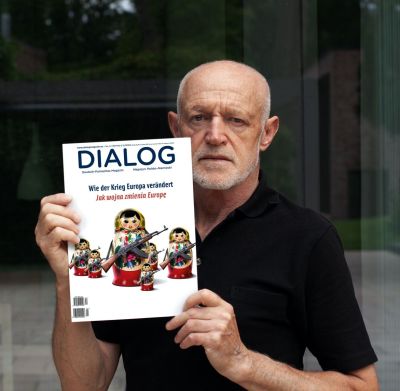

Jan de Weryha-Wysoczański

Mediathek Sorted

Jan de Weryha – Modern Abstract Art in Wood

Parallels with abstract modernism are obvious. Memories are evoked by a tour of the museum-like exhibition rooms in Hamburg-Bergedorf (the so-called de Weryha Collection), which are affiliated to the studio of the Polish-born sculptor (ill. 94-97) and which offer a representative cross-section of his work over the last two decades. When people with some knowledge of art look at de Weryha's works, they can discern tendencies in abstract modernism that go back to the second decade of the twentieth century. Above all, they are able to identify those movements and currents of abstract art in which geometry, serial structures, and a radiance of the material – whatever its manifestations – which played pivotal roles, and which still retain their significance and exert their influence over generations of artists today.

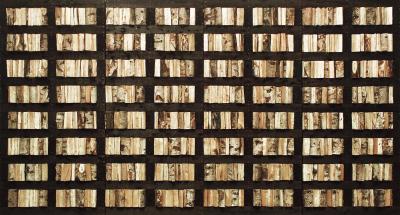

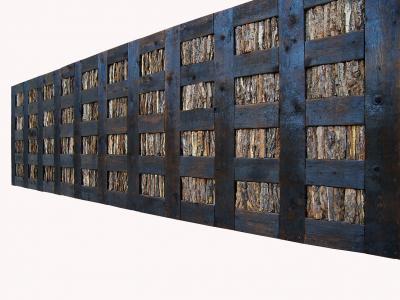

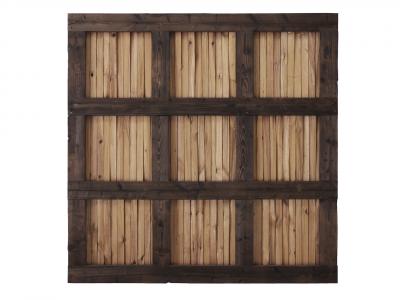

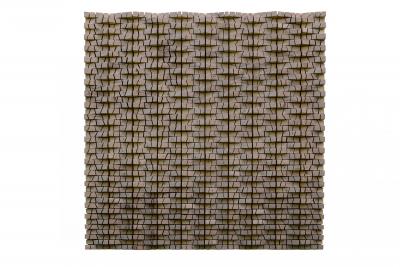

In particular, the "Wooden Panels" created by de Weryha since 2001 reveal geometric, grid-like and reticular structures that were invented in painting in the years after 1910 and were further developed in object art in the following decades. In de Weryha's work these structures can be rigorous and regular (ill. 45, 58, 91), or they can exhibit irregularities caused by the natural shape of the material, its processing or its arrangement (ill. 34, 39, 80). The Dutch artist Piet Mondrian laid the foundation for regular geometric patterns in the visual arts in Paris before the First World War, when he decided to break with the figurative forms of the Cubists Braque and Picasso and translate impressions of nature, such as the structure of a firewall or the rhythm of the sea, into grid-like rectangular patterns and short, intersecting lines in grey and white.

The group De Stijl, founded in 1917 in Leiden by Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg and Georges Vantongerloo, consistently replaced impressions of the representational world with geometric compositions in order to contrast the outwardly perceived shape of things with a pure man-made art. The aesthetic balance of different sized forms and colours in the painted pictorial surface, soon applied to interiors and architecture. Depending on the artist, this could pursue meditative dimensions, prepare egalitarian structures in society, or present art appropriate to the machine age and its anonymised work processes. Serial patterns did not yet play a role. However, non-objective, numbered picture titles became the norm. This custom has been preserved to this day in many areas of contemporary art by dispensing with work titles or always using the same designations. Nowadays, after several years of "untitled" works, De Weryha generally uses the terms "wooden object" or "wooden panel": terms that differ only in the years of origin.

The possible redundancy in the exclusive use of rectangles was addressed by De Stijl artists like Bart van der Leck and Vilmos Huszar who introduced irregular polygons and triangles. This can also be observed in de Weryha (ill. 76, 91). Their German successors like Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart, Carl Buchheister and Erich Buchholz (now known as constructivists), added new colours, serial strokes and combinations of rectangles and circles. In the 1940s Mondrian readmitted serial patterns and impressions from the environment, for example from music. Just as he once led the viewer rhythmically through the picture along lines and serial squares to prominent rectangular shapes, de Weryha now guides the viewer along a comparatively regular grid through rhythmic distributions to ever new formal experiences across the surface of his objects (ill. 34). Anyone who wants, can also find in de Weryha's work the original form of the abstract geometric design, the "Black Square" (1913/15) by Kasimir Malewitsch, albeit with altered dimensions and in modified colours (ill. 68, 70). The monochrome square, which Malevich called the "sensation of non-objectivity", enables de Weryha to concentrate entirely on the optical and haptic quality of his material. Indeed, wood as a material in different colours and shapes and wood-like scraps of plant like bark and reed play a decisive role in his work. Through the use of geometric arrangement, de Weryha liberates the material from its natural contexts and transforms it into an objectified form.

The De Stijl group and early constructivists were not yet interested in material phenomena. In Germany people only discussed and propagated the appropriate use of natural materials in industrial modernism in connection with the applied arts (i.e. arts and crafts), from the Deutscher Werkbund, founded in 1907. In Western Europe object art only developed in a slow process, moving from the invention of collage as an artistic technique by DADA artists around 1916, via the "MERZ pictures" by Kurt Schwitters, to his object and spatial collages, like the walk-through "Merzbau", created in 1923. That said, constructivist sculpture, in which the material played a new role, had evolved much earlier in Moscow. Beginning in 1914, Vladimir Tatlin still in close connection with Futurism and Suprematism, developed three-dimensional "corners" and "counter-reliefs" made of found materials like wood, iron, zinc, leather and metal wires, thereby propagating a "culture of the material".

Under the influence of the Russian Revolution, Alexander Rodchenko and El Lissitzky developed geometrically determined, constructivist objects that were intended to be "non-objective in a material world". Emigrants from Moscow like Naum Gabo and his brother Antoine Pevsner exported these ideas to Berlin and Paris, and Katarzyna Kobro exported them to Warsaw, where she emigrated in 1922. As the equivalent of the modern world they introduced into sculpture smooth, industrially manufactured and shaped materials like Plexiglas, sheet steel, industrially processed glass and wood in geometric forms and pure colours. Starting in 1919, the Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar and Dessau not only offered a discussion and teaching platform for all previous and current branches of constructivism, but also propagated its application in all areas of life. To this day, its resonance has shaped broad areas of art theory and our everyday lives.

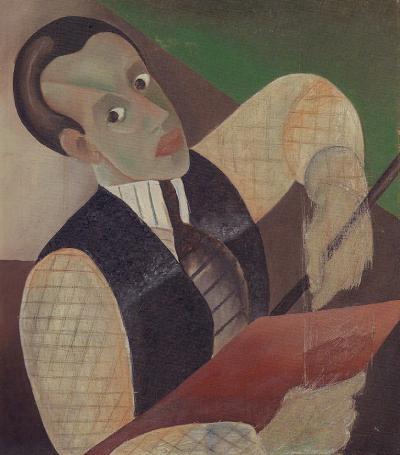

In Poland (after the first Constructivist works by Henryk Stażewski and the founding of the Blok group in 1924 by Stażewski, Henryk Berlewi and Władysław Strzemiński, who had been married to Kobro since 1920), an independent tradition of Constructivism emerged. Although it reflected the entire European movement, it was hardly noticed by the West. It was followed in the 1960s and 1970s by a "neo-avant-garde" connected to Constructivism. The artists included Edward Krasiński in object art, Zofia Artymowska and Jerzy Grabowski in graphic art, and Józef Robakowski and Ryszard Waśko in painting, film, video, and object art. Today, young Polish artists such as Natalia Stachon and Marlena Kudlicka, some of whom work in Germany, once again refer back to the first generation of the Constructivist Polish avant-garde.

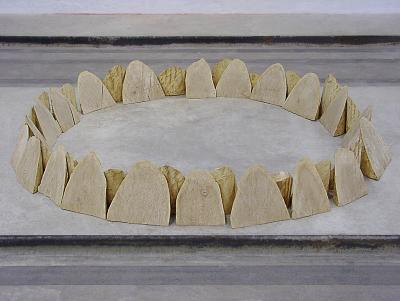

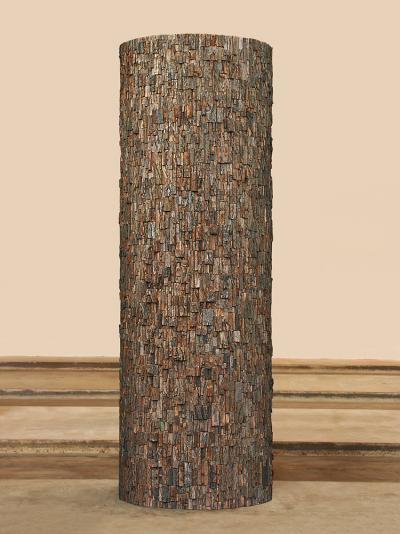

De Weryha initially applied geometric forms to the arrangement of his floor works (ill. 14, 16, 26, 29), then to free-standing objects like the "Wooden Pillar" (ill. 38), the "Wooden Cube" (ill. 40) and the cone-shaped "Wooden Object" (ill. 93), and finally to the internal structure of his "Wooden Panels" (ill. 78, 91, 92). But these rigorous, regular works also point back to Concrete Art, which followed Constructivism. Introduced by van Doesburg and followed up by the 'Art concret' group founded in Paris in 1929, this movement with the Swiss Max Bill and Richard Paul Lohse was given its theoretical basis in 1936 and the 1940s, a basis that is still valid today. While Bill initially only allowed strict mathematical and geometric systems as the basis for "subjective forms" in art, in the 1960s he also allowed statistically calculated, uniform distributions, regular grids and "orders". Starting in 1940, Lohse researched "serial" and "modular orders", which he propagated in the 1980s.[1]

[1] Richard Paul Lohse: Modulare Ordnungen (1985), Serielle Ordnungen (1985), in: Richard Paul Lohse 1902-1988, exhibition catalog Wilhelm-Hack-Museum, Ludwigshafen 1992, p. 18 f., 21 f.

Regular grids and orders consisting of serially arranged modules can still be observed today in the "Wooden Panels" by de Weryha (ill.78, 91, 92). However, his compositions are not based on a sophisticated mathematical system, but on simple measurements and working with proportions derived from experience, also oriented on the possibilities of the modular components obtained from the wood.[2] Eugen Gomringer, Bill's secretary and the inventor of Concrete Poetry, has pointed out that since the 1990s various artists have added further "fields" to the initially rigorous system of Concrete Art. These can be traced back to broadened perspectives, new perceptions and experiences with other materials.[3] De Weryha plays a role in this traditional thread, by concentrating on wood as a material, and optimising the perception of the material on the basis of concrete structures.

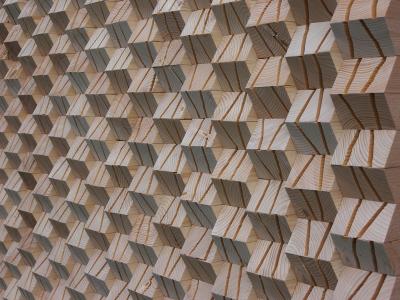

De Weryha's reliefs and objects, whose appearance is characterised by a largely monochrome geometric surface structure, also draw on the experiences and insights of the ZERO group, founded in 1957 by Otto Piene and Heinz Mack, and shortly afterwards joined by Günther Uecker. The group cooperated with other international artists' associations like the Dutch group Nul (English: Null) around Jan Schoonhoven. ZERO was not a direct reflexive reaction to Constructivism and Concrete Art, but it nevertheless acted with the background knowledge of the insights acquired there. Piene's serial hole patterns and the objects and installations developed from them, as well as Mack's geometrically structured and rotating, often circular aluminium reliefs, served to make light visible in circular, spiral, field and wave movements. These were followed by Uecker's nail pictures and objects coated with white paint and Schoonhoven's stereometrically structured white reliefs made of cardboard. In Poland, Jerzy Jarnuszkiewicz constructed freestanding metal sculptures in the mid-1960s featuring geometrically arranged grids, bars, and lamellas, with which he investigated problems of space in relation to light and rhythmic movements. Since 1968 Jerzy Grabowski has worked in graphic art with pure white geometric embossed prints reminiscent of blind embossings by Uecker, Schoonhoven and the Bauhaus teacher Anni Albers.

Similar structures and light effects can be found in de Weryha's "Wooden Panels" (ill. 71, 79, 92) and the round "Wooden Objects" (ill. 82, 85), which occasionally change to white. Whoever wants to, will even see successors of Uecker's nail pictures in individual works (ill. 68, 77), whereby for de Weryha the focus is on the optical and haptic qualities and effects of wood as a material. In 1959 Piene introduced the use of fire as an artistic technique with his "Rauch" and "Feuerbilder". De Weryha, initiated by the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, continued along this path by charring wood to create individual objects in two colours (ill. 28, 32, 33, 35, 43-47, 59, 62, 66, 70). Here too he was not primarily concerned with colour contrast, but with adding a further expression to the material wood, obtained by means of a natural process.[4]

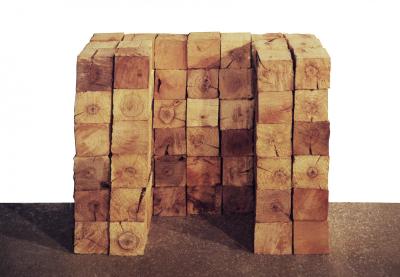

De Weryha has told interpreters of his work that he is particularly fascinated by the Minimal Art movement that emerged in New York in 1960 with the protagonists Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt.[5] Indeed, his early objects and floor works, all "untitled" (ill. 3, 10, 14, 19), consisting of wooden parallelepipeds, are in fact reminiscent of the objects by Carl Andre, who also worked with rows of metal plates, bricks, concrete blocks and wires. Minimal Artists used industrially manufactured, standardised materials like anodised aluminum, stainless steel, plexi and fibreglass, styrofoam, copper and zinc, as well as machine-made wooden workpieces that anyone might have purchased in the building materials trade as elements for their own artistic productions. They were concerned with the perception of differentiated structures in space and the effect of object and space on the viewer. De Weryha's works, however, show clear traces of handcrafted processing with a chainsaw, axe or chisel. In his work, no edge of the individual modules is straight; industrially produced materials are alien to him. Rather, his individual artistic treatment of the material wood with its optical, haptic and olfactory qualities gives it a new validity.

[2] De Weryha in conversation with the author in March 2018

[3] The occasion for Gomringer's analysis was the work of the Kiel-based graphic artist and object artist Ulrich Behl (b. 1939), who creates concrete objects made of paper and, more recently, of plexiglass. Eugen Gomringer: Die Prozesse der Wahrnehmung neu optimieren, in: Ulrich Behl. Modulare Ordnungen, exhibition catalog Museum Ostdeutsche Galerie, Regensburg 1997, p. 10 f.

[4] Polish authors have not yet seen de Weryha's congruences with the ZERO group. Galerie Kellermann in Düsseldorf, representing the artist, showed him in 2016 in an exhibition titled Zero 2.0 together with Piene, Mack and Uecker, and leads him as ZERO-artist of the second generation.

[5] Well first mentioned and discussed in detail by Rafał de Weryha-Wysoczański, art historian and son of the artist, in his opening speech to the exhibition Jan de Weryha – Objekte, Galerie Kunst im Licht 1998 in Hamburg; PDF excerpt available on the website of the artist.

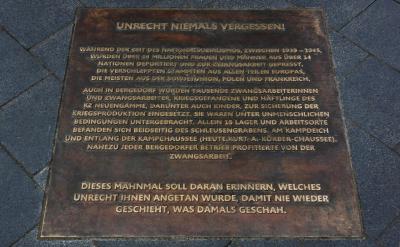

But even in this case, individual strands of tradition retain their significance. While the Americans derived Minimal Art from, amongst others, Constantin Brâncuși's "Endless Pillar" and thus from Constructivism, Europeans see it in the tradition of Concrete Art. In any case, the transitions are fluid: Max Bill's "Gates" and "Pavilions" derived from Concrete Art and made of layered granite blocks since the 1980s could just as easily be assigned to Minimal Art. The same applies to the memorial that de Weryha erected in 2012 in memory of the forced labourers during the Nazi regime who worked in the Bergedorf district of Hamburg (ill.72a). The cuboid concrete pedestal objectifies commemoration in the form of a minimalist, geometric form lacking any narrative character. In this way it is similar to the "Black Form" erected by Sol LeWitt in Hamburg in 1987, a horizontal black cuboid made of aerated concrete blocks and dedicated to the memory of the Jewish community in Hamburg-Altona who were annihilated by the National Socialists. De Weryha, however, added an interactive element to his monument that conflicts with the classification of Minimal Art: a viewing slit containing a facetted stainless steel cylinder that often breaks the view of the environment behind it. He thereby symbolised the restricted view of the forced labourers held captive under inhuman conditions and added a level of experience to the objective remembrance (ill. 72b).

The intensification of the senses, the sharpening of sensibilities for the phenomena inherent in the material that is decisive for de Weryha, has been observed in Post Minimal Art artists since the late 1960s. Richard Serra, for example, hurled liquid lead into the corners of rooms in order to make the transformation and presence of the material in the physical process visible by means of the solidified blocks. Similarly, de Weryha places and layers split pieces of wood, branches, and bark in corners, along walls, and around pillars (ill. 7, 54, 55, 65). This dynamic form makes it possible for us to experience the working process and appreciate the natural product with every single carefully placed part. Following the example of Barry Flanagan, (one thinks of his "Four Rahsb" and "Four Casb" filled with sand), de Weryha designed conical amorphous monoliths, which he cut out of wood (ill. 1, 12, 20, 21). Like Ulrich Rückriem, who worked with dolomite and granite blocks, de Weryha sawed his forms apart and reassembled them flush.

Rückriem, one of de Weryha's most admired sculptors,[6] exposed the inner structure of the stone with simple, but logically and systematically tested procedures like drilling, fracturing, sawing and splitting. De Weryha claims that his work is similarly based on “three pillars: cutting, breaking and splitting. Terms like rhythms, tensions, dimensions, density and structure are constantly present.”[7] But there are still fundamental differences. While Rückriem moved the split and broken individual parts so closely together that the mass of the stone could still be experienced, de Weryha has concentrated on the many different processes involved in working with wood. With broken edges he creates dramatically moving surfaces (ill. 69, 80, 90) and internal structures (ill. 82, 84, 87-89) and exemplifies the behaviour of the material by breaking and splitting it in each individual module. In his most recent "Wooden Panels", he moves the clefts so far apart that graphic structures are created and insights into the inner structure of the modules are possible (ill. 75, 78, 79, 91, 92). "In my wooden objects," says de Weryha, "there are no stories, no interpretations can be applied to them. They are clean and clear, it is only about the materiality of the wood".[8]

In Poland, the use of wood and other natural materials in modern sculpture and object art has its own tradition. From 1960 onwards, the National High School of Artistic Techniques in Zakopane (Państwowego Liceum Technik Plastycznych w Zakopanem), rediscovered and passed on traditions from folk art. On this basis, Antoni Rząsa, Stanisław Kulon and Józef Kandefer created wooden figurative sculptures that took up expressionist or cubist tendencies once again. Adam Smolana, de Weryha's teacher, abstracted body forms and, like Henry Moore, assembled them into larger masses. Władysław Hasior, also a student in Zakopane, worked with found objects made of wood and created surrealistic compositions from them. Since 1960, Jerzy Bereś, who trained in Krakow, has designed objects made of raw hewn wood, jute ropes, stones, leather, and cloth reminiscent of primitive peasant artefacts and which conjure up ethnological traditions and archaic myths.

[6] Jan de Weryha in an interview „Offenbarungen in Holz“ with Mariusz Knorowski 2006 (exhibition catalog Jan de Weryha-Wysoczański. Objawienia w drewnie, Orońsko 2006, p. 6/10); extracts available online http://www.kultura-extra.de, third last paragraph

[7] online-interview with Helga König, 2015, http://interviews-mit-autoren.blogspot.de/2015/03/helga-konig-im-gesprach-mit-dem.html

[8] ibid

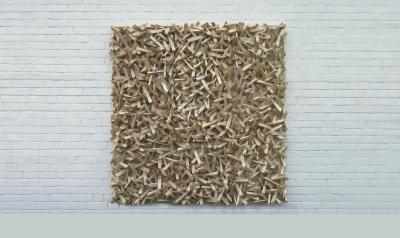

Other Polish sculptors deliberately turned away from "precious" materials and pursued non-representational tendencies. They regularly took part in symposia and exhibitions in Western countries. Jarnuszkiewicz developed expansive abstract sculptures from welded metal sheets. Magdalena Abakanowicz, who had actually studied painting, found new abstract forms in textile art by weaving a "rough" material, sisal, as used for ship ropes, into room-filling tapestries hanging freely from the ceiling, the "Abakans," for which she was awarded the Grand Prix at the 1965 Sao Paulo Biennale. The Polish academies also initiated a renewal of textile art. There they created three-dimensional wall reliefs and room-filling environments that occupied areas of sculpture. The surfaces of these abstract, freely designed works transferred the 'all-over' of Jackson Pollock's painting and European Informality into structures made of natural material. Similarly rough-structured reliefs can recently be found in de Weryha's work. These range all the way to the wall-filling format, where he dissolves the underlying geometric grids into an 'all-over' of fragments placed close to one another (ill. 37, 39, 42, 52, 80, 90).

Wood, which is widely known in Central Europe to have been used in figurative sculpture for well over a thousand years, only becomes a "base" or "poor" material when it finds its way into art as a find from nature or everyday life. In the early 1960s, leading artists of the Italian art movement 'Arte povera' began working with found materials from nature, but also with every conceivable material from everyday life. They showed that even "poor" materials can be charged with myths, stories, metaphors, and symbols, thereby opposing the traditional hierarchy of materials, mass consumption and even plain Minimal Art. From the very start Mario Merz worked with bundles of brushwood, which he arranged in groups along the wall, laid out on the ground, or from which he constructed his well-known "igloos". But he also used many other materials. Giuseppe Penone still uses tree trunks directly obtained from nature for his installations, the natural form of which remains visible even after extensive artistic interventions.

In de Weryha's work, the vertically and horizontally layered works, in which the wood is only roughly segmented to reveal its natural beauty and variety (ill. 3, 9, 17, 24), the ground works of branches and bark (ill. 54, 55, 65) and the "wooden object" of layered birch branches and veins (ill.57) have the closest connection to 'Arte povera'. It is hardly necessary to emphasize that de Weryha does not perceive wood as a "poor" material, but rather celebrates its richness in forms, colours and structures. Similar to the 'Arte povera' artists, who emphasized the high narrative and emotional value of the materials they used, he also points to their culturally critical, social aspect. He is keen that his work with wood, which plays an important role as a catalyst in the cycle of nature, "in a society that regrettably is only oriented towards consumption and above all profit, will at least make people stop and think for a short moment".[9]

In view of his circular and partly conically layered floor works of wood or bark segments (ill. 16, 22, 23, 25, 26, 29), past authors, who could not yet know the current range of de Weryha's works, referred to impulses from Land Art, above all from Richard Long and Robert Smithson.[10] Likewise at the end of the 1960s, American artists transferred colossal forms of Minimal Art to the deserts and mountains of North America. They marked traces of their wanderings, redesigned gorges, dunes, and watercourses with construction machines, and created stone settings in the form of circles and spirals. One of these was Smithson's "Spiral Jetty" (1970), which was reminiscent of prehistoric places of worship. These artists also set up an alternative to the industrial consumer world by working in and with nature, uncovering the history of the earth and exposing their works to renewed corrosion. But here lies the decisive difference to de Weryha: his works are basically conceived for interior spaces and only in a few cases (and then temporarily) are meant to take place outside (ill. 60, 61). Due to their size, however, some of his ground works could only be exhibited by moving them elsewhere. Two such examples were "Orońsko" 2006 (ill. 53) and "Chilehaus" 2011 (ill. 67). On the other hand, Richard Long has also conceived circular wall tableaus of meditative circles of stones, peat, driftwood, branches, firewood and river mud, for museums and exhibition spaces in order to make them accessible to a larger public. The connection between de Weryha and Land Art is not only formal, but above all a love of the world and nature.

[9] ibid

[10] Jan Stanisław Wojciechowski 2005, p. 5/9 (see further reading; text available online on the website of the artist, polish, page 2/english, page 2); Dorota Grubba 2006, p. 4112/4115 (see further reading; text available online on the website of the artist). Maryla Popowicz-Bereś referred in her 2014 master's thesis (see further reading) even Richard Long as the main source of inspiration for de Weryha, p. 43 (text available online on the website of the artis; german translation ibid, p. 39)

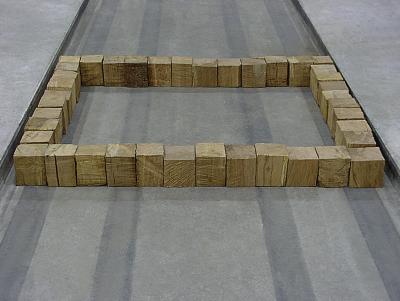

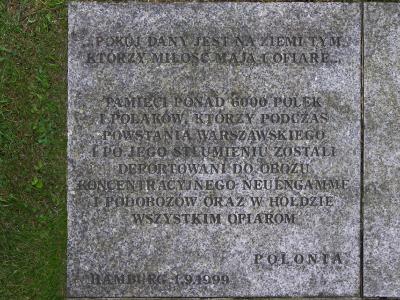

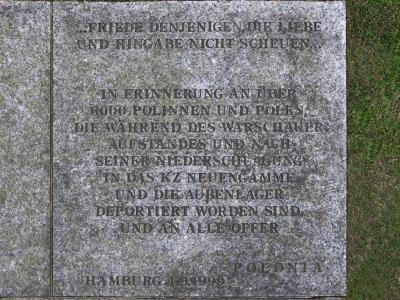

In 1999 De Weryha completed a memorial "In Memory of the Deportees of the Warsaw Uprising 1944" for the Neuengamme concentration camp memorial (ill. 18a-c), which consists of thirty roughly hewn granite blocks placed in a row on a surface of polished slabs. Although it looks like a freely conceived Land Art work, it is in reality Monument Art. Symbolically, the individual stone blocks allude to the "diversity and distinctiveness" of human individuals, but their regular arrangement points to the "totalitarian, perfectly organized apparatus" of National Socialist tyranny. The footpath to the memorial, lined with granite gravel, embodies the path "that those condemned to death were forced to follow".[11] At best the material in this work is reminiscent of Rückriem. More significant, however, is the fact that in Poland, unlike other socialist countries, abstract Monument Art was already being practiced in the mid-1960s at a similarly troubled location. In 1964 Franciszek Duszenko, Adam Haupt and Franciszek Strynkiewicz erected a field of three thousand irregularly split stone blocks for a Memorial in honour of the victims of the Treblinka extermination camp. The field was intended to evoke thoughts of a "duration [of remembrance] beyond time" and "make tangible the tragic presence of people walking to their death".[12]

On the occasion of a solo exhibition by de Weryha at the Galeria Szyb Wilson/Shaft Wilson Gallery in Katowice in 2005, Jan Stanisław Wojciechowski, a sculptor and professor of cultural anthropology in Warsaw, pointed out that in the 1970s when de Weryha was a student in Poland, international modern art was aready being widely acknowledged by academies and galleries. Young artists in particular had made no bones about adapting the various tendencies of contemporary art to their own needs. They exploited the best examples of conceptual art, minimal art, performance, and new media and enriched them with personal motifs, integrating them into other political or anthropological contexts, and turning to new materials or to nature: “Jan de Weryha-Wysoczański left Poland with a baggage of European intellectual and artistic values”.[13]

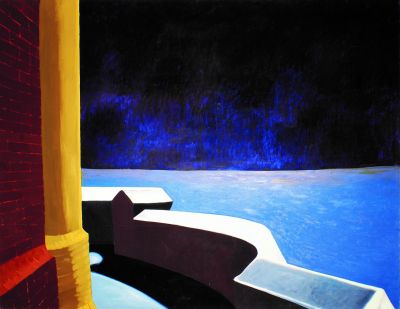

On the occasion of the exhibition in Katowice, which took place in the engine room of a disused colliery, Wojciechowski suspected that de Weryha's art would take up a "romantic position" by deliberately opposing his insights into nature to the technical world or to "late Modernism, i.e. the world of globalisation, accelerated consumption and algorithms".[14] This in turn places the artist in a relationship with Installation Art, which traditionally reacts to found or deliberately selected spaces. In her master's thesis written in 2011 at the University of Technology in Radom (Politechnika Radomska in Kazimierza Pułaskiego), Aleksandra Warchoł also notes that de Weryha creates "arrangements in space" in addition to his wooden objects.[15]

Although the engine house in Katowice served only as an exhibition space for the artist, other arguments can also be found for the fact that he consciously reacts to specific spaces with individual installations. For example, he has integrated block-like and round wooden segments into doorways or wall niches (ill. 3, 9, 48), deliberately aligned ground works with the architecture (ill. 6, 17, 59), or integrated them into architectural elements (ill. 8, 14). The above-mentioned "wooden objects" in corners, along walls or around pillars (ill. 7, 54, 55, 65) and the "untitled" works (ill. 11, 30) stacked or grouped on wall sections may also be included here. As ephemeral on site installations that refer specifically to architecture are the cruciform floor work of short birch trunks for the exhibition entitled Objawienia w drewnie (Revelations in Wood) in 2006 at the Centre for Polish Sculpture in Orońsko (Centrum Rzeźby Polskiej w Orońsku)(ill. 53), and on the occasion of Hamburg Art Week 2011, his ground work entitled "Chilehaus five lines, which consisted of laid birch trunk segments that snaked in five parallel lines through rooms in the Hamburg Chilehaus" (ill. 67). The artist called it a "temporary spatial experience".

[11] De Weryha in an online-interview with Helga König, 2015, http://interviews-mit-autoren.blogspot.de/2015/03/helga-konig-im-gesprach-mit-dem.html

[12] Wojciech Skrodzki, in: Andrzej Osęka/Wojciech Skrodzki: Polnische Bildhauerkunst der Gegenwart, Warschau 1977 (german), p. 33

[13] Jan Stanisław Wojciechowski 2005, p. 4/8 (see further reading; text available online on the website of the artist, polish, page 1/english, page 1)

[14] ibid, page 7/11 (online polish, page 4/english, page 4)

[15] Aleksandra Warchoł 2011, page 10 (see further reading; available online on the website of the artist, german translation, page 10)

Connections have even been made between de Weryha's works and Action Art and happenings in the 1970s.[16] In 1968 the Polish sculptor Jerzy Bereś began performing as an action artist, using his ethnographically inspired wooden assemblages and Dadaistic-looking vehicles in ritual happenings and performances, and adapting finds from nature in artistic actions that protested against the destruction of the natural world. Decades later, these found objects could still be seen as individual objects in exhibitions. Tadeusz Kantor had been working in the theatre since 1961 with "poor" and "scanty" props as the carriers of true-to-life objectivity. What remained of his stage performances and happenings were assemblages like his group of works "Emballages"; and objects from Edward Krasiński's Happenings that appeared constructivist, were charged with meanings and intended to "release energies". These objects also later found their way into exhibitions, collections, and museums, as did numerous objects by Joseph Beuys, which were removed after his actions and thus became autonomous works of art. Although De Weryha has not organised any actions, happenings or performances as the results of ongoing artistic processes, his elaborately placed and detailed ground works have an impact, not least due to the rough character of the material and the use of finds from nature.

Wojciechowski was probably the first to point out that de Weryha arranged the wood in some of his wall objects like books, thus creating "powerful, mysterious libraries" (ill. 32, 35, 45, 46).[17] In the same year an exhibition which presented ground works and free-standing objects in the Patio Art Gallery/Patio Galeria Sztuki in Łódź, was also entitled Drewno-archiwum (English: Wood Archive), an exhibition in 2009 in the Municipal Gallery in Gdansk/Gdańska Galeria Miejska was entitled “Tabularium”, a term that in Roman times referred to rooms and buildings used for storing documents and archival records. As Urszula Usakowska-Wolff wrote in the catalogue of the exhibition in Łódź, on closer inspection some of the "Wooden Panels" resembled 18th century wooden libraries, xylotheques. Other works, which consisted of thousands of pieces of wood, perhaps centuries old, were a "unique archive of timeless time".[18] Grażyna Tomaszewska-Sobko wrote about de Weryha's exhibition in Gdansk that de Weryha's work was "an attempt to archive material coming from the world of nature". Katarzyna Rogacka-Michels remarked that "he creates the impression of a morphology of wood or of a wood archive".[19]

These connotations to the work of de Weryha also have a counterpart in 20th century art. In the aftermath of Post Minimal Art and Arte Povera, in the 1970s artists began to collect traces and relics of private and social expressions of life. Nikolaus Lang collected found objects belonging to people who had died; Christian Boltanski collected remnants from his childhood; and Raffael Rheinsberg collected legacies from industrial work processes. Such activities resulted in "archives" and "inventories" in the form of ground works, in cupboards and shelves. Boltanski even created fictitious archives from inscribed empty metal boxes representing people's fates and intended to preserve their memory. That said, De Weryha has neither systematically collected wood nor presented the materials he used didactically or in rows. His artistic preoccupations focus on exploring the origins of the material, "grasping its structure and core". By means of simple interventions, he tries to influence it in such a way that it retains its identity and, as he himself says, celebrates the "Archaic in wood".[20] Decades of work have resulted in something like an "archive" (more like a museum collection of his works), which then logically provides information about the material's manifestations and the artist's working steps.

Looking back on the past two decades of his work one can see that not only the concept of the "archive", but also the aforementioned connections of his works to preceding modernist art styles are only temporarily suitable as a model for interpreting his works. De Weryha uses the multi-branched Polish, German, and international strands of Modernism to extract those tendencies that enable him to present the material he uses, wood, in an object-like manner. This enables him to add new artistic impulses to these styles and movements, some of which are historical and others still living, and use them in his preferred material.

[16] Maryla Popowicz-Bereś, master's thesis 2014, page 53 (see further reading; available online on the website of the artist, german translation, page 48)

[17] Jan Stanisław Wojciechowski 2005, p. 5/9 (see further reading; text available online on the website of the artist, polish, page 2/english, page 2)

[18] Urszula Usakowska-Wolff 2005, last paragraph (see further reading; catalog available in polish/english on the website of the artist)

[19] exhibition catalog Tabularium 2009, page 7, 11/13 (see further reading; text of Grażyna Tomaszewska-Sobko available on the website of the artist, polish, german; text of Katarzyna Rogacka-Michels ibid, polish, german, page 5)

[20] De Weryha in an online-interview with Helga König, 2015, http://interviews-mit-autoren.blogspot.de/2015/03/helga-konig-im-gesprach-mit-dem.html

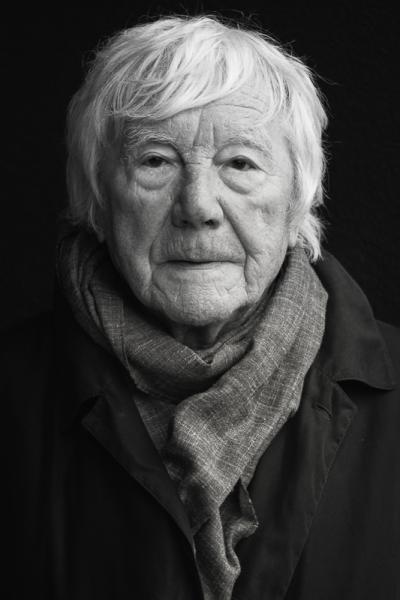

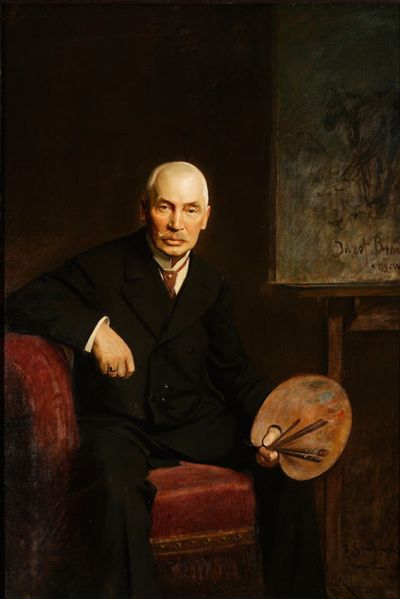

JJan de Weryha-Wysoczański was born in 1950 in Gdańsk/Danzig. His father came from a Galician aristocratic family and his mother had German ancestors. Both of his parents came from Lemberg.[21] After graduating from high school, in order to bridge a four-year waiting period for a place at university he took an apprenticeship in sculpture workshops in Gdansk. In 1971, after an intervention from the Ministry of Culture, he was awarded a place at the Sculpture Department of the State Academy of Fine Arts in Gdansk/Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Sztuk Plastycznych w Gdańsku (PWSSP), today's Academy of Fine Arts/Akademia Sztuk Pięknych w Gdańsku. There he studied until 1976, first in Alfred Wiśniewski's sculpture class, and later in the class for sculpture in architecture under Adam Smolana, one of the most important professors in his field, with whom Magdalena Abakanowicz had also studied. In the early 1950s both professors were entrusted with restoring historical sculptures in Gdansk, and worked in the fields of monument sculpture, spatial and architectural sculpture, ceramics and the art of medal-making. After graduating, De Weryha worked as a freelancer, creating statuettes, reliefs and medals in bronze and ceramics. Until 1981 he was involved in the restoration of historic architectural sculptures on the houses that had been damaged during the Second World War.[22]

Successful in his professional life, de Weryha left Poland for Hamburg in 1981 for political reasons before the declaration of martial law, along with his wife Maryla, who had studied Polish philology, and his son Rafał. There he initially worked with drawings before turning to painting, small sculptural forms and medals in bronze, copper, wax and polyester. In 1996 he began to work figuratively and abstractly in wood, sometimes in large formats. Whilst he was working with large blocks of wood with a chainsaw and the tools of the trade, he said that he noticed the beauty and abstract quality of the raw material. Traces of these early experiments can still be found in the works made in 1997 (ill. 1-5). Active in Hamburg's cultural scene from the very beginning, he opened a studio in 1998 in a hall in the former Bundesbahn repair works in Hamburg-Harburg, an industrial building erected in 1883 and abandoned in 1990 and made available to him by the Hamburg cultural authorities.[23]

In 1999 this was followed by his design for a memorial in the Neuengamme concentration camp memorial site (ill. 18a-c), which commemorates more than six thousand Poles who had been deported to the camp after the Warsaw Uprising was suppressed in 1944. The memorial was inspired by the Hamburg branch of the Bund der Polen in Deutschland e.V., designed by the artist in an honorary capacity and financed by donations. Under the patronage of the Polish Consulate General and the Polish Catholic Mission it was inaugurated sixty years after the German invasion of Poland and the beginning of the Second World War by Hamburg's cultural senator Christiana Weiss in the presence of the Polish writer Andrzej Szczypiorski. In 2000 de Weryha exhibited his wooden objects for the first time. The exhibition was also opened by Christina Weiss as part of a series of events in Hamburg featuring culture from Poland. From 1998 to 2005, he created works placed on the ground and integrated into architecture (ill. 9-30, 38, 40, 41, 47-49) in his Harburg studio; and in 2001 he began making his "wooden panels" hanging on walls. (ill. 31-37, 39, 42-46).

In 2003 de Weryha wrote the following about the last group of works he had created: " In recent years my artistic deliberations have concentrated on researching wood as a material, and on understanding its structure and its core. This has led to the highest possible artistic state based on the celebration of the archaic nature inherent in wood. Here everything begins with the question of which technical means of material processing are available to the artist, and also to what extent. [...] I begin intuitively with the following question: To what extent can my intervention influence the material without depriving it of its identity? In practice, this works by introducing strict rules that the artist has to establish in his empirical engagement with nature. Certain rhythms then emerge, and also a certain monotony. I thematize these two phenomena in a continuous accentuation with a surprisingly vibrant equilibrium. At the same time I introduce a certain geometry, full of objective expressions that have impressed me in Minimal Art. On the other hand I am interested in the individual unrepeatable weave of artificially created, but natural looking wooden surfaces, which leave barely recognisable traces of interference by tools. This constant give and take between nature and the artist becomes a highly sublime and thoughtful process of mutual exchange. In turn this becomes the basis of my actions and opens up completely new solutions to me in surprising ways. [...] Some of the wooden panels, up to ten square metres in size, are huge and resemble reliefs, breathe archaically and have a monumental effect, testifying to strength and sublimity. These new wall works stand out principally on the grounds of their strongly developed architectural order and powerfully charged wooden structures, which are connected in specific rhythms. This singular constellation, which opens up unexpected forms of expression, allows me to define anew wood as a material".[24]

[21] detailed biography at Maryla Popowicz-Bereś 2014, p. 5 ff. (see note 16)

[22] illustrations on the website of the artist

[23] former Federal Railroad Repair Works in Hamburg-Harburg, Schlachthofstraße 1-3, http://www.hamburg.de/flaechenrecycling/142834/bundesbahn-ausbesserungswerk/; historical photographs of the studio on the website of the artist; Bianca Fischer: Jan de Weryha-Wysoczański: Alles Holz - Eine Hommage an Mutter Natur, in: Harburger Anzeigen und Nachrichten, 22. August 2002, text available online: http://www.kultura-extra.de/kunst/portrait/jan_de_weryha_a.html

[24] Jan de Weryha-Wysoczański: Ein paar Worte über meine neuesten Arbeiten „Hölzerne Tafeln“, 2003; available online at http://www.kultura-extra.de/kunst/portrait/jan_de_weryha_a.html

At the end of 2005, de Weryha was forced to give up his Harburg studio because the city of Hamburg had new plans for the historic buildings. At the beginning of the year he therefore decided to send his collection of works, which had grown to over fifty objects, to Poland, where he had received numerous invitations to exhibit. After 24 years absence as an artist he was able to present extensive solo exhibitions in the Patio Art Gallery (Patio Galeria Sztuki) in Łódź, in the Galeria Szyb Wilson/Shaft Wilson Gallery in Katowice and in 2006 in the Centrum Rzeźby Polskiej w Orońsku/Centre for Polish Sculpture in Orońsko, for each of which catalogues were published. They were followed by a solo exhibition at the municipal Galeria BWA (Biuro wystaw artystycznych) in Jelenia Góra and a presentation of numerous works at the XVth International Sculpture Triennial in Poznań. These exhibitions were so successful that in 2008, 2011 and 2014 three master's theses on the artist and his work were written at the art faculties in Rzeszów and Radom, all of which made close reference to the public presentations.

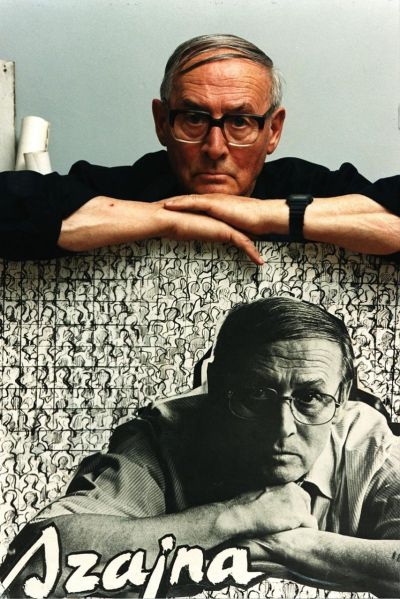

Meanwhile de Weryha had received an offer from the public authorities in Hamburg to take over the former warehouse of a museum in the Bergedorf district of the city, where the artist and his family had lived since their move from Poland. At the beginning of 2007 he opened his gallery cum studio in the four hundred square metre two-storey building, both as a working area and somewhere to display his works on a permanent basis. Until 2008 he presented around seventy works there under the title 'Holz-Archiv'; and between 2009 and 2012 he presented the collection that was shown in 2009 under the title 'Tabularium' in the Municipal Gallery in Gdansk (Gdańska Galeria Miejska). In 2012 he was commissioned by the Hamburg district of Bergedorf to create the memorial at Bergedorf's Schleusengraben (lit: sluice ditch), which commemorates the thousands of forced labourers from all parts of Europe who had been employed by the National Socialists in industrial enterprises to ensure wartime production in Bergedorf and the surrounding area (ill. 72a-c). A permanent exhibition, the de Weryha Collection, has been on view in the gallery studio since 2013. To date the collection has grown to over 230 works. The museum rooms (ill.94-97) are regularly open to the public. A supporting association, the Freundeskreis de Weryha Sammlung e.V., organises Land Art workshops and artistic trips with the artist, is responsible for concerts in the Collection and looks after its long-term preservation.[25] Since 1988 the artist has participated in numerous group exhibitions in Germany and Poland, as well as showing his works in the USA, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Belgium and England.

In 2005 Wojciechowski also identified an ecological component in de Weryha's work. His objects are "not conceptual figures, not purely conceptual statements"; geometry plays a "serving role [...] thanks to which 'nature' can express itself more clearly. And perhaps they are a way to encourage 'nature' to speak and to reveal its own characteristics, which are invisible in the conventional sense".[26] In an interview with Mariusz Knorowski in 2006, de Weryha added: "There was a good reason for me to choose wood as the material for my work. It is a product of nature that begins a new life, so to speak, after its physical death. It has a smell and changes colour, it swells and dries out. The power of this material dominated my thoughts completely and has inspired me to remain faithful to it, despite the seemingly more topical multimedia techniques that are available today".[27]

Twelve years later, in 2018, the diversity of artistic techniques and expressive possibilities worldwide has become so great that there is no longer any opposition or competition between classical sculpture, possibly ecologically-inspired art, electronically produced works or completely different approaches. Today "multimedia" at art colleges and academies means working with all conceivable materials. In this increasingly diverse world, de Weryha's work, which is steeped in numerous traditions, still offers a self-contained picture and is also topical in relation to today's ecological debates, occupies a unique artistic position of outstanding quality.

Axel Feuß, April 2018

[25] http://freunde-de-weryha.de/

[26] Jan Stanisław Wojciechowski 2005, p. 6 f./10 f. (see further reading; text available online verfügbar on the website of the artist, polish, page 4/english, page 4)

[27] Jan de Weryha in an interview „Offenbarungen in Holz“ with Mariusz Knorowski 2006 (exhibition catalog Jan de Weryha-Wysoczański. Objawienia w drewnie, Orońsko 2006, page 3/7)

Further reading:

Jan de Weryha-Wysoczański. Holzobjekte 1999-2000, Ausstellungs-Katalog Ehemaliges Ausbesserungswerk der DB, Hamburg 2000. (Including: Helmut R. Leppien: Der Natur gleich nah und fern)

Strenges Holz. Heiner Szamida, Helga Weihs, Jan de Weryha, edited by Daniel Spanke, Ausstellungs-Katalog Kunsthalle Wilhelmshaven, Bielefeld 2004. (Including: Daniel Spanke: Anti-Rustika)

Jan Stanisław Wojciechowski: Jan de Weryha-Wysoczański. Epifanie natury w późno-nowoczesnym świecie. Oiekty z drewna Jana de Weryha-Wysoczańskiego/Epiphanies of nature in late-modern world. Jan de Weryha-Wysoczański’s objects in wood, Ausstellungs-Katalog Galeria Szyb Wilson, Katowice 2005

Jan de Weryha-Wysoczański. Drewno-archiwum, Ausstellungs-Katalog Patio Galeria Sztuki, Łódź 2005. (Including: Urszula Usakowska-Wolff: Archiwum bezczasowej czasowości/Archive of timeless time finiteness)

Mieczysław Szewczuk: Jan de Weryha-Wysoczański, in: Kwartalnik Rzeźby Orońsko, 1-2 (58-59), Orońsko 2005, pages 10-13

Jan de Weryha-Wysoczański. Objawienia w drewnie, Ausstellungs-Katalog Centrum Rzeźby Polskiej w Orońsku/Zentrum für polnische Skulptur, Orońsko 2006. (Including: Mariusz Knorowski: Objawienia w drewnie/Offenbarungen in Holz [Interview with the artist])

Maja Ruszkowska-Mazerant: Jak powstaje prywatne muzeum? – Rozmowa z Panem Janem de Weryha-Wysoczańskim – A discussion with Jan de Weryha-Wysoczański), in: Purpose – Przedsiębiorczość w kulturze, Nr. 42, March 2008; in English online: Workshop. How is a private museum set up? https://purpose.com.pl/en/archive/mag-nr_42/workshop/mag-how_is_a_private_museum_set_up.html

Dorota Grubba: Gdy postawa staje się formą/When an Approach Becomes a Form, in: EXIT. Nowa sztuka w polsce/New Art in Poland, Nr. 2 (66), Warschau 2006, pages 4112-4115

Magdalena Kościelniak: Jan de Weryha-Wysoczański – Archiwista Drewna, Magisterarbeit an der Kunstfakultät der Universität Rzeszów, 2008 (a German translation can be found on the artist's website)

Tabularium. Jan de Weryha-Wysoczański, Ausstellungs-Katalog Gdańska Galeria Miejska, Gdańsk 2009. Including: Grażyna Tomaszewska-Sobko: W okowach percepcji/In den Fesseln der Wahrnehmung; Katarzyna Rogacka-Michels: Szorstkie drewno/Rough Wood

Aleksandra Warchoł: Wystawa jako dzieło sztuki, na podstawie twórczości Jana de Weryhy-Wysoczańskiego (English: The Exhibition as a work of art, using the works of Jan de Weryha-Wysoczański), a Master's dissertation at the Faculty of Art of the Technological University in Radom/Politechnika Radomska im. Kazimierza Pułaskiego, Radom 2011 (including an interview with the artist. (There is a German translation on the artist's website)

Maryla Popowicz-Bereś: Jan de Weryha-Wysoczański. Monografia artysty, a Master's dissertation at the Department of Pictorial Arts in the University of Rzeszów, 2014. (There is a German translation on the artist's website)

Online:

The artist's website with an overview of his work, exhibitions, biography and literature: http://www.de-weryha-art.de/

Sława Ratajczak: Arboretum duszy mojej – o znanym w Niemczech rzeźbiarzu polskim Janie de Weryha-Wysoczańskim (2011), on Polonia Viva, http://poloniaviva.eu/index.php/pl/?option=com_content&view=article&id=125:arboretum-duszy-mojej-o-znanym-w-niemczech-rzebiarzu-polskim-janie-de-weryha-wysoczaskim&catid=9:artyku&Itemid=4

Helga König talking with the artist Jan de Weryha-Wysoczanski (2015), on the interview page Helga König und Peter J. König. Buch, Kultur und Lifestyle, http://interviews-mit-autoren.blogspot.de/2015/03/helga-konig-im-gesprach-mit-dem.html