Józef Szajna in Maczków

Mediathek Sorted

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Józef Szajna - Hörspiel von "COSMO Radio po polsku" auf Deutsch

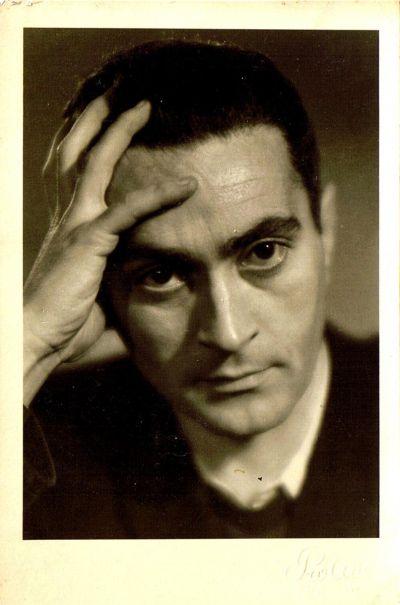

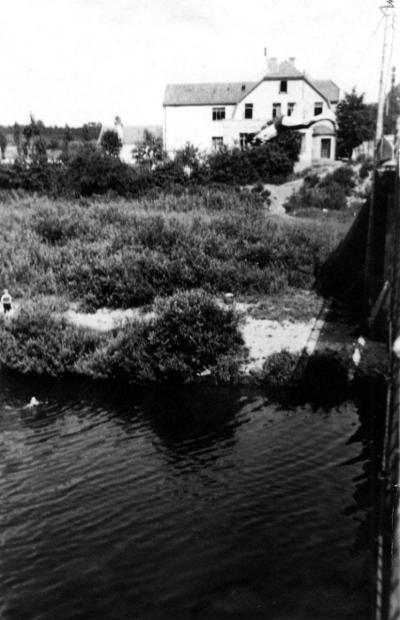

Condemned to life. Józef Szajna in Maczków on the Ems: 1945-1947

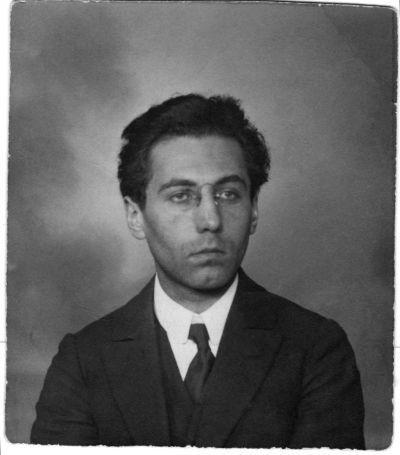

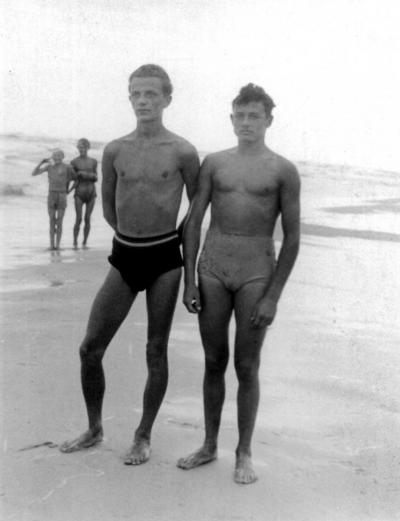

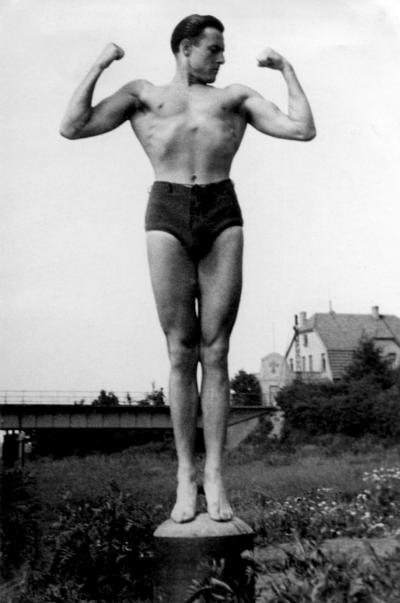

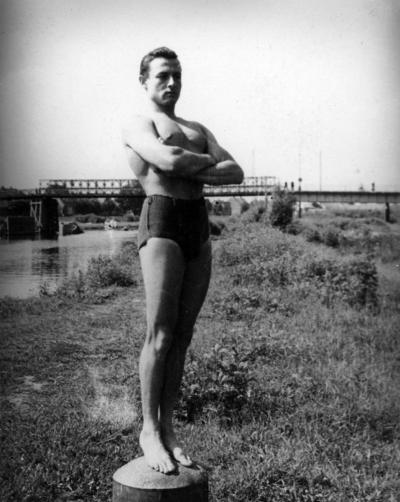

Józef Szajna was born on 13th March 1922 in Rzeszów, East Poland. At that time Poland had just been restored as an independent country by the Treaty of Versailles after being wiped off the map of Europe for over 120 years. When the black clouds of Nazi tyranny reached their peak with the invasion of Poland on 1st September 1939 that marked the beginning of the Second World War, Szajna was just seventeen. In 2015 his son Łukasz wrote that “People should know that my father had competed in the Polish swimming Championships before the outbreak of the war. He was the Polish junior champion in trampolining, and the Polish runner-up in long distance swimming (at the time this was 400 m)”. Alongside his career as an athlete, Szajna was active in the traditionally patriotic Polish Boy Scout movement. When, in the middle of September 1939, it was already clear that the swiftly advancing German troops could not be halted despite the fierce resistance of the Poles, and the invasion of the Red Army from the East would seal the defeat of Poland, Szajna signed up as a member of the military Boy Scout organisation, “Szare szeregi” (Grey Formations), took an active part in building up a conspiratorial resistance movement and participated in a number of sabotage attempts under the codename “Esjot 25”.

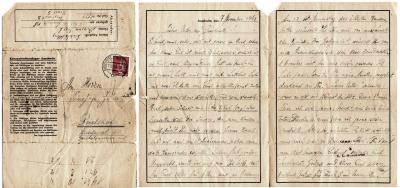

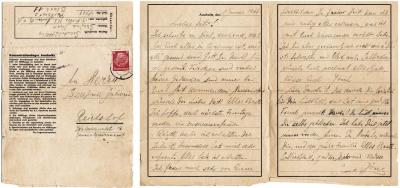

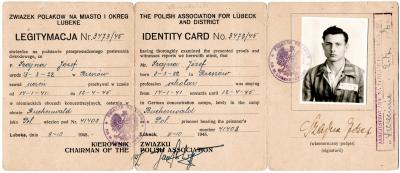

After he realised that he was likely to be imprisoned he decided to flee to Hungary to join up with Polish units in exile. But several attempts to flee over the “Green Border” were all foiled. He was interned in Slovakia and handed over to the Germans on his nineteenth birthday, the 13th March 1941, in the area of the so-called “General Government” that the Germans had set up occupied Polish areas. He was subsequently imprisoned in several places including the Gestapo jail in Muszyna and, after being classified as a political prisoner, was held under inhuman conditions in Tarnów. After only four months his weight had decreased from 78 to 46 kilograms. On 25th July 1941 he was transferred to the concentration camp in Auschwitz where he suffered the worst experiences of his life. He later wrote of his time there: “I now weigh 43 kilos, have dysentery and am known as number 18729”.

After a failed attempt to escape he was sentenced to death in Auschwitz in 1943. For the first stage of this punishment, which was clearly intended as a deterrent, he was shut up in a so-called “standing cell”, a 90 x 90 centimetre windowless room in which it was impossible to sleep. Most prisoners did not survive this torture and were spared having to face the firing squad. Szajna survived for two weeks. Shortly before he was due to be executed he learnt that his death penalty had been suspended. Physically emaciated and psychically blunted he was then detailed to serve in a number of different labour battalions. He was a witness to the most barbaric death machine in the history of humanity and, given his daily confrontation with death, increasingly suffered from the survival complex that was later often known as being “condemned to life”.

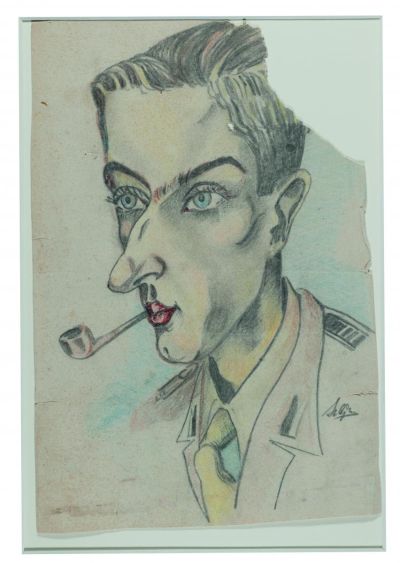

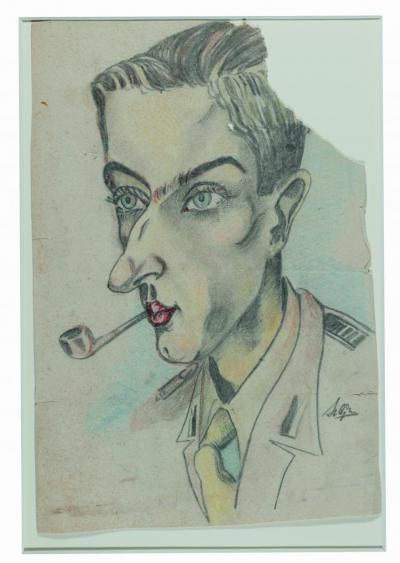

In winter 1944 he was transferred to the concentration camp in Buchenwald, and taken to the external camp in Schönebeck near Magdeburg. Here he made his first wall paintings using the burnt ends of matches. On 15th April 1945 he managed to flee from a death march ordered by the camp commanders.

Immediately after the liberation he considered returning to Poland, but before that he wanted to complete his A-levels. Such an enterprise seemed impossible in his home country that had been destroyed. When he learned of the existence of a town called Maczków on the Ems, a Polish enclave in the north-east of Germany, he decided to make his way there.

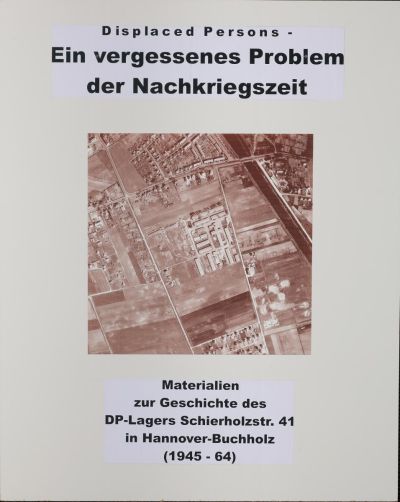

Here he stayed for over two years, and here he was able to experience the one thing that the majority of Poles in Germany yearned for after the Second World War: the breath of freedom, a feeling that was only too understandable after the years of deprivation, cruelty and absurdities of the war that the Germans had started. Perhaps also because it was impossible to foresee a free Poland in the post-war European order. The consequences of this new order were all too clear for the Polish forced labourers, prisoners of war, concentration camp prisoners and members of the Allied combat units, when the country was divided into three parts. There was no longer any free homeland to return to and the accompanying dilemma of whether to return or remain in emigration inevitably led to inner conflicts.

Given these preconditions it was a small miracle that word quickly spread amongst the Poles in Germany about Haren on the Ems. Indeed it only took a few months for the town to take on the character of a legend. In April 1945 the British Allied authorities decided to evacuate the town entirely and hand it over to Poles who were stranded in the region. The 3,000 original inhabitants were given only a short time to pack their belongings before most of them were housed in farmhouses in the surrounding countryside. Around 5,000 Poles then moved into their houses and apartments. The majority of them were soldiers – both men and women – who had met up under dramatic circumstances in the nearby prisoner of war camp in Oberlangen. More than 1,700 people who had participated in the Warsaw uprising in August/September 1944 had been held prisoners there as ex-soldiers and officers. The majority of these were girls and women who had fought against the Germans by working in the areas of communication and nursing. Many of them had falsified their birth dates in order to be treated as adults and enable them to take part in the uprising. After its brutal repression, the mass execution of the rebels and the civilian population, along with the hitherto unheard of annihilation of the Polish capital, they were deported to the Emsland. The forged birth dates proved to be a blessing, for the Germans did not recognise minors as combatants, and would otherwise have sent them directly to the concentration camps.

There has seldom been such an irony of history. It was none other than Poles, led by the first tank division of the Allied combat units under General Stanisław Maczek, who liberated the camp in Oberlangen. The amazement and joy must have been extraordinarily dramatic when Polish soldiers completely unexpectedly met up with Polish girls and young women to celebrate the end of the war. Just a few months later a mass wedding featuring over eighty couples took place; and shortly afterwards a huge number of children were born. The town was given the Polish name of Maczków in honour of General Maczek, along with a completely Polish administration and infrastructure. Even the street names were changed into Polish. There were kindergartens, schools, a grammar school where Szajna completed his A-levels, two theatres, Polish libraries and periodicals. Craft workers catered for people’s everyday needs. There was a lively social life. People seemed to be happy there, and for a short time Maczków seemed to be a Polish paradise abroad. Hence it was a magnet for other Poles living in Germany.

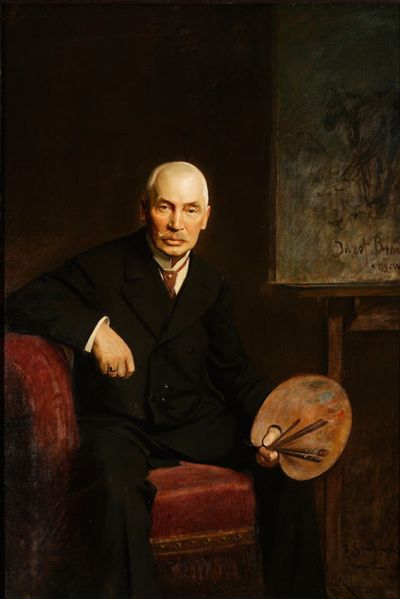

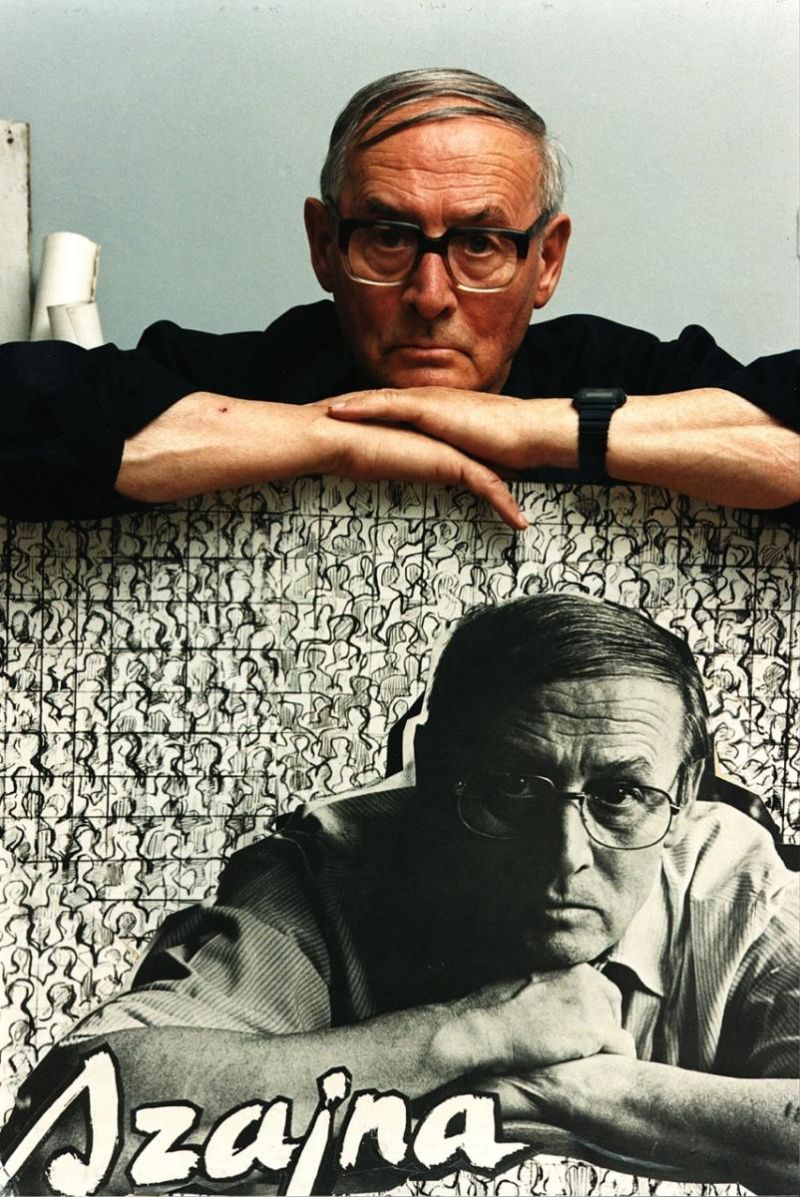

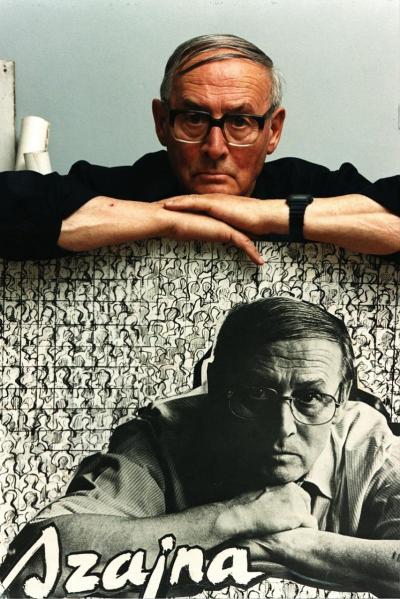

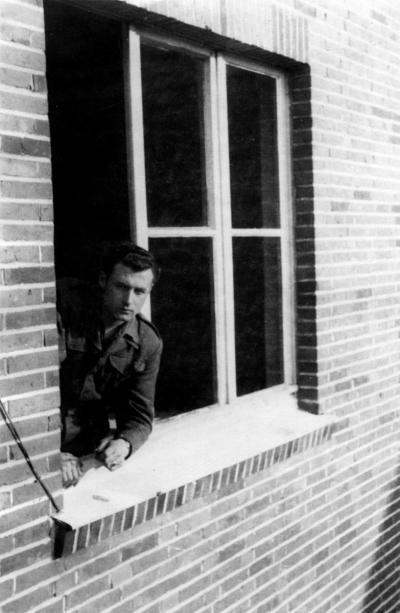

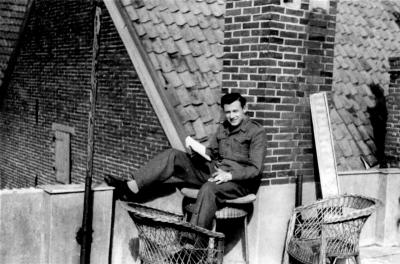

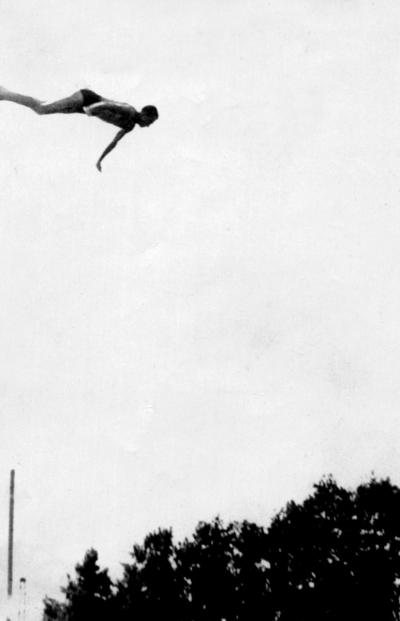

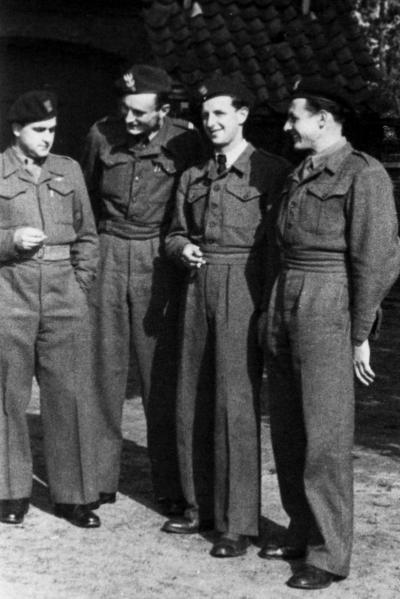

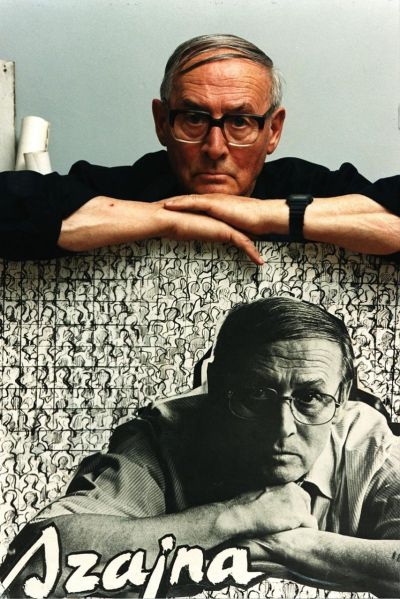

Józef Szajna too had the feeling that he was living in a completely different atmosphere, which he later described as his reincarnation. It took no longer than one year in “Little Poland” on the Ems for him to regain his old athletic stature: and if we look at photographs from his time on the Ems he was clearly proud of this. The temporary Polish paradise in the land of the criminals was surely the place where he found his life’s mission that was based on the survival complex that he never overcame. “Now that I have survived under such unbelievable conditions”, he said later in a huge number of conversations in interviews, “I feel I have to pass on my experiences as a warning”. To do this he chose the means of pictorial art and theatre. As early as 1947 he began to study at the Academy of Art in Kraków, and quickly became one of the best-known modern artists and theatre makers in Poland. He was mentioned in the same breath as Jerzy Grotowski and Tadeusz Kantor, but never really got on personally with the latter.

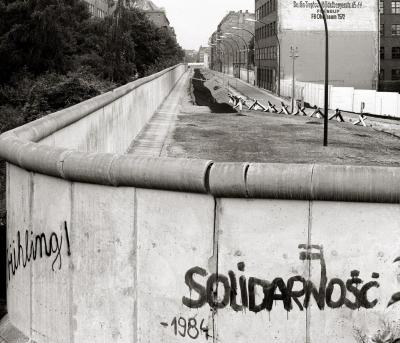

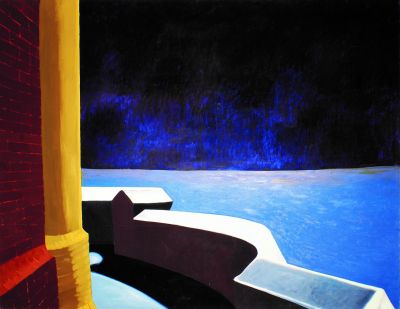

By the end of the 1970s his work had attracted international renown. His paintings, plays and installations were to be seen everywhere, also in Germany. From today’s perspective it is remarkable that Szajna’s art never spoke directly about death but concentrated on “turning towards the future, to concepts linked with the paradigms of the modern that had been interrupted by the war, and which could wipe out the memories of recent dark experiences”. His work was always opposed to simplification and the schematisation of the culprits. Hence, despite the fact that he could never rid himself of his survival trauma for good, he devoted his efforts to portraying people and their living conditions in the post-war world. Józef Szajna died in Warsaw on 24th June 2008.

Jacek Barski, October 2016

For more information about Józef Szajna and his work (polisch):