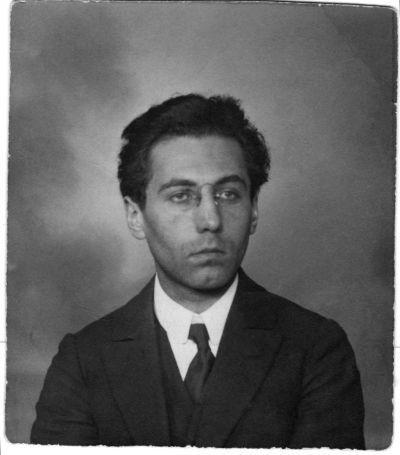

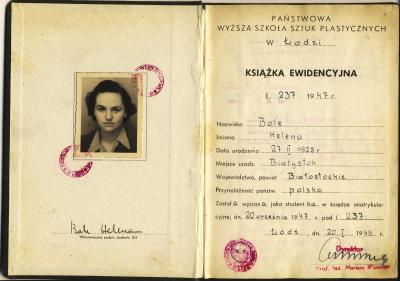

Helena Bohle-Szacki began her fashion career as a graphic artist and - as she herself emphasised - this was an occupation she followed of necessity. After graduating in graphics from the Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Sztuk Plastycznych (today: Akademia Sztuk Pięknych w Łodzi im. Władysława Strzemińskiego) / State College of Fine Arts in Lodz (ill. 2 and 3) she found it difficult to find a job. For understandable reasons, the advertising industry scarcely existed, industrial design was in its infancy, and graphic artists were only used to a very limited extent in publishing. Helena Bohle-Szacki, for example, drew images for fashion magazines whose appearance was rather bleak. After that she tried her hand as a fashion journalist, became a fashion lecturer at her alma mater and finally began designing clothes. First, she worked in the central laboratory of the clothing industry, then successively in the three state fashion houses. In the 1960s these were the most famous: Telimena, Moda Polska and Leda.

[1] “Die Zeit”, 3.12.1965.

[2] “Spandauer Volksblatt”, 28.11.1965.

[3] “Rheinische Post”, 2.12.1965.

[4] Conversation 1 with the author, Berlin 1993.

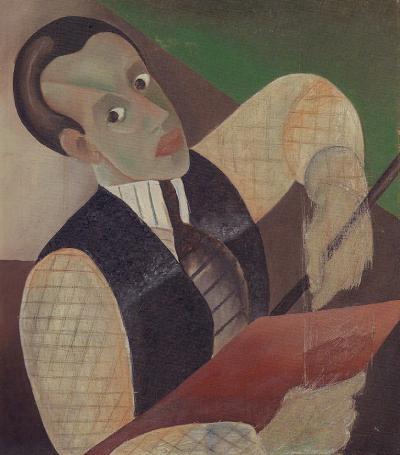

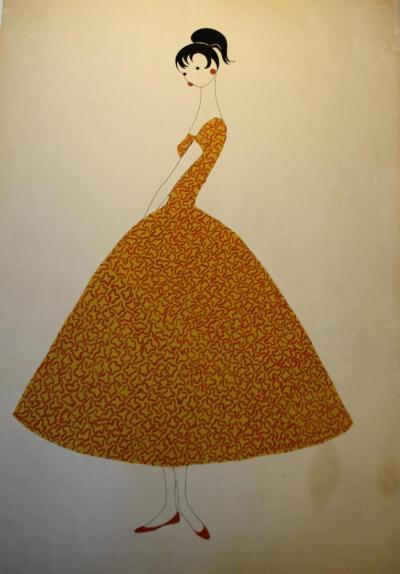

Having studied with the famous advocate of constructivism Władysław Strzemiński, whom she particularly admired, the prospective fashion designer was inspired by him. “Like Strzemiński, she considered art to be closely linked to industrial production and transferred painting ideas to textiles. She believed that fashion was a kind of art that serves everyday life and is created within a network of all artistic areas”[5], wrote the fashion journalist, Marcin Różyc and quoted Bohle-Szacki‘s reflections: “One of the most important questions when designing clothes is to fall back on and draw on purely artistic problems, such as contrasting forms, differentiating the surface structure, and taking account of the colour composition”. It is therefore no surprise that some of the fabric patterns in her designs appear to be taken from a unistic picture by Strzemiński (ill. 4). Later she incorporated distinctive neoplasticism (which Strzemiński also cherished) into fashion, as evidenced by a summer collection from the Leda fashion house in 1966. (ill. 5, 6) And nonetheless: throughout her life Helena Bohle-Szacki was never given the recognition she deserved. It was not until 2017 that the aforementioned journalist and art historian Marcin Różyc rediscovered her achievement. He now analyses and propagates the special status of the once-forgotten fashion designer.

After leaving Poland in 1968, she was to see for herself that the huge success of her fashion show in West Berlin was primarily of political significance. Armed with her German passport (her father’s inheritance) Helena Bohle-Szacki started looking for work. In doing so, it became only to clear to her that she was no longer regarded as a diva of fashion from Communist Poland, but merely as an unfortunate emigrant from the Eastern bloc who had chosen freedom in the West - as she told her friend the journalist Anna Hadrysiewicz many years later[6]. Now she was anxious to integrate and ready to make the most of her skills and abilities. She wrote several hundred applications, which finally brought her a job as a director at the Kittke und Sohn company, a “specialist in skirts”. It was not long before she became disillusioned.

Talking about her professional beginnings in West Berlin, she said: “The work was deadly boring. We produced skirts. For example, I was given a pattern and had to make about fifty variations: sometimes with a different bag, sometimes with a different button or clasp, etc.”[7] She made involuntary comparisons: “Taking this company as an example, I was able to observe the difference between the two economic systems for the first time. In Berlin it was all about profit with a minimal financial investment. In communist Poland, fashion was a kind of joke, an utterly unreasonable activity. Here you had to make at least twenty designs a day, there - there, a dozen a month.”[8] Creativity was not in demand, but rather “skill and taste”, as shown by her job reference from the “skirt specialist”.

Was it also this disappointment that inspired her to distinguish herself as an artist? She put up with the assembly line work with skirts for almost six months. After that she taught at several adult education centres where she lectured on fashion and interior design, until she finally found a position as a lecturer in graphics and visual communication at the vocational school of the Berlin Lette Association.[9] Now she was materially secure, had more time to herself, and the yearning to express herself as a free artist became all the more urgent.

[5] Marcin Różyc, Teoria mody, in: Helena Bohle-Szacka. Lilka. Mosty / Die Brücken. ed. M. Różyc, Białystok 2017, pp. 65–73.

[6] Anna Hadrysiewicz, Rozdział berliński, in: Helena Bohle-Szacka. Lilka. Mosty / Die Brücken, ed. M. Różyc, Białystok 2017, pp. 219–236.

[7] Anna Hadrysiewicz, at the specified location.

[8] Ibid.

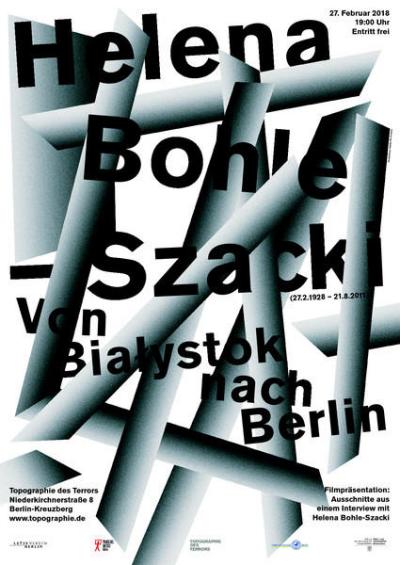

[9] For the event to mark her 90th birthday on 28.2.2018 in the Topography of Terror, a group of students from the “Lette-Verein” prepared some sketches for the poster; see ill. 7.

Art

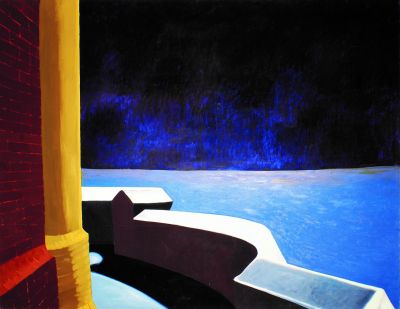

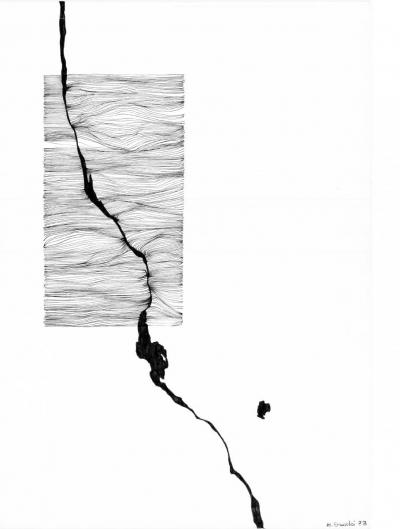

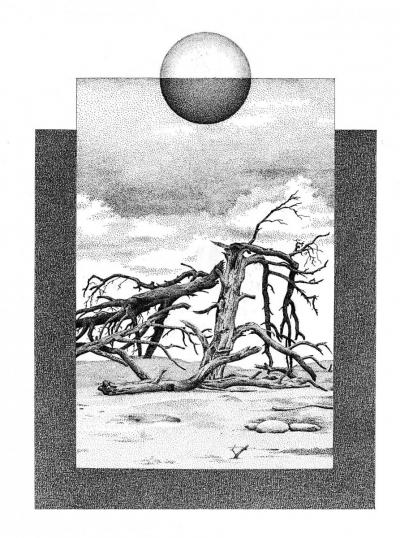

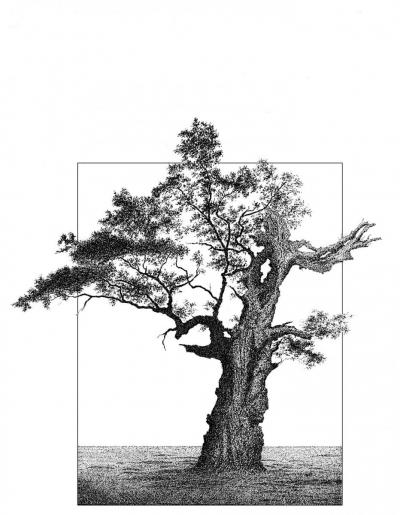

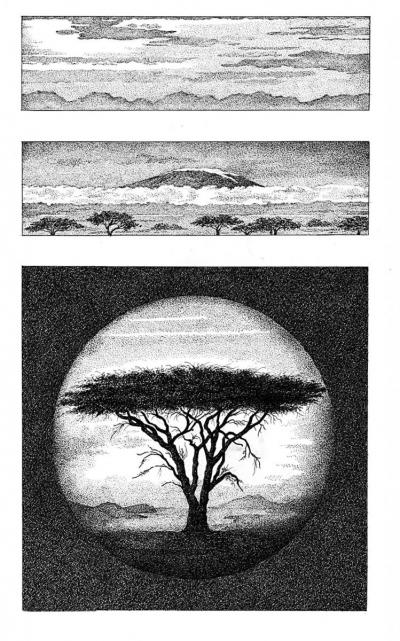

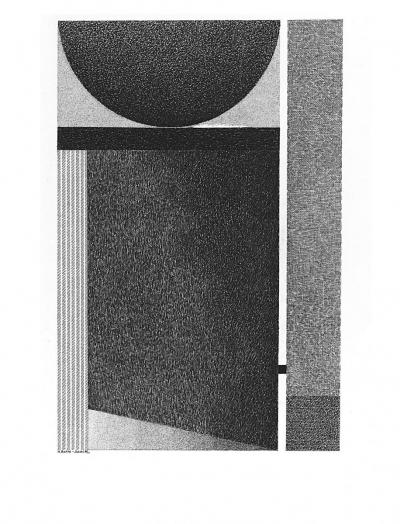

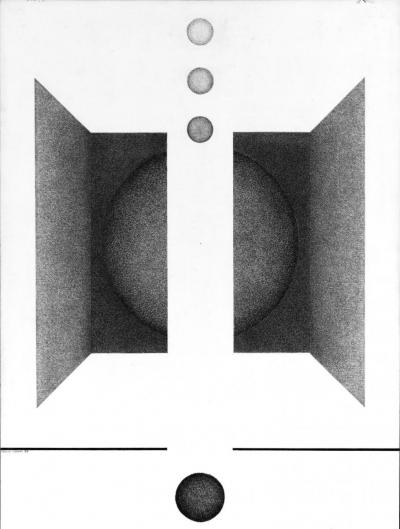

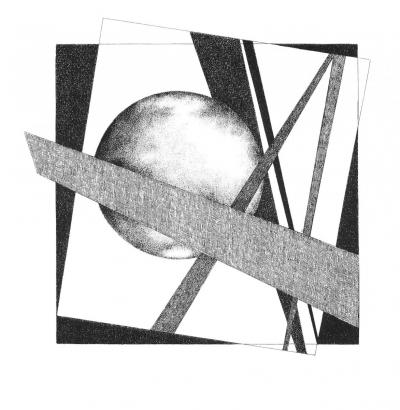

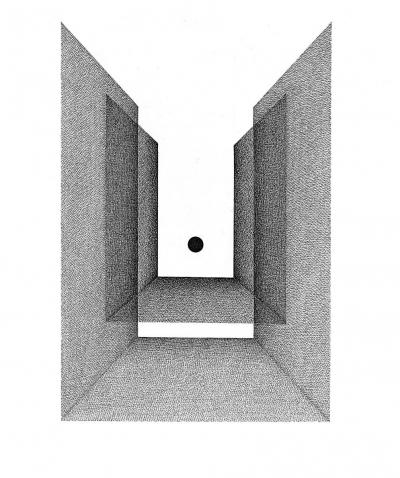

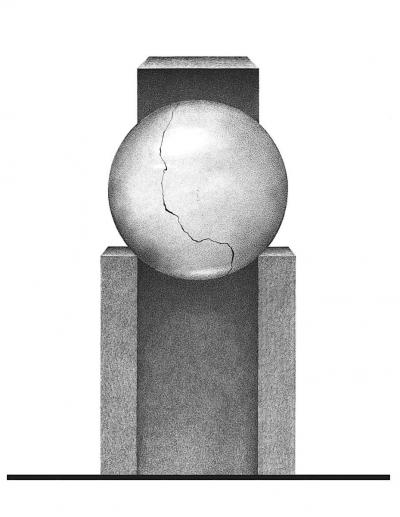

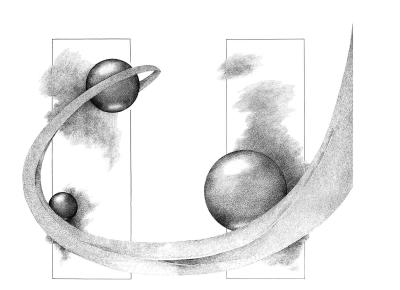

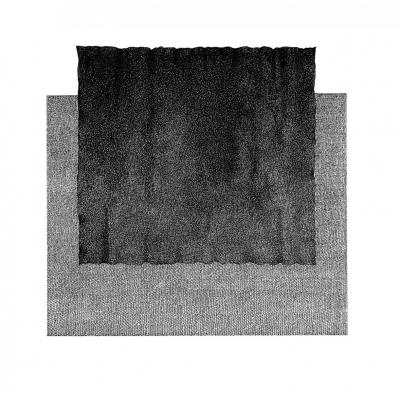

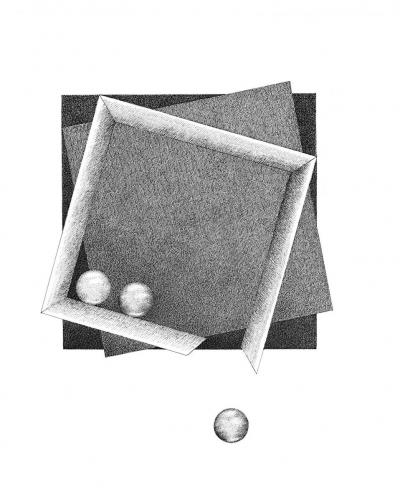

In the early 1970s she began to take art seriously. Until her death she created more than 300 drawings on paper and cardboard. Her oeuvre comprises several motifs, some of which differ considerably from each other: They are geologically or organically inspired pictures, portraits of trees and sections of landscapes, all the way to abstract geometric compositions. (ill. 8–24). But this development was by no means linear, and in turns she took up different themes, mixed them together, sometimes allowing the narrative in the picture to take precedence, and at other times devoting her energies to more emphatic abstract questions. “For example, I try to achieve certain dynamics and depth with the help of an erroneous, crazy perspective. But through this formal problem I also want to express my own world. In everything I do, there is great respect for the cosmos, but at the same time it is also a vaguely perceived mysticism and the awareness that our petty existence is not so important,” said the artist.[10]

Art critics, artists, and publicists who have commented on Helena Bohle-Szacki‘s work have sought different approaches to her pictorial world, drawn on metaphors and formulated their own interpretations, some of which do not entirely agree.

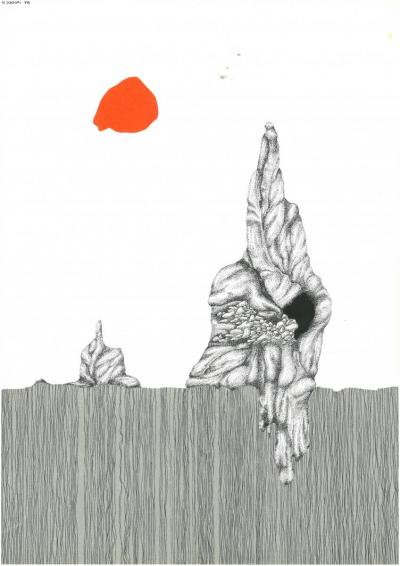

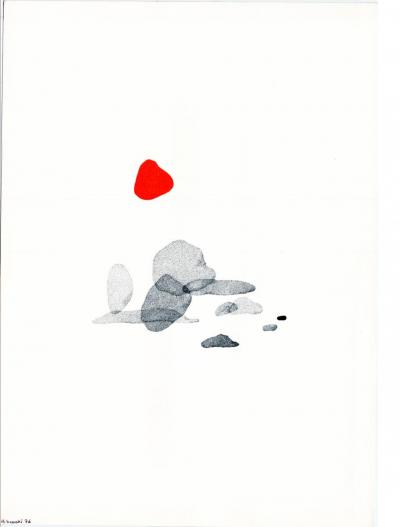

Katarzyna Siwerska, an art historian and co-curator of the exhibition “Helena Bohle-Szacka. Mosty / Die Brücken”, which was shown at Białystok Galeria Sleńdzińskich from June to August 2017, writes about Bohle-Szacki‘s first Berlin works as follows: “What distinguishes the abstract paintings from the 1970s and the early 1980s is their open composition. Some elements seem to want to flow off the sheet at any moment. She draws cocoons, knots, biomorphic marks whose streamlined contours resemble shapes in nature. The misshapen figures are like excrescences, new formations, degenerations. The artist blurs the line between the worlds of the human and the plant.”[11] However, the writer and journalist Andrzej Więckowski, author of the text of the catalogue for her Berlin exhibition in 1994, noted: “In her early works, the artist dealt with the inner dynamics of forms as if she had caught evolution in the transition from a geological to a biological form”.[12]

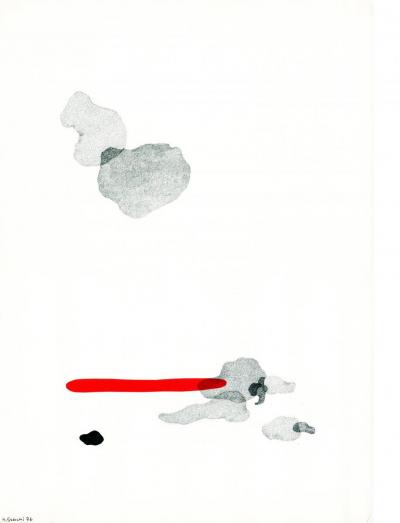

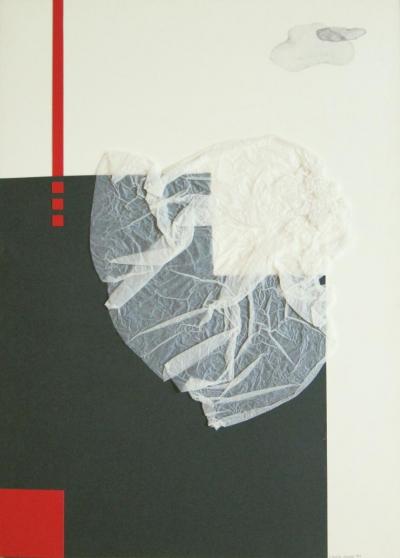

During her first creative period Helena Bohle-Szacki produced paintings using mixed techniques. She drew with a pen, made collages with white tissue paper or aluminium foil, and added red spotty elements or stripes to the black-and-white drawings. Over time the biological abstractions and the colour gave way to figurative motifs drawn in black and white: Tree trunks, broken branches, rock formations and stones appeared on the pictorial surface. At the same time she drew increasingly on geometry, which were more and more often accompanied by seemingly realistic features. Last but not least, she repeatedly created abstract geometric compositions.

A large group of pictures includes works with a painstakingly drawn motif of a tree, naturally enriched with geometric accents. “Helena Bohle Szacki‘s trees are always depicted individually, sometimes against the background of a rough rocky landscape. Some are enclosed in a rectangular frame. Placed in the middle of the page they appear even stronger in their isolation and in the surrounding void. If they are delimited by geometric figures, they seem to be deprived of breath, of their bearings,” says Katarzyna Siwerska[13], who sees a distant biographical echo in the solitude of the frequently crippled trees.

Andrzej Więckowski describes the relationship between the abstract and the figurative in a different way: “Trees, stones and mountain landscapes in these graphics do not recount their realistically conceived grace but, like triangles, circles, squares and geometric bodies, participate in the genesis of forms. They‘re not real, but ideal. They are rather ideas of trees, stones or mountain landscapes, originating from original and universal geometric forms”.[14]

[10] Conversation 1, at the specified location.

[11] Katarzyna Siwerska, Sztuka, in: Helena Bohle-Szacka. Lilka. Mosty / Die Brücken, ed. M. Różyc, Białystok 2017, pp. 85–91.

[12] Andrzej Więckowski, Graphische Traktate von Helena Bohle-Szacki, in: Helena Bohle-Szacki, exhibition catalogue, no year [Polnisches Kulturinstitut Berlin, 1994].

[13] Katarzyna Siwerska, at the specified location.

[14] Andrzej Więckowski, at the specified location.

Other critics, like the Polish painter and poet Henryk Waniek, also seem to follow a similar interpretation: “The horizontal and the vertical, the diagonal and the oval. Light and dark. Far and near. These are the main elements of her language. A quote from a landscape. A lonely tree. Fractions of a larger whole. And all this put together with a rigorous geometry, which we always think is completely artificial and man-made. Wrongly so. Geometry is also a part of nature. The world view in Helena Bohle-Szacki‘s pictures corresponds to the ideas of Plato, who explained the world through the work of hidden ideal prototypes. For philosophy is the very purpose of art.”[15]

The technique used by the artist in these pictures creates a kind of formal connection between a representational and a non-representational approach. Most of the drawings were created with the help of a sharp pencil used by architects and designers: here she tirelessly covered the white surface with tiny dots or lines. In her opinion: “Initially I wanted to express as much as possible with this modest tool. Working with a whole range of shades between black and white is like creating new colours. Added to this is the differentiation of the surface structure, which can almost replace the colour. On the other hand, this technique imposes certain restrictions, and this is the challenge”[16] This is how her distinctive hallmark was created: The changing compression of black dots produces an open space on the white paper surface, creating an interplay of different, carefully selected forms. And then it turns out that what is realistic ceases to reflect reality, while abstract features become strangely tangible.

“Something emerges from nothing. Something dotted or dashed, crossed or crisscrossed, bent or linearised, rhythmicised by repetition and encompassed by straight lines, which transforms the white emptiness into a space and into light: and the whole is transformed into a piece of cosmos”.[17] This is how the critic and writer Olav Münzberg summed up the essence of Helena Bohle-Szacki‘s art. Her images are not imitations of reality; rather they evoke entirely new, mostly abstract realities whose origins lie far from the world of human experience. Perhaps they are hunches, intuitive insights into an encrypted yet clear order of things, which ultimately also includes every individual experience.

A harmonious interplay of geometric forms is often disturbed by surprising disruptions, elements of chaotic confusion, uplifting, shifting and delimitation. However, this disturbing dynamic is balanced by the rhythm of classical image composition. It would be pointless to interpret these images and impose interpretative stories on their universal dimension. At best one can only enter into one‘s own associations, like the Berlin logotherapist Ingrid Bergmann who sees them as “ideas that have become images, connections of meaning between what one feels, experiences and dreams, poured into cosmic primordial forms of geometry”.[18]

But the viewer can find him/herself in these pictures: she stands in front of a mirror and sees herself in a space where intellect and emotions merge and something intuitively imagined can be recognized. Thus the images convey a knowledge that nothing is definitively complete, that the forms are in a constant process of arising and decaying, and also that this eternal movement, if it is accepted, can possess a rare beauty.

Helena Bohle-Szacki‘s first exhibition took place in 1974 in a small gallery in West Berlin, called Kleines Kra, after which she gladly and frequently exhibited her work all over Europe. Until 2007 she had about 40 solo exhibitions in many European cities, from Berlin, Warsaw and Paris, to London, Copenhagen, Hamburg, Lodz and Prague It was always important for her to share her work with others, to surprise and delight viewers, and to give them food for thought. Some titles, which the artist often changed and regarded as a way of helping the viewer (“Captured”, “Hidden”, “Flight”, “Beginning of the End”, “Departure”, etc.), have prompted a few people to search for an interpretative key, which might refer to the artist‘s life. It remains to be seen whether such an interpretation of Helena Bohle-Szacki‘s art can be justified. She herself rejected this. But her past was more than just a hidden borderline experience.

[15] Henryk Waniek, in: Helena Bohle-Szacka, exhibition catalogue, Płocka Galeria Sztuki, Płock 1999.

[16] Conversation 1, op. cit.

[17] Olaf Münzberg, introduction to the exhibition, Helena Bohle-Szacki, Berlin 2001.

[18] Ingrid Bergmann, Introduction to the exhibition, Helena Bohle-Szacki, Rückblicke. Zeichnungen 1973–2007, Galerie DerOrt / Miejsce, Berlin 2007.

Memories

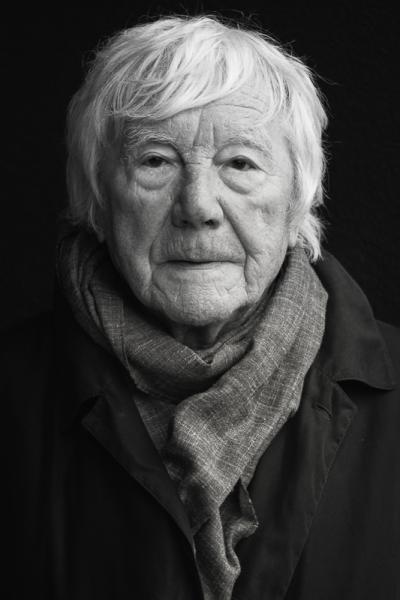

True, Helena Bohle-Szacki took part in a major survey in 2005[19], when she allowed herself to be interviewed on several occasions and appeared in public. But she never regarded her role as a victim to fundamentally shape her identity. Indeed she always kept her experiences at a distance, as well as investing them with a certain sense of humour, for she never dwelt on the horrors she had experienced. For decades she felt neither the need, nor probably had the strength, to share her dramatic experiences with the world around her. She never concealed them, but it was not a special topic, nor the focal point of her existence. This was to change gradually over the years when she consciously took on the role of a contemporary witness after the deterioration in her eyesight (a late consequence of her time in the camp) finally put a stop to her active artistic life. However, the most important reason for her to bear witness to the horrors she had experienced was her obligation to the victims who no longer lived and, at the same time, to posterity.

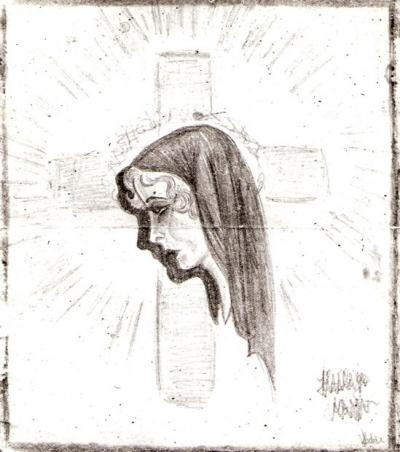

Her path in life was determined by the history of Poland and Europe in the 20th century. Born in 1928 in Polish Białystok, Helena, whose father was of German and mother of Jewish descent, experienced threats, fear and loss in wartime. Her mother was forced to live in hiding, her father daringly helped the fugitives from the Białystok ghetto, and her Jewish half-sister was arrested and murdered in the street. She herself was arrested in spring 1944, and after a few weeks in prison was transferred to the Ravensbrück concentration camp before being transported to Helmbrechts, a subcamp of the Flossenbürg concentration camp in Upper Franconia. Hunger and violence, humiliation and dehumanisation were part of everyday life in the camp world. There were not many ways to survive and resist, and these required courage and strength. Helena Bohle-Szacki found them in the form of a friendship, but also in her latent ability to draw. She began making small drawings in the small subcamp, which was set up specifically to guarantee a sufficient work force for the local armaments factory. Her images were mainly those of saints with transfigured, beautiful faces, which were intended to give comfort and hope to her oppressed fellow prisoners. (ill. 25) Personally, this was probably the initial impulse for her later work.

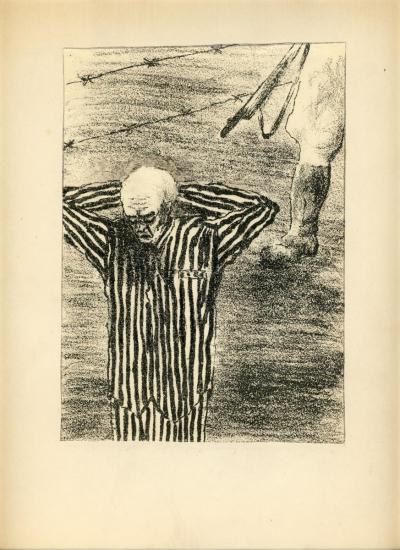

After a horrific death march at the end of the war the women were liberated and the 17-year-old Helena, emaciated and weakened, managed, not without difficulty, to return to her family in Poland. Their home in Białystok no longer existed and they were forced to rebuild their life in Lodz from scratch. Although she was afflicted by several illnesses Helena was able to start and complete her graphic studies. Only once did she address the camp world artistically: when she made some drawings to illustrate the stories of Tadeusz Borowski. (ill. 26, 27) Katarzyna Siwerska writes “The charcoal drawings on cardboard were never used, but they do have a style of their own that is clearly different from the rest of her work. Nameless, dehumanised prisoners without individual faces were contoured with a restless, vibrating line. This chaotic layering of images and memories elicits an inconceivable fear.”[20] After this one episode, for decades her experiences in the camp were no longer an issue for her – in art as well as in life.

Her late, reflective narrative aimed to bring to light the inhumanity of the National Socialist system. She said: “Today I can say that it is good to have experienced it. Everything was on the brink of life and death, but I‘m alive. I have learned a lot from that. I know for sure that it is unacceptable to put a person in extreme situations. I managed to stand firm, but I saw wonderful people collapse. That was the perfidy of the camp structure. Often people had only one choice: between viciousness and death. And then very few chose death. But they were not to blame, it was the system that destroyed people. The camp forced them to make inhuman choices.”[21]

Her recollections also shaped the feeling of being different from her very childhood onwards, since she was not a part of the Catholic majority in the student community. This feeling continued until she moved abroad. Perhaps this is precisely why she was unconditionally open to all things different and her home became a refuge for emigrants, artists and unorthodox people of all nationalities. Although she clearly felt she was a part of Polish culture, she resisted any national attributions.

A slim illustrated book “Spuren, Schatten” (Traces, Shadows), published by Helena Bohle-Szacki, constitutes a kind of bridge between memory and art in her life. The short jottings that accompany her paintings provide insight into her thoughts. She writes: “In the middle of the night I wake up bathed in sweat, terrified, my own scream wakes me, I peer into the darkness, listen to the sounds in the old house and at the same time I so much wish that the spirits would come alive again”.[22] A few pages later, we read: “How I long to reach a state of calm without having given up”[23] I presume that she achieved this state.

Helena Bohle-Szacki‘s importance cannot be reduced to one area of her work, it is based entirely on the multi-layered complexity of her life. Thus Helena, nicknamed Lilka, lives on in the memory of her fellow humans, and is to be preserved for posterity: as an extraordinary, life-affirming woman whose fate was marked by history, fashion and art. It is important to emphasise one factor that had a particularly strong influence on her personality: she had the rare talent of being able to give other people generous gifts of human warmth, friendliness, attention and, last but not least, she was always willing to help.

Ewa Czerwiakowski, May 2018

Here you can find the article on Helena Bohle-Szacki in the Atlas of Places of Remembrance.

[19] As part of the international survey led by Alexander von Plato, almost 600 interviews were conducted with former forced labourers and concentration camp prisoners from 26 countries. From this material the online archive was created, in which the interview with Helena Bohle-Szacki can also be viewed; see: https://zwangsarbeit-archiv.de/archiv

[20] Katarzyna Siwerska, at the specified location.

[21] In conversation with the author, Berlin, 31. January 1999.

[22] Helena Bohle-Szacki, Spuren, Schatten. Zeichnungen und Aufzeichnungen, Berlin 2003.

[23] Ibid.